Utah has experienced rapid population growth, principally among individuals from groups underrepresented in medicine (URiM).1,2 At the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine (SFESOM) at the University of Utah, these groups have been defined as Latinx (Hispanic or Latino), Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and women from all backgrounds. Utah is home to a growing Latinx population, eight tribal nations, and the highest percentage of Pacific Islanders in the continental United States (only Hawaii and Alaska have higher representation).3 More than 60,000 new Americans have come to Utah through refugee programs, with more than 120 languages represented.3

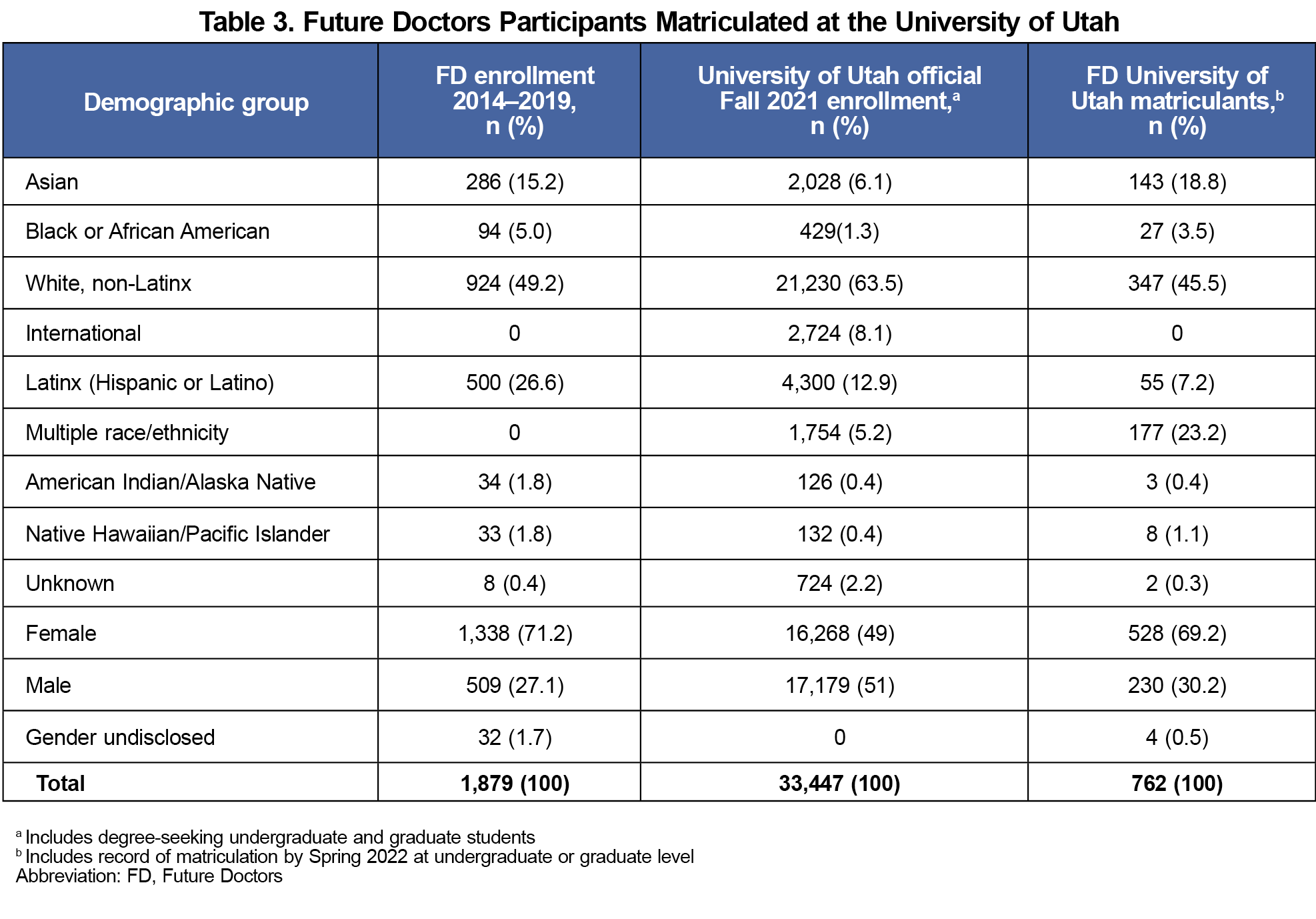

To increase the diversity of the physician workforce in Utah, SFESOM established and funded the Future Doctors (FD) program in 1998. FD is a precollege program designed for high school learners to promote academic preparedness and increase exposure to health careers. FD focuses on recruiting URiM students from local schools through partnerships with teachers and administrators. SFESOM employees visit classrooms and give presentations designed to encourage participation. FD students are recruited from groups of students less likely to attend college in the first 3 years after high school graduation.

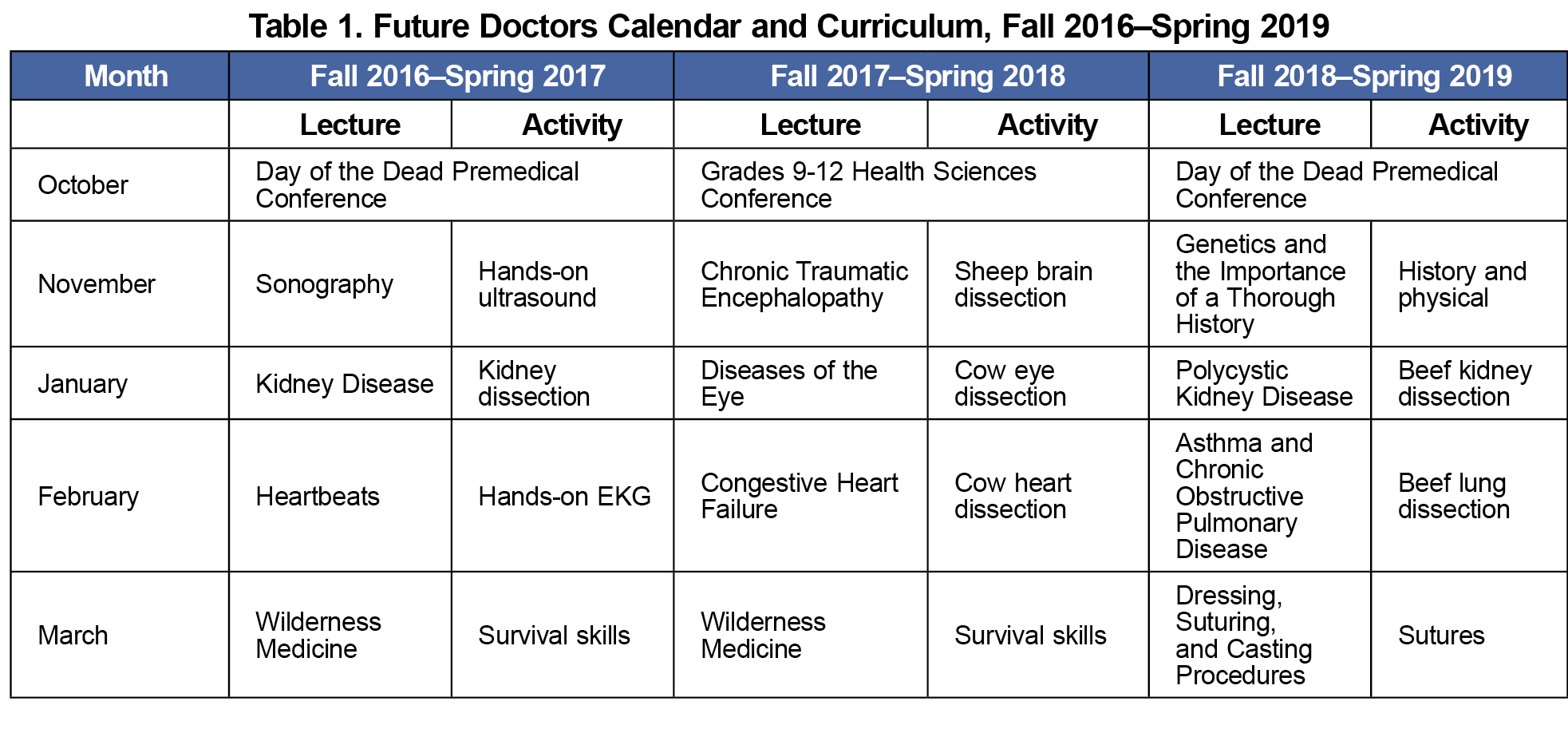

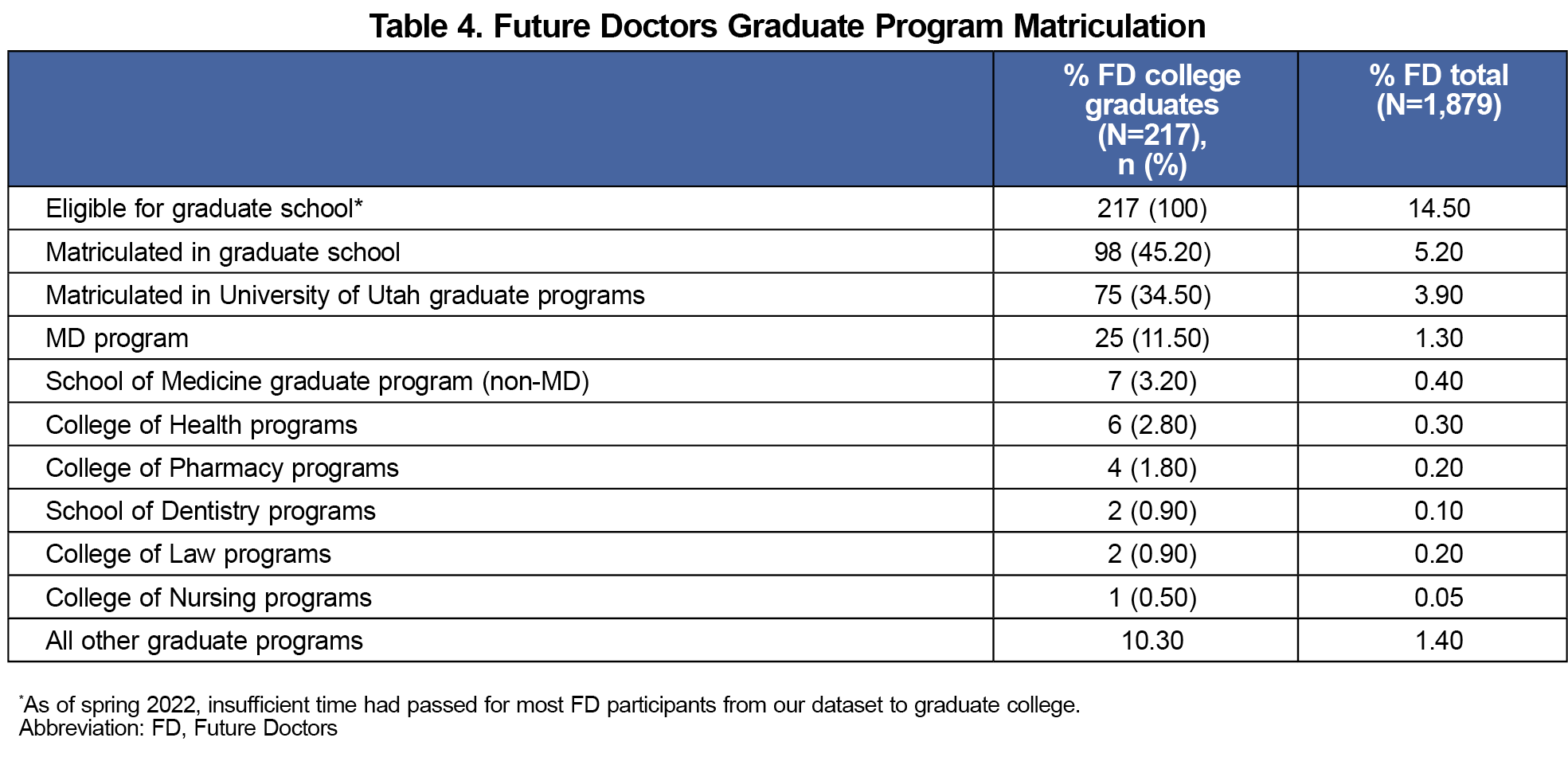

FD sessions, held monthly after school at the health sciences campus of the University of Utah, are organized by second-year medical students. Sessions consist of a faculty speaker with an hour-long presentation related to their specialty in medicine, followed by a short question and answer period. Medical students lead the activity and are the principal instructors for the hands-on portion of the curriculum. Table 1 illustrates the curriculum for three recent cycles of FD programming. We performed this study to evaluate the associations of FD students with graduate programs at the University of Utah.

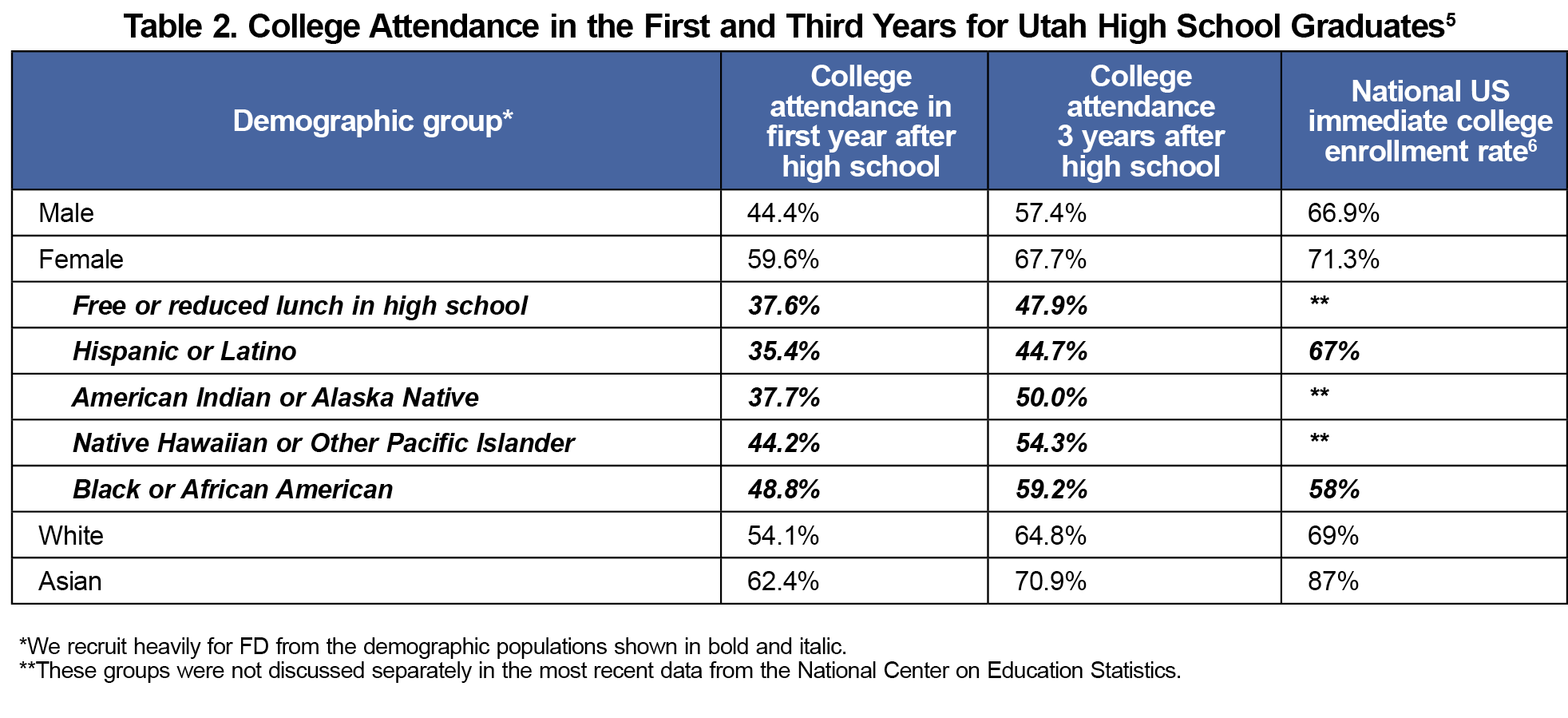

In Utah, relatively low numbers of students attend college in the first year after high school. Most Utah residents are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,4 and men and women in that faith often delay formal education to serve as missionaries in the first 2 years after high school. Even after 3 years, no population had more than 70% of their eligible students attending college (Table 2).5,6

As evidenced in the table, 52% to 66% of the target recruitment group do not attend college in the first year after high school in the state of Utah. Even 3 years after high school, 40% to 52% of the target group do not attend college.

There are no comments for this article.