Background and Objectives: According to self-determination theory (SDT), fulfillment of three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—positively impacts people’s health and well-being. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, an accelerated adoption of virtual care practices coincided with a decline in the well-being of physicians. Taking into account the frequency of virtual care use, we examined the relationship between workplace need fulfillment and physician well-being.

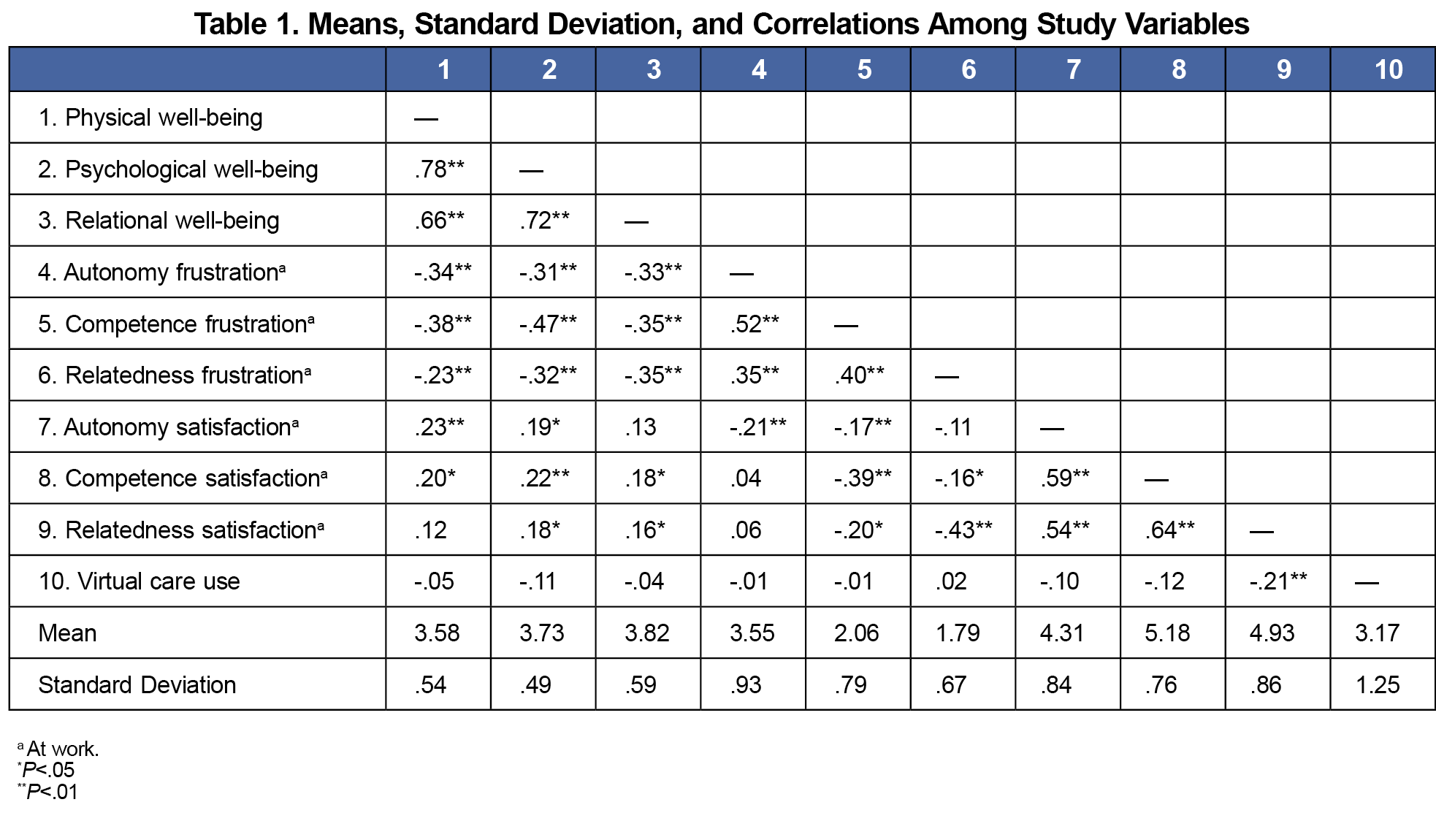

Methods: Using online survey methodology, in March through June 2022, we collected data from 156 family physicians (FPs) in Alberta, Canada. The survey contained scales that measured workplace need satisfaction and frustration, subjective well-being (physical, psychological, and relational), and frequency of virtual care use. We performed correlational and regression analyses of the data.

Results: More frequent use of virtual care was associated with lower relatedness satisfaction among FPs. Controlling for the frequency of virtual care use, frustration of autonomy and competence needs negatively related to FPs’ physical well-being; frustration of competence and relatedness needs negatively related to their psychological and relational well-being.

Conclusions: Findings from this study align with SDT and underscore the importance of supporting FPs’ basic psychological needs, while we work to integrate virtual care into clinical practice. In their day-to-day work, we encourage physicians to reflect on their own sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and consider how using virtual care aligns with these basic needs.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of virtual care (ie, telephone or video appointments) in Canada,1-3 while simultaneously worsening physician well-being.4-6 Yet, in the aftermath of the pandemic, the connection between these two points is unclear.

The virtual care and physician wellness literature is mixed, with some studies showing it can bolster health care providers’ well-being7,8 and others raising concerns regarding stress and burnout.9,10 Though virtual care may not be relied upon as heavily, postpandemic, its value (eg, convenience, safety) is recognized, and its continued use and reimbursement signal that it is likely here to stay.11-13 A better understanding of what physicians need to be well in the digital era is therefore required if we are to implement and scale virtual health care in a humanistic way.

We used self-determination theory (SDT)—a firmly established and empirically supported theory of human motivation and well-being—as a guiding framework for this study.14,15 Central to SDT is the idea that people’s well-being depends on continual support for three basic psychological needs: autonomy (ie, sense of volition), competence (ie, sense of mastery), and relatedness (ie, sense of connectedness).16 A vast body of research supports SDT's principles in workplace settings,17 including work in health care.18-21 SDT has been used to investigate the impact of virtual care on the patient-doctor relationship,22 and the theory’s applications appear to have directly benefited patient outcomes,23-25 including in the telehealth context.26

Of particular relevance to the present investigation was a study that explored physicians’ motivation toward using virtual care and its association with aggregated workplace need fulfillment and overall well-being.27 Taking into account the frequency of virtual care use by FPs, the present study extends that work in two ways: first, we consider each need separately; and second, we examine three distinct aspects of well-being—psychological (eg, having purpose in life, confident beliefs), physical (eg, sleep quality, daily activities), and relational (eg, personal life, relationships). The psychological health of physicians has received increasing amounts of attention,28,29 but the physical and relational domains are also relevant; for example, physicians often work long hours, spend lots of time on computer screens, neglect nutrition and exercise habits, and can suffer from disconnection in their personal lives.30-33 Thus, this study aims to tease apart relationships between the basic psychological needs and physician well-being in the context of virtual care use.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Boards at the University of Calgary and University of Alberta. In March through June 2022, we invited a cross section of family physicians (FPs) in Alberta, Canada, to complete an anonymous online survey. Invitations, containing a consent form with study information and a link to the survey, were sent via listservs, academic newsletters, Alberta Medical Association primary care networks, and the Alberta College of Family Physicians and Well Doc Alberta websites. Participation was voluntary and no incentives were provided.

Participants and Measures

In total, 156 FPs (71% female; 61%<50 years old) responded to the survey. These were largely community-based FPs geographically spread across Alberta. Physicians reported how often they used virtual care in general (telephone or video), ranging from very infrequently (<10% of the time) to very frequently (>80% of the time). We used the BBC Subjective Well-being (BBC-SWB) scale34 to measure physicians’ self-reported physical, psychological, and relational well-being. This scale was chosen because it taps different aspects of well-being, which overall well-being measures are unable to assess. In the general population, the scale showed good psychometric properties,34 and it has been used before to assess physician well-being.35,36 Physicians indicated the degree (1–not at all; 5–extremely) to which each statement on the BBC-SWB scale applied to them, with higher scores indicating greater well-being in each domain.

Physician participants also completed the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale–Work Domain,37 which measures workplace need fulfillment over the past 4 weeks. In the employee population, this scale was shown to be psychometrically sound.37 Physicians rated their level of agreement (1–strongly disagree; 7–strongly agree) with items corresponding to each need (autonomy, competence, relatedness), where higher scores indicate greater satisfaction or frustration with the respective need at work.

The scales were used in their entirety, without modifications. Internal consistency of the measures in this study was good (all subscale α’s >0.70). The measurement instruments are available in the STFM Resource Library.38

Analyses

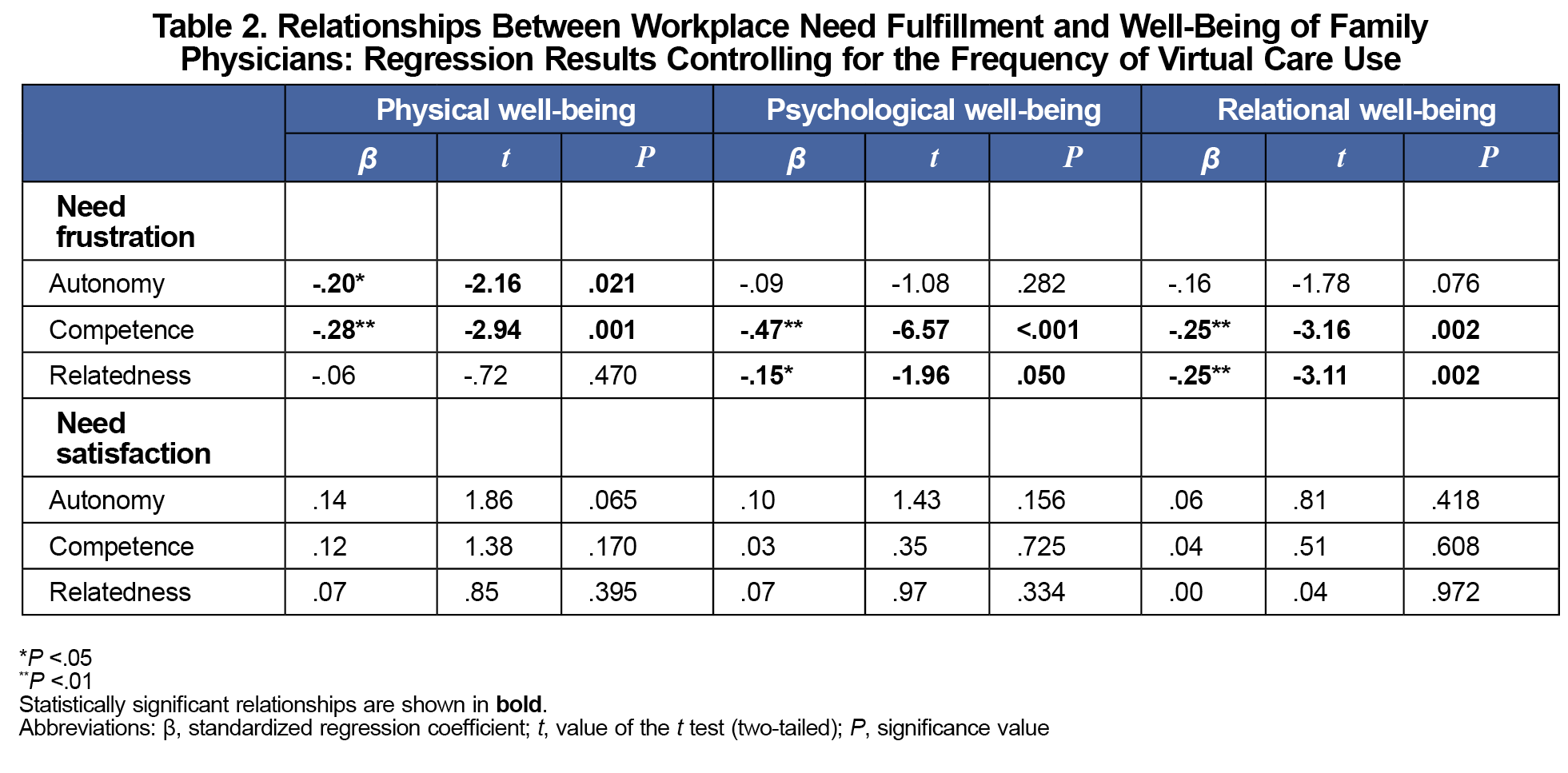

All analyses were performed in SPSS version 26.0 (IBM). We used sample mean imputation to address the issue of missing data, which occurred to a small degree in approximately 30% of surveys. We performed correlational analyses to examine bivariate relationships among the study variables. Next, we performed regression analyses separately for each well-being domain (dependent variable). In each regression, we controlled for the frequency of virtual care use and, employing the stepwise approach, tested the contributions of autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction and frustration (independent variables) to each well-being domain.

The majority (85%) of physicians reported using virtual care less than 50% of the time, and more frequent use of virtual care was associated with lower relatedness satisfaction at work (r=–0.21; P<.01; Table 1). Regression analysis (Table 2) showed that workplace need frustration, but not need satisfaction, significantly related to physicians’ subjective well-being. Specifically, autonomy and competence frustration negatively related to physical well-being, while competence and relatedness frustration negatively related to psychological and relational well-being.

The present study focused on virtual care use in relation to FPs’ basic psychological needs at work. It adds to the literature in several ways. First, considering each psychological need and assessing its relationships with three domains of well-being allowed us to build on prior work27 and examine physician well-being at a more granular level. Second, we observed that FPs who reported experiencing greater need frustration at work experienced poorer well-being in all three domains—physical, psychological, and relational. This underscores the importance of supporting family physicians in meeting their autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs in the workplace. Finally, we observed that virtual care use negatively related to physicians’ relatedness satisfaction at work, highlighting the challenge of maintaining a sense of meaningful connection with others in virtual environments. Future research should seek to identify factors that exacerbate or mitigate this finding; for example, finding a balance between in-person and virtual visits, or setting personally meaningful goals39 (eg, maximizing relationships and service when using virtual care), which could help support FPs’ sense of relatedness at work.

In terms of limitations, our survey combined telephone and video visits into one category, when in reality they may have different impacts. Further, we did not account for other things that could impact physician well-being, such as actual hours worked or time spent on nonclinical tasks. Exploring these specific factors and provider well-being, including in other specialties, health professions, and geographic regions, is therefore warranted. As physicians continue to adapt to caring for patients in increasingly digital settings, let us not forget physicians’ basic psychological needs. Barriers to meeting these needs represent ultimate obstacles to physician well-being and therefore quality of patient care.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by funding from the Department of Family Medicine Research Program at the University of Alberta.

Presentations: This study was presented in part at the Family Medicine Research Day on July 9, 2023, at the University of Alberta.

References

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Virtual care: a major shift for Canadians receiving physician services. CIHI; March 24, 2022. https://www.cihi.ca/en/virtual-care-a-major-shift-for-canadians-receiving-physician-services

- Bhatia RS, Chu C, Pang A, Tadrous M, Stamenova V, Cram P. Virtual care use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a repeated cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2021;9(1):E107-E114. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200311

- Singer A, Kosowan L, LaBine L, et al. Characterizing the use of virtual care in primary care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):320. doi:10.1186/s12875-022-01890-w

- Myran DT, Roberts R, McArthur E, et al. Mental health and addiction health service use by physicians compared to non-physicians before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med. 2023;20(4):e1004187. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1004187

- Adams GC, Le T, Alaverdashvili M, Adams S. Physicians’ mental health and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: one year exploration. Heliyon. 2023;9(5):e15762. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15762

- Canadian Medical Association. COVID-19: impacts on physician health and wellness in Canada: report executive summary. CMA; 2021 Accessed February 19, 2024. https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/hub/COVID-19-Impacts-PHW-Summary-EN.pdf

- Malouff TD, TerKonda SP, Knight D, et al. Physician satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Mayo Clinic Florida experience. MCP.Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(4):771-782. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.06.006

- deMayo R, Huang Y, Lin ED, et al. Associations of telehealth care delivery with pediatric health care provider well-being. Appl Clin Inform. 2022;13(1):230-241. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1742627

- Gomez T, Anaya YB, Shih KJ, Tarn DM. A qualitative study of primary care physicians’ experiences with telemedicine during COVID-19. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(suppl):S61-S70. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200517

- Mano MS, Morgan G. Telehealth, social media, patient empowerment, and physician burnout: seeking middle ground. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2022;42:1-10. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100030

- Canadian Medical Association. Virtual Care in Canada: Progress and Potential. CMA; February 2022. Accessed February 19, 2024. https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/2022-02/Virtual-Care-in-Canada-Progress-and-Potential-EN.pdf

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. The Expansion of Virtual Care in Canada: New Data and Information. CIHI; 2023. Accessed February 19, 2024. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/expansion-of-virtual-care-in-canada-report-en.pdf

- Welk B, McArthur E, Zorzi AP. Association of virtual care expansion with environmental sustainability and reduced patient costs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2237545. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.37545

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-Determination and Intrinsic Motivation in Human Behavior.Plenum; 1985. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68-78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryan RM. Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. J Pers. 1995;63(3):397-427. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x

- Ryan RM, Duineveld JJ, Di Domenico SI, Ryan WS, Steward BA, Bradshaw EL. We know this much is (meta-analytically) true: a meta-review of meta-analytic findings evaluating self-determination theory. Psychol Bull. 2022;148(11-12):813-842. doi:10.1037/bul0000385

- Lynch MF, Plant RW, Ryan RM. Psychological needs and threat to safety. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2005;36(4):415-425. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.36.4.415

- Babenko O. Professional well-being of practicing physicians: the roles of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.3390/healthcare6010012

- Burstyn I, Holt K. Pride and adversity among nurses and physicians during the pandemic in two US healthcare systems: a mixed methods analysis. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):304. doi:10.1186/s12912-022-01075-x

- Hood C, Patton R. Exploring the role of psychological need fulfilment on stress, job satisfaction and turnover intention in support staff working in inpatient mental health hospitals in the NHS: a self-determination theory perspective. J Ment Health. 2022;31(5):692-698. doi:10.1080/09638237.2021.1979487

- Neufeld A, Bhella V, Svrcek C. Pivoting to be patient-centred: a study on hidden psychological costs of tele-healthcare and the patient-provider relationship. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2022;20(1). doi:10.46743/1540-580X/2022.2112

- Williams GC, Grow VM, Freedman ZR, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(1):115-126. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.115

- Williams GC, Patrick H, Niemiec CP, et al. Reducing the health risks of diabetes: how self-determination theory may help improve medication adherence and quality of life. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(3):484-492. doi:10.1177/0145721709333856

- Murray A, Hall AM, Williams GC, et al. Effect of a self-determination theory-based communication skills training program on physiotherapists’ psychological support for their patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(5):809-816. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.007

- Chemtob K, Rocchi M, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Kairy D, Fillion B, Sweet SN. Using tele-health to enhance motivation, leisure time physical activity, and quality of life in adults with spinal cord injury: a self-determination theory-based pilot randomized control trial. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;43:243-252. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.03.008

- Neufeld A, Babenko O, Bhella V. Family physician motivation and well-being in the digital era. Ann Fam Med. 2023;21(6):496-501. doi:10.1370/afm.3031

- Shanafelt TD. Physician well-being 2.0: where are we and where are we going? Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(10):2,682-2,693.doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.06.005

- Sinskey JL, Margolis RD, Vinson AE. The wicked problem of physician well-being. Anesthesiol Clin. 2022;40(2):213-223. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2022.01.001

- Soler-Gonzalez J, San-Martín M, Delgado-Bolton R, Vivanco L. Human connections and their roles in the occupational well-being of healthcare professionals: a study on loneliness and empathy. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1475. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01475

- Myers MF. The well-being of physician relationships. West J Med. 2001;174(1):30-33. doi:10.1136/ewjm.174.1.30

- Canadian Medical Protective Association. Physician health: putting yourself first. CMPA; April 2022. Accessed February 19, 2024. https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/advice-publications/browse-articles/2015/physician-health-putting-yourself-first

- Wiskar K. Physician health: a review of lifestyle behaviours and preventative health care among physicians. BCMJ. 2012;54(8):419-423.

- Pontin E, Schwannauer M, Tai S, Kinderman P. A UK validation of a general measure of subjective well-being: the modified BBC subjective well-being scale (BBC-SWB). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):150. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-150

- Finuf KD, Lopez S, Carney MT. Coping through COVID-19: A mixed method approach to understand how palliative care teams managed the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;39(7):874-880. doi:10.1177/10499091211045612

- Bhat SG, Nagaraj M, Balentine C, et al. Assessing a structured mental fitness program for academic acute care surgeons: a pilot study. J Surg Res. 2024;295:9-18. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2023.09.052

- Schultz PP, Ryan RM, Niemiec CP, Legate N, Williams GC. Mindfulness, work climate, and psychological need satisfaction in employee well-being. Mindfulness (NY). 2015;6(5):971-985. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0338-7

- LaPlante G, Babenko O, Neufeld A. Measurement instruments. STFM Resource Library; 2024. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/measurement-instruments-1?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

- Sheldon KM, Arndt J, Houser-Marko L. In search of the organismic valuing process: the human tendency to move towards beneficial goal choices. J Pers. 2003;71(5):835-869. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.7105006

There are no comments for this article.