Background and Objectives: In order to emphasize the role family medicine plays in providing robust primary care in functioning health care systems, we piloted a novel online curriculum for third-year medical students. Using a digital documentary and published articles as prompts, this flipped-classroom, discussion-based Philosophies of Family Medicine curriculum (POFM) highlighted concepts that have either emerged from or been embraced by family medicine (FM) over the past 5 decades. These concepts include the biopsychosocial model, the therapeutic importance of the doctor-patient relationship, and the unique nature of FM. The purpose of this mixed-methods pilot study was to assess the effectiveness of the curriculum and assist in its further development.

Methods: The intervention—POFM—consisted of five 1-hour, online discussion sessions with 12 small groups of students (N=64), distributed across seven clinical sites, during their month-long family medicine clerkship block rotations. Each session focused on one theme fundamental to the practice of FM. We collected qualitative data through verbal assessments elicited at the end of each session and written assessments at the end of the entire clerkship. We collected supplementary quantitative data via electronically distributed anonymous pre- and postintervention surveys.

Results: The study qualitatively and quantitatively demonstrated that POFM helped students understand philosophies fundamental to the practice of FM, improved their attitudes toward FM, and aided in their appreciation of FM as an essential element of a functioning health care system.

Conclusion: The results of this pilot study show effective integration of POFM into our FM clerkship. As POFM matures, we plan to expand its curricular role, further evaluate its influence, and use it to increase the academic footing of FM at our institution.

The discipline of family medicine (FM) grew out of a need to address specific concerns about the US health care system in the 1960s.1-3 These concerns included fragmentation of care, inequitable access to care, and the general lack of quality primary care services. Many of these concerns are still present. Unfortunately, FM educators may neglect to convey how family medicine education is integral to addressing these concerns. Moreover, we may miss opportunities to mold the professional identities of those students planning to enter FM and fail to inculcate the importance of FM in students planning to enter other fields.

In order to emphasize the key role FM plays in functioning health care systems, we piloted a novel curriculum for third-year students (M3s) on their month-long block FM clerkships. This Philosophies of Family Medicine curriculum (POFM) highlighted concepts that have either emerged from or been embraced by FM over several decades. We hypothesized that POFM would help students: (1) appreciate FM as an important contribution to quality medical care, (2) regard FM as a valued medical profession, and (3) develop an ethos of professional interdependency, the understanding that health care systems work best when health care professionals work together. The purpose of this study was to evaluate this curriculum in light of these hypotheses and assist in its further development.

Intervention

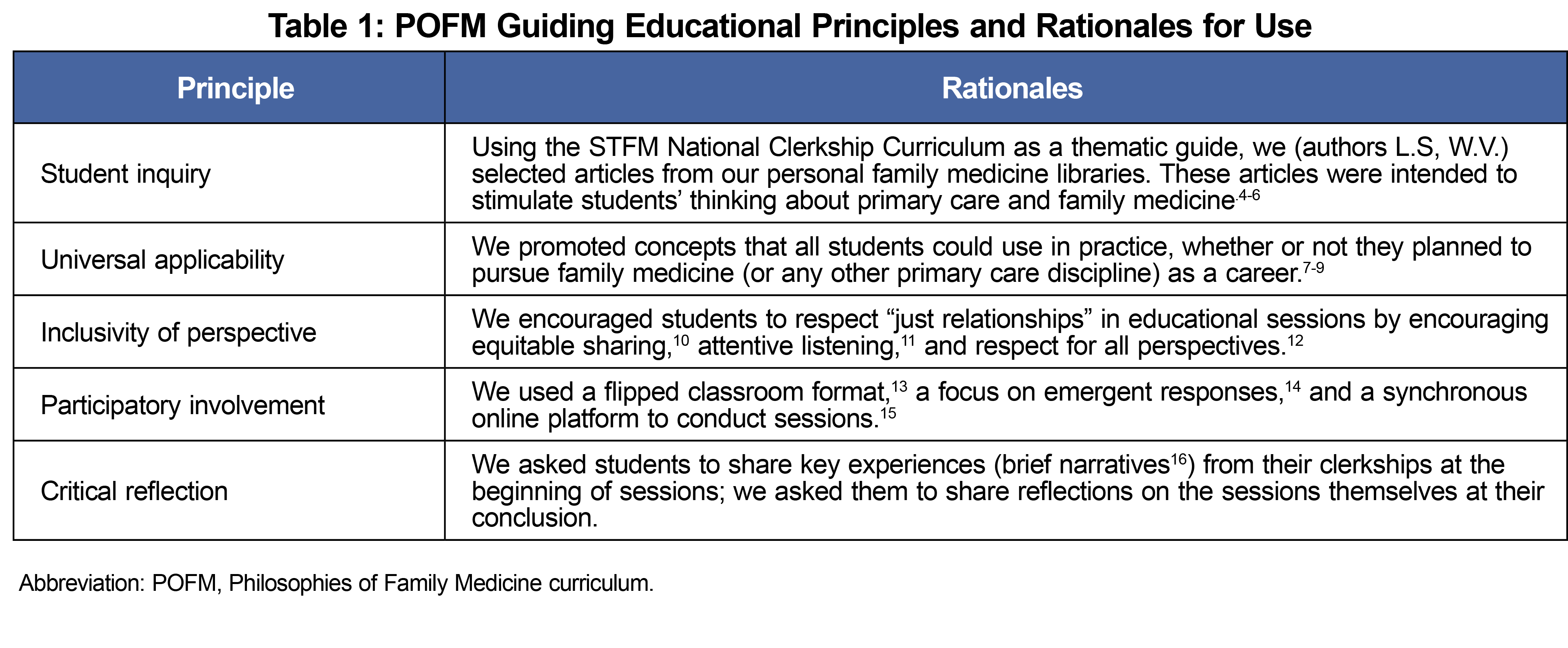

During the first half of the abbreviated 2020-2021 academic year, we used experiential-learning educational principles as a basis for creating POFM (Table 1). In this developmental process, we tested out articles and approaches while simultaneously learning to use the virtual platform effectively.

We piloted POFM and conducted our study during the second half of the academic year to all remaining M3 students. POFM included a brief overview during each clerkship introduction, and five 1-hour, twice-weekly online sessions with 12 small cohorts of M3s distributed across seven clinical sites (total N=64). Each session focused on one theme (Table 2).

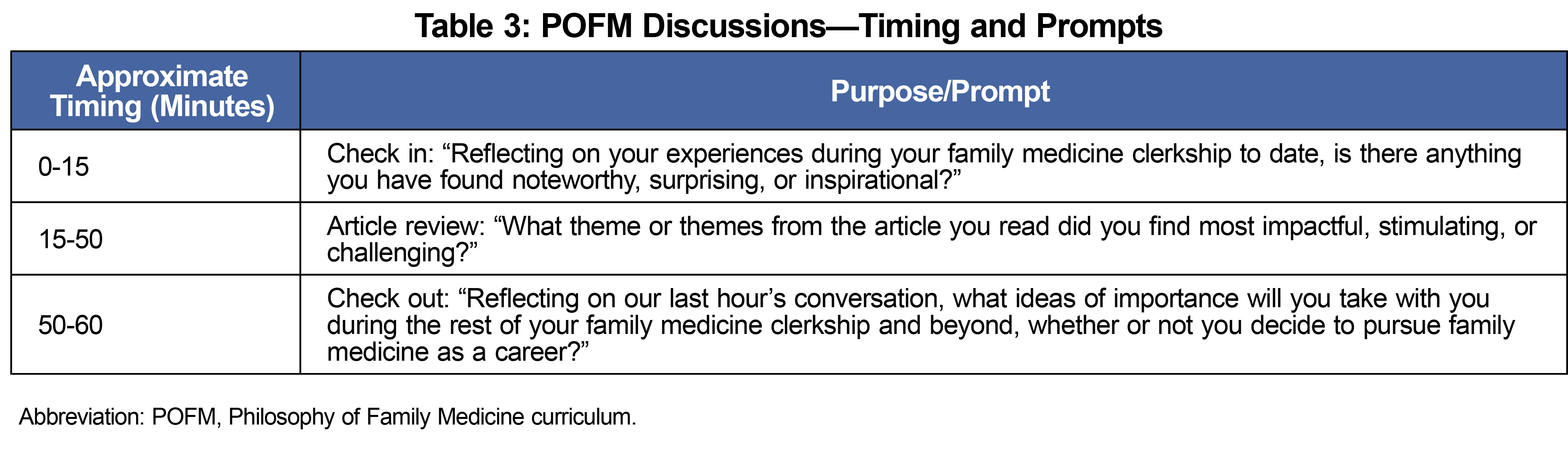

In session 1, a short digital documentary prompted discussion; students read articles (selected based on mutual interests of authors L.S. and W.V., institutional learning objectives, and noted core FM values) prior to other sessions. Although discussion prompts were consistent from cohort to cohort (Table 3), the emerging conversations varied according to students’ comments and our responses—no two sessions unfolded exactly alike.

Evaluation

We used open-ended, qualitative methods and a supplementary quantitative questionnaire to conduct the study. Our institution’s review board deemed the study exempt from review.

Qualitative. Qualitative assessments included (1) key learnings, verbally noted at the end of each session (hand-recorded by L.S. and W.V.); and (2) key themes, documented in writing as open-ended additions to standard anonymous clerkship evaluations.

We listed the key learnings based on frequency of response. The key themes emerged from content analysis of the open-ended responses. Authors A.B., B.S., and W.V. selected three themes based on consensus regarding their frequency and importance.17

Four M4 students, all of whom had participated in POFM as M3s, later reviewed findings in a focus group for member-checking purposes.18,19

Quantitative. At the beginning and end of each rotation, using a quasi-experimental design aimed at assisting with rapid refinement of our approach to teaching POFM,20 we electronically distributed anonymous pre- and postintervention surveys to quantify issues and attitudes about FM that represented educational goals we hoped to achieve. These supplemental surveys were identical and consisted of 15 multiple choice and free-text questions. They are available in the STFM Resource Library.21 We developed these questions by group consensus given our intended outcomes, independent of survey questions used in other studies, and based upon review of the literature and the need to assess quickly an innovative discussion-based curricular intervention targeted to encourage open-ended, values-based student participation.20,22,23 Key questions explored the importance of (1) a FM approach, (2) the biopsychosocial model, (3) person-centered care, and (4) FM’s role in the health care system. Attitudes explored included whether FM (1) has influenced other medical specialties and (2) is an important medical specialty. We also examined students’ interest in pursuing an FM career.

Qualitative Data

Based on frequency of response, the 10 main session-specific learnings, accompanied by brief clarifying explanations, included:

- Listening—active;

- Balance—between hope and reality;

- Empathy—in response to patients’ concerns;

- History—of patients’ lived experiences;

- Politics—relational power in clinical encounters;

- Learning—lifelong;

- Openness—to what emerges in encounters;

- Holistic—broad view of medicine;

- Dance—adaptability in the moment;

- Growth—personal and professional; and,

- Process—health care system integration.

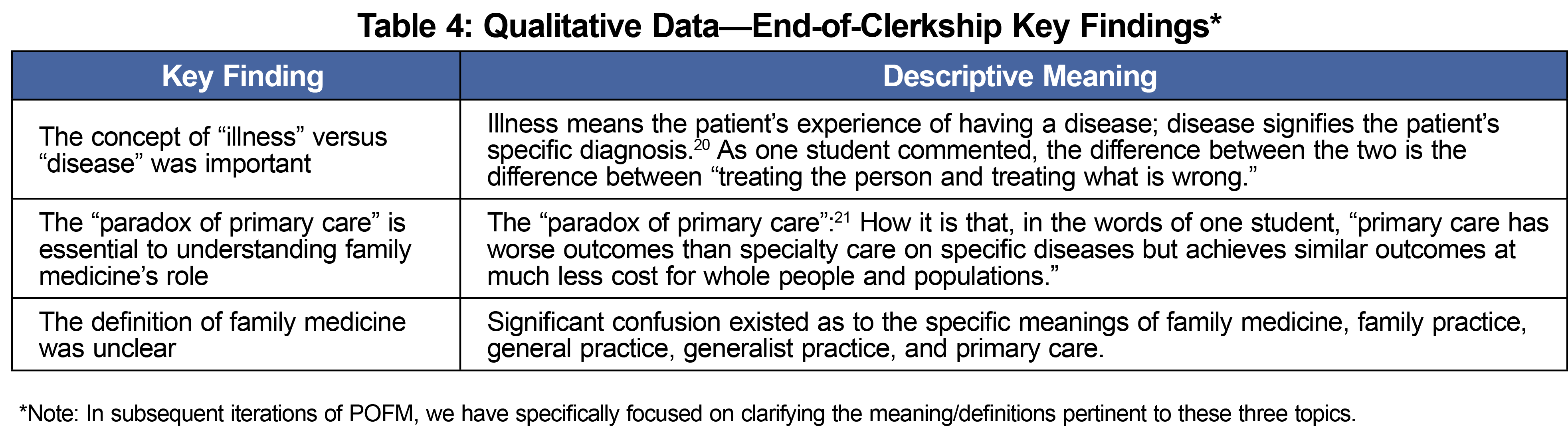

Table 4 summarizes the three main end-of-clerkship themes that students wrote down, with interpretive comments.

Quantitative Data

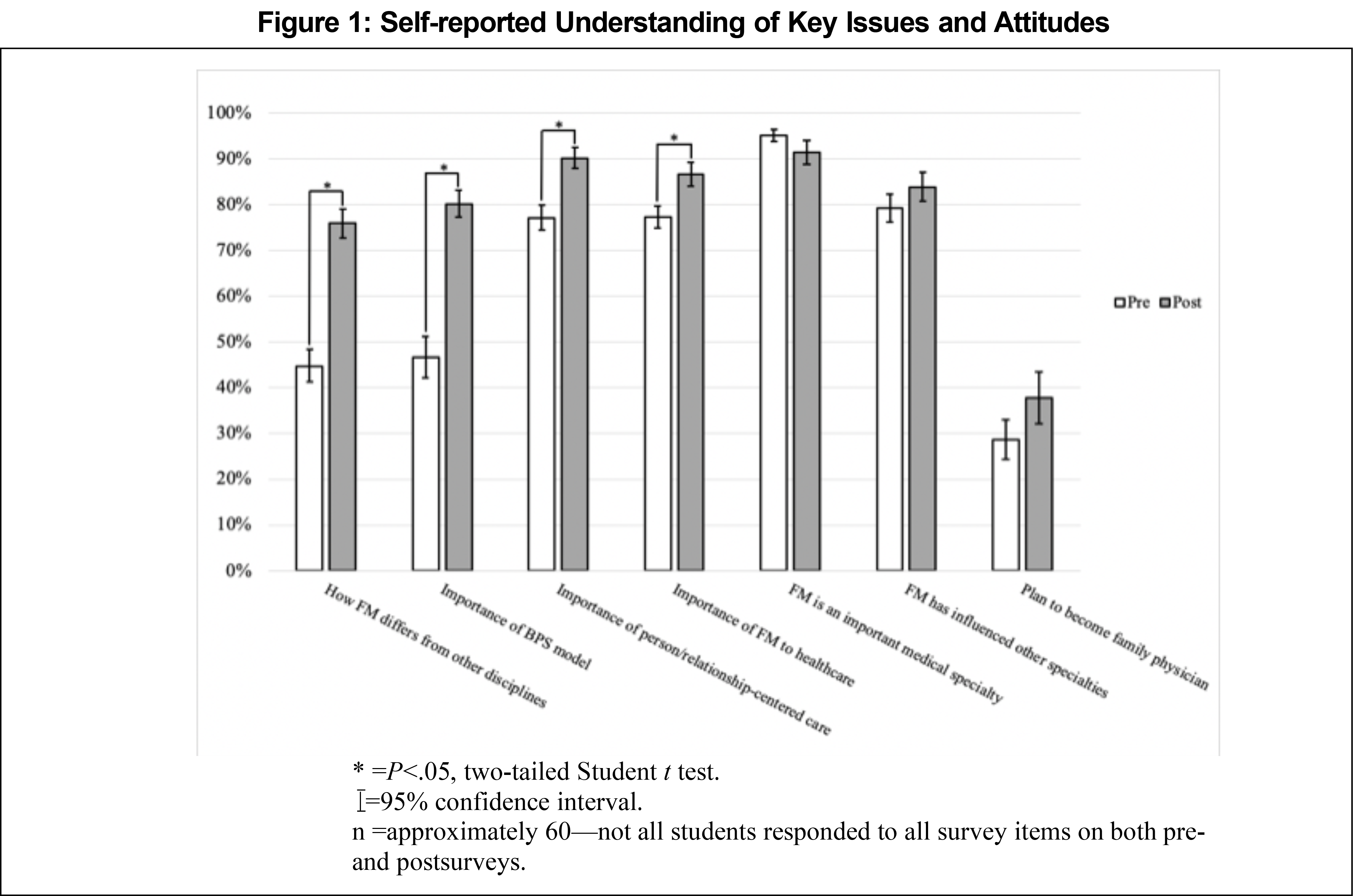

Students responded to pre- and postintervention questions using a rating scale from 1 to 100 (Figure 1). Students’ self-assessed knowledge of and opinions about family medicine increased in almost all areas, including the importance of family medicine to the health care system, knowledge of how family medicine differs from other disciplines, and interest in becoming a family physician.

This mixed-method pilot study demonstrated that a curricular innovation could effectively convey foundational FM philosophies to M3s on their FM clerkships. Qualitatively, it showed that students grasped several concepts key to understanding the role of FM in a functioning health care system. Quantitatively, pre/post self-assessment data supported the themes identified through our qualitative analysis.

Others have attempted to address similar issues by implementing longitudinal integrated clerkships,26 encouraging student participation in extracurricular experiences,27,28 promoting a family systems orientation to clerkships,29 or integrating into curricula topics such as narrative medicine,30 humanities,31 and professionalism.32 POFM extends these efforts.

The main implications of this study include (1) non-patient care educational activities can enhance M3s’ understandings of and attitudes about the importance of FM, (2) innovative curricula can address learning objectives that fall outside the clinical focus of M3s’ education,33 and (3) we can do a better job describing concepts important to our discipline.

Limitations

Our study’s main limitations include (1) this was a single-institution pilot study with a sample that included only one-half of all M3s—including all M3s across the entire academic year might have yielded different results; (2) not all students answered all survey questions, making a robust comparison of pre- and posttest values difficult; (3) an existing, validated assessment tool would have added rigor to our quantitative results; (4) students’ verbal comments were not anonymous, which may have limited honest feedback; and (5) long-term data reflecting students’ clinical behaviors, including specialty choice, are pending. We acknowledge that our quasi-experimental, quantitative pre- and postassessment of attitudes lacks rigor and has limited utility beyond our particular setting and student population.20,34 It was, however, helpful in providing a straightforward association between the curricular intervention and our desired outcomes.

Overall Conclusion

Our pilot study supports that we effectively integrated POFM into our FM clerkship. As POFM matures, as informed by the results of this pilot study, we plan to expand its curricular role, further evaluate its influence on medical student attitudes and behaviors, and increase the academic footing of FM at our institution.

Acknowledgments

We thank the UAMS College of Medicine Class of 2022 for their participation in this curriculum and study.

Presentations: This work was presented as a poster at the 2022 STFM Annual Spring Conference in Indianapolis, Indiana.

References

- The Graduate Education of Physicians. The Report of the Citizen’s Commission of Graduate Medical Education (Millis Commission). American Medical Association; 1966.

- Folsom MB; National Commission on Community Health Services. Health is a Community Affair. Harvard University Press; 1966.

- Meeting the Challenge of Family Practice. The report of the Ad hoc Committee on Education for Family Practice of the Council on Medical Education. American Medical Association; 1966.

- Geyman JP. Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic: the urgent need to expand primary care and family medicine. Fam Med. 2021;53(1):48-53. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.709555

- Hughes LS, Tuggy M, Pugno PA, et al. Transforming training to build the family physician workforce our country needs. Fam Med. 2015;47(8):620-627.

- Phillips RL Jr, Brundgardt S, Lesko SE, et al. The future role of the family physician in the United States: a rigorous exercise in definition. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(3):250-255. doi:10.1370/afm.1651

- Stein HF. Family medicine’s identity: being generalists in a specialist culture? Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(5):455-459. doi:10.1370/afm.556

- Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185-1190. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968

- Niemi PM. Medical students’ professional identity: self-reflection during the preclinical years. Med Educ. 1997;31(6):408-415. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.1997.00697.x

- Koudenburg N, Postmes T, Gordijn EH. Beyond content of conversation: the role of conversational form in the emergence and regulation of social structure. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2017;21(1):50-71. doi:10.1177/1088868315626022

- Boudreau JD, Cassell E, Fuks A. Preparing medical students to become attentive listeners. Med Teach. 2009;31(1):22-29. doi:10.1080/01421590802350776

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

- Moffett J. Twelve tips for “flipping” the classroom. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):331-336. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.943710

- Bleakley A. The curriculum is dead! Long live the curriculum! Designing an undergraduate medicine and surgery curriculum for the future. Med Teach. 2012;34(7):543-547. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.678424

- Patel B, Taggar JS. Virtual teaching of undergraduate primary care small groups during Covid-19. Educ Prim Care. 2021;32(5):296-302. doi:10.1080/14739879.2021.1920475

- Branch W Jr, Pels RJ, Lawrence RS, Arky R. Becoming a doctor. Critical-incident reports from third-year medical students. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(15):1130-1132. doi:10.1056/NEJM199310073291518

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048

- Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212-1222. doi:10.1177/1049732315588501

- Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1802-1811. doi:10.1177/1049732316654870

- Stratton SJ. Quasi-experimental design (pre-test and post-test studies) in prehospital and disaster research. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34(6):573-574. doi:10.1017/S1049023X19005053

- Stone L, Brown A, Jarrett D, Snellgrove B, Ventres W. Philosophies of Family Medicine Survey. STFM Resource Library; 2022.

- Kraut AS, Omron R, Caretta-Weyer H, et al. The flipped classroom: a critical appraisal. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(3):527-536. doi:10.5811/westjem.2019.2.40979

- Miller SZ, Schmidt HJ. The habit of humanism: a framework for making humanistic care a reflexive clinical skill. Acad Med. 1999;74(7):800-803. doi:10.1097/00001888-199907000-00014

- Helman CG. Disease versus illness in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981;31(230):548-552.

- Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):293-299. doi:10.1370/afm.1023

- Latessa R, Beaty N, Royal K, Colvin G, Pathman DE, Heck J. Academic outcomes of a community-based longitudinal integrated clerkships program. Med Teach. 2015;37(9):862-867. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2015.1009020

- Sairenji T, Kost A, Prunuske J, et al. The impact of family medicine interest groups and student-run free clinics on primary care career choice: a narrative synthesis. Fam Med. 2022;54(7):531-535. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.436125

- Geary C, McKee J, Sierpina VS, Kreitzer MJ. The art of healing: an adaptation of the healer’s art course for fourth-year students. Explore (NY). 2009;5(5):306-307. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2009.06.010

- Lang F, Floyd M, Beine KL, Parker M, Abell C. Teaching “family”: evaluating a multidimensional clerkship curriculum. Fam Med. 1996;28(7):484-487.

- Elliot D, Schaff P, Wohrle T, et al. Narrative reflection in the family medicine clerkship-cultural competence in the third-year required clerkships. MedEdPORTAL. 2010:1153. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.1153

- Blasco PG. Literature and movies for medical students. Fam Med. 2001;33(6):426-428.

- Maitra A, Lin S, Rydel TA, Schillinger E. Balancing forces: medical students’ reflections on professionalism challenges and professional identity formation. Fam Med. 2021;53(3):200-206. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.128713

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. National Clerkship Curriculum, 2nded. 2018. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://www.stfm.org/media/1828/ncc_2018edition.pdf

- Yates N, Gough S, Brazil V. Self-assessment: with all its limitations, why are we still measuring and teaching it? Lessons from a scoping review. Med Teach. 2022;44(11):1296-1302. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2022.2093704

There are no comments for this article.