Background and Objectives: This study evaluated the effectiveness of a short, skills-based workshop, called a Letter-Writing Lunch (LWL), in teaching advocacy to medical students.

Methods: We assessed political activity, political efficacy, civic responsibility, and skill mastery via pre-, post-, and 6-month follow-up surveys. Via semistructured follow-up interviews, we explored how the intervention affected the participant’s view of advocacy.

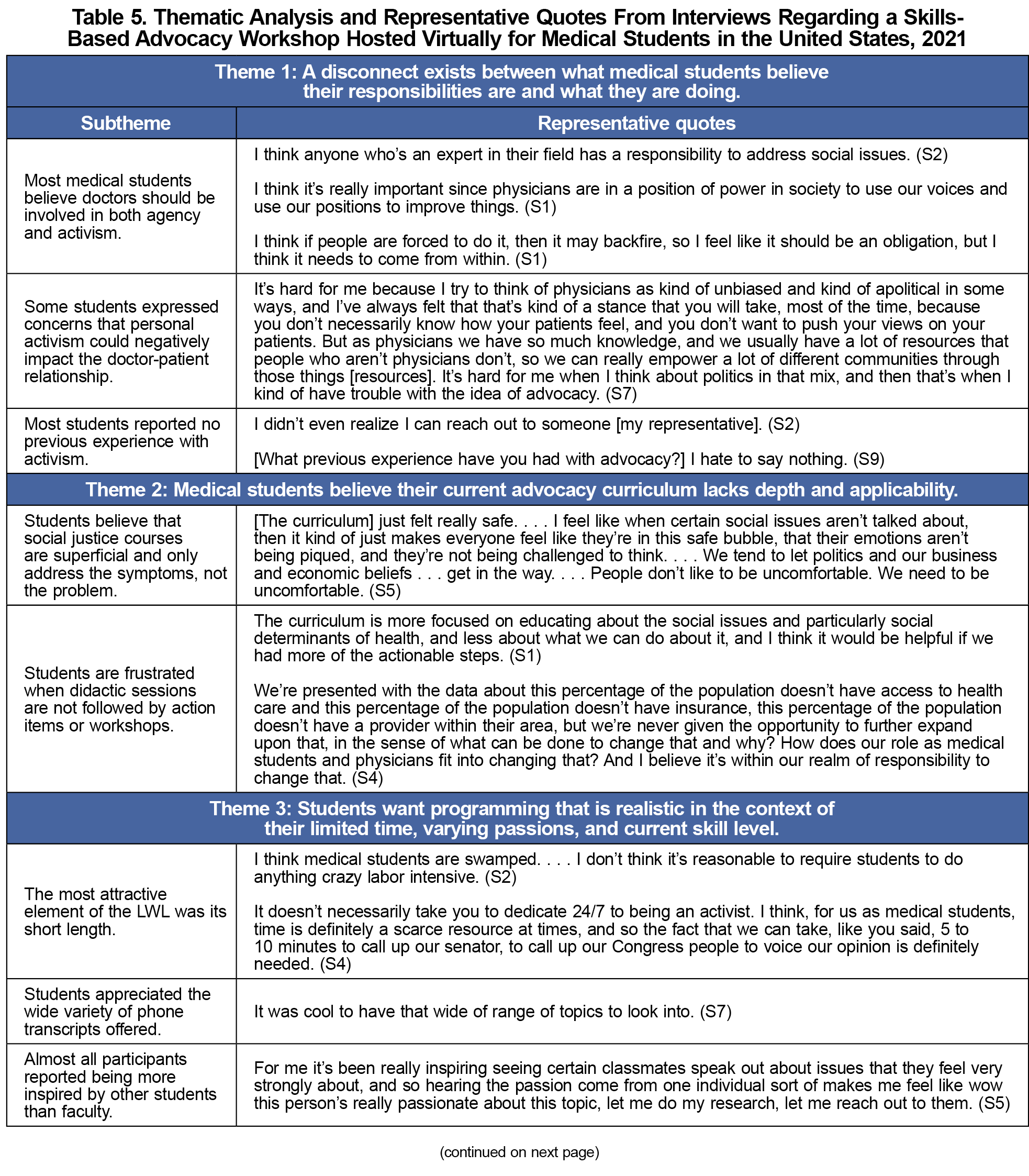

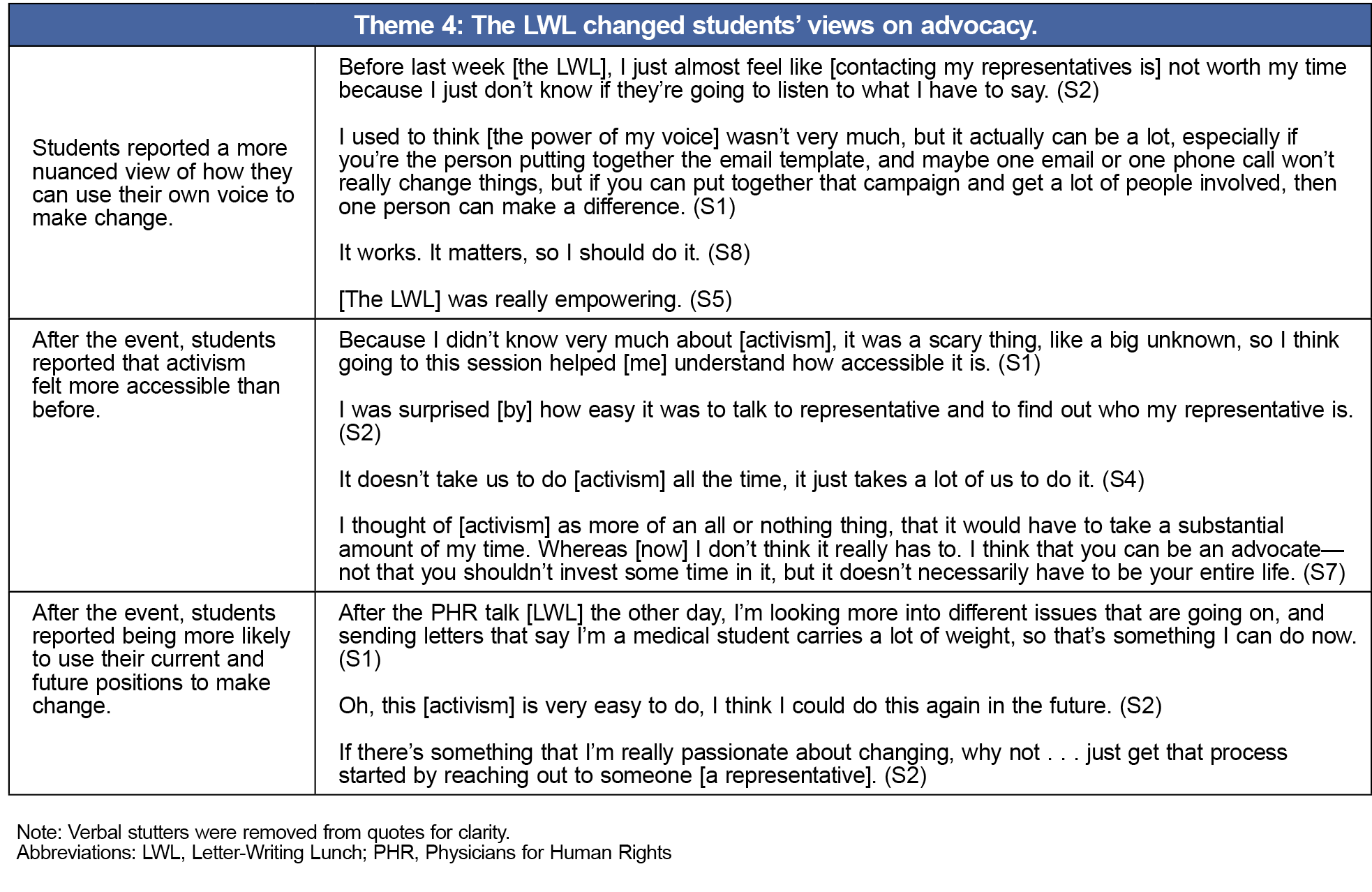

Results: Students mastered identifying and contacting their representatives. Participants’ political activity scores demonstrated little to no political activity at baseline and were unchanged at 6 months. Political efficacy scores increased after the event (t[53]=8.5, P<.001), and they remained elevated at 6 months (t[25]=2.1, P=.047). Feelings of civic responsibility significantly increased from the pre- to postsurvey (z=482.5, P<.001), but returned to baseline by 6 months. Four themes emerged from the follow-up interviews: (a) A disconnect exists between what medical students believe their responsibilities are and what they are doing; (b) medical students believe their current advocacy curriculum lacks depth and applicability; (c) students want programming that is realistic in the context of their limited time, varying passions, and current skill level; and (d) the LWL changed students’ views on advocacy.

Conclusions: Current skills-based education is time-intensive and fails to engage students who are not already committed to developing advocacy skills. Keeping the LWL short in length successfully targeted students with little previous advocacy experience. The event increased political efficacy and civic responsibility while making advocacy appear more accessible. The LWL is an effective and efficient way to teach advocacy to medical students.

A lack of applicable skills has been identified as a key barrier to engaging in advocacy work, but no documentation in the medical education literature concerns skills-based advocacy education that reaches all students.1 Current skills-based education generally is elective and ranges from a 3-hour to 4-year commitment; therefore, participants typically are self-selected from students already interested in advocacy.1-7 Required courses reach all students but are unlikely to include skill-building education (5.3% of required vs 43.3% of elective).8-12

In response, we piloted a short educational workshop, called a Letter-Writing Lunch (LWL), designed to teach an advocacy microskill to students with little advocacy experience. During the virtual event, students practiced identifying and calling their congressional representative and senators with prewritten templates. We hypothesized that the intervention would increase political efficacy, civic responsibility, and skill mastery among participants. Political efficacy is the belief that one can influence the government and that the government is responsive to one’s concerns. Civic responsibility is the duty of each citizen to act for the betterment of society.

Study Design

Our study was a mixed-methods investigation, including three cross-sectional surveys via Qualtrics (Qualtrics, LLC; before, immediately after, and 6 months after the intervention) and qualitative interviews. Medical students connected to a national advocacy organization used emails and social media to recruit participants from 12 US MD- and DO-granting medical schools.13 Survey participants were entered into $25 raffles.

In the absence of established methods to evaluate competency in health advocacy,14 we combined validated survey instruments from the social sciences. We assessed political efficacy, civic responsibility, and current political involvement via the Political Efficacy Short Scale, Faith and Civic Engagement scale, and Social Issues Advocacy Scale, respectively.15-17 We assessed skill mastery by a participant’s ability to name their federal representatives.

To target students who were unfamiliar with advocacy, we contacted the survey respondents with the lowest 20% of combined initial political efficacy and civic responsibility scores for a 30-minute semistructured follow-up interview. To interview those most affected by the event, we also contacted the five participants with the largest absolute change in political efficacy and civic responsibility scores. We solicited interviews until the data reached saturation. Interviews explored how the intervention affected the participant’s view of advocacy and how the LWL could be incorporated into medical school curricula. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Interviewees were compensated $15.

We compiled data from two iterations of the LWL (May and October 2021). Our study was exempted from review by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The inclusion criteria were being over the age of 18, English speaking, and a current medical student in the United States. Incomplete survey responses were excluded. In the case of duplicate responses, only the first was included.

Data Analysis

All statistical tests were performed using JMP Pro version 16.0.0 for Mac (SAS Institute) and were two-tailed.

Likert scale responses were summed to create a total score for political activity and political efficacy at each time point, which were then compared by paired t tests. The total score for civic responsibility and perceived skill difficulty were compared with a Wilcoxon signed rank test.

To evaluate skill mastery, we asked students to report the zip code in which they were eligible to vote and their congressional representatives and senators. Responses were graded for correctness. A McNemar test was used to compare the pre- and postsurvey responses. Data from participants who were not eligible or registered to vote were excluded. Participants also self-reported whether they knew how to contact their representatives, and responses were evaluated with a McNemar test.

Interview analysis was conducted by one reviewer trained in the principles of grounded theory.18 The first few interview transcripts were manually coded via line-by-line coding. Initial codes either were in the participant’s own words (in vivo codes) or a gerund. After prevalent themes emerged from the data, focused coding of common or salient ideas was completed for the remaining transcripts. To explore the connections between themes, memos were compiled as data were analyzed.

Survey Results

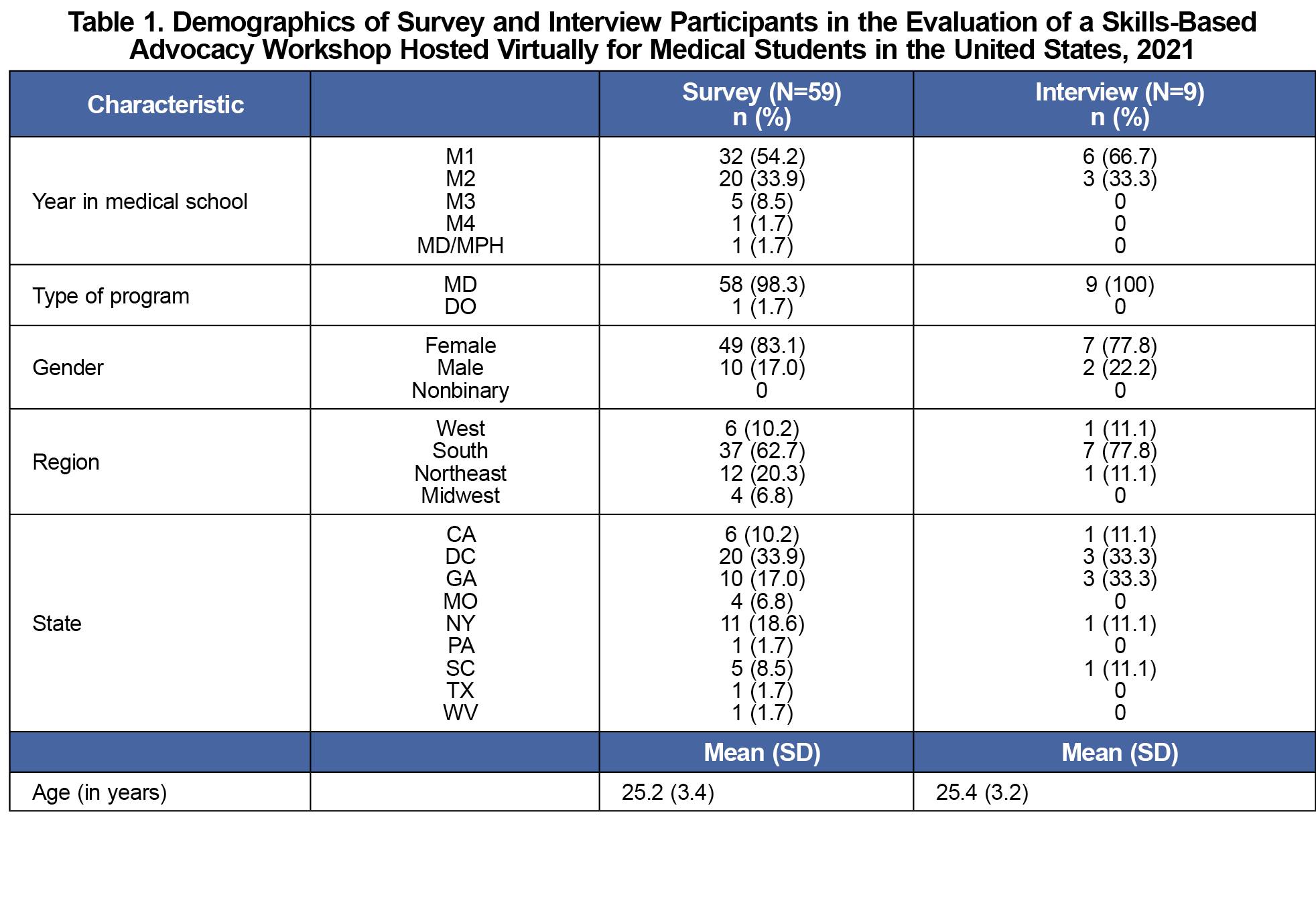

Of 167 students registered to attend the event, 80 (47.9%) completed the presurvey, 59 (35.3%) completed the postsurvey, and 27 (16.2%) completed the 6-month follow-up. The participants were from 14 different schools, mostly in the South, and were largely first- or second-year students (Table 1).

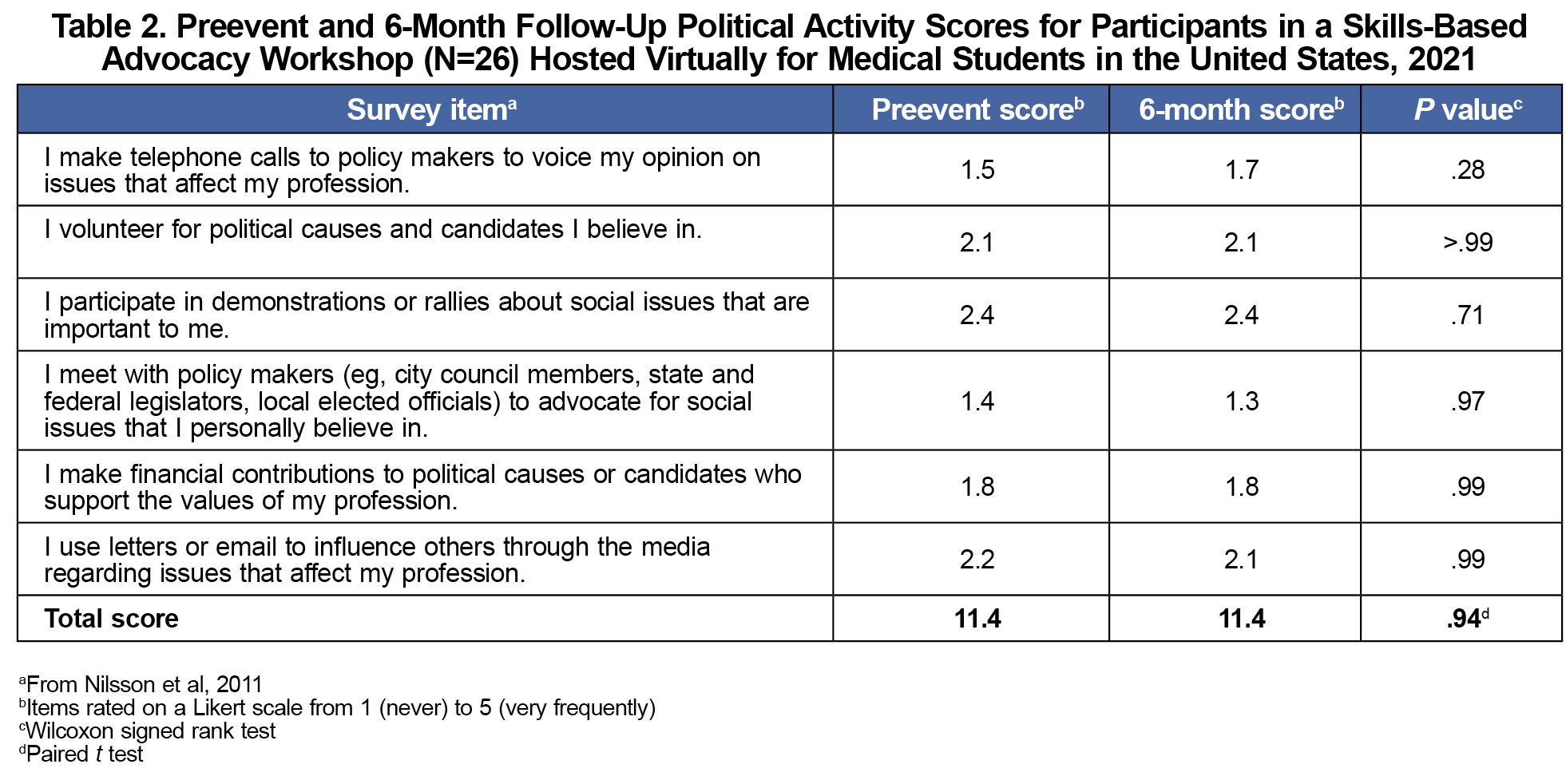

The average pre-event summed political activity score was 11.4 (SD 3.5; Table 2). This is equivalent to being “rarely” or “occasionally” involved in political activity. No statistical difference in political activity scores existed at 6 months (P=.94).

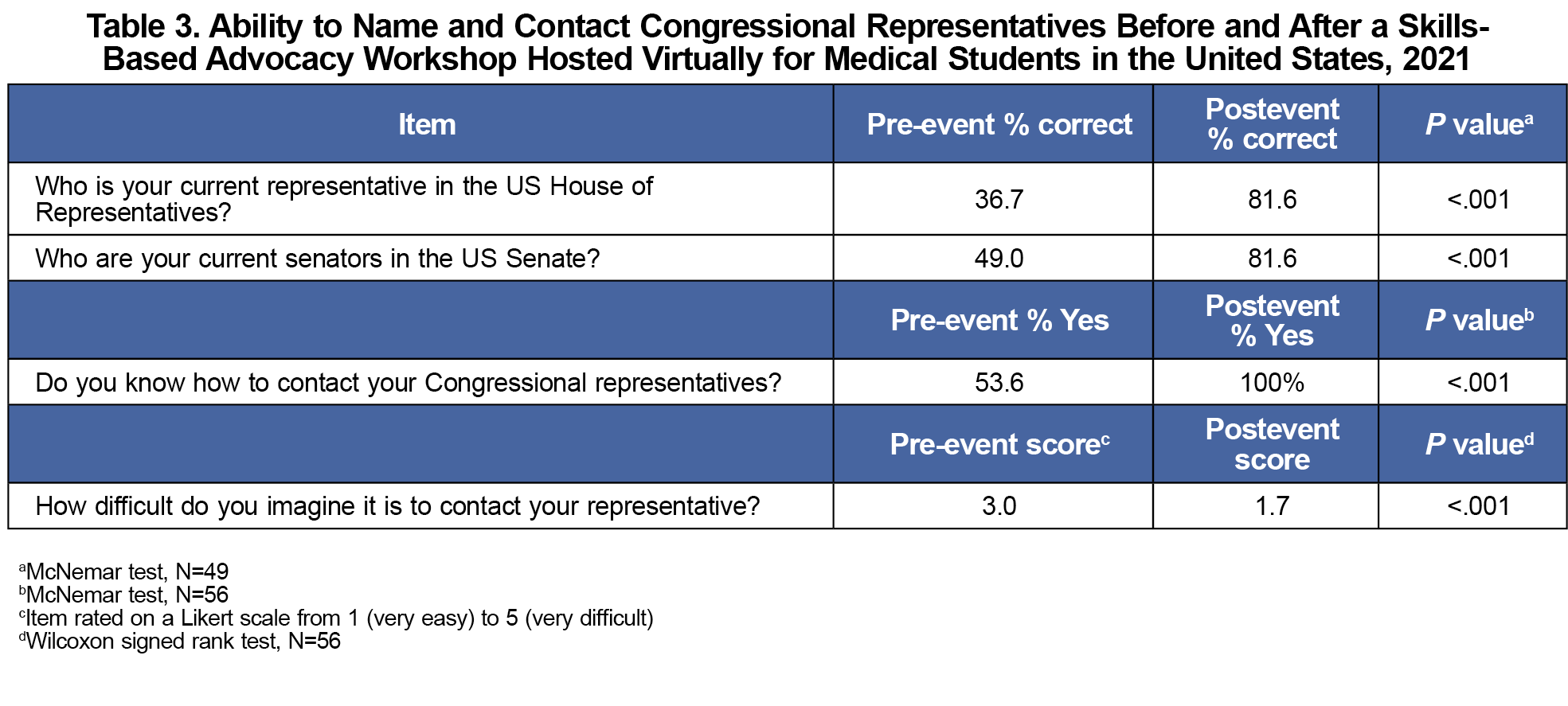

Before the LWL, 36.7% of participants correctly identified their representative, and 49.0% of participants correctly identified both of their senators (Table 3). Afterward, 81.6% were correct (P<.001) for both questions. After the event, participants also showed a statistically significant decrease in perceived difficulty of the skill (z=–759, P<.001).

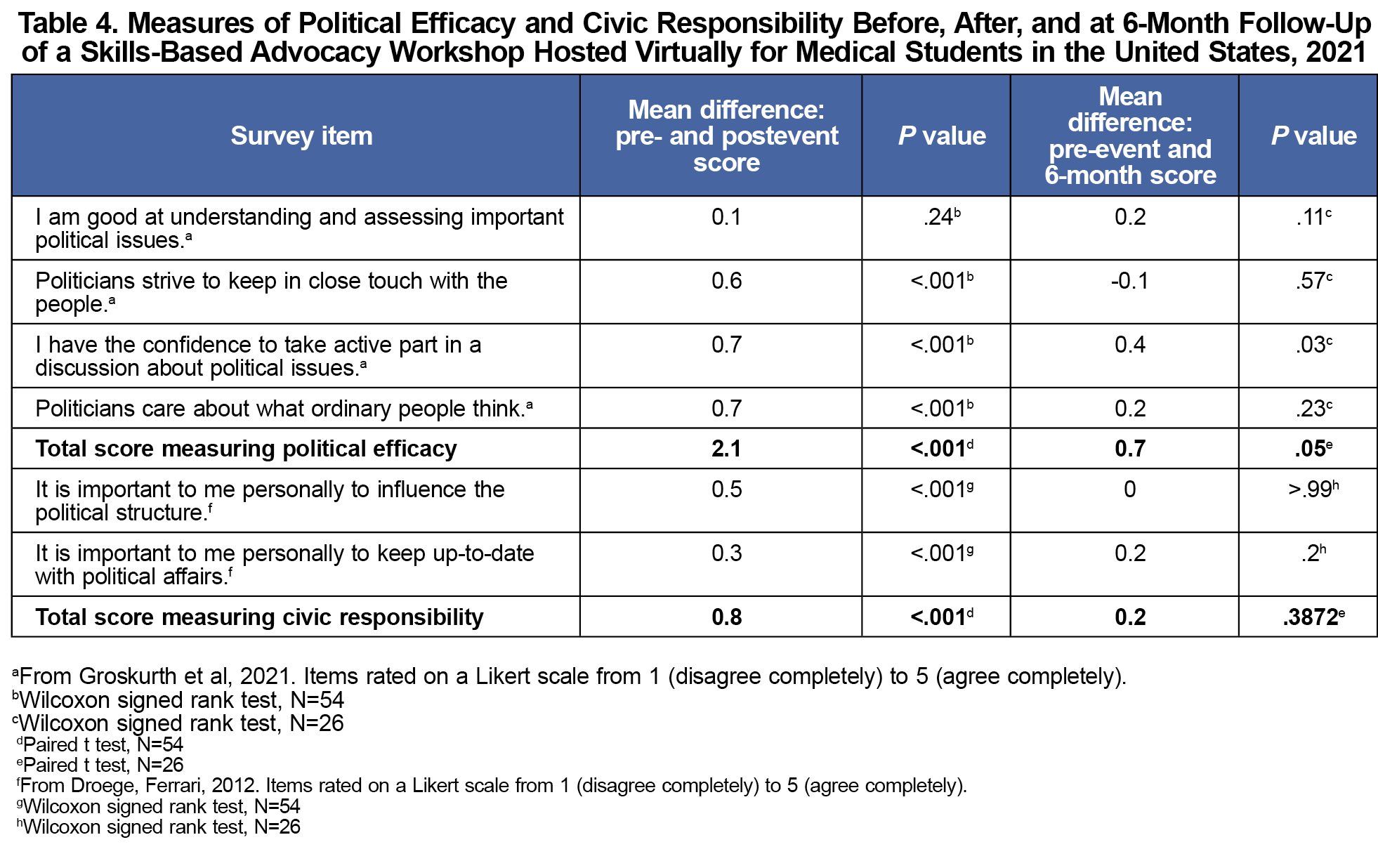

A statistically significant increase in political efficacy was evident after the event (t[53]=8.5, P<.001; Table 4). Political efficacy was lower at 6 months compared to immediately postevent, but the increase from baseline was sustained (t[25]=2.1, P=.047). Civic responsibility significantly increased from pre- to postsurvey (z=482.5, P<.001), but returned to baseline by 6 months (Table 4).

Interview Results

We interviewed nine students (Table 1), resulting in the following four themes. Representative quotes can be found in Table 5.

Theme 1: A disconnect exists between what medical students believe their responsibilities are and what they are doing.

Despite most students believing that advocacy is a responsibility of physicians, only 2/9 (22.2%) reported previous experience with advocacy. Students primarily attributed their inaction to a lack of confidence and knowledge of practical skills.

Theme 2: Medical students believe their current advocacy curriculum lacks depth and applicability.

All students reported learning about health disparities within the medical school curriculum; however, they felt it was superficial. When schools did address the power structures that perpetuate disparities, all students reported that only didactic methods were used. Students shared that when these didactic sessions are not followed by action items or skills training, they are left feeling frustrated or hopeless. Participants repeatedly emphasized that they wanted actionable steps incorporated into social justice lectures.

Theme 3: Students want programming that is realistic in the context of their limited time, varying passions, and current skill level.

Students identified being accessible and practical as the most attractive elements of the LWL. They advised that all workshops be kept very short, especially if trying to appeal to students who are ambivalent toward advocacy. Furthermore, students appreciated the variety of advocacy templates offered and being able to easily find an issue that aligned with their values. Finally, interviewees reported being inspired by other students. They said that watching other students engage in advocacy empowered them to believe that their current skills and abilities were enough to become involved themselves.

Theme 4: The LWL changed students’ views on advocacy.

Most participants reported that before the LWL, they believed that one individual does not have any power to make change in society. They felt as if they did not have the time nor the skills to engage in meaningful advocacy. After the event, participants had a more positive and nuanced view of their political efficacy. They agreed that one phone call was not very powerful, but when combined with the collective actions of hundreds of people, they can generate real change. Additionally, students reported wanting to get more involved and being more likely to use their current and future positions to make change. Finally, students reported that the LWL provided accountability and a call to action.

The LWL facilitators successfully taught an advocacy microskill to medical students while increasing feelings of civic responsibility and political efficacy. This result indicates that not only did students feel an increased responsibility to address the needs of their community, but they also felt more capable of doing so. Notably, the increase in political efficacy was sustained, albeit smaller, at 6 months, demonstrating that the LWL may have long-lasting effects on students’ beliefs about advocacy.

Our qualitative study found that a brief educational intervention made advocacy feel accessible and that students believed skills-based training is a necessary component of advocacy curricula. Before the LWL, our participants were involved in little, if any, advocacy, despite agreeing that it is an obligation of individual physicians. The LWL broke down perceived barriers, such as time and skill, and students began to believe that they themselves could initiate societal change. Additionally, our respondents aligned with previous literature stating that when students are taught about health disparities but are not given actionable responses, the students are left frustrated.4,5,19 Echoing other studies,20-23 our respondents emphasized that they wanted to learn actionable skills to complement didactic education.

This is the first study to involve students from multiple medical schools (14), including each geographic region of the United States, and thus may be more generalizable than previous studies at individual institutions.1-4,6,9-11 This study also successfully targeted medical students with limited advocacy experience (Table 2), and the LWL met the need for meaningful skills education among these students.

This study was limited by the small sample size, particularly at the 6-month follow-up, and a reliance on self-assessment. However, the self-reported findings were strengthened by supporting qualitative data in our mixed-methods approach. Finally, the event was promoted by an advocacy organization; therefore, these self-selected participants are not likely a true representation of the ambivalent or opposed student population. Regardless, this pilot study suggested that the LWL may be able to bridge beliefs about the importance of advocacy with tangible action. We hope to use this pilot toward the creation of an advocacy toolkit, a collection of skills empowering students to advocate on behalf of their patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Kate Sugarman for sharing her expertise at the Letter-Writing Lunch event and inspiring so many students. They also would like to thank Ms Xue Geng for providing biostatistical support during our data analysis. They also would like to thank Ms Jina Lee, Ms Anahita Sattari, Ms Avi Borad, Mr Ahmed Zanabli, Ms Sameena Hameed, and Mr Joseph Karam for contributing phone and email transcripts for the events. Finally, they would like to thank the Physicians for Human Rights Student Advisory Board and the many, many chapters that helped advertise these events at medical schools across the country.

Funding/Support

The Georgetown Chapter of Physicians for Human Rights graciously provided funding for participant compensation.

Ethical Approval

This study was exempted from review by the Institutional Review Board of Georgetown University School of Medicine on May 17, 2021. Reference #00003862.

References

- Hayman K, Wen M, Khan F, Mann T, Pinto AD, Ng SL. What knowledge is needed? Teaching undergraduate medical students to “go upstream” and advocate on social determinants of health. Can Med Educ J. 2020;11(1):e57-e61. doi:10.36834/cmej.58424

- Girard VW, Moore ES, Kessler LP, Perry D, Cannon Y. An interprofessional approach to teaching advocacy skills: lessons from an academic medical–legal partnership. J Leg Med. 2020;40(2):265-278. doi:10.1080/01947648.2020.1819485

- Long JA, Lee RS, Federico S, Battaglia C, Wong S, Earnest M. Developing leadership and advocacy skills in medical students through service learning. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17(4):369-372. doi:10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182140c47

- Gonzalez CM, Fox AD, Marantz PR. The evolution of an elective in health disparities and advocacy: description of instructional strategies and program evaluation. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1,636-1,640. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000850

- Sola O, Kothari P, Mason HRC, Onumah CM, Sánchez JP. The crossroads of health policy and academic medicine: an early introduction to health policy skills to facilitate change. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10827. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10827

- Vela MB, Kim KE, Tang H, Chin MH. Innovative health care disparities curriculum for incoming medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1,028-1,032. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0584-2

- Cha SS, Ross JS, Lurie P, Sacajiu G. Description of a research-based health activism curriculum for medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):1,325-1,328. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00608.x

- Brender TD, Plinke W, Arora VM, Zhu JM. Prevalence and characteristics of advocacy curricula in U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2021;96(11):1,586-1,591. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004173

- Press VG, Fritz CDL, Vela MB. First year medical student attitudes about advocacy in medicine across multiple fields of discipline: analysis of reflective essays. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(4):556-564. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0105-z

- Cole McGrew M, Wayne S, Solan B, Snyder T, Ferguson C, Kalishman S. Health policy and advocacy for New Mexico medical students in the family medicine clerkship. Fam Med. 2015;47(10):799-802. https://www.stfm.org/familymedicine/vol47issue10/McGrew799

- McIntosh S, Block RC, Kapsak G, Pearson TA. Training medical students in community health: a novel required fourth-year clerkship at the University of Rochester. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):357-364. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181668410

- Prunuske J, Chang L, Mishori R, Dobbie A, Morley CP. The extent and methods of public health instruction in family medicine clerkships. Fam Med. 2014;46(7):544-548.

- Physicians for Human Rights Student Program. PHR chapters. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.phrstudents.com/phr-chapters

- Hubinette M, Dobson S, Scott I, Sherbino J. Health advocacy. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):128-135. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1245853

- Groskurth K, Nießen D, Rammstedt B, Lechner CM. An English-language adaptation and validation of the political efficacy short scale (PESS). Meas Instrum Soc Sci. 2021;3(1):1. doi:10.1186/s42409-020-00018-z

- Droege JR, Ferrari JR. Toward a new measure for faith and civic engagement: exploring the structure of the FACE scale. Christ High Educ. 2012;11(3):146-157. doi:10.1080/15363751003780852

- Nilsson JE, Marszalek JM, Linnemeyer RM, Bahner AD, Misialek LH. Development and assessment of the social issues advocacy scale. Educ Psychol Meas. 2011;71(1):258-275. doi:10.1177/0013164410391581

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis.SAGE; 2006.

- Vela MB, Chin MH, Press VG. Advocacy training as a complement to instruction about health disparities. Acad Med. 2016;91(4):449. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001109

- Griffiths EP, Tong MS, Teherani A, Garg M. First year medical student perceptions of physician advocacy and advocacy as a core competency: A qualitative analysis. Med Teach. 2021;43(11):1,286-1,293. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2021.1935829

- Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: A path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med. 2018;93(1):25-30. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001689

- Gonzalez CM, Bussey-Jones J. Disparities education: what do students want? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 2):S102-S107. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1250-z

- Croft D, Jay SJ, Meslin EM, Gaffney MM, Odell JD. Perspective: is it time for advocacy training in medical education? Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1,165-1,170. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826232bc

There are no comments for this article.