Background and Objectives: An increased focus on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ+) care in graduate medical education is needed to address health disparities in this patient population. This study assessed practice confidence and practice intentions of residents who rotated through an LGBTQ+ clinic during their residency.

Methods: Residents completed three to eight half-day sessions in a dedicated LGBTQ+ clinic focusing on primary care, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and gender-affirming care from 2019 to 2022. Prior to this clinical experience, they were provided background reading materials, care guidelines, and clinical cases. Residents were electronically surveyed at two time points after completing this clinical experience to retrospectively assess their pre-and postcurricular confidence.

Results: Seventeen out of 18 (94%) residents who completed the curricular experience responded to the initial survey, which showed statistically significant differences between reported pre- and postcurricular confidence in providing primary care, PrEP, and gender affirmation care. Eight-eight percent of residents reported that they planned to or have already incorporated this care into their practice. In a follow-up survey 1 year later, 15 out of 18 (83%) responded, reporting consistent skills confidence. Seventy-one percent of participants reported currently providing LGBTQ+ care. We noted no statistical difference between the initial postconfidence survey and the follow-up survey.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated positive associations between a focused curricular experience in LGBTQ+ care and both confidence providing LGBTQ+ care and planned and actual postgraduation practice patterns.

Health disparities in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ+) individuals are staggering both in number and scope across mental and physical health.1-5 Although undergraduate medical education on LGBTQ+ care has increased, it is not enough to fully prepare physicians for practice, thus necessitating more exposure in graduate medical education.6,7 Despite repeated calls for formalized LGBTQ+ training for residents,6,8 few curricular models have been published.7,8 One family medicine residency developed a longitudinal curriculum with clinical learning opportunities and community collaboration but did not evaluate the effect of this experience on the confidence or future practice of residents.9

The goal of the current study was to evaluate a curriculum that educates residents on LGBTQ+ care in a dedicated LGBTQ+ clinic embedded within our primary teaching site. Our LGBTQ+ clinic occurred weekly in half-day sessions and was staffed with one resident and one attending preceptor (J.A. or S.H.). Up to seven patients were scheduled per session, including new and established. Patients were seen for LGBTQ+ care and primary care in an affirming environment. Access consisted of self-referral or formal referral by providers who did not provide LGBTQ+ care, both within and outside of our health system. Residents could choose to opt out of the educational experience. One resident opted out of medication management but participated in the remainder of the experience. This study assessed the reported postcurricular confidence and practice intentions of residents who rotated through the clinic.

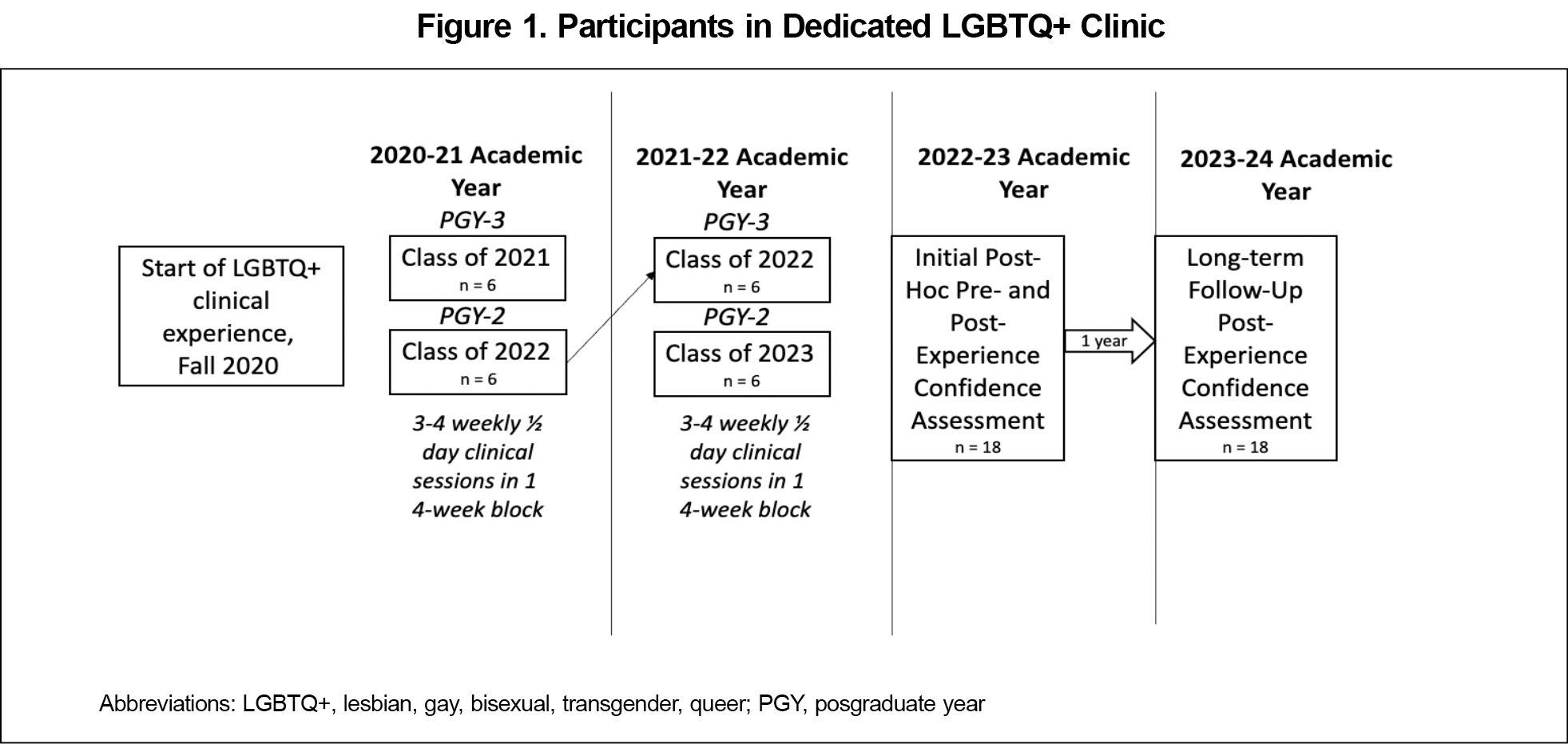

Family medicine residents in postgraduate years 2 (PGY2) and 3 (PGY3) participated in a dedicated LGBTQ+ clinic focused on primary care, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and gender-affirmation therapy from 2019 to 2022 (Figure 1). As part of the experience, residents were assigned background readings, including World Professional Association for Transgender Health10 and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention11 guidelines, and clinical cases on primary care, health maintenance, initiation of PrEP, and management of gender-affirming care. Preceptors reviewed this information with residents during their first clinical session. Electronic medical record (EMR) note templates were used to standardize visits and guide history-taking.

Study Design

We assessed residents’ perceived confidence with providing primary care, PrEP, and gender-affirming care for LGBTQ+ patients through an electronic survey administered at two time points following the curricular experience (Figure 1). When the initial survey was sent, residents had completed the experience between 2 weeks and 12 months prior. The initial survey asked residents (n=18) to recall their confidence in providing this care prior to and after the curricular experience.

The survey was anonymous and noncompulsory. Confidence was assessed on a 5-point scale from “not confident” to “extremely confident.” An inquiry into future intent to provide LBGTQ+ care was made in an open-ended format. The same survey was redistributed 1 year later to the same cohort (n=18) to assess their confidence in the same domains and to find out whether individuals were currently providing LGBTQ+ care.

Data Analysis

We used a paired-samples t test in Microsoft Excel to determine the statistical significance of changes in the residents’ reported confidence before and after the experience at both time points. We aggregated the open-ended responses into “yes” and “no” for clinical practice intentions, and we categorized justifications for these responses. This study was provided exempt status by the Prisma Health Institutional Review Board.

The initial survey response rate was 94% (17/18); the follow-up survey (distributed 1 year later) response rate was 83% (15/18).

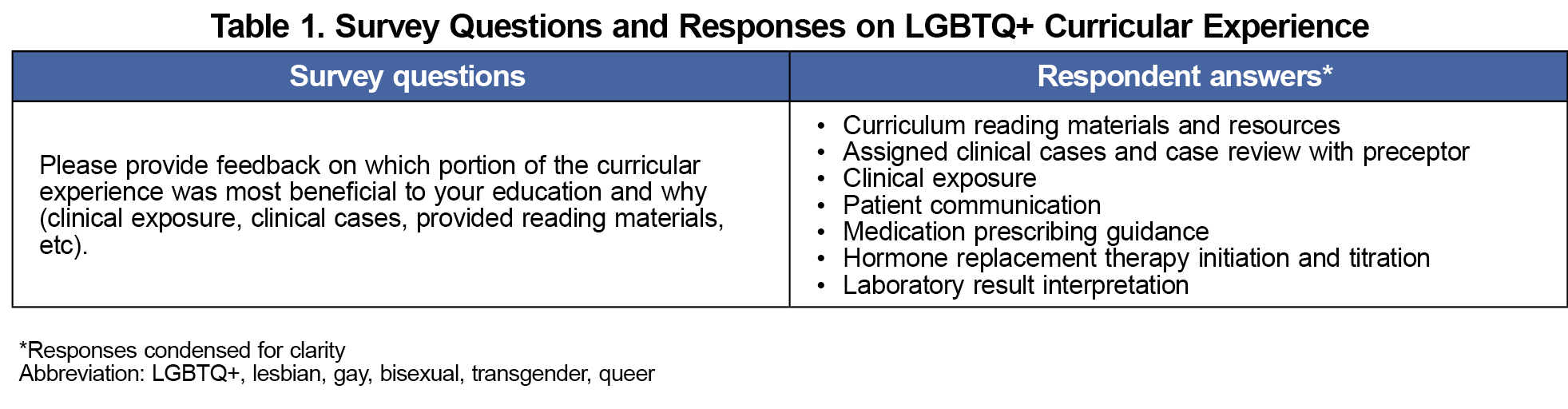

Prior to the experience, 53% of respondents reported minimal to no confidence in providing primary care and health maintenance to LGBTQ+ patients. Following exposure, 100% of respondents reported at least moderate confidence in providing primary care to this population (Figure 2). A paired t test indicated a statistically significant difference between reported prerotation confidence (M=2.35, SD=1.41) and postrotation confidence (M=3.65, SD=0.79; t[16]=6.285, P<.001). We found no statistically significant difference between the postrotation confidence reported in the initial survey and the confidence 1 year later (M=3.6, SD=4.33; t=2.13, P=.24).

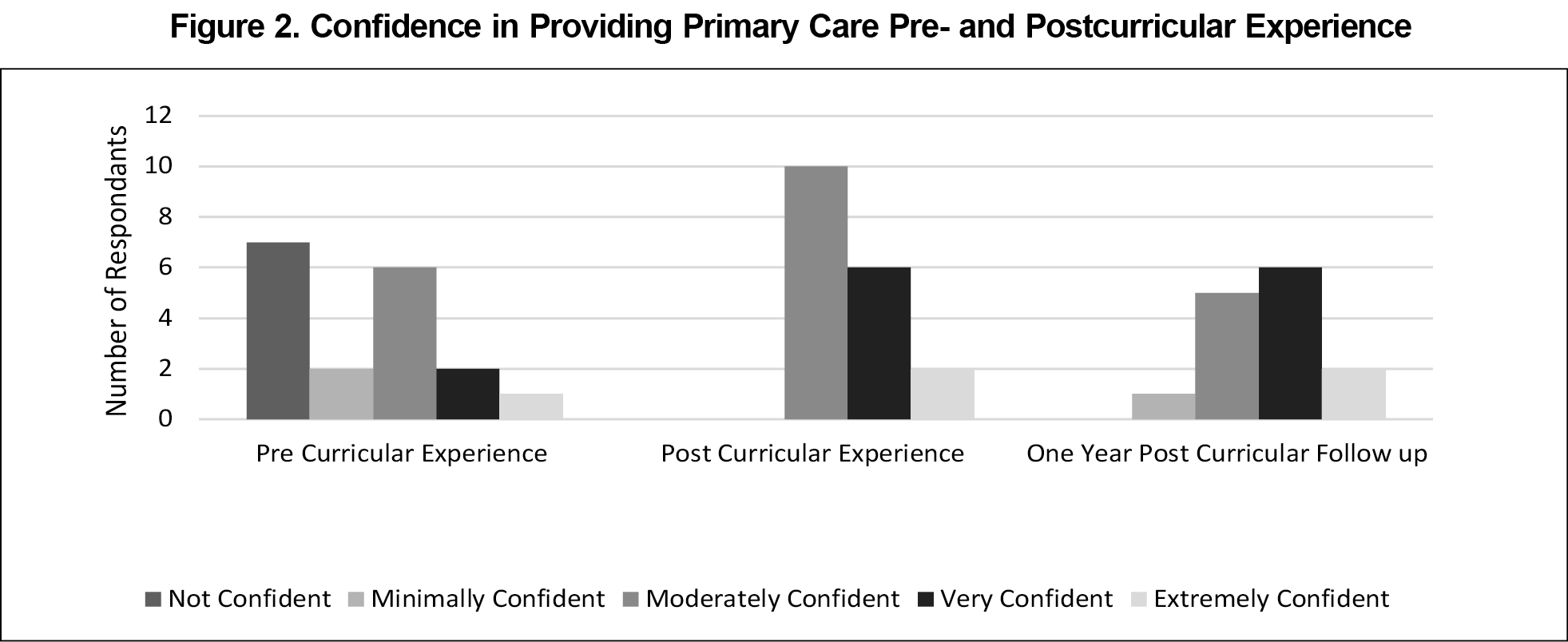

Prior to the rotation, 53% of respondents recalled having low to no confidence in indications for PrEP. Following clinical exposure, 82% of respondents reported moderate confidence in prescribing PrEP (Figure 3). A paired t test indicated a statistically significant difference between post hoc prerotation confidence (M=2.00, SD=1.06) and initial postrotation confidence (M=3.62, SD=0.72; t[16]=6.68, P<.001). We found no statistically significant difference between postrotation confidence reported in the initial survey and confidence 1 year later (M=1.8, SD=2.5; t=2.24, P=.06).

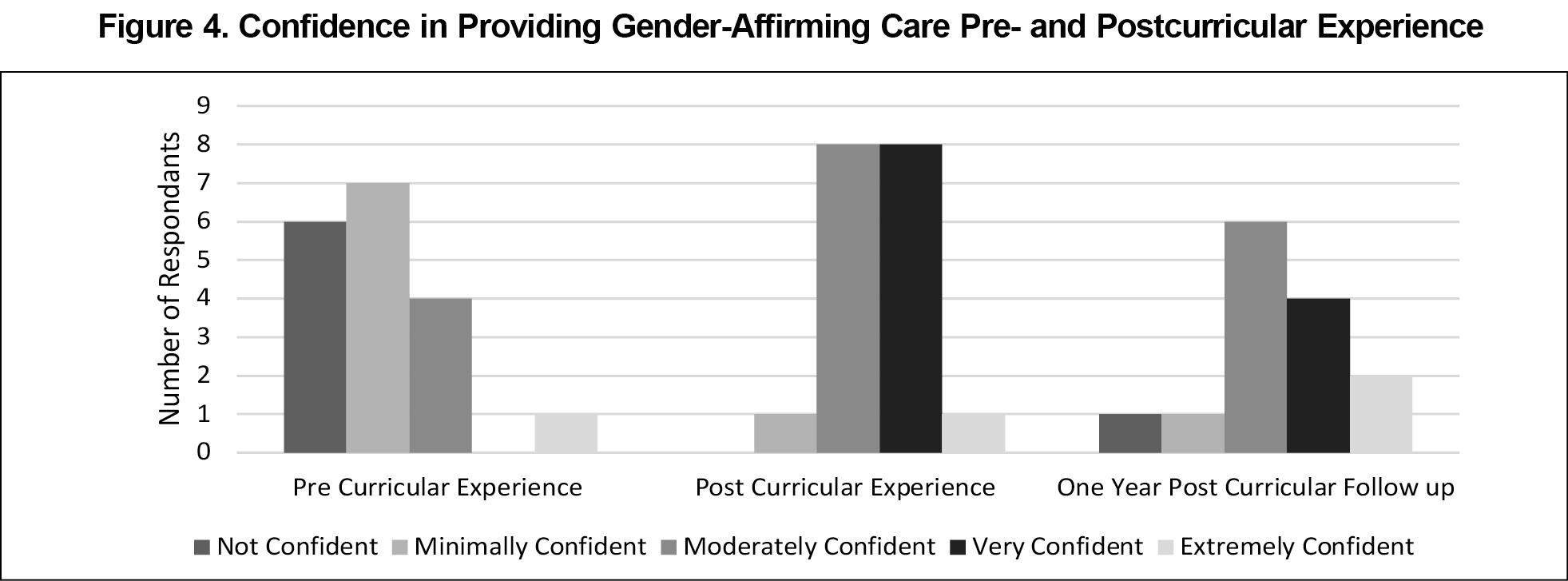

Prior to this experience, 76% of respondents recalled having minimal to no confidence in providing gender-affirming therapy. After the experience, 94% of respondents reported moderate confidence in providing gender-affirming care (Figure 4). A paired t test indicated a statistically significant difference between post hoc prerotation confidence (M=2.29, SD=1.05) and initial postrotation confidence (M=3.41, SD=1.0; t[16]=4.96, P<.001). We found no statistically significant difference between postrotation confidence reported in the initial survey and confidence 1 year later (M=2.2, SD=4.03; t=1.12, P=.16).

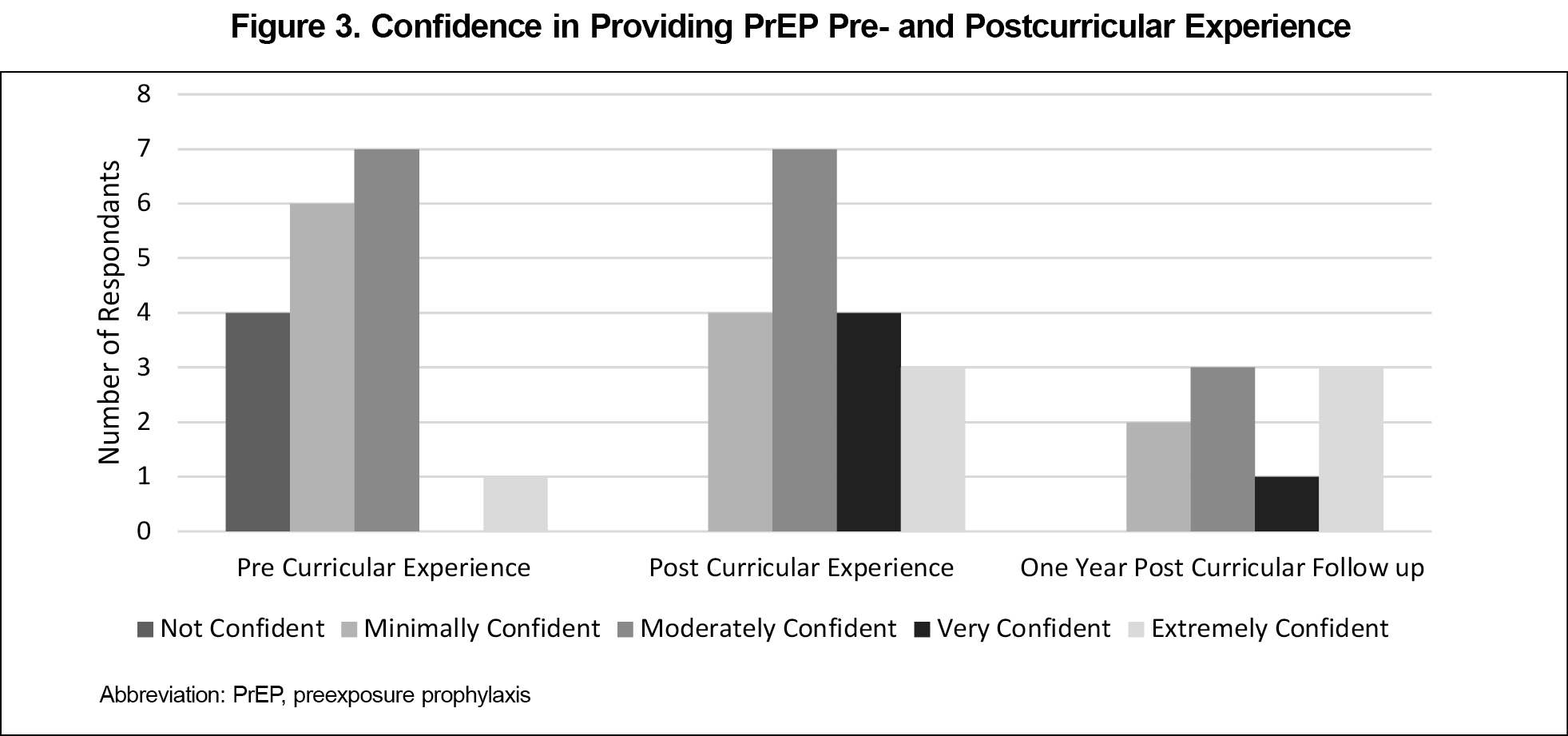

Following the curricular experience, 76% of respondents reported feeling that they had sufficient clinical exposure with this population. The helpfulness of clinical exposure and knowledge of guidelines and reference materials were highlighted most often in the open-ended responses (Table 1).

In the initial survey, 88% reported practicing or planning to practice in at least one of the three domains, while 12% reported no plans to provide specific care for this population. In the follow-up survey 1 year later, 71% of respondents reported currently providing LGBTQ+ care.

Lack of training has been noted as a barrier to providing care for LGBTQ+ patients.12 In this study, a relatively small educational intervention enabled a majority of residents to feel confident to provide LGBTQ+ health care in the future and to maintain this confidence over the course of a year. This finding suggests that the actual education gap is potentially smaller than many clinicians may perceive it to be.

This study helped to meet a demonstrated gap in the literature on models for residents in graduate medical education to gain the knowledge and skills needed to practice competent LGBTQ+ health care. Our findings suggest that more residencies implementing similar programs would likely better prepare residents to meet the health care needs of LGBTQ+ individuals nationwide.

Limitations

The most significant limitation of this study was the lack of a true preassessment; our post hoc assessment of recalled pre-experience confidence is subject to recall bias. Additionally, our survey measured perceived confidence rather than observed clinical competency. Our survey also did not measure the number of sessions each resident participated in; thus, we were unable to correlate perceived confidence with the amount of clinical exposure the resident received. We did not assess how many residents completed the assigned prework prior to the curricular experience. We also did not ask whether residents intended to provide LGBTQ+ care prior to this curricular experience to investigate whether the experience changed any individual’s plans. Future studies should evaluate residents’ observable skills and competencies both before and after the experience. Although all residents who completed this experience were provided with the surveys and 94% responded initially and 83% at the 1-year follow-up, the sample size was still limited to 18 individuals.

This study suggests that, paired with educational materials, as few as three to eight clinic sessions in a dedicated clinic may result in a high level of resident confidence in LGBTQ+ care, with residents continuing to provide these services postgraduation. Residency programs implementing similar training models may develop the physician workforce to meet critical patient needs and bridge health disparities.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Molly Benedum, MD, for her tireless efforts to create a safe clinical space for residents and patients to receive care.

References

- Daniel H, Butkus R; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Health, Physicians. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health disparities: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(2):135-137. doi:10.7326/M14-2482

- Keuroghlian AS, Ard KL, Makadon HJ. Advancing health equity for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people through sexual health education and LGBT-affirming health care environments. Sex Health. 2017;14(1):119-122. doi:10.1071/SH16145

- Valentine SE, Shipherd JC. A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:24-38. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2018.03.003

- Matthews AK, Breen E, Kittiteerasack P, eds. Social Determinants of LGBT Cancer Health Inequities. Seminars in Oncology Nursing.Elsevier; 2018.

- Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. National Academies Press; 2011.

- Streed CG Jr, Hedian HF, Bertram A, Sisson SD. Assessment of internal medicine resident preparedness to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):893-898. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04855-5

- Player M, Jones A. Compulsory transgender health education: the time has come. Fam Med. 2020;52(6):395-397. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.647521

- Pregnall AM, Churchwell AL, Ehrenfeld JM. A call for LGBTQ content in graduate medical education program requirements. Acad Med. 2021;96(6):828-835. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003581

- Ruedas NG, Wall T, Wainwright C. Combating LGBTQ+ health disparities by instituting a family medicine curriculum. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2021;56(5):364-373. doi:10.1177/00912174211035206

- Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 2022;23(suppl 1):S1-S259. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

- Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm

- Shires DA, Stroumsa D, Jaffee KD, Woodford MR. Primary care clinicians’ willingness to care for transgender patients. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):555-558. doi:10.1370/afm.2298

There are no comments for this article.