Introduction: Professionalism as a competency in medical education has been defined in multiple ways. Irby and Hamstra offered three frameworks of professionalism in medical education. This study examines medical students’ definitions of professionalism to assess whether they align with these frameworks.

Methods: We administered an open-ended questionnaire to 92 medical students at a single university in the United States. We conducted thematic coding of responses and calculated code frequencies.

Results: The response rate was 54%. There were no observable differences between the responses of students in clinical versus preclinical training phases. The majority of comments (84%) reflected aspects of multiple frameworks from Irby and Hamstra and three emergent themes were identified. Most respondents (96%) cited aspects of the behavior-based framework. Most students’ (66%) responses also aligned with the virtue-based framework. Emergent themes were “hierarchical nature of medicine,” “academic environment/hidden curriculum,” and “service and advocacy.” “Service and advocacy” can be viewed as contexts for Irby and Hamstra’s identity formation framework, but references did not align with the full definition.

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that students view professionalism through multiple frameworks and indicate a predominance of the behavior-based framework. Experiences with organizational culture and values may be important in students’ definitions of professionalism.

Professionalism as a competency in medical education2-5 has been defined in multiple ways.1,6-9 Irby and Hamstra offered three frameworks: (a) virtue-based professionalism, focusing on moral character; (b) behavior-based professionalism, measured in competencies and observable behaviors; and (c) professional identity formation, integrating individual identity into community values.10

Design Thinking is gaining traction in education13 asserting that alignment between stakeholder definitions and user experiences is key. Misaligned views of medical student professionalism can be detrimental; Stubbing, et al found students felt pressured to “epitomize the values and behaviors of a doctor from the onset of medical school,” despite lacking prerequisite competencies, an incongruity with potential patient safety implications.14

This exploratory qualitative study examined medical students’ definitions of professionalism to assess whether they align with existing frameworks.

Medical students (N=92) participating in family medicine electives at one US university were invited to complete an open-ended questionnaire asking the student’s year in the MD program and the question, “What is medical student professionalism?” The site’s institutional review board granted the study an exemption from review.

Data were collected in 2021, using REDCap software,15 and downloaded to Microsoft Excel for thematic analysis.16 Two authors checked data. We used a deductive approach, drawing upon Irby and Hamstra’s frameworks, and we completed a holistic reading of all responses before coding 25% together to ensure calibration. Coding continued line by line, and the process endured iteratively with authors coding independently and meeting to ensure 100% agreement.

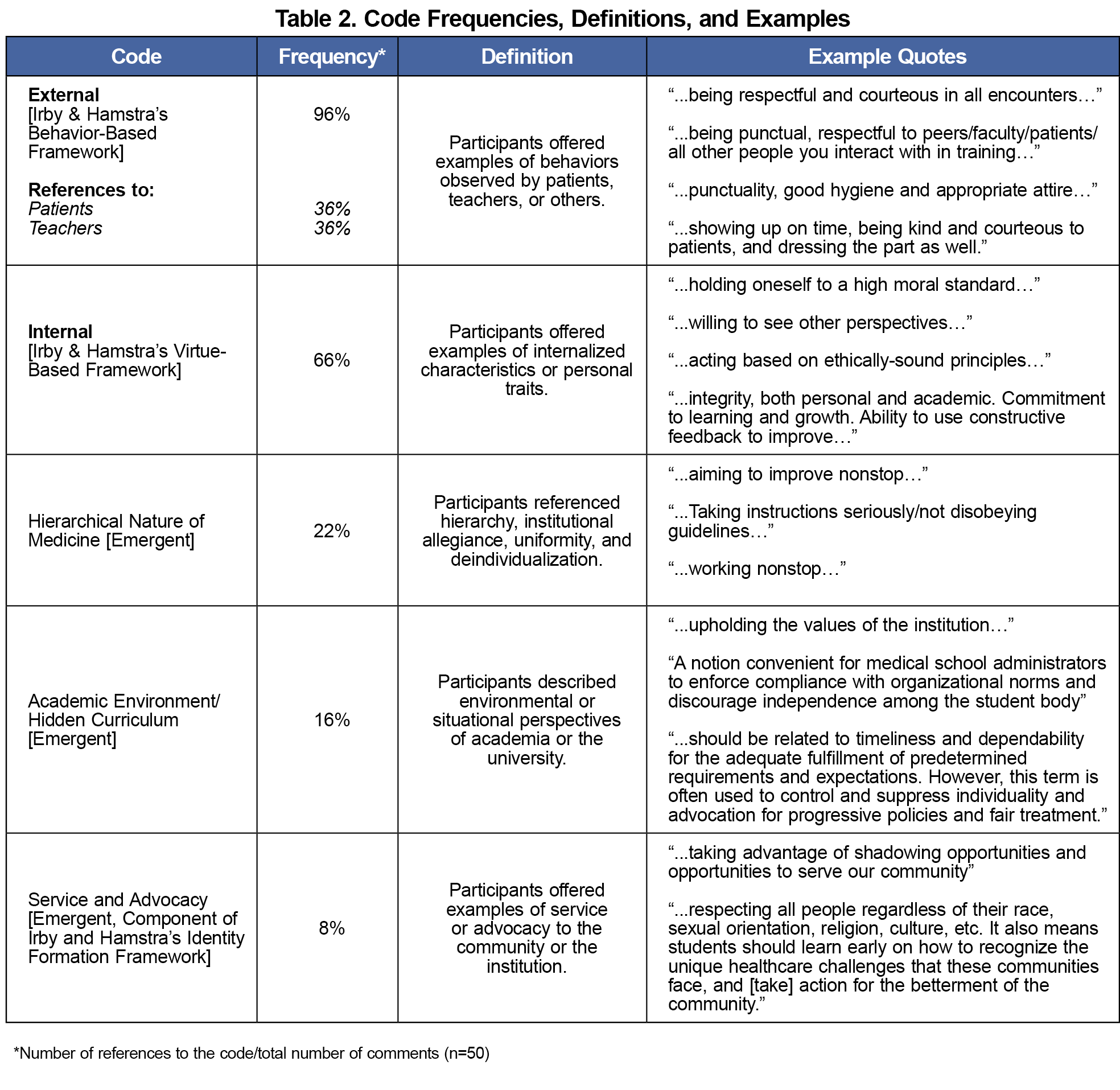

We calculated code frequencies using the following formula: number of references to the code/total number of comments (n=50). We then combined code frequencies with definitions and examples (Table 2). Recognizing that identities influence interpretation, findings are offered from the perspectives of White, cis-gendered females from the United States. Two authors were nonclinician faculty and two were medical students.

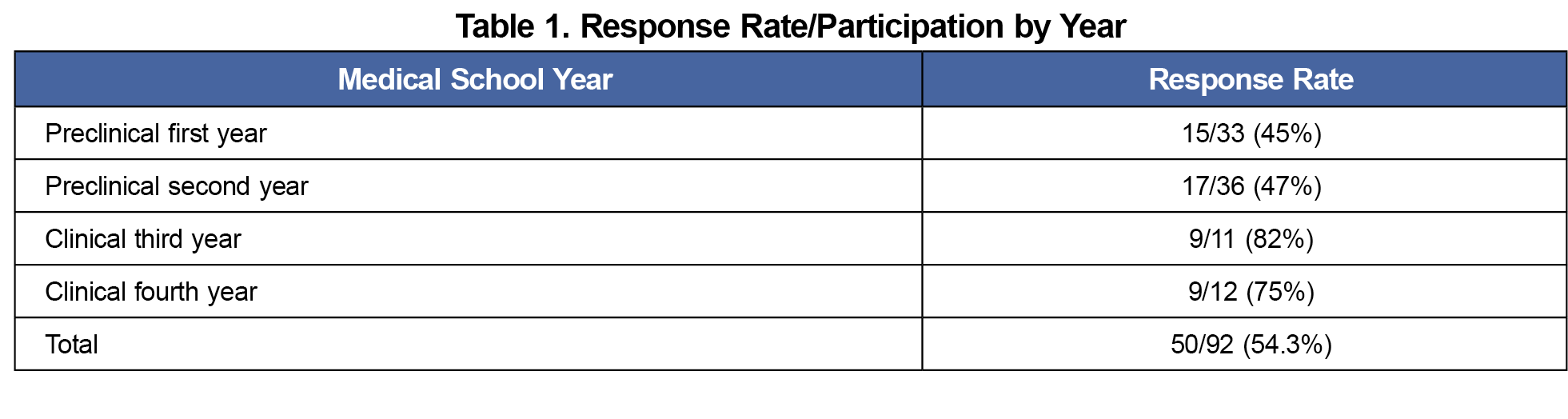

The response rate was 54% (n=32 preclinical; n=18 clinical, Table 1) and there were no observable differences between the responses of students in clinical versus preclinical training phases. Most comments (84%) reflected multiple frameworks from Irby and Hamstra and three additional themes emerged during the coding process (Table 2).

Nearly all (96%) responses referred to Irby and Hamstra’s behavior-based framework and a subset cited behaviors observable by patients (36%) and/or instructors (36%). Examples included punctuality, preparation, hygiene, and behaving politely. Two-thirds of comments cited the virtue-based framework focusing on commitment to learning and intrinsic values such as honesty, and morality. No responses referenced the full professional identity formation framework, though some addressed self-improvement, and the emergent theme “Service and Advocacy” is related to identity development.

We identified three emergent themes outside of Irby and Hamstra’s frameworks. Twenty-two percent of participants referenced the “hierarchical nature of medicine” including allegiance or uniformity, with examples like: “taking instruction,” “understanding your roles,” and “not disobeying guidelines.” Sixteen percent of responses focused on the “academic environment/hidden curriculum” in medical school. Examples related to the academic environment included “upholding the values of the institution” and examples of the hidden curriculum like “enforc[ing] compliance with organizational norms and discourag[ing] independence,” and “suppress[ing] individuality.” Finally, 8% referenced “service and advocacy” within the community or institution. Examples included campus involvement and offering feedback to inform quality improvement. Service and advocacy experiences may be sites for professional identity development.

An example of overlapping frameworks included, “Medical student professionalism is showing up on time, respecting others, and preparing to give one’s all. Reflecting on mistakes and aiming to improve nonstop.” This demonstrates the behavioral and virtue-based frameworks. Another student referenced the behavioral framework, hierarchy, and the hidden curriculum:

“Medical student professionalism [is] related to timeliness and dependability for the adequate fulfillment of predetermined requirements and expectations. However, this term is often used to control and suppress individuality and advocate for progressive policies and fair treatment.”

Participants often described professionalism through overlapping frameworks. The behavior-based framework was most prevalent, and the virtue-based framework was cited frequently. There were no references to identity formation, but emergent themes referenced sites and contexts for this development. No references to students feeling pressured to act beyond their level of competency were reported in contrast with the work of Stubbing, et al.14

Taken together, the emergent themes (“Hierarchical Nature of Medicine,” “Academic Environment/Hidden Curriculum,” and “Service and Advocacy”) describe perceptions of institutional norms and structure. Some respondents voiced concerns over the hierarchical nature of medicine and environmental factors promoting a hidden curriculum. Concepts of agency differentiate these themes from professional identity formation. Irby and Hamstra’s definition ascribes agency to physicians as they integrate into communities and structures that support their work10 while descriptions from students in this study often referred to expectations of them from the institution, restricting their agency. Findings suggest that experiences with organizational culture and values may be important in students’ definitions of professionalism.

The first step of Design Thinking in medical education, examining the perspectives of students, may provide an enriched understanding of how professionalism frameworks and other factors impact and are impacted by the learning environment.

Findings support previous research in that students experience professionalism through frameworks of behavior and virtue with most respondents referring to the behavior-based framework. Though none directly referenced identity formation, further work is needed to explore the impact of academic environments and service opportunities on perceptions of medical student professionalism.

Limitations

This study was completed at a single university; therefore, institution-specific expectations may impact data. Data collection occurred at a single point in time which may limit the scope and potentially contribute to the lack of identity development references. The limited sample size consisting of a majority of preclinical students may have impacted thematic trends. Attitudes may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic given the time frame of the survey. Qualitative analysis is subject to author positionality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the students who participated in the survey and Dr. Amy Caruso Brown who contributed to the concept for the project.

Presentation:

Preliminary findings were presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Conference Annual Spring Conference in Indianapolis, Indiana, April 2022, as, “Defining Medical Student Professionalism in the Context of Community-Based Clinical Sites,” by Roseamelia, C., Germain, L., Sitnik, E and Caruso-Brown, A.

References

- DeAngelis CD. Medical professionalism. JAMA. 2015;313(18):1837-1838. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3597

- ABIM Foundation; ACP-ASIM Foundation; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243-246. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. General competencies.ADCGM; 1999.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Assessment of Professionalism Project.American Board of Internal Medicine; 1995.

- Mueller PS. Teaching and assessing professionalism in medical learners and practicing physicians. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2015;6(2):e0011. Published 2015 Apr 29. doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10195

- Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):648-654. doi:10.1080/01421590701392903

- Passi V, Doug M, Peile E, Thistlethwaite J, Johnson N. Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: A systematic review. Int J Med Educ. 2010;1:19-29. doi:10.5116/ijme.4bda.ca2a

- Reimer D, Russell R, Khallouq BB, et al. Pre-clerkship medical students’ perceptions of medical professionalism. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):239. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1629-4

- Kirk LM. Professionalism in medicine: definitions and considerations for teaching. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2007;20(1):13-16. doi:10.1080/08998280.2007.11928225

- Irby DM, Hamstra SJ. Parting the clouds. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1606-1611. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001190

- Sandars J, Goh PS. Design thinking in medical education: the key features and practical application. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520926518. Published 2020 Jun 4. doi:10.1177/2382120520926518

- McLaughlin JE, Wolcott MD, Hubbard D, Umstead K, Rider TR. A qualitative review of the design thinking framework in health professions education. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):98. Published 2019 Apr 4. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1528-8

- Anderson J, Calahan CF, Gooding H. Applying design thinking to curriculum reform. Acad Med. 2017;92(4):427-427. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001589

- Stubbing EA, Helmich E, Cleland J. Medical student views of and responses to expectations of professionalism. Med Educ. 2019;53(10):1025-1036. doi:10.1111/medu.13933

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Braun V, Clarke V. Teaching thematic analysis: overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist. 2013;26(2):120-123.

There are no comments for this article.