Introduction: Health educators have had difficulty introducing health policy and public health training into an already intensive medical school curriculum. Although the COVID-19 pandemic may have changed perspectives on the importance of public health, it may not change educational approaches. Assessment of medical student opinions and perceptions of health policy and public health might influence the weight given to these topics in medical education.

Methods: We used a 39-item instrument to cross-sectionally survey medical students, to assess their perceptions of the value of public health and health policy within their professional education.

Results: One hundred two students completed the survey (13% response rate). Most students reported an interest in public health (94.1%) and health policy (92.2%). Although interested, most students lacked confidence in their knowledge of public health and health policy on both state (health policy 34.3% confident; public health 43.1%) and national (health policy 41.0%; public health 44.1%) levels. Most students perceived that their institution has not sufficiently prepared them to understand health policy (34% felt prepared) and most reported insufficient information to participate in policy discussions (30.3% sufficiently informed).

Conclusions: Medical students reported an interest in public health and health policy while also reporting a lack of confidence in their level of preparedness to understand and participate in these fields, thus demonstrating a need for increased public health and health policy education within medical school curricula.

Researchers have suggested that public health and health policy training is important and should be increased within health professional school programs.1-3 The COVID-19 pandemic has led some scholars to call for increased involvement of future physicians in public health.4 Public health and health policy are related, but distinct, concepts. Public health is defined by Rao et al as “[pertaining] to the health outcome and measurements thereof, and often includes interventions at [the] community-level to reduce risk and minimize cost of caring for chronic diseases that may be ameliorated by prevention.”4 Health policy is characterized by four domains, following Patel et al: “health care systems and principles, health care quality and safety, value and equity, and health politics and law.”5

Augmenting public health training has been identified as a curricular priority for medical education.1-3 A 2015 systematic review found widespread advocacy for greater public health education, but extensive analysis of the efficacy of such programs is lacking.3-5 A prepandemic (2018) multicenter survey of medical students found that while students generally felt interested in health policy, they did not feel confident about their own knowledge therein.6 Moreover, students’ perceptions of their knowledge of health policy could also be “the result of mainstream media coverage instead of curricular change or exposure to credible resources.”7

Given the changes medical education has undergone during the COVID-19 pandemic, an updated analysis of students’ opinions or assessment of their competencies and deficits would significantly improve the effectiveness of health policy curricula.8,9 Therefore, we used quantitative techniques to ascertain the opinions, attitudes, and beliefs of medical students related to training in national and state-level public health and health policy issues.

Participants

We included students who completed at least one semester and were currently enrolled in the spring 2022 semester at the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC) School of Medicine in Wichita, Salina, and Kansas City, Kansas, representing 829 eligible students. No students were excluded; all students received a link to participate by email. Data were collected via an electronic survey from January 2022 to February 2022.

Survey Development and Administration

We used a 39-question instrument developed from a previously-published survey examining medical student opinions of health advocacy and advocacy education within medical school.10 The survey was electronically distributed by the KUMC Office of Student Affairs, and responses were recorded using REDCap software.11,12

Statistical Analysis

We performed statistical analyses using R software, version 3.6.1; we used the Kruskal-Wallis test, a nonparametric test suitable for analysis of ordinal response variables,13 to analyze associations within participant responses. We controlled the false discovery rate of multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; 10 associative tests were specified a priori. The University of Kansas Medical Center institutional review board approved this study.

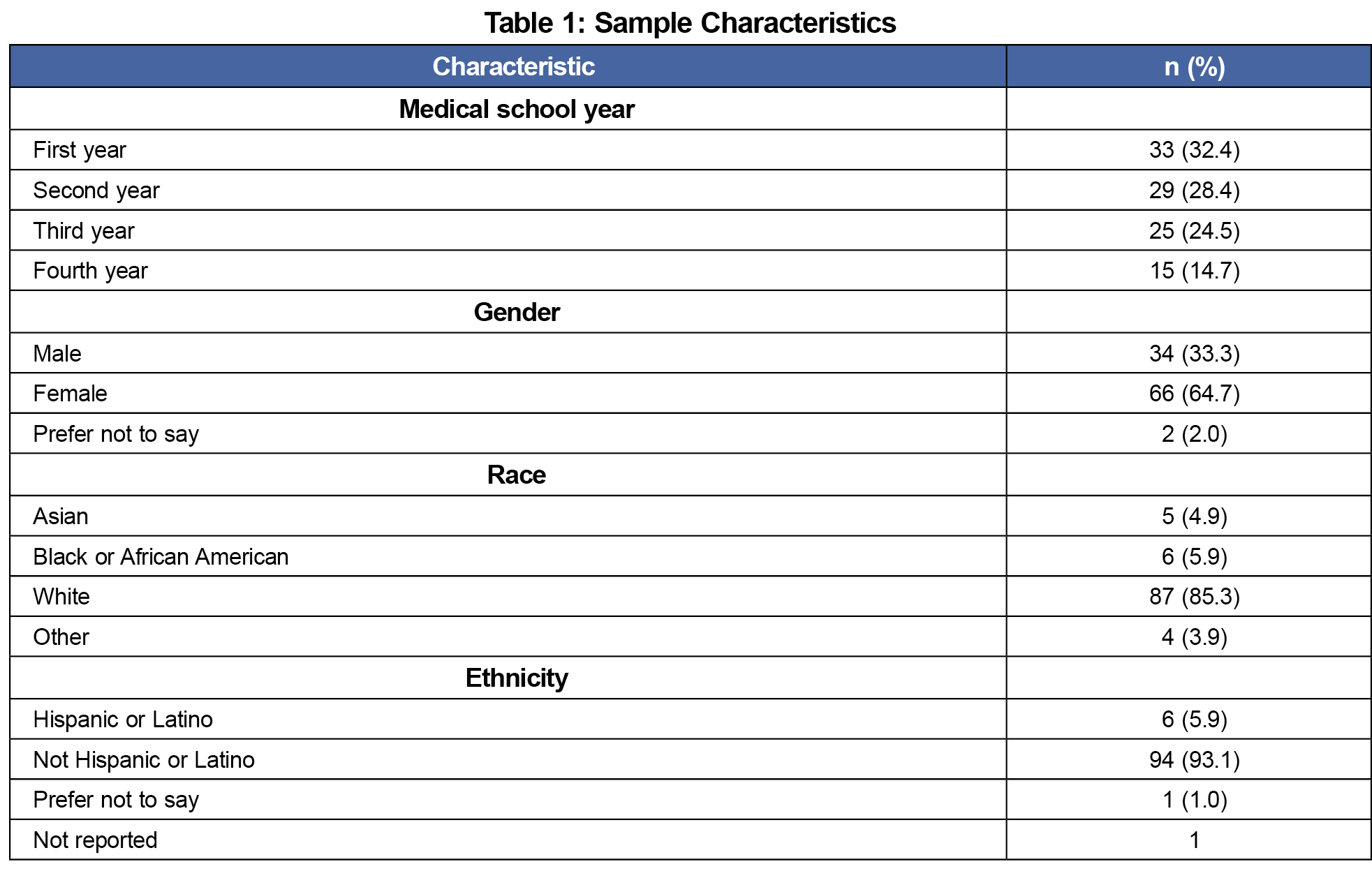

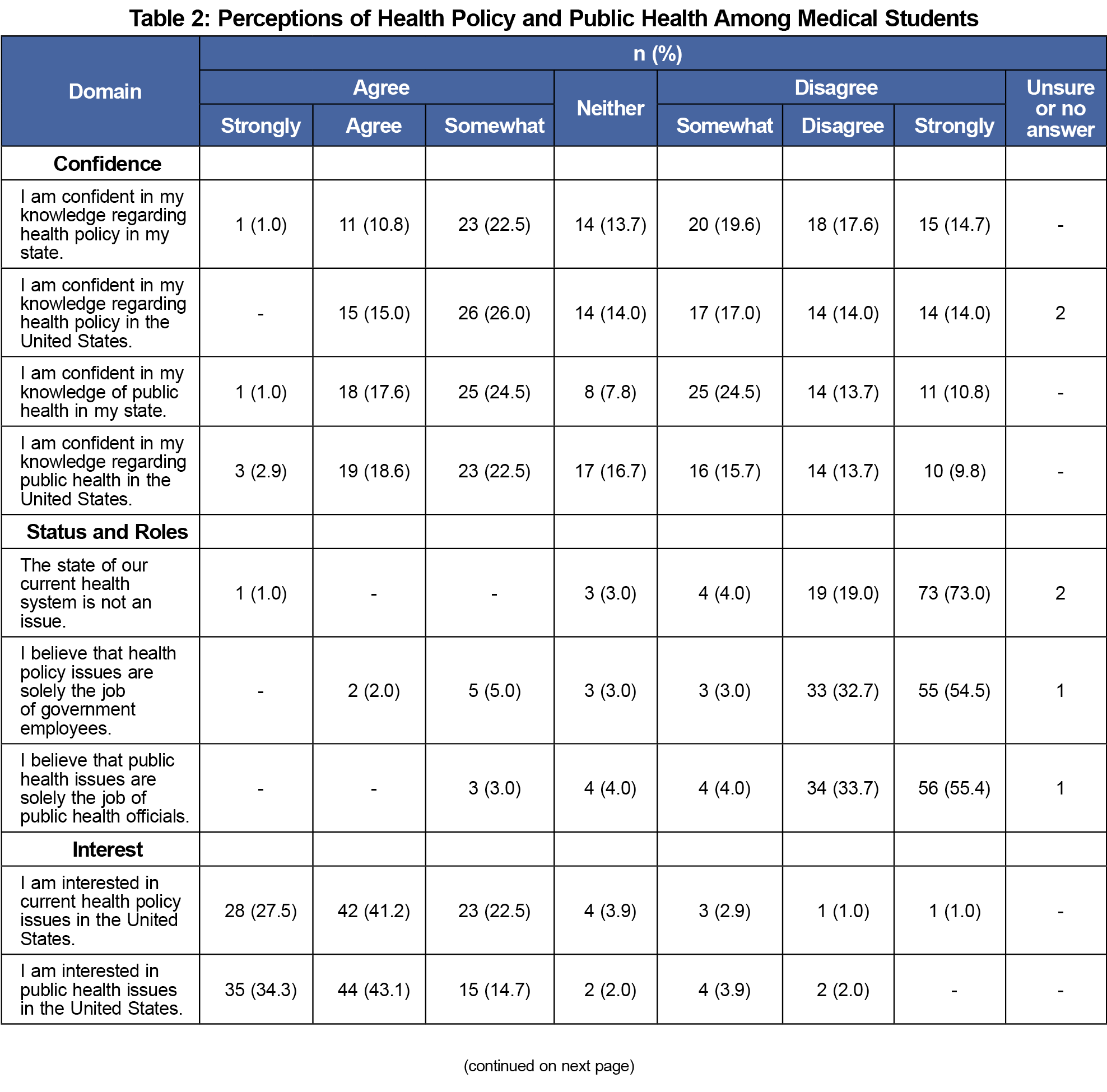

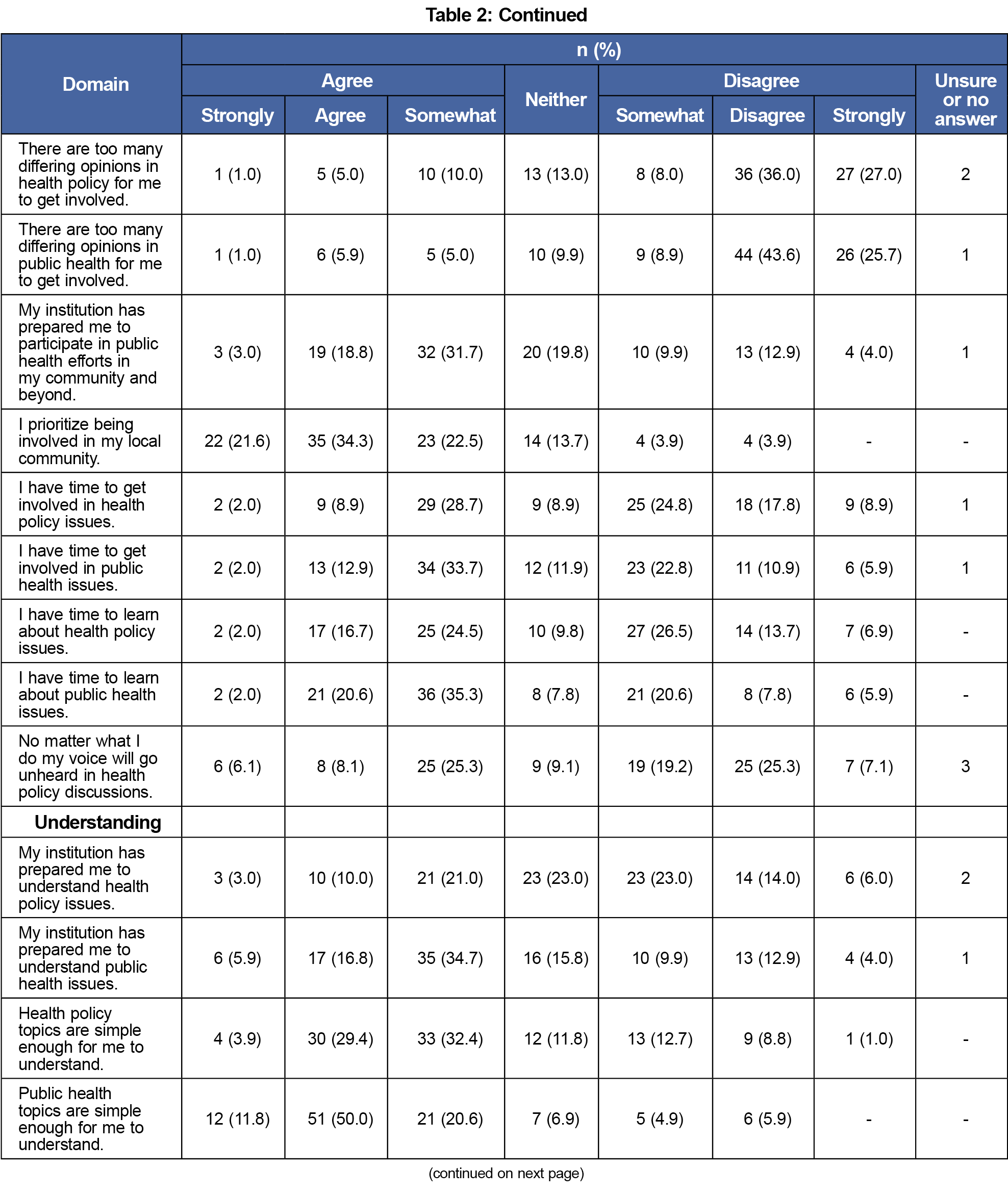

One hundred eight of 829 invited students responded to the survey (response rate=13%) including students from all years of training (Table 1). Students nearly universally expressed an interest in public health (94.1%) and health policy (92.2%; Table 2) Most students, however, were not confident in their knowledge of health policy or public health at either the national (health policy 41.0% confident; public health 44.1%) or state (health policy 34.3%; public health 43.1%) level. Indeed, most students felt they did not have enough information to get involved in health policy discussions (69.8% lack information).

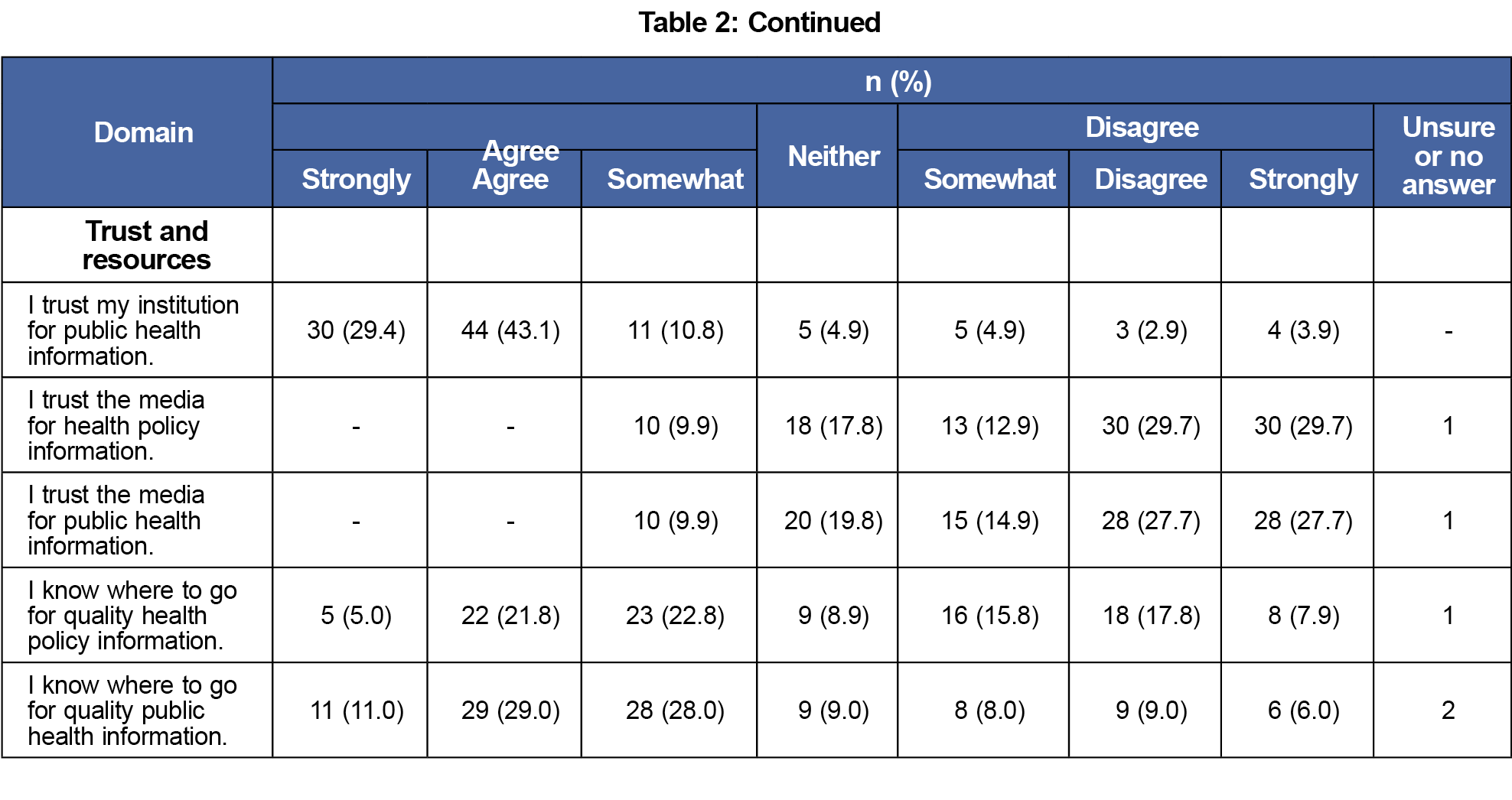

Regarding sources of information about public health and health policy topics, students largely trusted their medical school (public health 83.3% trust; health policy 79.4%) but distrusted the media (public health 9.9%; health policy 9.9%) While most students felt that their institution had prepared them to understand public health issues (57.4% felt prepared), they did not feel that their institution has prepared them to understand health policy issues (34% felt prepared).

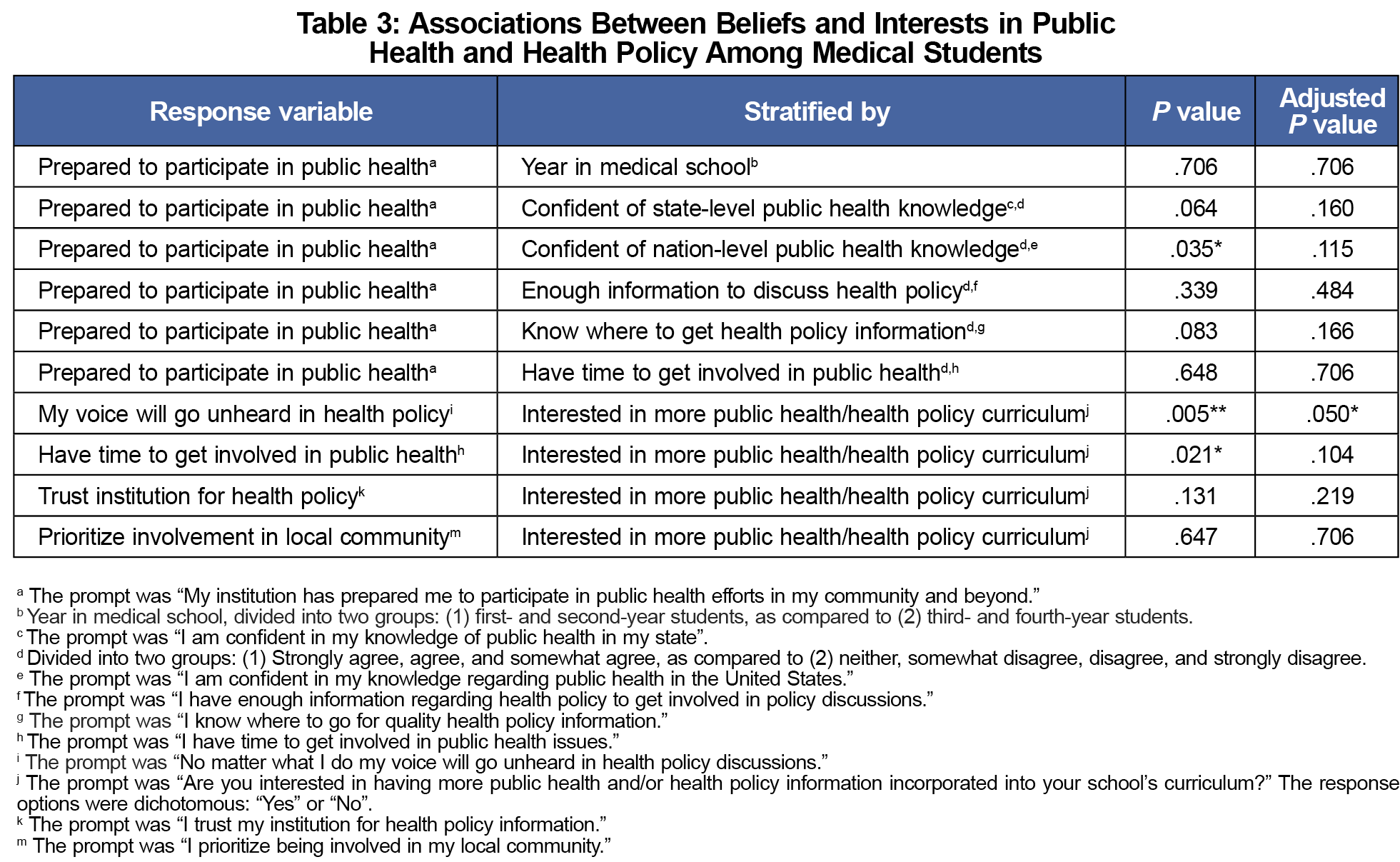

We found two associations related to greater interest in health policy curriculum: (1) a negative association with belief that their voice will go unheard in health policy discussions (P=.005; adj. P=.050), and (2) a positive association with perceived time of the student to get involved with public health issues (P=.021; adj. P=.104). We also found a positive association between perception that medical school has prepared the student to participate in public health efforts and confidence in public health knowledge at the national (P=.035; adj. P=.115) but not state (P=.064; adj. P=.115) level (Table 3). The strength of these associations was attenuated under correction for multiple hypothesis testing. These results should therefore be considered hypothesis-generating rather than definitive confirmations of these associations.

Medical students in this study expressed interest in public health and health policy at both the state and national levels. They lack confidence, however, in their knowledge of public health and health policy, and perceive they have insufficient information to be able to participate in health policy discussions. Most students perceived their medical school had not prepared them adequately to understand health policy issues but reported high confidence in their medical institution as sources of information.

Our results are concordant with the call for an increased focus on public health and health policy within medical school curricula.1-3 Large-scale studies of medical students should be conducted to gather the necessary data for curriculum development and determine if regional trends exist. Prospective analyses are also needed to assure that curricula in public health and health policy result in sustained professional involvement in public health and health policy.

This study has limitations. First, it was conducted within a single institution; caution is indicated when generalizing these results to other institutions. Second, our sample size is modest with a similarly modest response rate, which increases the possibility of nonresponse bias. Students in earlier stages of training and women are likely overrepresented in our data. Students with strong opinions about health policy and public health may also have been more likely to respond to the survey. We were prohibited by institutional policy from sending multiple survey reminders or taking other measures to increase response rates. Third, we performed multiple associative analyses; although these were specified a priori, these results should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than definitive.

We echo calls from public health policy experts to focus medical education resources on public health and health policy in pre- and postdoctoral medical education. Further multicenter analyses, and those analyzing other levels of medical learners, are needed to guide curricular development.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Dixon, Ayres, Leonard, Greiner

Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: Dixon, Ayres, Leonard, Parente

Drafting of the manuscript: Dixon, Ayres, Leonard, Parente

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Dixon, Ayres, Leonard, Greiner, Parente

Statistical analysis: Parente

Administrative, technical, or material support: Parente, Greiner

Study supervision: Greiner, Parente

Presentations

This study was previously presented at the following venues:

- Kansas Academy of Family Physicians Fam Med Forward 2022; June 2, 2022; Kansas City, MO

- American Medical Association 2022 Group on Student Affairs, Careers in Medicine, Organization of Student Representatives National Meeting; April 7, 2022; Denver, CO

- American Medical Association Region 3 Physicians of the Future Summit; February 5, 2022 (virtual)

References

- Allan J, Barwick TA, Cashman S, et al. Clinical prevention and population health: curriculum framework for health professions. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(5):471-476. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(04)00206-5

- Clancy TE, Fiks AG, Gelfand JM, et al. A call for health policy education in the medical school curriculum. JAMA. 1995;274(13):1084-1085. doi:10.1001/jama.274.13.1084

- Heiman HJ, Smith LL, McKool M, Mitchell DN, Roth Bayer C. Health policy training: a review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;13(1):ijerph13010020. doi:10.3390/ijerph13010020

- Rao R, Hawkins M, Ulrich T, Gatlin G, Mabry G, Mishra C. The evolving role of public health in medical education. Front Public Health. 2020;8:251. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00251

- Patel MS, Davis MM, Lypson ML. Advancing medical education by teaching health policy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):695-697. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1009202

- Theophanous C, Peters P, O’Brien P, Cousineau MR. What do medical students think about health-care policy education? Educ Health (Abingdon). 2018;31(1):54-55. doi:10.4103/1357-6283.239049

- Kagan CM, Armstrong GW. Health policy in medical education: a renewed look at a timely and achievable imperative. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):838. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000747

- Ferrel MN, Ryan JJ. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7492. doi:10.7759/cureus.7492

- Torda AJ, Velan G, Perkovic V. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education. Med J Aust. 2020;213(7):334-334.e1. doi:10.5694/mja2.50762

- Aliani R, Dreiling A, Sanchez J, Price J, Dierks MK, Stoltzfus K. Health Advocacy and Training Perceptions: a Comparison of Medical Student Opinions. Med Sci Educ. 2021 Aug 24;31(6):1951-1956. doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01394-9

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Guo S, Zhong S, Zhang A. Privacy-preserving Kruskal-Wallis test. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2013;112(1):135-145. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.05.023

There are no comments for this article.