Introduction: With the transition of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 exam to pass-fail, residency directors are exploring alternative objective approaches when selecting candidates for interviews. The Medical Student Performance Evaluations (MSPE) portion of the application may be an area where objectivity could be provided. This study explored program directors’ (PDs) perspectives on the utility of the MSPE as a discriminating factor for residency candidate selection.

Methods: We invited PDs of primary care residencies listed in the American Medical Association FRIEDA database to participate in a mixed-methods study assessing opinions on the MSPE, and the importance of student skills and application components when considering a candidate for interview. We obtained summary statistics for Likert-scale responses. We used inductive thematic analysis to generate themes from open-ended comments.

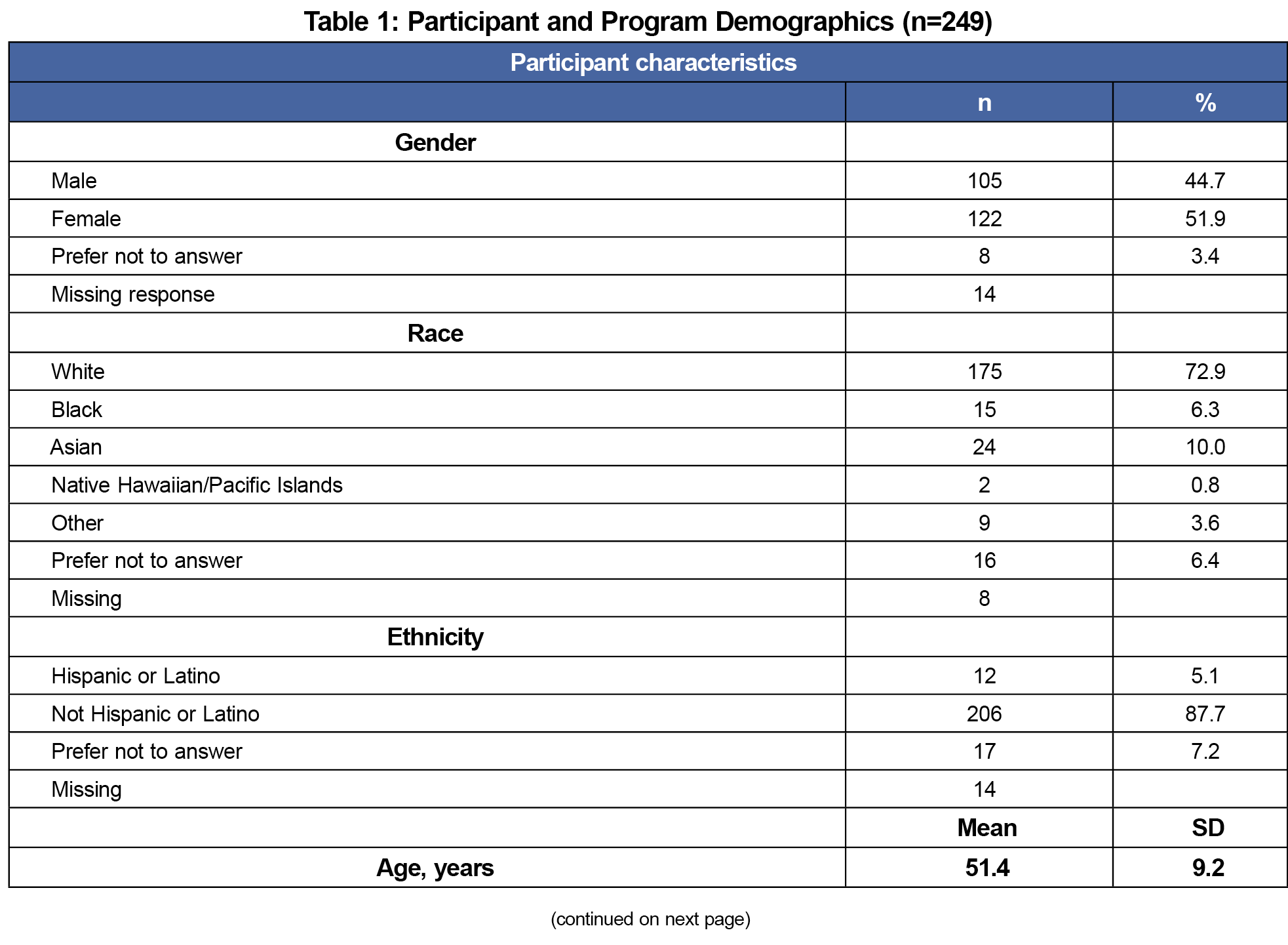

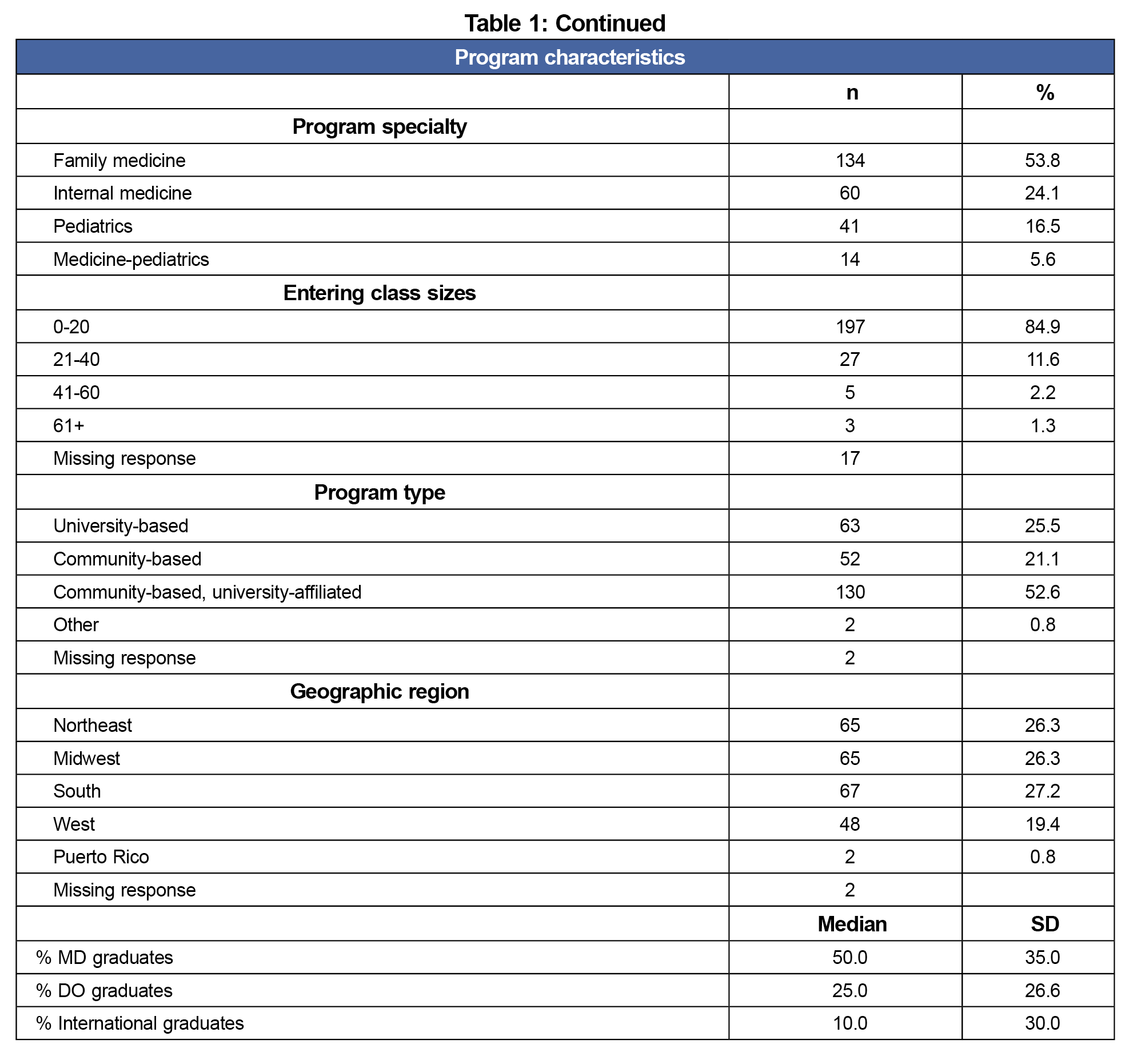

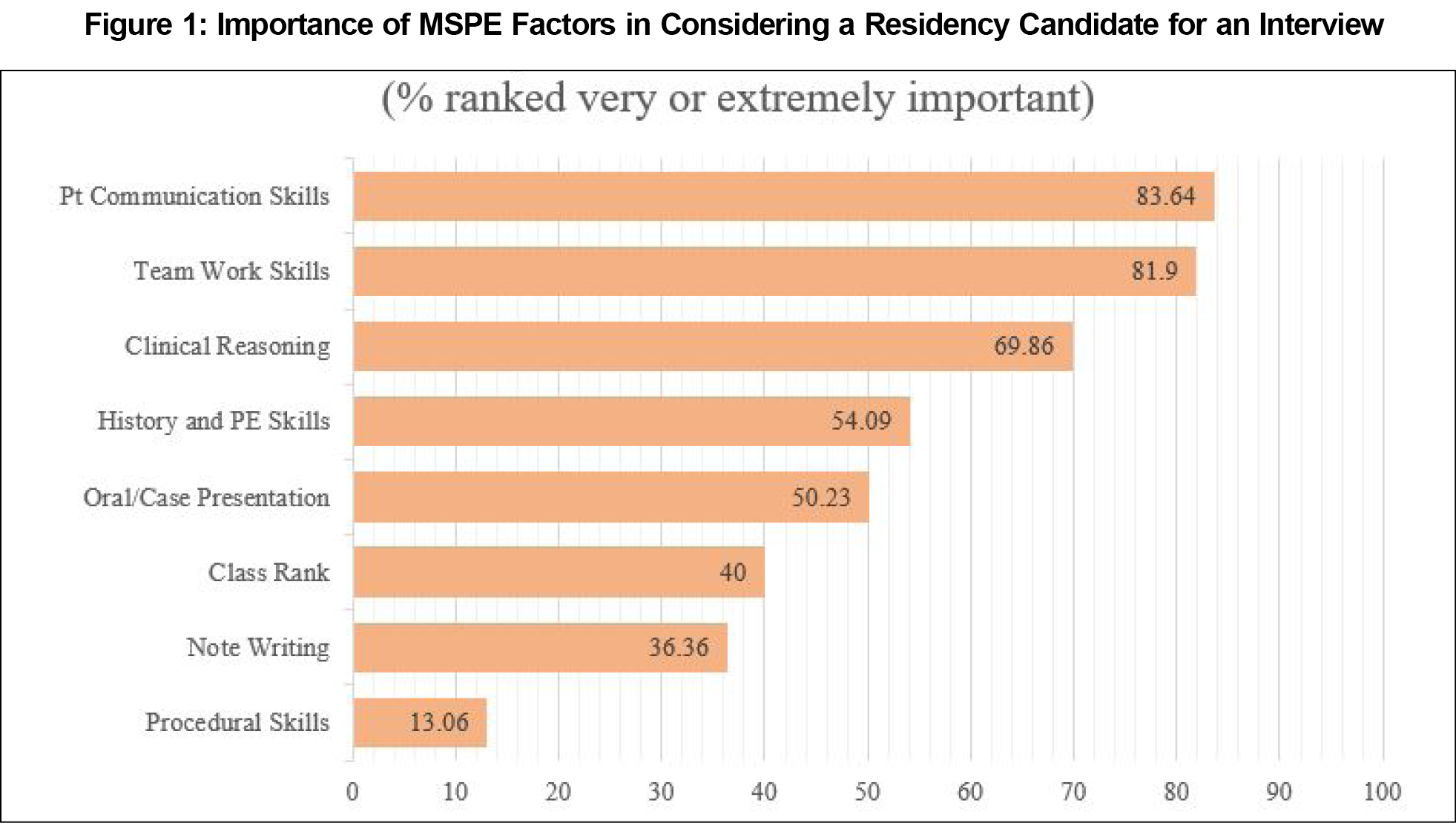

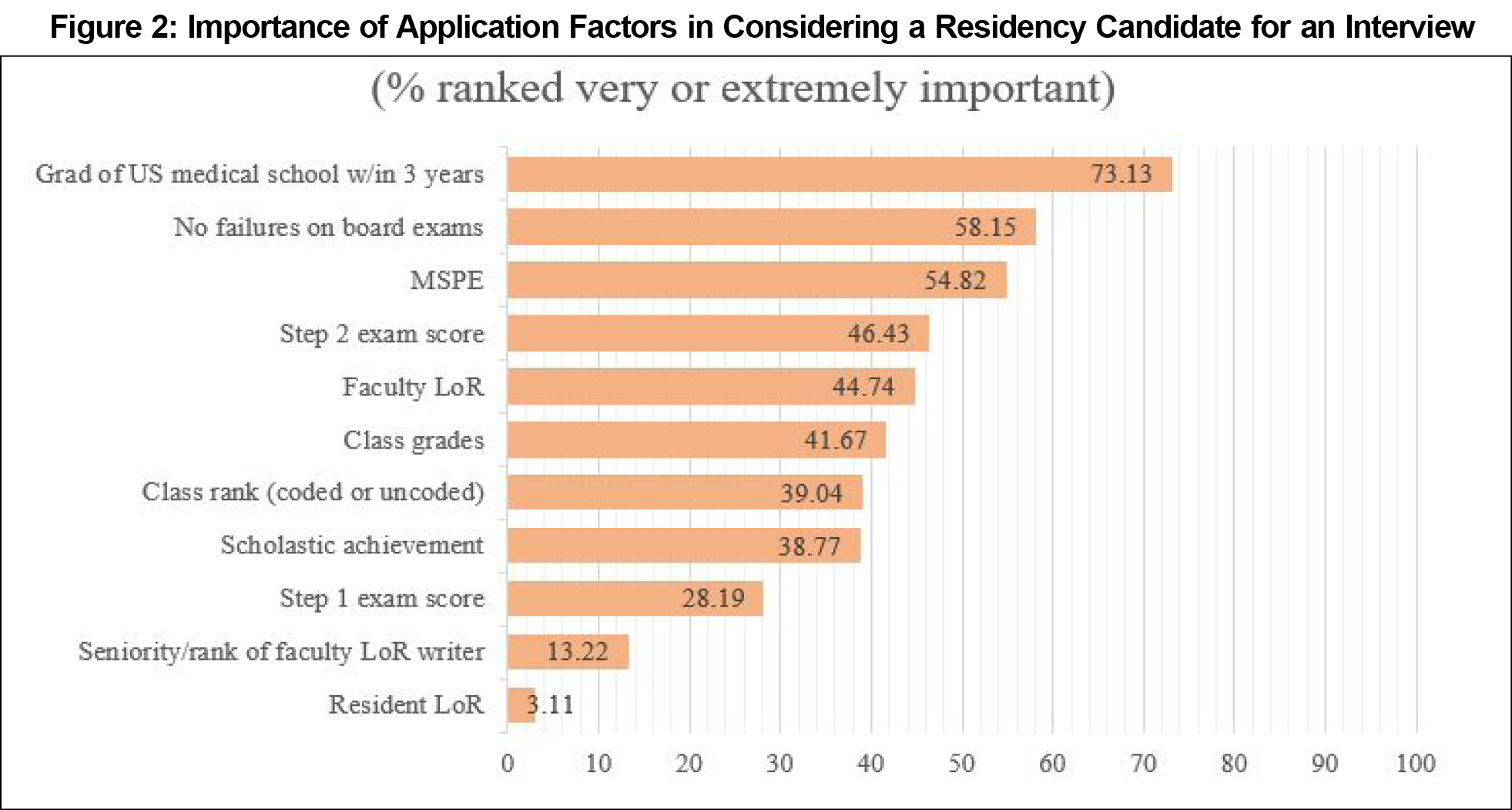

Results: Two hundred forty-nine PDs completed the survey (response rate=15.9%). Patient communication (83.6%) and teamwork (81.9%) were rated as very/extremely important skills, and being a graduate of a US medical school in the past 3 years (73.1%), no failures on board exams (58.2%), and MSPEs (54.8%) were rated as very/extremely important application components. Six hundred seventy-eight open-ended comments yielded themes related to desire for more transparency and standardization, importance of student attributes and activities, and other important components of applications.

Conclusion: PDs place a high value on the MSPE but find it limited by concerns over validity, objectivity, and lack of standardization. The quality of MSPEs may be improved by using a common language of skill attainment such as the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Entrustable Professional Activities and using the document to discuss students’ other attributes and contributions.

It has become increasingly important for medical education programs to demonstrate the competence of their trainees beyond standardized exams so that they deliver high-value, cost-conscious, and safe patient care when practicing independently. Like Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) milestones for residencies, the Entrustable Professional Activity (EPA) framework could provide a common language for conveying students’ abilities across the continuum of medical education. While there are still limitations to the EPA model, they show promise to fulfill the Ottawa Criteria for good assessment: validity or coherence, reproducibility or consistency, equivalence with other assessment approaches, feasibility, acceptability, and a consideration of the educational effect and/or the catalytic effect on learning.1,2

The Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE) is ranked among the most important academic factors considered by primary care residency directors in the applicant selection process, alongside United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 and 2 scores, COMLEX 1 and 2 scores, and previous board failures.3,4 The MSPE is intended to provide residency program directors an honest and objective summary of a student’s salient experiences, attributes, and academic performance.5 While this is the aim, there is still much work to be done in optimizing the MSPE to facilitate the undergraduate medical education (UME)- graduate medical education (GME) transition.6-8

To the knowledge of the authors, no mixed-methods studies exist exploring primary care residency directors’ opinions on the application, and in particular, the MSPE, and how well it serves as a vehicle to make decisions to invite students for an interview. We explored which EPA skills were valued most in candidates, as these answers may help undergraduate medical education (UME) faculty and students construct the strongest primary care application, and more broadly, inform the future format of the MSPE.

Participants

The sample included PDs of any accredited (allopathic or osteopathic) primary care residency in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, or medicine-pediatrics with contact information available in the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Residency & Fellowship Database (FRIEDA).9 This study received approval by the Penn State University Institutional Review Board prior to recruitment (study #19263). We sent an email invitation to participate to a total of 1,566 potential participants. We sent three reminder emails were sent within the 2-week study time frame.

Procedures

We invited PDs to participate in the survey online using REDCap.10 The survey contained 5-point Likert scale questions ranging from 1 (“not important”) to 5 (“extremely important”) to assess the perceived importance of student skills (eg, note writing, oral presentations, etc) and application components (eg, USMLE scores, academic rank, etc) when considering the selection of a residency program candidate.11 Open-ended questions asked about additional candidate attributes and other factors taken into consideration during applicant selection, perceived strengths and limitations of the MSPE, and other additional comments. Demographics related to the participants and their programs were also obtained.

We converted Likert-scale responses for factors important to the MSPE into binary categories (yes: very or extremely important; no: not or slightly important and important). “Important” responses were added to the “no” category due to low responses for not/slightly important. We used SAS v.9.412 to derive descriptive statistics. We excluded incomplete responses from analysis.

Qualitative analysis of open-ended responses was performed using inductive thematic analysis by authors J.P. and Z.N.13,14 We created a codebook prior to individual coding, followed by collaborative review to reach 100% agreement on final codes and themes.15

Quantitative

We attained 249 responses (response rate=15.9%). Participant demographics are shown in Table 1.

In terms of student skills valued by program directors in primary care, the majority identified patient communication (83.6%) and teamwork (81.9%) as most important (Figure 1). The most valued application components were being a graduate of a US medical school in the past 3 years (73.1%), no failures on board exams (58.2%), and MSPEs (54.8%; Figure 2).

Qualitative

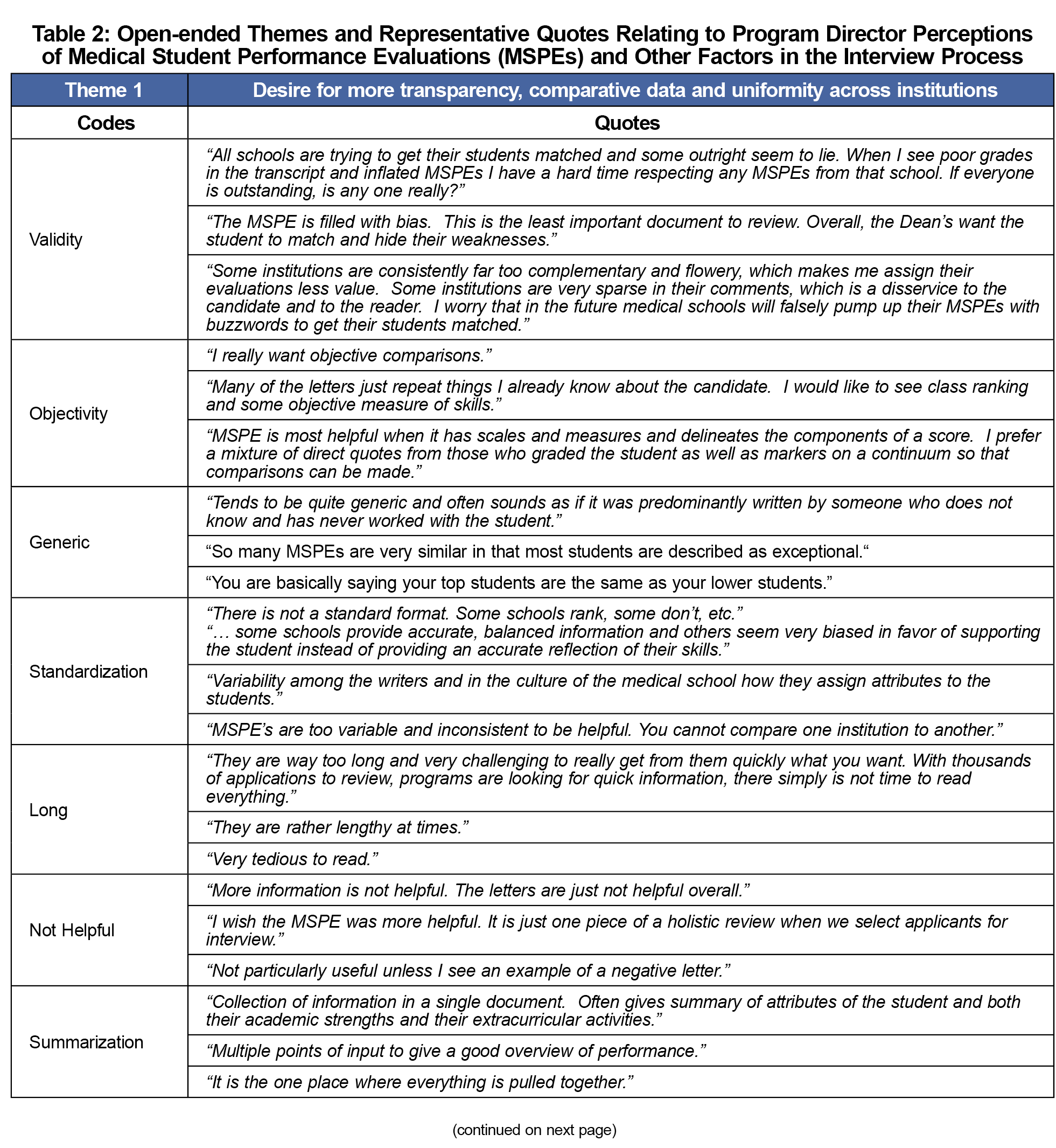

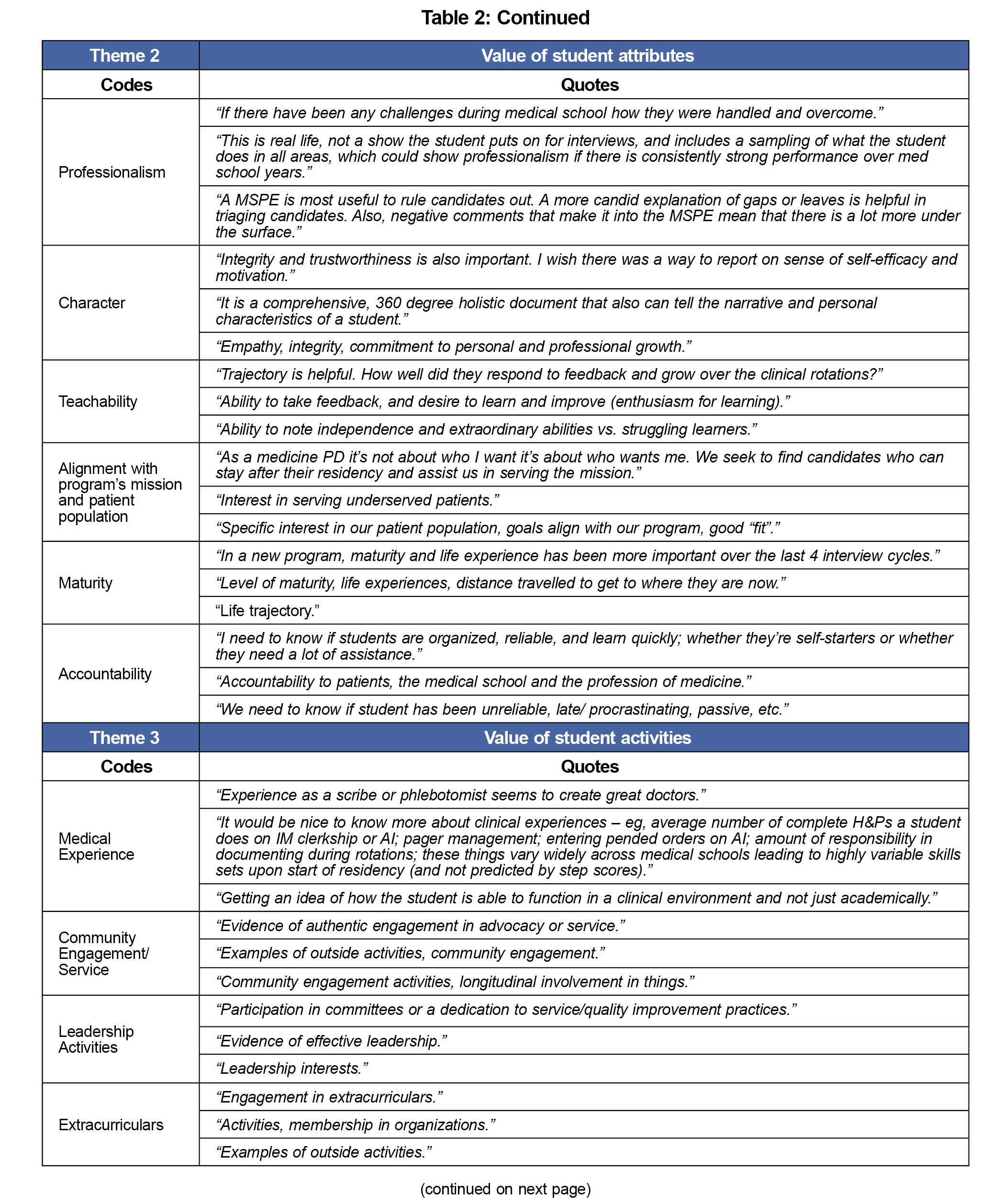

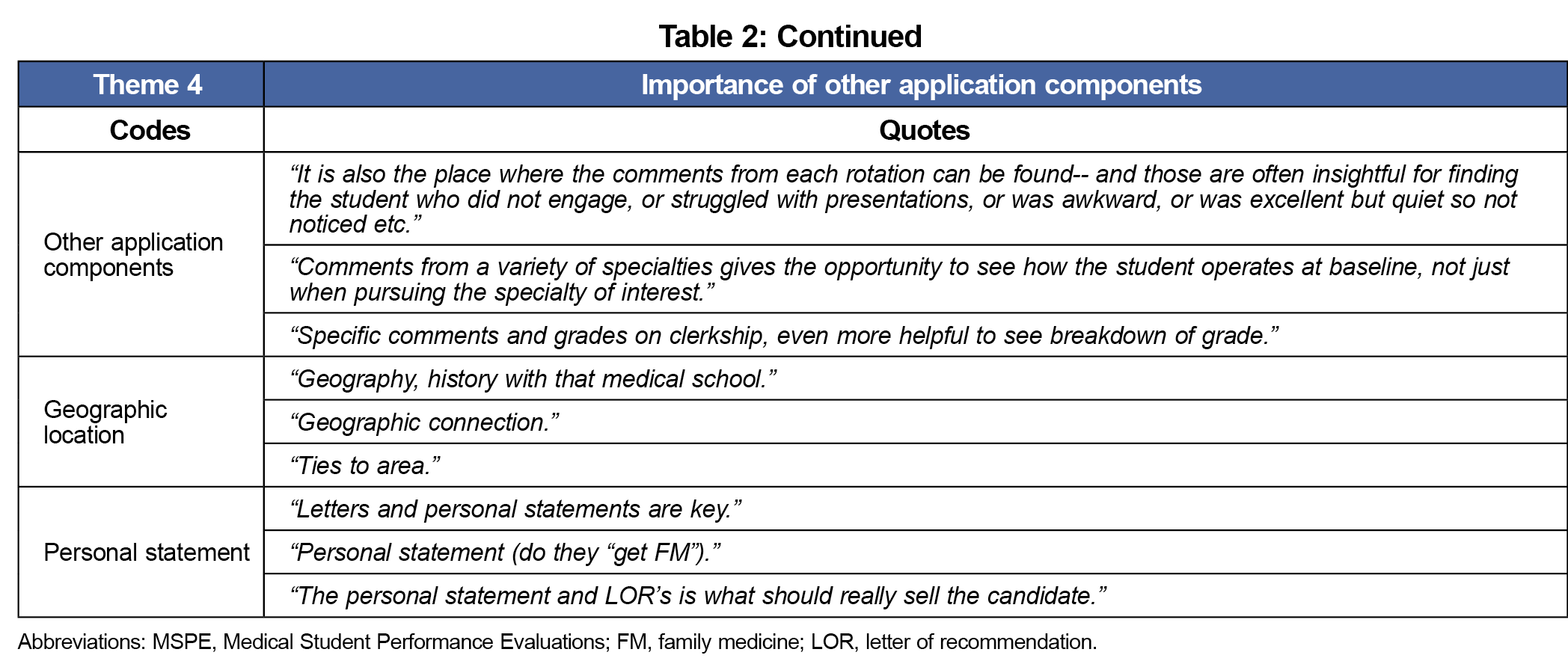

Open-ended responses (n=678) yielded four main themes related to MSPE limitations (n=193) and advantages (n=193), attributes most desired in a residency candidate (n=117), other factors considered for interview (n=104), and other additional comments (n=73). See Table 2 for representative quotes.

Theme 1: Desire for More Transparency, Comparative Data and Uniformity Across Institutions

Program directors found the MSPE to be very limited as a discriminator for applicant selection. Themes around the validity, objectivity, lack of standardization and general nature of MSPEs were identified as the most significant limitations.

Theme 2: Value of Student Attributes

Many PDs noted the importance of student attributes such as professionalism, accountability, and teachability when considering program candidates.

Theme 3: Value of Student Activities

PDs also noted the importance of student activities during their medical education, such as community engagement and service, leadership activities, and medical experience.

Theme 4: Importance of Other Application Components

Other application components were also valued by PDs, especially the personal statement, comments from rotations, and objective data such as Step 2 exam scores.

Among primary care PD respondents, high value was placed on the MSPE, previous board failures, and Step 2 scores as tools to aid in resident selection, in accordance to 2021 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) data, with the notable exception of Step 1 scores.16 This difference is not unexpected, as the most recent NRMP data was released prior to the shift of Step 1 to pass-fail scoring.

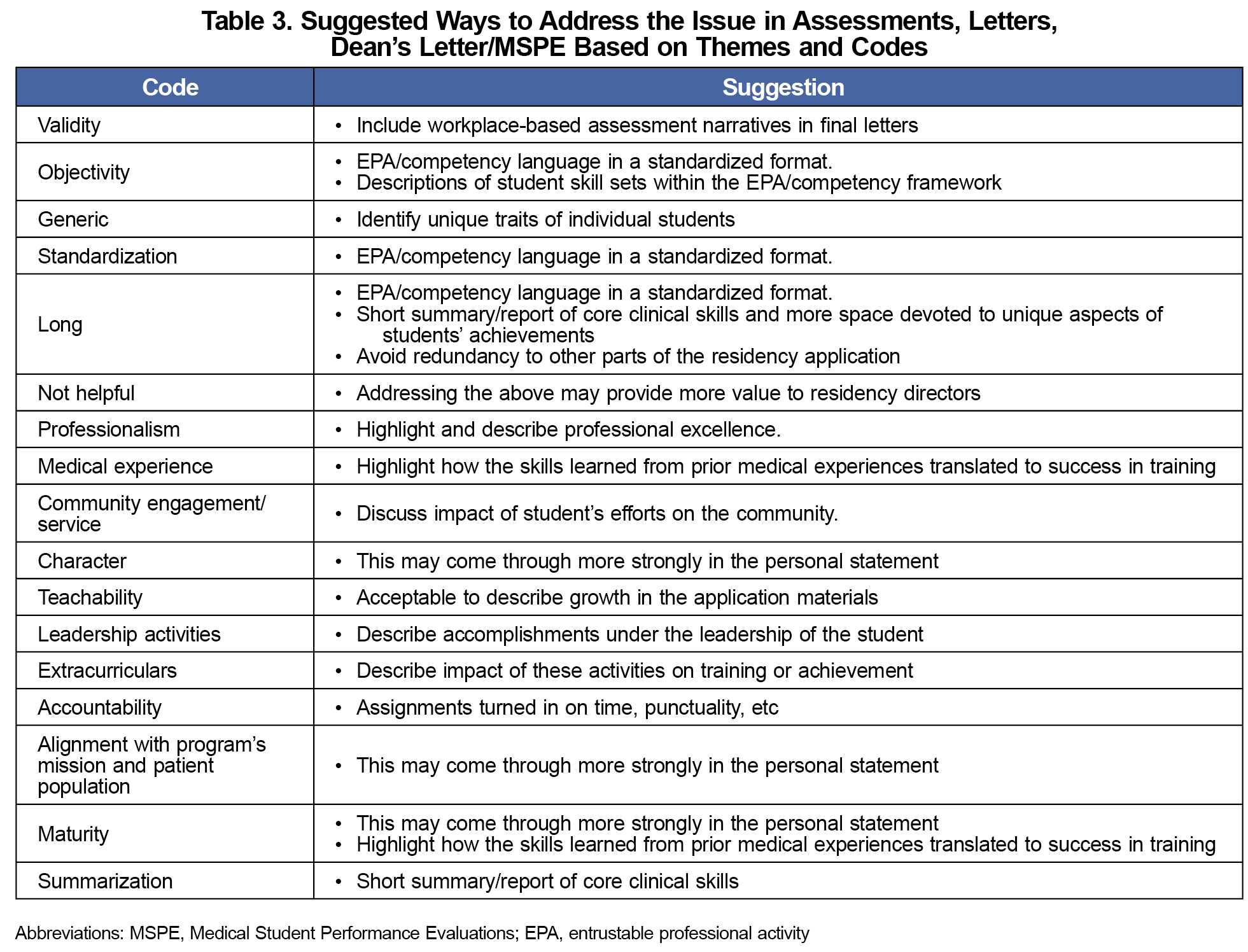

While many issues with MSPEs were identified, the most commonly-noted themes were around validity, objectivity, standardization, length, and the general nature of the document. Given a desire for more standardization and objectivity, using the common language of the published Association of American Medical Colleges EPAs may prove a useful, common frame of reference. We propose that the MSPE could be improved by discussing a student’s attainment of the core skills detailed in the EPAs. Schools could report how these were measured (eg, observed structured clinical encounter vs workplace-based assessment) and if competency committees were involved in reviewing the student data to improve transparency.

For primary care specialties, particular attention could be paid to the areas of patient communication (embedded in EPA 1- Gather a History and Perform a Physical Examination and EPA 11- Obtain Informed Consent for Tests and/or Procedures), teamwork (EPA 8- Give or Receive a Patient Handover to Transition Care Responsibility and EPA 9- Collaborate as a Member of an Interprofessional Team), and critical thinking (EPA 2- Prioritize a Differential Diagnosis Following a Clinical Encounter, EPA 3- Recommend and Interpret Common Diagnostic and Screening Tests and EPA 4- Enter and Discuss Orders and Prescriptions).

Program director respondents also place a high value on prior medical experience, leadership, and community service activities, as well as the congruence of the student’s interests with the program’s mission. While these aspects are likely found in other portions of the application, highlighting their impact on the school and community may improve the MSPE’s value to residency directors. Schools might also spend more time discussing the individual qualities of the student, specifically, professionalism, accountability, and character.

Though the four major areas of the country were evenly represented, respondents largely represented family medicine and there was a low number of respondents overall, making this the greatest limitation to generalizing these results.

Table 3 lists potential strategies for addressing the MSPE issues raised in this study. More research needs to be done to explore these strategies, as revisions to the MSPE incorporating these suggested changes may be beneficial to students and residency programs on a national level.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Erik Lehman, MS, research data analyst at Penn State College of Medicine, for his assistance with the statistical analysis of the results.

Presentations: This research was presented as an oral presentation at the 2023 STFM Conference on Medical Student Education in New Orleans, Louisiana, January 26-29, 2023.

References

- Lomis K, Amiel JM, Ryan MS, et al; AAMC Core EPAs for Entering Residency Pilot Team. Implementing an entrustable professional activities framework in undergraduate medical education: early lessons from the AAMC core entrustable professional activities for entering residency pilot. Acad Med. 2017;92(6):765-770. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001543

- Meyer EG, Chen HC, Uijtdehaage S, Durning SJ, Maggio LA. Scoping review of entrustable professional activities in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):1040-1049. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002735

- National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Match Data & Report Archives. 1984-2021. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/match-data-analytics/archives/

- National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Residency Data & Reports. 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/match-data-analytics/residency-data-reports/

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE). Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/gsa/medical-student-performance-evaluation

- Andolsek KM. Improving the medical student performance evaluation to facilitate resident selection. Acad Med. 2016;91(11):1475-1479. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001386

- Hauer KE, Giang D, Kapp ME, Sterling R. Standardization in the MSPE: key tensions for learners, schools, and residency programs. Acad Med. 2021;96(1):44-49. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003290

- Tisdale RL, Filsoof AR, Singhal S, et al. A Retrospective Analysis of Medical Student Performance Evaluations, 2014-2020: recommend with Reservations. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(9):2217-2223. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07502-8

- American Medical Association (AMA). The AMA Residency & Fellowship Database. 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://freida.ama-assn.org/.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Dambro A. EPA framework in the residency application process survey.STFM Resource Library; 2022. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/epa-framework-in-the-residency-appl?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

- Base SAS 9.4 procedures guide.SAS Institute; 2015.

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Sage; 1998.

- Chapman A. MH-J of the R, 2015 undefined. Qualitative research in healthcare: an introduction to grounded theory using thematic analysis. eprints. gla. ac. uk. 2015.

- Dambro A. Sub themes developed from open-ended questions.STFM Resource Library; 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023.

- National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Results and Data 2021 Main Residency Match. 2021. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/MRM-Results_and-Data_2021.pdf

There are no comments for this article.