Objectives: This project analyzed the culture of safety quality improvement at the Family Medicine Center (FMC). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Culture of Safety Survey was used as a benchmark for internal and external comparison.

Methods: The AHRQ Culture of Safety Survey was administered to health care staff in 2015, 2017, and 2019, respectively, at the Family Medicine Center. Baseline perceptions of safety and quality were established using the data from the AHRQ Culture of Safety Survey in 2015. We performed multiple large-scope quality improvement projects that focused on identified deficiencies. The changes in perception were monitored over time every 2 years. We analyzed the results using the Kruskal-Wallace test (P=.05).

Results: The AHRQ Culture of Safety Survey showed statistically significant improvement in patient centeredness, effectiveness, timeliness, efficiency, equitableness, and overall patient safety from 2015 to 2019. Some inconsistencies were seen between different sections of responses, likely due to wording interpretations by the participants.

Conclusion: Overall, the AHRQ Culture of Safety Survey is an effective way to help monitor employee perception of multiple domains that lead to a safe and effective clinical environment as compared to other practices across the country. Clinic-wide implementation of quality and patient care strategies resulted in significant improvements in nearly every category of the survey.

Patient safety has come to the forefront since the publication of the Institute of Medicine's report To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System in 1999.1 Tracking patient safety and clinic culture allows for continual improvement.2–6 The Family Medicine Center (FMC) used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Culture of Safety Survey to measure the clinic’s patient safety culture by assessing physician and staff perceptions of clinic patient safety and quality outcomes. Teamwork is a core feature of successful health care quality improvement, yet there is little evidence on best practices for implementation and support of teamwork initiatives that directly impact safety and quality.2,7

The Family Medicine Center (FMC) clinic is a recognized patient-centered medical home (PCMH) for a community-based family medicine residency program. Senior leadership within the FMC sought to improve the culture of safety and quality through targeted, evidence-based systems improvement efforts. These efforts included error reporting mechanisms, regular safety meetings by department leaders, and the creation of a resident safety chief position.5,8 The goal of these initiatives has been to maintain high-quality health care despite regular resident turnover.9 The FMC utilized the AHRQ Culture of Safety Survey as a benchmark for internal and external comparison. The AHRQ’s Medical Office Survey on Patient Safety Culture is broken down into several categories such as “Communication About Error” and “Office Processes and Standardization” with additional questions on patient safety issues and exchanging patient information with other entities, which are respectively referred to as the “A” and “B” series of questions in the survey tool. The FMC has been working to balance initiatives to enhance patient care and graduate medical education experience with staff’s fatigue associated with frequent changes to processes, workflow, and reporting requirements in a fast-paced clinic.10,11

The purpose of this study was to longitudinally evaluate the net impact on patient safety metrics when the organization’s leadership set its improvement as a company-wide goal. As a community family medicine residency program, it is crucial to include a focus on patient safety outcomes as part of our mandate to graduate practice-ready physicians.

This study was conducted at the FMC with responses provided by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other clinic staff members. Printed surveys were made available throughout the facility.

Study Design and Data Collection

The medical office survey, an expansion of AHRQ’s Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture, was designed to measure an office’s patient safety culture. The survey consisted of 26 questions in five different series and an additional 22 survey questions about organizational culture. Paper surveys were made available to the approximately 80 FMC employees in 2015, 2017, and 2019. The printed surveys were made available throughout the clinic and administrative spaces. We used the Kruskal-Wallace test to analyze the data with an α of 0.05. This project was approved by the Lutheran Health Network Institutional Review Board (LHN# 18-511).

A total of 112 surveys were completed by FMC employees. Statistically significant improvements in patient centeredness, effectiveness, timeliness, efficiency, equity, and overall patient safety were seen from baseline results to final results. In the 2015 baseline assessment 33 participants completed the survey, and in 2017 and 2019 48 and 44 participants, respectively, submitted the survey.

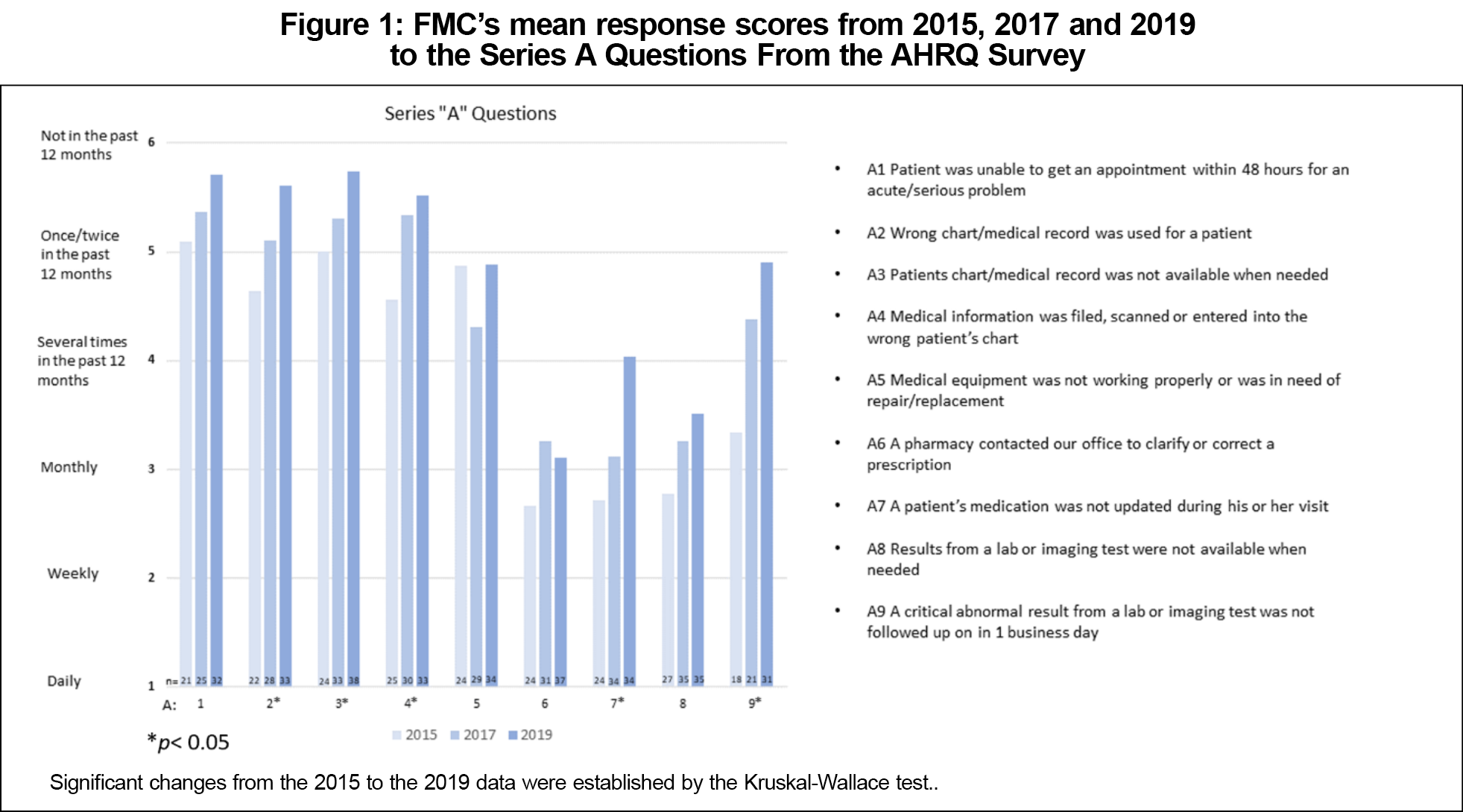

In the “A” series question about access to care within 48 hours, 55% in 2015, 65% in 2017, and 91% in 2019 of employees had a positive response. The FMC leadership set the goal of having a mean value ≥5 for the “A” series questions (Figure 1). We met these goals for access to health care providers, chart access, and properly working medical equipment. This study demonstrated significant improvement in five the of the nine areas, while only four the nine areas met the leadership’s target.

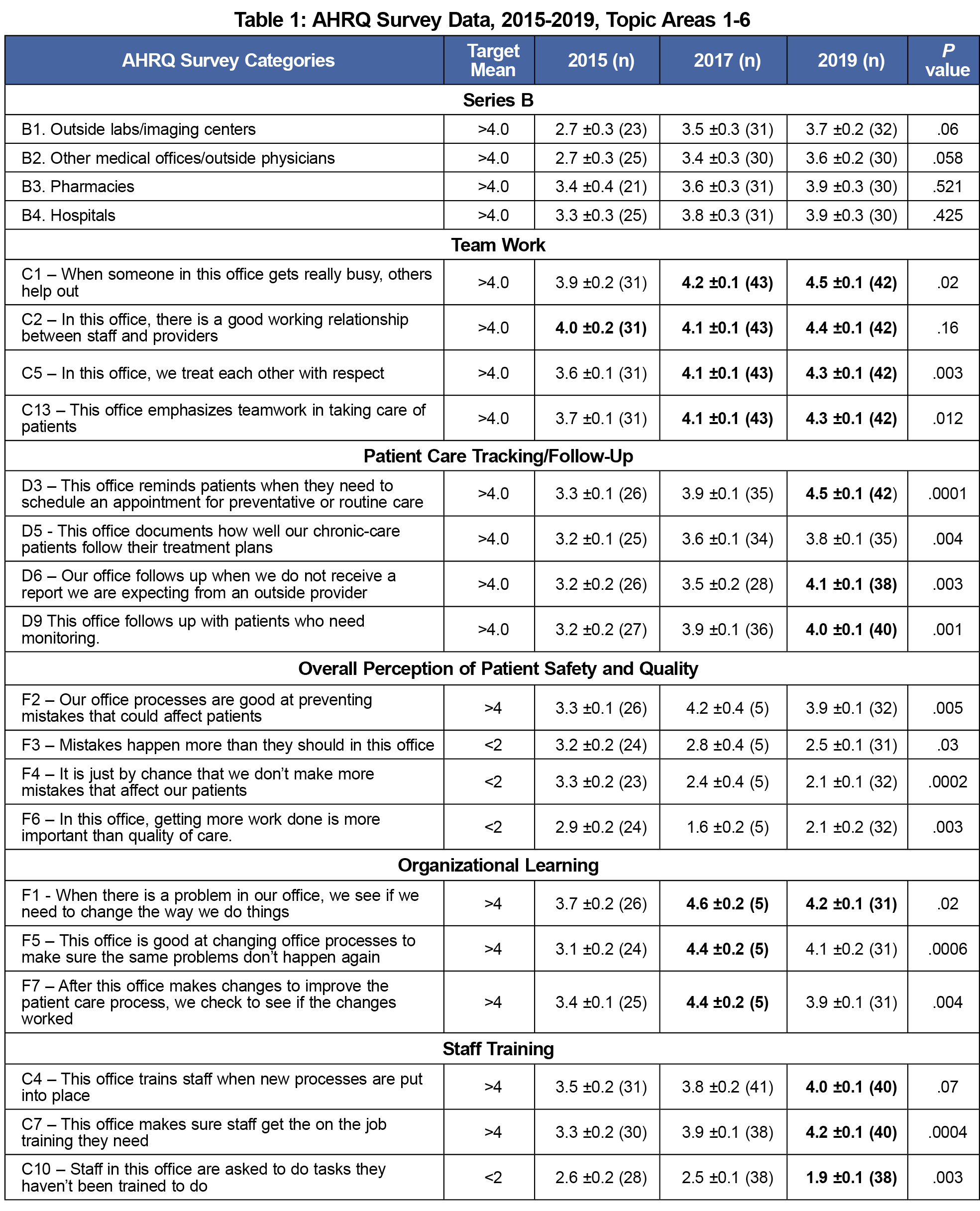

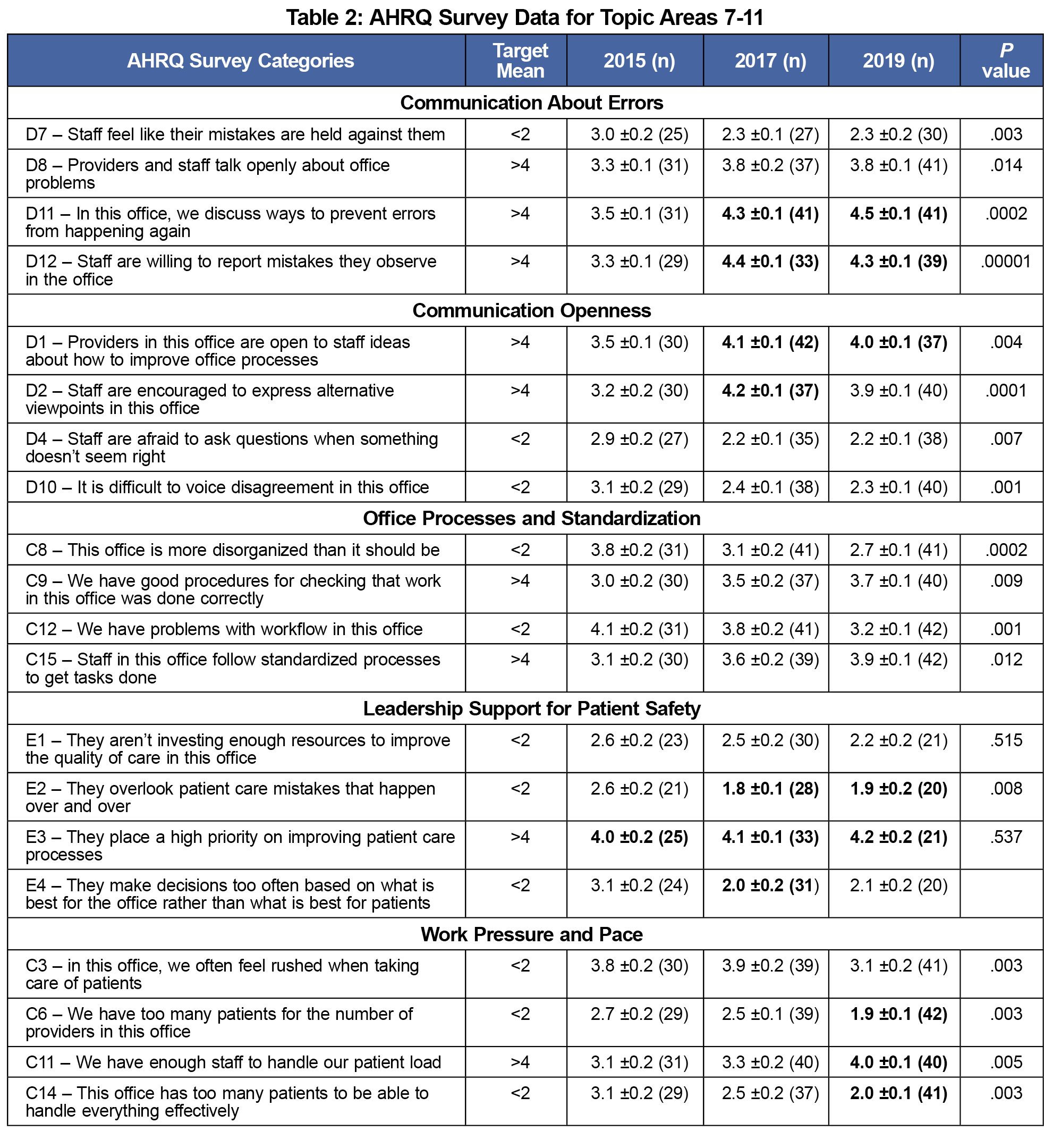

Tables 1 and 2 represent the results of the next 11 areas of the AHRQ survey. The bold font entries in the tables show where the FMC leadership’s goal was achieved. There were instances where significant changes were observed even if the leadership’s goal wasn’t achieved.

In the “B” series of questions, values of ≤2 were desired for negative questions, and ≤4 for positive questions. Results were below the national average for interfacing with various external medical settings. From 2015 to 2019 we saw significant improvement in teamwork, with three out of four responding “very good” to the prompt “when someone in this office gets really busy, others help out.” We also saw significant improvement in employee perceptions of patient care tracking and follow-up. The questions concerning organization learning showed there was a significant decrease in positive responses.

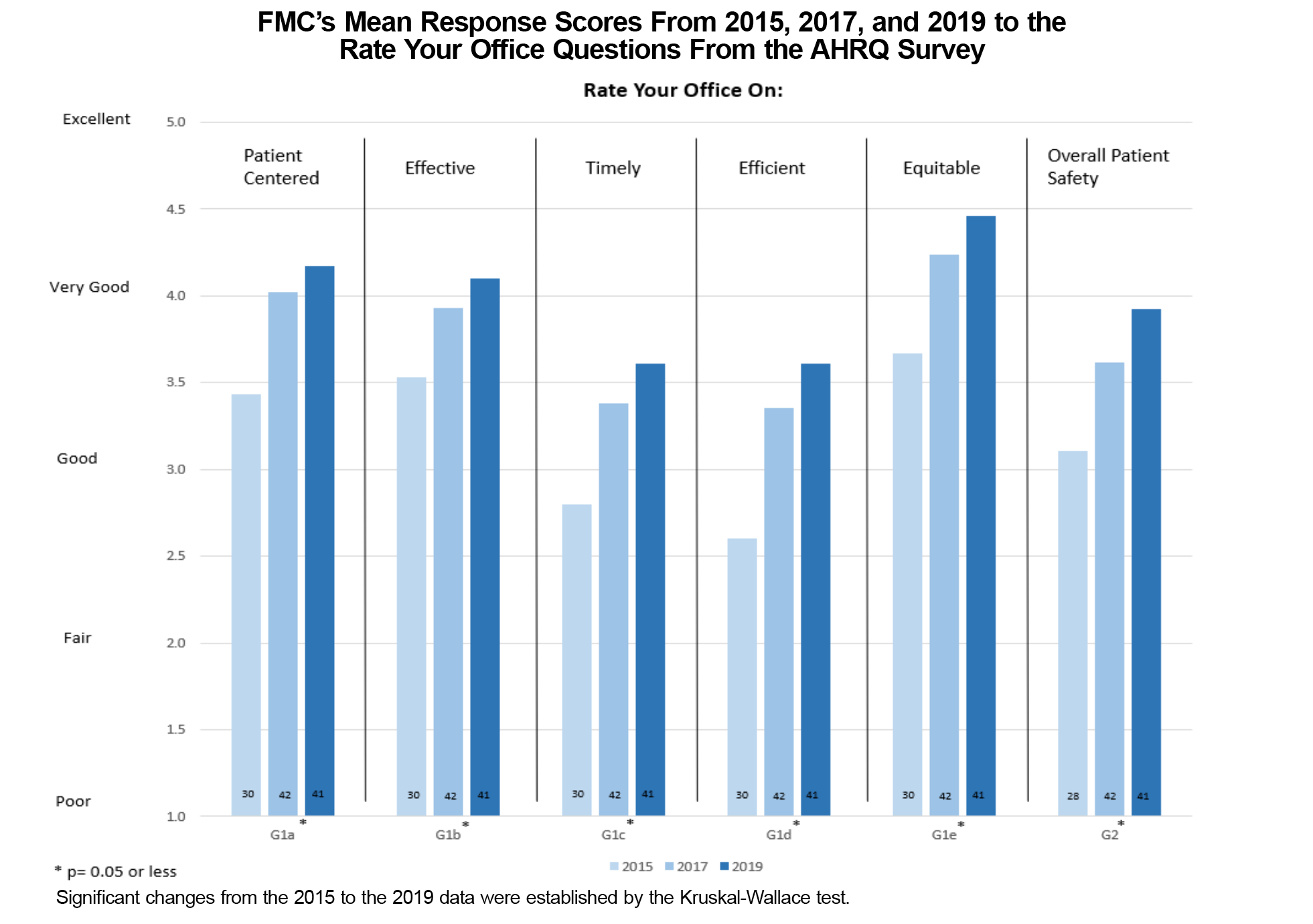

Figure 2 shows the results of employee’s rating their clinic on six different areas. The leadership set a score of 4 out of 5 or more as the target for each category. All six areas showed a significant increase in the employee’s rating of their office.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, we had a small number of participants, and some of the participants did not complete all components of the survey. Some parts of the survey inexplicably had as few as five participants respond (Table 1, 2017 data set). Missing data and nonresponse bias may be present, and those with strong negative or positive feelings may have been more likely to respond. Additionally, there were some survey questions with interpretation variances leading to inconsistent results from similar questions. Also, we were unable to gather specific baseline characteristics regarding employees’ role in the clinic and years of practice at the clinic as many of the surveys were left blank for these questions. Therefore, the anonymous paper-based survey format did not allow for intra-cohort analysis between physicians, nurses and other staff participants. Finally, since we followed the AHRQ representative’s advice on how to make the surveys available to the employees we were not able to determine the actual response rate.

We improved patients’ access to care at the FMC, interclinical communication, and team and interprofessional interactions. Overall perception of patient safety and quality has shown statistically significant improvement in four out of four responses. However, multiple areas still need improvement to reach benchmarks and the national average for top box responses. The organizational learning survey indicated a discordance between questions F1 and F5 (change management perceptions). These discordances could be attributed to inconsistent interpretation of survey questions or could be due to safety inertia, where easily modified issues are addressed but larger, global issues are not addressed. Another area where we noted a discordance was between questions D8 and D12. Providers and staff do not reportedly speak openly about problems in the office in the first question. However, staff are willing to report mistakes they observe in the office in the second question. The wording of “talk openly about office problems” allows for variations in interpretation, eg, venting dissatisfaction openly versus discussing concerns in appropriate settings.

In addition to the learning opportunities for our family medicine residents, the quality improvement projects focused on identified workflow inefficiencies such as implementation of a new electronic medical record and telephone system, along with robust screening protocols. Key activities that affected the described changes included daily team huddles to foster communication, clinical staff uniforms to build a sense of community, development of an FMC committee with diverse participants, and the creation of a resident quality safety chief to identify and correct errors. Finally, to the best of our knowledge there are no previous publications that used AHRQ’s Culture of Safety Survey for longitudinal patient care benchmarks as part of a family medicine residency’s physician training.

The results from our study helped compare patient safety culture survey results from the FMC with other medical offices. Our clinic has progressed significantly from 2015 to 2019, but there is room for continued improvement through more focused projects.

References

- Lawati MHA, Dennis S, Short SD, Abdulhadi NN. Patient safety and safety culture in primary health care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):104. doi:10.1186/s12875-018-0793-7

- Kassam A, Sharma N, Harvie M, O’Beirne M, Topps M. Patient safety principles in family medicine residency accreditation standards and curriculum objectives: implications for primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(12):e731-e739.

- Friedberg MW, Coltin KL, Safran DG, Dresser M, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC. Associations between structural capabilities of primary care practices and performance on selected quality measures. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(7):456-463. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00006

- Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Goeschel C, et al. Creating high reliability in health care organizations. Health Serv Res. 2006; 41(4p2). doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00567.x

- Musso MW, Vath RJ, Rabalais LS, et al. Improving patient safety communication in residency programs by incorporating patient safety discussions into rounds. Ochsner J. 2017;17(3):273-276.

- van der Leeuw RM, Lombarts KMJMH, Arah OA, Heineman MJ. A systematic review of the effects of residency training on patient outcomes. BMC Med. 2012;10(1):65. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-65

- Brennan SE, Bosch M, Buchan H, Green SE. Measuring team factors thought to influence the success of quality improvement in primary care: a systematic review of instruments. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):20. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-20

- O’Toole TP, Cabral R, Blumen JM, Blake DA. Building high functioning clinical teams through quality improvement initiatives. Qual Prim Care. 2011;19(1):13-22.

- Lawrence DM. Analysis & commentary. How to forge a high-tech marriage between primary care and population health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):1004-1009. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0167

- Ead H. Change fatigue in health care professionals--an issue of workload or human factors engineering? J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30(6):504-515. doi:10.1016/j.jopan.2014.02.007

- Kansagara D, Tuepker A, Joos S, Nicolaidis C, Skaperdas E, Hickam D. Getting performance metrics right: a qualitative study of staff experiences implementing and measuring practice transformation. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 2):S607-S613. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2764-y

There are no comments for this article.