Promoting scholarly work within professional organizations can lead to professional growth, deepen the quality of ongoing work, increase collaboration, and enhance one’s academic reputation.1,2 Faculty can share their scholarship and meet this expectation by presenting at national conferences. However, the peer-review process is increasingly competitive as national conferences often receive high volumes of submissions. This manuscript outlines evidence-based guidance and best practices for developing effective conference submissions and is intended to be of particular benefit to junior faculty in academic family medicine. These guidelines are based on existing literature and the collective professional experience of the authors, who are a workgroup within the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Faculty Development Collaborative.*

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE

Pursuing Scholarship: Creating Effective Conference Submissions

Nathan Culmer, PhD | Joanna Drowos, DO, MBA | Monica DeMasi, MD | Tina Kenyon, MSW, ACSW | Edgar Figueroa, MD, MPH | Andrea Pfeifle, EdD, PT, FNAP | John Malaty, MD | F. David Schneider, MD, MSPH | Jennifer Hartmark-Hill, MD

PRiMER. 2024;8:13.

Published: 2/19/2024 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2024.345782

Medical educators are expected to disseminate peer-reviewed scholarly work for academic promotion and tenure. However, developing submissions for presentations at national meetings can be confusing and sometimes overwhelming. Awareness and use of some best practices can demystify the process and maximize opportunities for acceptance for a variety of potential submission categories. This article outlines logistical steps and best practices for each stage of the conference submission process that faculty should consider when preparing submissions. These include topic choice, team composition, consideration of different submission types, and strategies for effectively engaging participants.

Initial Preparations

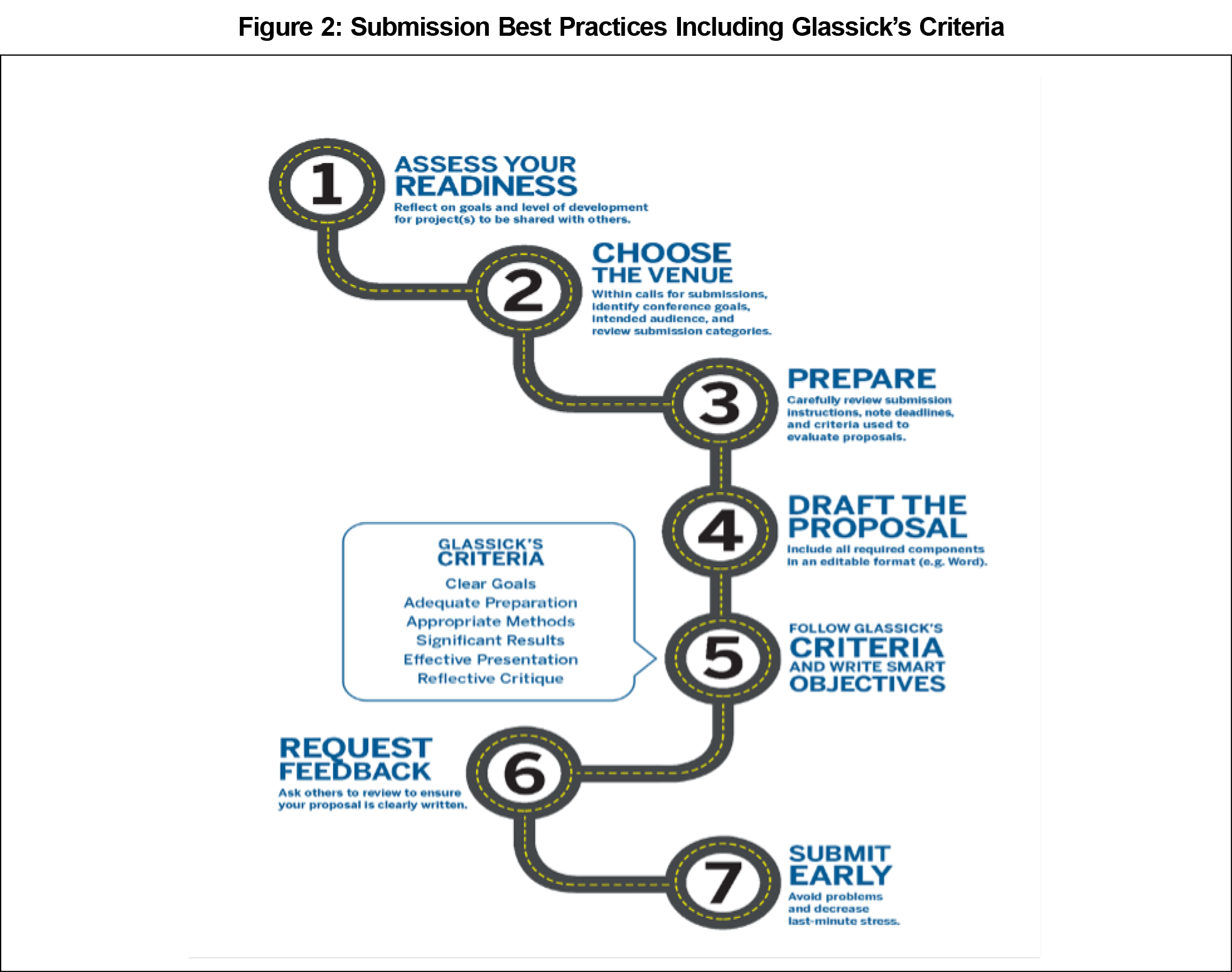

Glassick’s criteria (Figure 2) provide a useful framework for synthesizing and communicating scholarly work, with adequate preparation being essential.3,4 Furthermore, submissions with clear goals that have practical value, resonate with conference themes, and/or add something new to the discussion are more likely to be accepted and appeal to the audience.

In our experience, conference committees prioritize collaborative submissions. Because of this, we recommend building diverse submission teams. These can involve multi-institutional, interdisciplinary, interprofessional, or include learner and/or patient coauthors. Not only does this enable collaboration, but it also adds new perspectives to the work, creates opportunities for networking, and stimulates professional growth.5

A call for proposals is an opportunity to reflect on the readiness of your work, whether it fits well with the conference theme and subtopics, and if attendance meets your professional goals.6 Identification of your project’s stage of development and the goals for presenting help in selection of the ideal conference submission category. For example, if you are just getting started with an innovative or promising project, but it is not yet fully developed or has not yet produced adequate data to present as a completed project, it may still meet the criteria for a “developing project” or “Works-in-Progress" submission. This is an opportunity to share work at an earlier stage and receive feedback to inform next steps. More developed or completed projects with analyzed data and conclusions are more suitable for other categories such as presentations, workshops, or seminars, depending on the criteria of each conference’s call for proposals.

Submission Preparation and Logistics

Collaborate with colleagues to review submission criteria, determine alignment of ideas with conference themes and requirements, and create a first draft, noting stated deadlines, requirements, detailed instructions, appropriate topics, and evaluation criteria. Gather author-specific information required by the submission form early to avoid last-minute difficulties or errors. During this phase, it is important to build group consensus around the order of authorship and assign roles/responsibilities based on the timeline, level of contribution, and expertise. The first author typically accepts primary responsibility for the submission and seeing it through to completion. Commonly, the last author is a senior faculty member or content expert who completes the final review. In interprofessional collaborations where team member contributions are equal, authorship order between the first and last-named person is generally arranged in alphabetical order.7

It is essential to carefully follow all instructions and formatting requirements for the submission category. These requirements are used to form the rubrics that reviewers are given to evaluate submissions. What’s more, presentation title, content currency, and readability of the abstract strongly influence reviewer impressions. Presentation titles should be descriptive and concise. Abstracts should be focused and succinct, include all categories and information, and follow the order indicated in the instructions.8 Appearance and arrangement matter for both the submission and the presentation. If a presentation involves research, the results section should be prioritized in word count calculations to help reviewers understand the significance of the work.9

Research Presentations. Research presentations invite valuable feedback on various aspects of an ongoing project or particular challenges. Research presentations should follow the same organization as a research paper, including sections covering the introduction, methods, results, and discussion/future directions (IMRAD).10 While projects may have multiple research questions or hypotheses, a focus on one main area is recommended for clearer presentation proposals. An option for projects with multiple research questions/hypotheses is to submit an individual abstract for each.

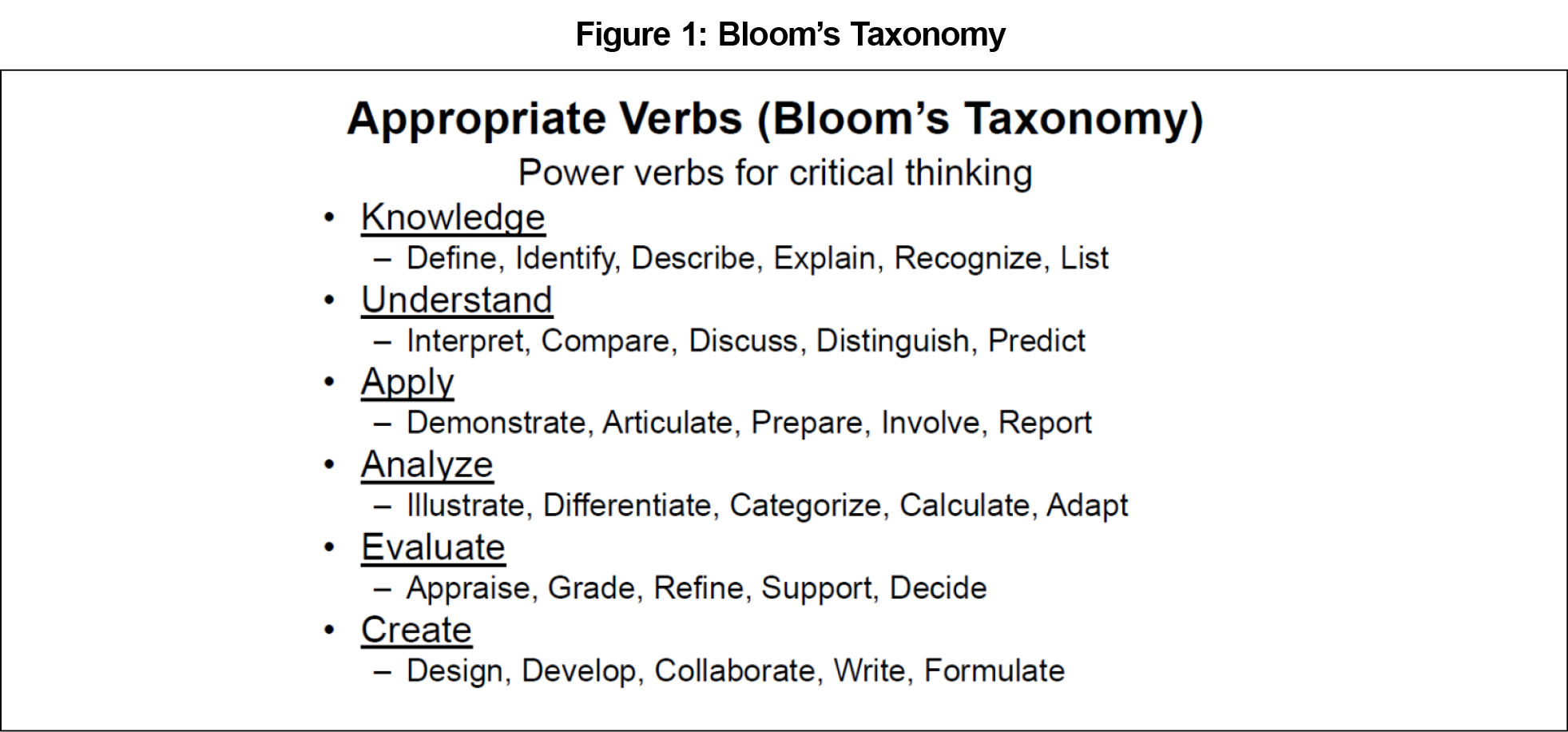

Educational Presentations. Educational presentations are not necessarily organized the same as research projects, although some calls for proposals do not differentiate between the two. If the call for proposals does not specify a format, the IMRAD format is appropriate to follow.10 It is important to adhere to the instructions and to use the prescribed format to stay organized and focused, while clearly emphasizing the most important points and takeaways. Glassick suggests identification of a few clear and concise learning targets to guide presentation objectives. The SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-lined) format may be used for developing broad goals.11 Subsequently, verbs from Bloom’s taxonomy (Figure 1) are helpful to translate goals into measurable learning objectives.12 It is preferable to organize learning objectives in a natural progression from the more basic (knowing or understanding) to those of a higher level of involvement (analyzing, evaluating, and creating).13 The proposal should be drafted with all required components in an editable format, to allow for collaborative editing. Proposals should use clear language, avoid jargon, and stay within the specified word limit.14

Engaging Participants

Submission requirements frequently ask how the presenters will engage participants and include this criterion in the review and scoring process. Examples of meaningful ways to interactively involve session attendees include small group discussions/activities (“think-pair-share") and audience participation platforms (such as Poll Everywhere®, Padlet®, or Slido®). The engagement plan should be carefully integrated into the presentation to enhance participants’ learning without disrupting the flow or overshadowing key messages. Slides and other presentation aids should be kept simple and aesthetically appealing to make or clarify the main points, without being used as a script.15 Low-tech approaches can be as effective as more technologically involved methods. For example, a simple method such as a show of hands in response to a question can enlist engagement and provide information without taking much time or risking technological glitches. Whatever the method, promoting dialogue and interchange between presenters and participants is stimulating and improves the learning experience.

Last Steps and Best Practices

Beginning proposal preparation well before the deadline is wise to avoid last-minute technology glitches that could impede the online submission process. Ensure the title is descriptive, succinct, and concrete, not whimsical or obscure.14 Checklist items may include obtaining feedback from peers (regarding clarity and completeness), confirming plans for participant engagement, and ensuring the submission’s stated purpose and key points are clear and aligned with conference themes. Consulting experienced mentors with a track record of successful submissions can also enhance success.

Acceptance is never guaranteed. Conferences receive greater numbers of high-quality submissions than available slots. Trends influence acceptance decisions, and reviewers sometimes have less experience than authors in a specific content area. This is where Glassick’s Reflective Critique is important. There are a variety of reasons for rejection. Some reasons are within the author’s control such as submission quality issues or lack of alignment between the submission topic and the conference theme. Other reasons include too many similar submissions in a category. However, rejection offers opportunities. It is helpful to request feedback from reviewers to improve future submissions. Updated work may represent a good fit for other conferences. Additionally, there are resources with advice for handling rejection constructively, resulting in improvements.16,17

Best practices for submission that maximize the chances of having a conference proposal accepted can be summarized in the following steps which reinforce best practices to follow (Figure 2).

Disseminating scholarly work through conference submissions can seem daunting to new medical educators, particularly with increased competition (in terms of submission numbers) or added pressure from tenure or promotion requirements from home institutions. However, the process of developing and submitting a conference abstract for presentation at national meetings can be fulfilling and meaningful to professional and career development. Following best practice tips can maximize opportunities for success and growth as well as minimize stress. Using the steps outlined here, faculty can plan, prepare, and submit a high-quality abstract with increased chances of acceptance for presentation.

* Footnote: This particular workgroup is composed of leaders in academic family medicine with an average of 18.7 years of experience in medical education, have presented an average of 86.9 presentations at professional conferences, as well as serving on conference program committees and as conference submission reviewers.

References

- Boyer EL. Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities for the Professoriate.The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1990.

- Beasley BW, Simon SD, Wright SM; The Prospective Study of Promotion in Academia (Prospective Study of Promotion in Academia). A time to be promoted. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(2):123-129. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00297.x

- Glassick CE, Huber MR, Maeroff GI. Scholarship Assessed: Evaluation of the Professoriate.Jossey-Bass; 1997.

- Shapiro ED, Coleman DL. The scholarship of application. Acad Med. 2000;75(9):895-898. doi:10.1097/00001888-200009000-00010

- Trejo J. A reflection on faculty diversity in the 21st century. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28(22):2911-2914. doi:10.1091/mbc.e17-08-0505

- Drowos J, Berry A, Wyatt TR, Gupta S, Minor S, Chen W. Strategic Conferencing: opportunities for Success. Acad Med. 2021;96(11):1622. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004221

- Mongeon P, Smith E, Joyal B, Larivière V. The rise of the middle author: investigating collaboration and division of labor in biomedical research using partial alphabetical authorship. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184601. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184601

- Boullata JI, Mancuso CEA. A “how-to” guide in preparing abstracts and poster presentations. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22(6):641-646. doi:10.1177/0115426507022006641

- Ameen S, Praharaj SK, Menon V. “Two Minutes More!” Preparing Slides for Conference Research Presentations. Indian J Psychol Med. 2023;45(1):1-4. doi:10.1177/02537176221142555

- Pierson DJ. How to write an abstract that will be accepted for presentation at a national meeting. Respir Care. 2004;49(10):1206-1212.

- Doran G. There’s a SMART Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives. Journal of Management Review. 1981;70:35-36.

- Bloom B, Engelhart M, Furst E, Hill W, Krathwohl D. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Vol. Handbook I: Cognitive domain.David McKay Company; 1956.

- Chatterjee D, Corral J. How to Write Well-Defined Learning Objectives. J Educ Perioper Med. 2017;19(4):E610. Published 2017 Oct 1.

- Simons J. How to prepare conference abstracts and poster presentations. Nurs Child Young People. 2016;28(7):18. doi:10.7748/ncyp.28.7.18.s19

- Older J. Preparing the conference paper. Can J Psychiatry. 1984;29(3):252-253. doi:10.1177/070674378402900312

- Jaremka LM, Ackerman JM, Gawronski B, et al. Common Academic Experiences No One Talks About: Repeated Rejection, Impostor Syndrome, and Burnout. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2020;15(3):519-543. doi:10.1177/1745691619898848

- Cook DA. Twelve tips for getting your manuscript published. Med Teach. 2016;38(1):41-50. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2015.1074989

Lead Author

Nathan Culmer, PhD

Affiliations: University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL

Co-Authors

Joanna Drowos, DO, MBA - Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL

Monica DeMasi, MD - Providence Portland Oregon Family Medicine Residency Program, Portland, OR

Tina Kenyon, MSW, ACSW - Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency/Geisel School of Medicine at NH Dartmouth, Concord, NH

Edgar Figueroa, MD, MPH - Student Health Services, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY

Andrea Pfeifle, EdD, PT, FNAP - Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

John Malaty, MD - University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

F. David Schneider, MD, MSPH - University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Jennifer Hartmark-Hill, MD - University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ

Corresponding Author

Joanna Drowos, DO, MBA

Correspondence: 777 Glades Road, Building 71, Suite 215A, Boca Raton, FL 33431

Email: jdrowos@health.fau.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.