Background and Objectives: Quality improvement capacity is defined as ongoing commitment to sustained quality improvement (QI) and requires knowledge of QI methods and commitment to QI activities from practice leadership and staff. The aim of this project was to identify the major facilitators and barriers to developing quality improvement capacity in a teaching practice of a department of family medicine.

Methods: We conducted an exploratory, sequential, mixed-methods study, inviting key informants to participate in qualitative interviews and then conducting a survey of faculty, resident physicians, and staff at a community residency teaching practice affiliated with an academic medical center in the Midwest United States.

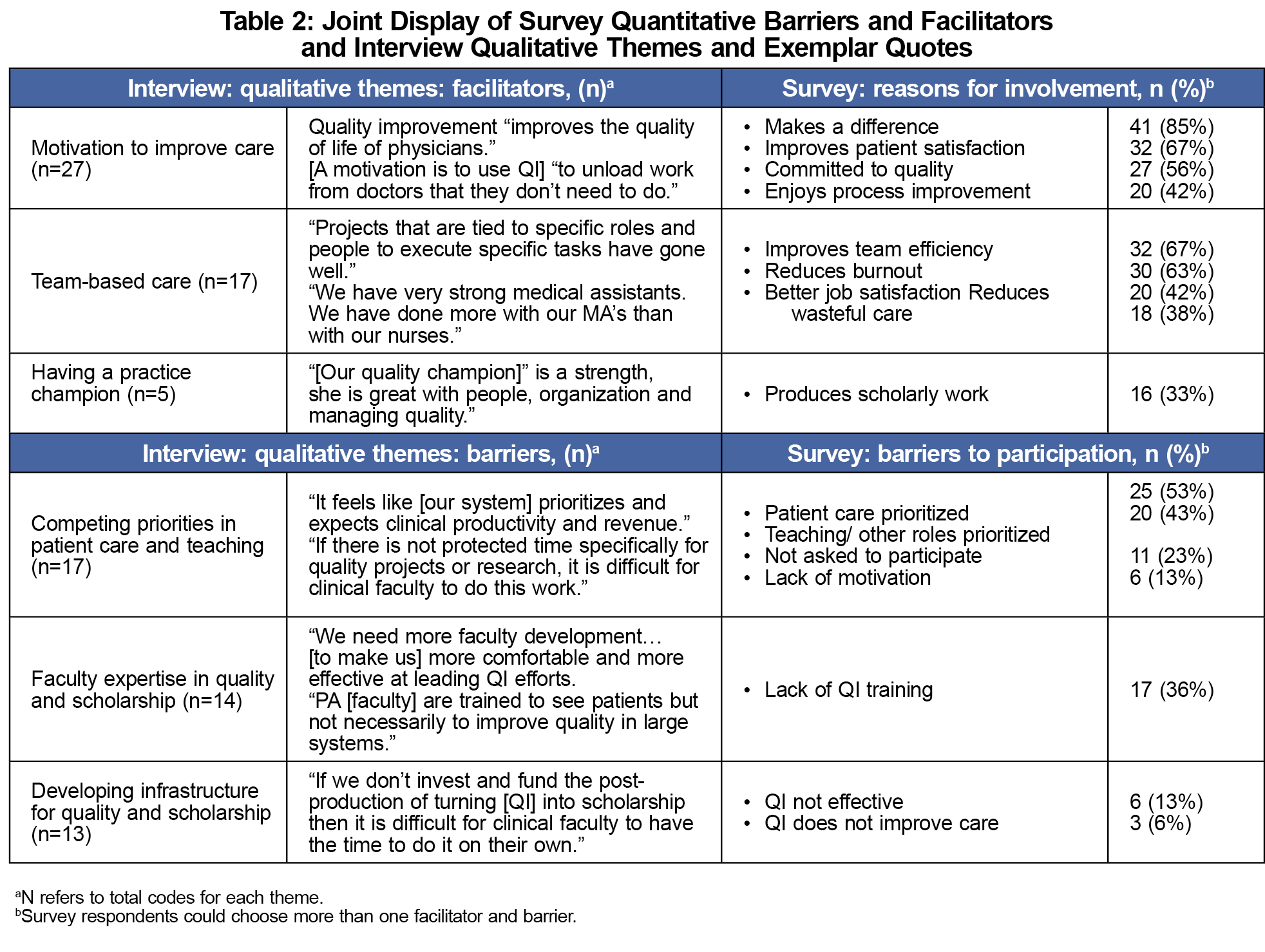

Results: Among 12 qualitative key informant interviewees, facilitators of QI capacity included a strong motivation to provide high-quality care and a desire to leverage team-based care in QI interventions. Barriers included competing clinical and educational priorities, lack of faculty expertise in quality and scholarship, and lack of infrastructure to turn QI into scholarship. The survey response rate was 75% (48 of 64 total team members). The most common motivation for participation in QI work was “making a difference” (41, 85%), while the biggest barriers were prioritization of patient care (25, 53%), and teaching (19, 40%).

Conclusion: This mixed-methods study identified key barriers and facilitators to QI capacity, of which addressing competing priorities, improving QI training, and creating infrastructure for scholarship may improve QI capacity.

Quality improvement (QI) capacity is defined as ongoing commitment to sustained QI, requiring knowledge of methods, practice leadership, and staff commitment to QI activities.1 QI capacity is necessary for family medicine residency programs to meet Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements for QI education, provide high-quality and equitable care to patients and communities, and achieve the scholarly activity needs of academic faculty.2

Prior studies of QI capacity have been conducted as preimplementation for large regional quality collaboratives of primary care practices, and have most often used either qualitative interviews or survey tools rather than a mixed-methods approach.3–11 This research leaves a gap in understanding how to assess QI capacity in departments of family medicine (DFM) that do have external supports through collaboratives or practice facilitation. This mixed-methods study aimed to identify the major barriers and facilitators in a small DFM to support future change. We hypothesized that having faculty champions and training, staff engagement, and having protected time would emerge as key facilitators.

This exploratory, sequential, mixed-methods study first qualitatively explored the barriers and facilitators affecting QI capacity and then quantified their extent and importance via a quantitative survey. The study was conducted at the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences DFM Comprehensive Care Center practice (CCC), an academic residency teaching practice located in Toledo, Ohio, staffed by 11 family medicine faculty, 14 resident physicians, and 7 part-time physician assistant (PA) faculty (total 3.5 clinical full-time equivalents [FTE]) with a total of 9.6 clinical FTE. The DFM and PA faculty also support a PA training program. This study was approved as exempt and not regulated by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (ID: HUM00197797).

Qualitative Methods

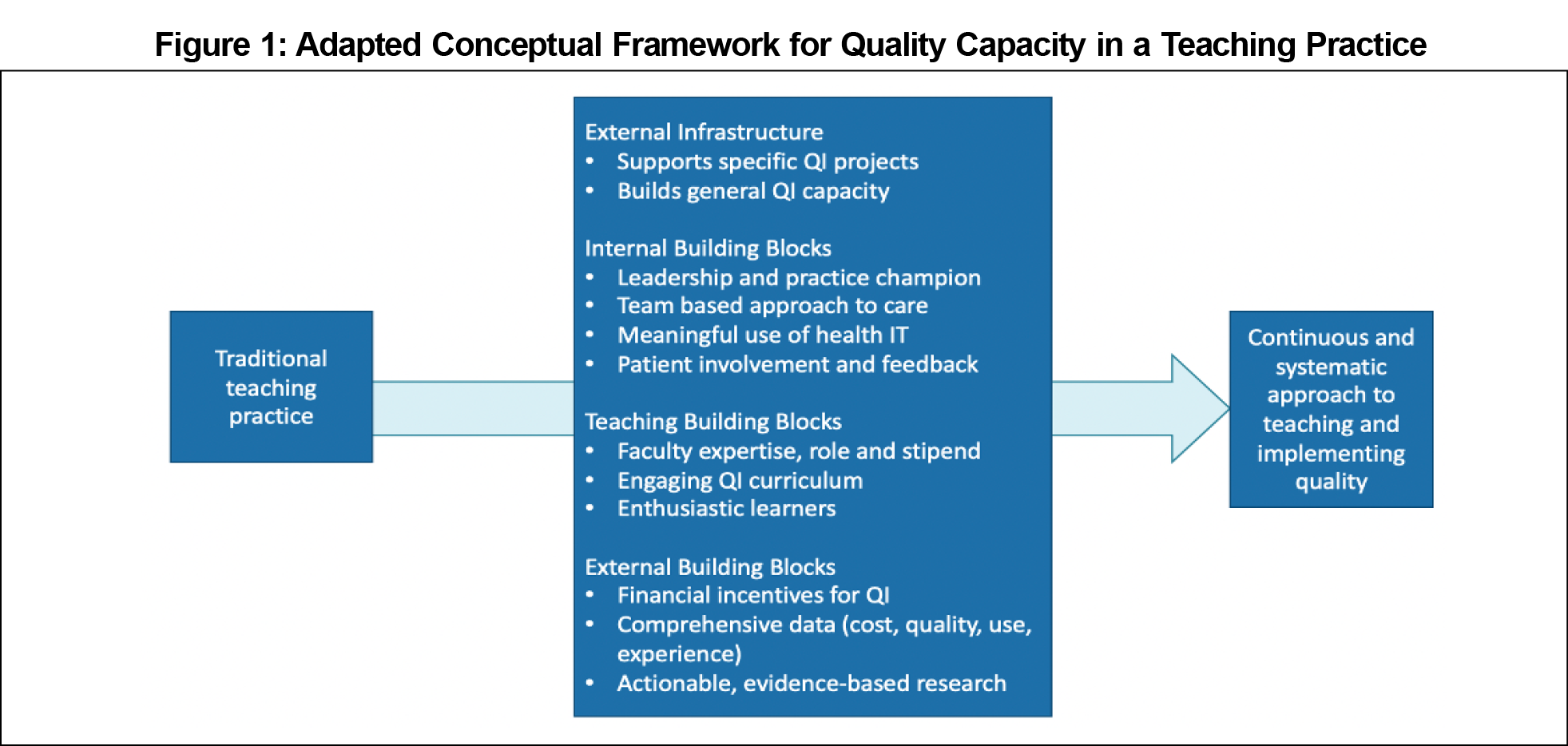

We adapted the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) conceptual framework for creating QI capacity in primary care to our setting and based our semistructured interview guide on the constructs (Figure 1).1 We interviewed 12 key informants identified by department leaders as having insight into QI and scholarship efforts in the practice and system. One author (L.O.) obtained verbal consent and performed video or phone interviews between April 2021 and June 2021. Two authors performed a thematic analysis, starting with inductive open coding (L.O.), development of a code book and themes (L.O., T.W.), then triangulation of themes with the conceptual framework and discussion with two additional authors (P.S., L.S.).12 Saturation was met when all predefined pertinent roles (faculty, resident, office manager, office nurse, organizational quality leader) were interviewed and no new themes emerged.13,14

Quantitative Methods

We created an 11-item survey to quantify findings from our qualitative themes, adapted from the Quality Improvement Change Assessment (QICA), a survey tool developed for a QI collaborative on cardiovascular risk improvement in small primary care practices.3 We invited all 64 team members at the practice to complete anonymous paper surveys in August and September 2021. We collected data on role and years at the practice and performed descriptive statistical analysis for all items. We used Microsoft Excel for all analyses.

Mixed-Methods Integration

Integration occurred at the point of survey creation from qualitative theme and presentation of barriers and facilitators in a joint display.15

Qualitative Themes

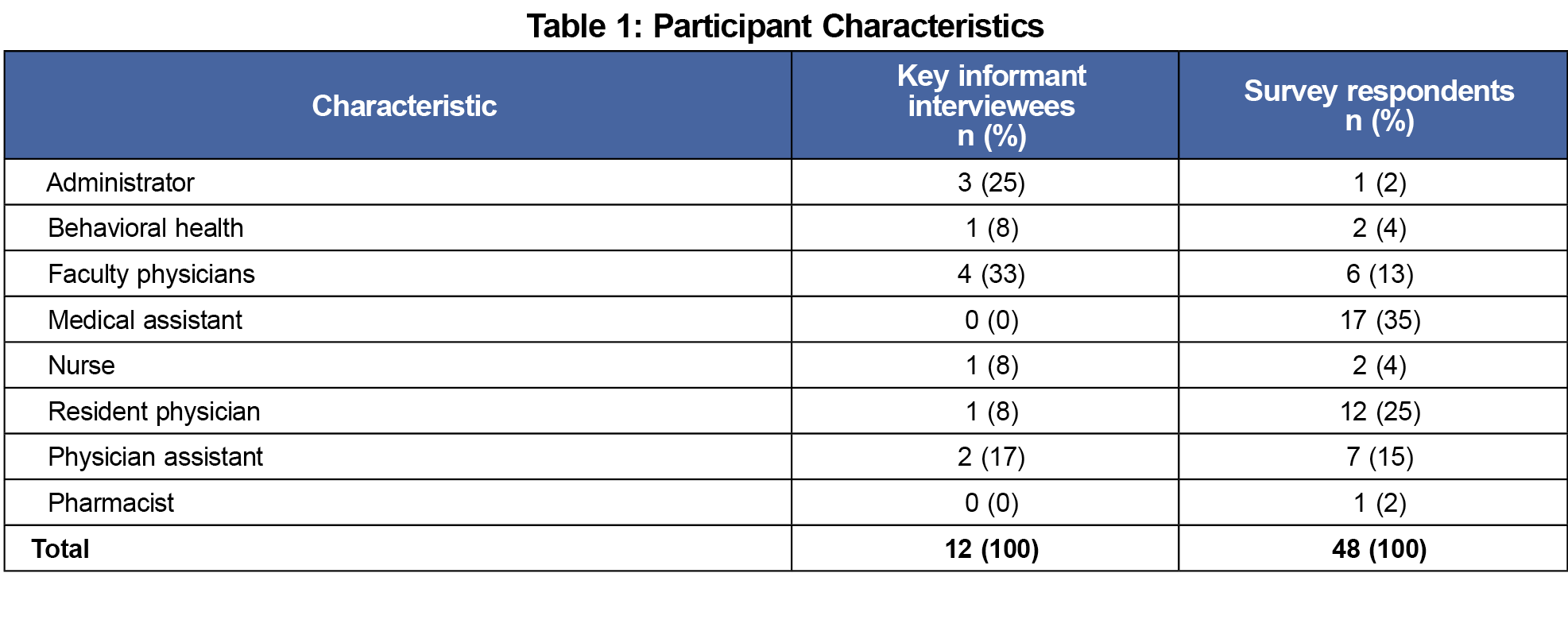

Of 12 key informants, two were organizational quality leaders, and 10 were CCC practice team members (Table 1). We generated two key facilitator themes: team member motivation to improve care and leveraging team-based care. We generated three barrier themes: addressing competing priorities of patient care and teaching, the need for faculty expertise in quality and scholarship, and developing infrastructure for quality and scholarship (Table 2).

Quantitative Results

The response rate was 48 out of 64 team members (75%), with the most common role being medical assistant (Table 1). The most common reason for involvement in QI was making a difference (41, 85%), while the biggest barriers to participation were prioritization of patient care (25, 53%) and teaching (20, 43%; Table 2).

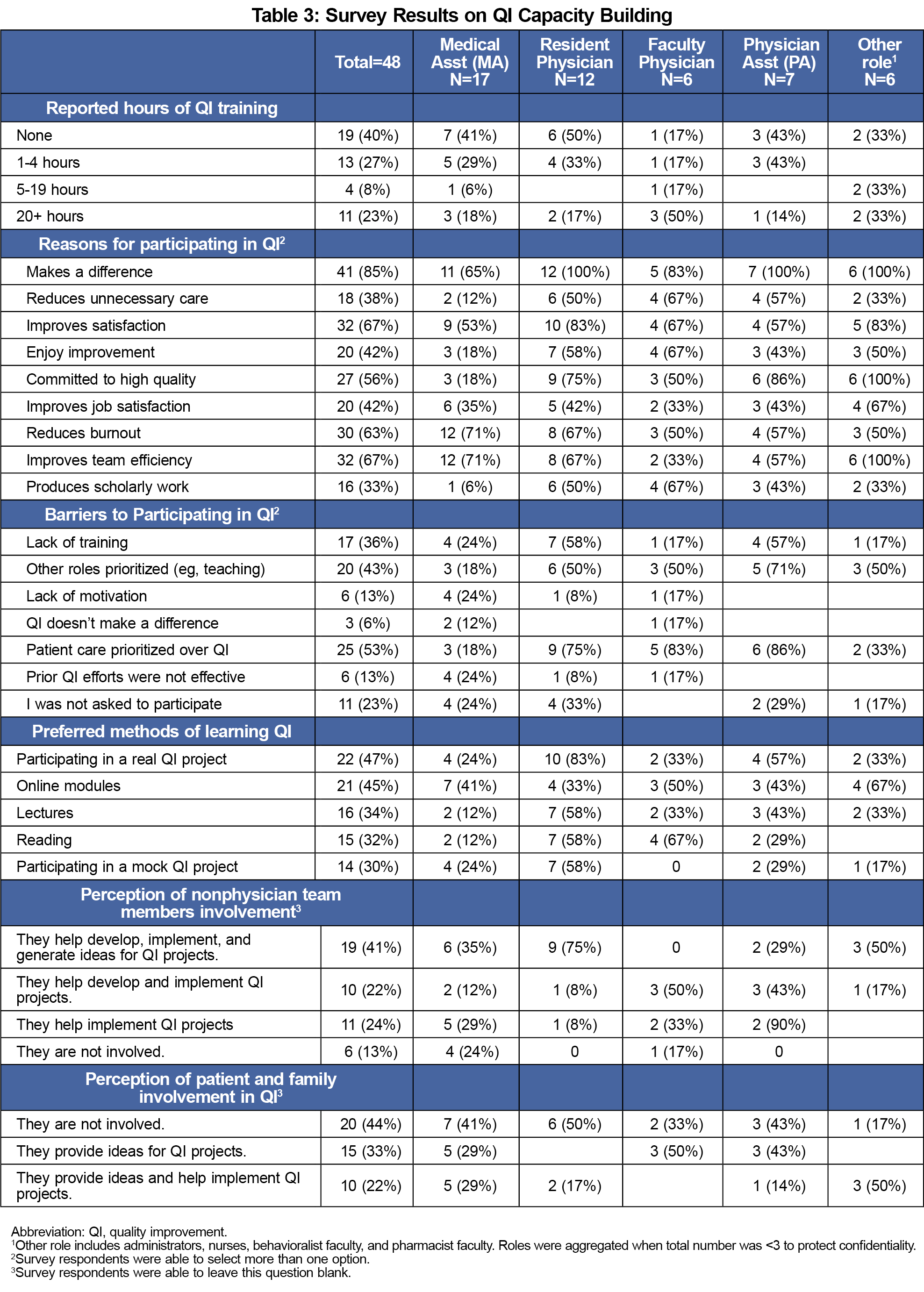

Many respondents reported no prior QI training (n=19, 40%). The most desired modalities for future QI learning among all participants were participating in an actual QI project (22, 47%) or online modules (21, 45%). Less than half of respondents perceived that nonphysician team members were fully integrated into QI efforts (19, 41%), and almost half believed that patients and families were not involved in QI (19, 41%; Table 3).

The main contribution of this study is to characterize major barriers and facilitators to QI capacity in the residency teaching practice of a DFM using a mixed-methods approach. Prior studies identified competing patient care priorities as a key barrier. Qualitative results identified barriers unique to residency teaching practices that must be addressed to develop QI capacity—competing teaching responsibilities and the need for infrastructure to support abstract, poster, and manuscript writing for resident projects and faculty promotion. Quantitative results complemented these findings by identifying the need to train MAs, PA faculty and other team members in addition to faculty leaders and resident physicians, consistent with other studies showing that PA faculty have limited QI training.16 Our results call for basic QI education for all team members to improve engagement and participation in addition to more intensive training to develop and support a subset of quality champions and team members to produce scholarship.17 Respondent preference for learning via participation in real QI projects should be incorporated among the options for QI training previously described in the literature.18 While addressing competing priorities is challenging, our findings supported the addition of a faculty member to the DFM with experience and protected time to support scholarship production from QI.

We identified two key facilitators: motivation to improve and team-based care. Staff members were motivated to unload work from physicians and use QI efforts to better delegate and streamline tasks. Staff participation is particularly crucial in residency practices to sustain QI efforts.19 Leveraging each person’s intrinsic motivation to provide high-quality care and increasing staff participation are strategies that may be successful in improving QI capacity without worsening physician burnout.

This study is limited by its single-site setting. Responses of key informants and survey respondents may not be fully representative of all stakeholders and team members; specifically, the key informant interviews lacked participation by medical assistants. Our mixed-methods approach may be helpful to other departments of family medicine seeking to understand barriers and facilitators to QI capacity to plan future change.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

This work was supported by internal funding from the University of Toledo Department of Family Medicine.

References

- Taylor EF, Peikes D, Genevro J, Meyers D. Creating Capacity for Improvement in Primary Care.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. Accessed April 25, 2022. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/capacity-building/pcmhqi1.htm

- Headrick LA, Baron RB, Pingleton SK, et al. Teaching for Quality: Integrating Quality Improvement and Patient Safety across the Continuum of Medical Education.Association of American Medical Colleges; 2013. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/26316/download

- Parchman ML, Anderson ML, Coleman K, et al. Assessing quality improvement capacity in primary care practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):103. doi:10.1186/s12875-019-1000-1

- Helfrich CD, Li YF, Sharp ND, Sales AE. Organizational readiness to change assessment (ORCA): Development of an instrument based on the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci.

- Knight AW, Dhillon M, Smith C, Johnson J. A quality improvement collaborative to build improvement capacity in regional primary care support organisations. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(3):e000684. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000684

- Wolfson D, Bernabeo E, Leas B, Sofaer S, Pawlson G, Pillittere D. Quality improvement in small office settings: an examination of successful practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10(1):14. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-10-14

- Bobiak SN, Zyzanski SJ, Ruhe MC, et al. Measuring practice capacity for change: a tool for guiding quality improvement in primary care settings. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(4):278-284. doi:10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181bee2f5

- Ruhe MC, Carter C, Litaker D, Stange KC. A systematic approach to practice assessment and quality improvement intervention tailoring. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(4):268-277. doi:10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181bee268

- Butler JM, Anderson KA, Supiano MA, Weir CR. “It feels like a lot of extra work”: resident attitudes about quality improvement and implications for an effective learning health care system. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):984-990. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001474

- Varley AL, Kripalani S, Spain T, et al. Understanding factors influencing quality improvement capacity among ambulatory care practices across the midsouth region: an exploratory qualitative study. Qual Manag Health Care. 2020;29(3):136-141. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000255

- Crittendon DR, Cunningham A, Payton C, et al. Organizational readiness to change: quality improvement in family medicine residency. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2020;4:14. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2020.441200

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- LaDonna KA, Artino AR Jr, Balmer DF. Beyond the Guise of Saturation: Rigor and Qualitative Interview Data. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(5):607-611. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00752.1

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753-1760. doi:10.1177/1049732315617444

- Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134-2156. PMID:24279835 doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Kayingo G. Quality improvement education for physician assistant students: A national cross-sectional study. JAAPA. 2015;28(11):1. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000471297.33479.90

- Bonawitz K, Wetmore M, Heisler M, et al. Champions in context: which attributes matter for change efforts in healthcare? Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):62. doi:10.1186/s13012-020-01024-9

- Bodenheimer T, Dickinson WP, Kong M. Quality improvement models in residency programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):15-17. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00556.1

- Coleman KF, Krakauer C, Anderson M, et al. Improving quality improvement capacity and clinical performance in small primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(6):499-506. doi:10.1370/afm.2733

There are no comments for this article.