Background and Objectives: Mentorship is critical for the career development of health care professionals and educators. Facilitating successful mentorship is valuable in supporting future leaders and educators in family medicine. Since 1988, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s New Faculty Scholars (NFS) program has provided 1-year mentorship opportunities for new faculty. This qualitative study used group concept mapping to identify the characteristics of successful mentorship relationships within the NFS program.

Methods: Eight New Faculty Scholars (five mentors, three mentees) from 2015 to 2021 participated in a virtual 90-minute group concept-mapping and pattern-matching session. Participants generated statements in response to a prompt about successful features of mentorship relationships. Participants categorized responses by similarity and rated each statement on a numerical scale from 1 to 5 (1 indicating lowest, 5 indicating highest) according to importance, current presence within the program, and feasibility.

Results: Statements generated by participants were grouped into seven common themes. Categories rated most important included interpersonal skills, mentor soft skills, and mentor preparation. Structured processes and goal setting, mentor soft skills, and mentor preparation were rated most feasible in terms of future improvement.

Conclusions: Interpersonal skills, mentor soft skills, and mentor preparation were the most highly rated by participants, but also displayed the largest disparity when compared to ratings on current presence. Future efforts to improve interpersonal communication and mentor training can potentially lead to greater satisfaction with the NFS program. The most highly rated categories indicated the primary benefit of the relational components of mentorship.

Mentorship in medicine plays a highly significant role in not only imparting skills and knowledge, but also often shaping a mentee’s specialty choice, professional behavior, and career aspirations. Mentorship is often mutually beneficial, providing professional satisfaction and work-life balance for mentors and mentees.1 Mentorship is also associated with higher levels of involvement in academic medicine and leadership.2,3 Assessments of mentorship have found that components most highly rated in importance include institutional support, time availability, and shared career interests.4

The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) is a community for research collaboration, advocacy, and leadership.5 Since 1988, STFM’s New Faculty Scholars (NFS) program has provided 1-year mentorship for new family medicine faculty.6 Participants are STFM members who have been faculty in a family medicine department, residency program, or academic family medicine institution for 2 to 4 years. Mentees are partnered with a senior faculty member for 1 year for advising, career guidance, and networking. These mentorships are formed based on a survey-based assessment of the mentee’s professional goals, background, work setting, and occasionally demographic characteristics if a preference is expressed by the mentee. To ensure continued development of family medicine educators and leaders, identifying how the NFS program has contributed to mentee and mentor development and how it may be further improved is vital. This mixed-methods study used group concept mapping (GCM) and pattern matching to identify and prioritize common themes characterizing the features of successful mentoring relationships in the NFS program.

Study participants were recruited from mentors and mentees in the NFS program who participated during the years 2015 to 2021. Note that the program’s 2020 cohort was delayed until 2021 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic but overall did not affect the program’s functions or contribute to any significant limitations. NFS mentees are active STFM members who have been full-time faculty in family medicine for 2 to 4 years. NFS mentors are active STFM Foundation Trustees, longtime members, or former NFS mentees. As noted by Jackson and Trochim, the minimum number of sorters in a GCM session is 10.7 To meet this minimum, 160 eligible participants consisting of 90 mentees and 70 mentors were invited via e-mail to the virtual GCM session.

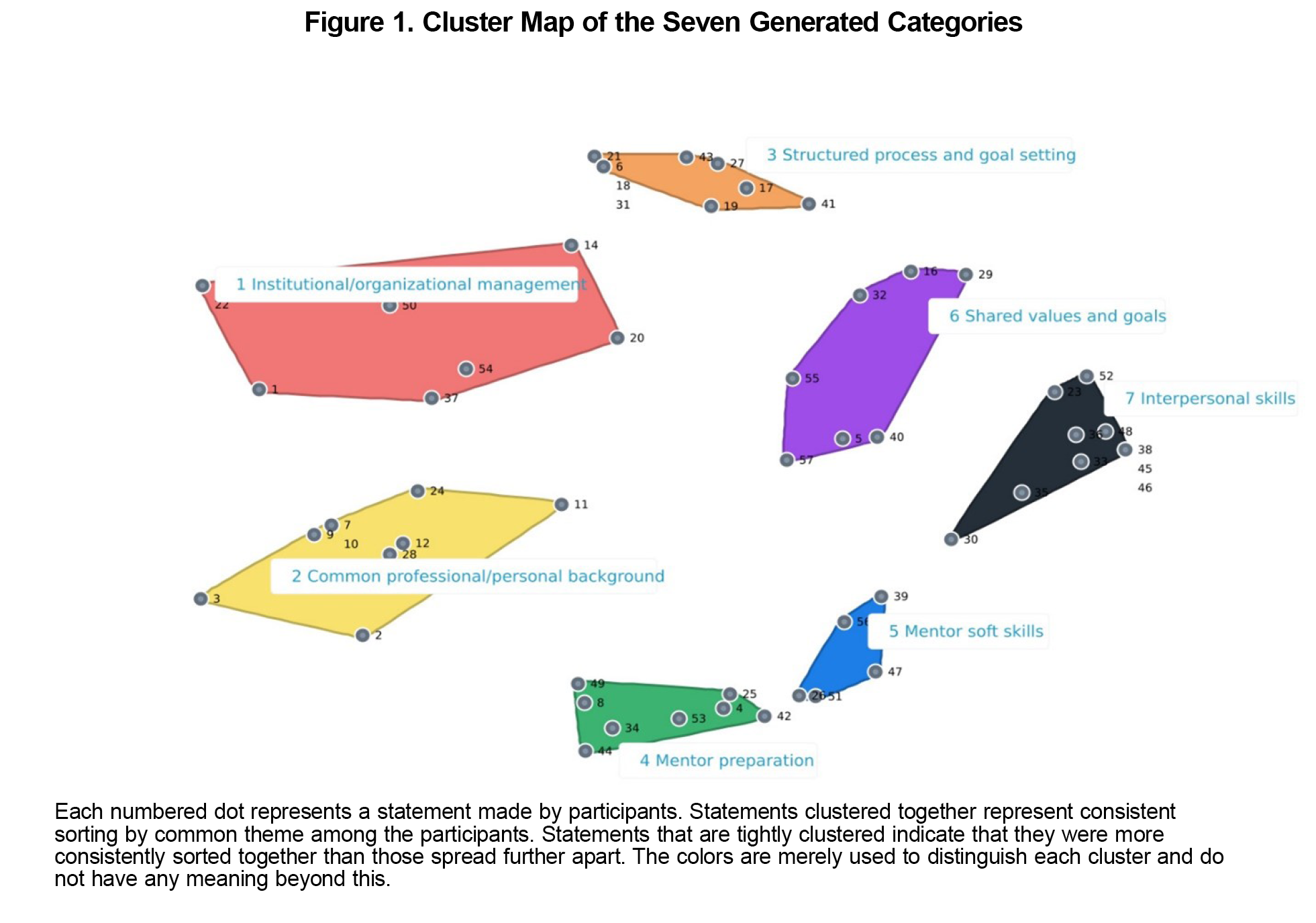

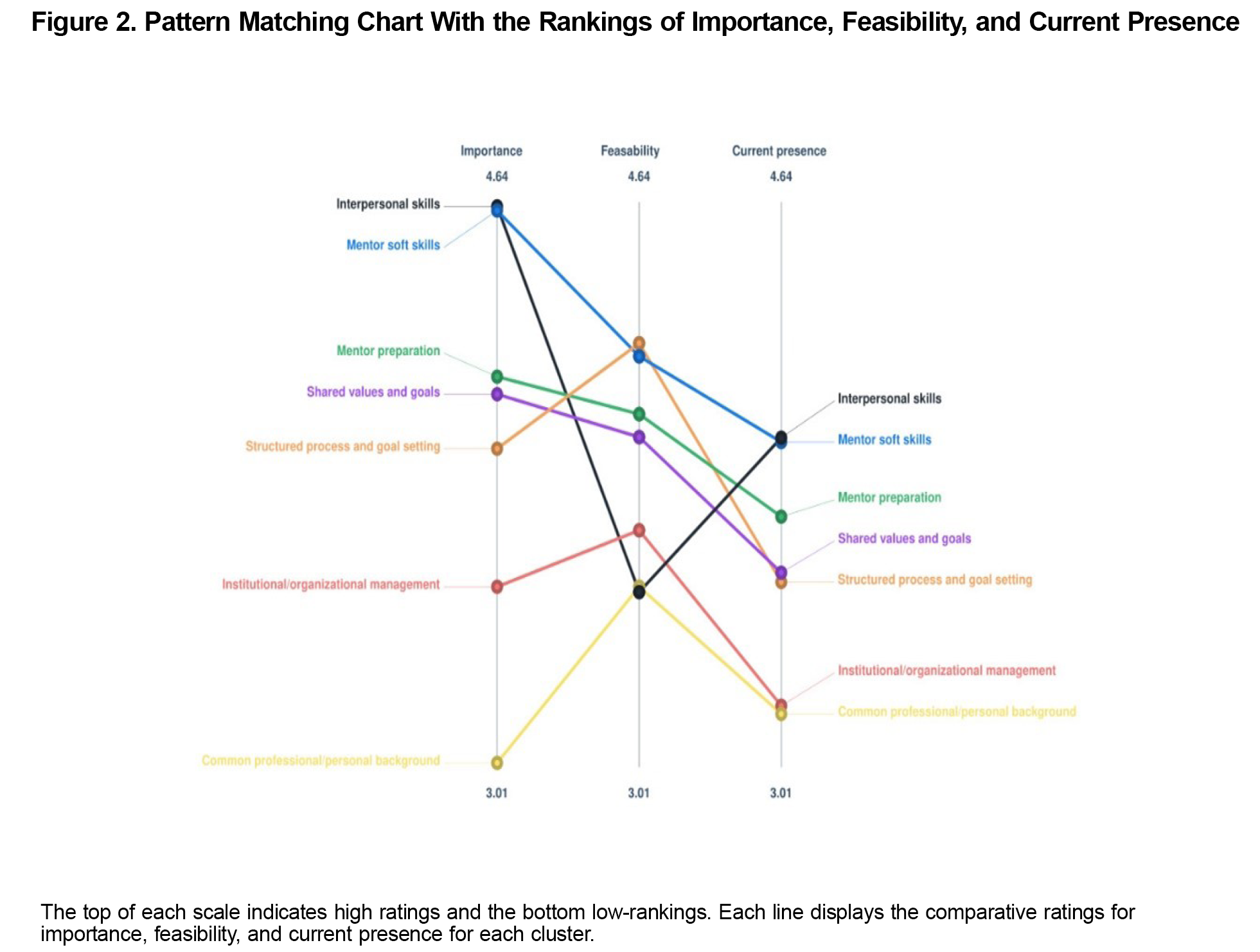

GCM is participatory mixed-method research that uses a structured group process, including brainstorming, sorting, and ranking, to visually organize and represent the collective thoughts and ideas of a group in response to a prompt. Integral to the GCM process is the input of stakeholders most affected by the research subject to assess their priorities, perceptions, and values.8 This combined qualitative and statistical analysis displays a wide range of uses for organizational assessment, development, and planning.9 Notably, GCM has been found in systematic reviews to display strong internal validity and consistency.10 In the brainstorming step, participants attended a facilitated group brainstorming session in which they generated statements in response to the prompt: “What are the features that make mentorship successful?” Researchers removed duplicate and erroneous entries. During sorting, participants independently sorted statements into groups by common themes. Participants rated the statements on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest) according to importance, current presence, and feasibility. Results were aggregated by groupwisdom (Concept Systems Inc) software into a point map and cluster map, in which participants’ sorted statements were aggregated and displayed (Figure 1). These clusters were analyzed and labeled by researchers according to common themes among participant statements. groupwisdom was used to generate an average ranking along the metrics of importance, current presence, and feasibility, which were compared and displayed in a pattern-matching chart. This chart (Figure 2) illustrates the participant’s prioritization of each theme and comparisons among importance, current presence, and feasibility.

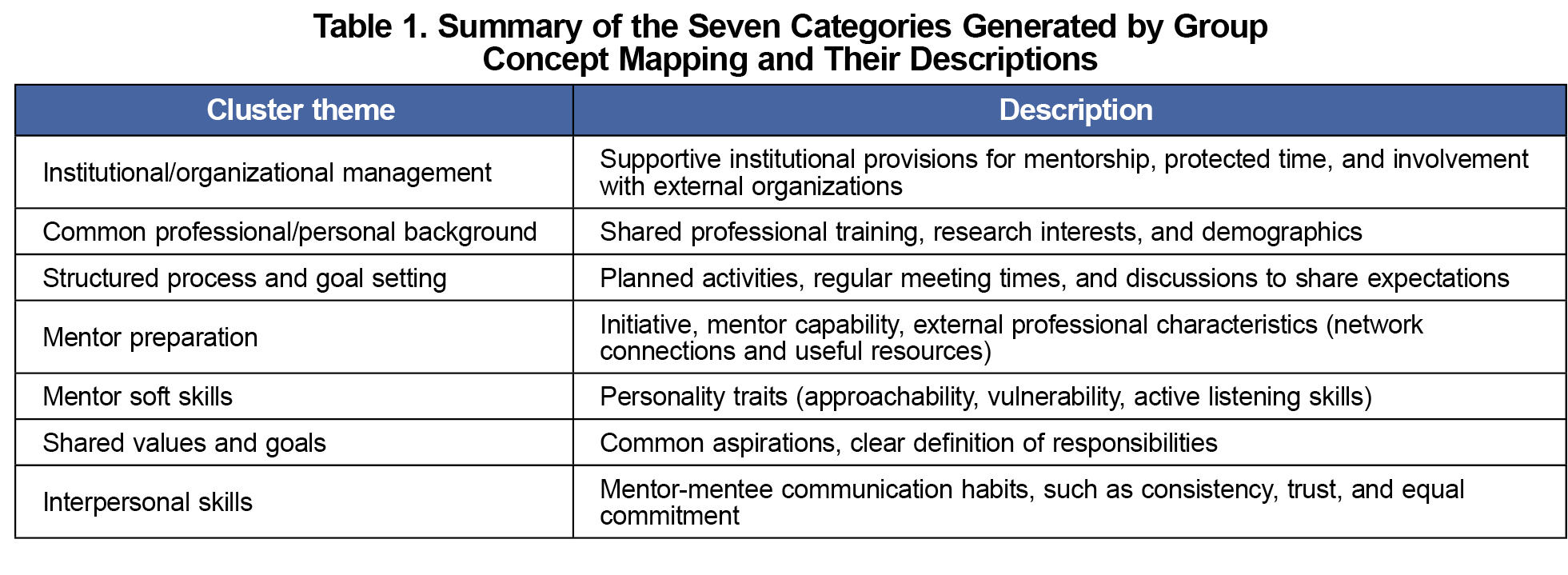

Due to scheduling constraints required for GCM sessions, eight NFS participants (five mentors, three mentees) participated in the GCM session. Professionals included four physician faculty members, one behavioral science faculty member, and three medical educators. Excluding duplicates, participants generated 57 statements. The seven categories were labeled by researchers based on common themes, displayed as a cluster map in Figure 1, and summarized in Table 1. This cluster map’s stress value was 0.2822, which is a metric used in GCM to measure how accurately the cluster map represents the participants’ collective sorting of their statements. For context, a previous meta-analysis of 69 GCM studies found that the average stress value was 0.28, with stress values below 0.39 indicating a low probability of random assortment.11 Institutional/organizational management represents supportive institutional provisions for mentorship, such as protected time or participation in external organizations. Common professional/personal background includes shared professional background, research interests, and demographics. Structured process and goal setting represents planned activities, such as regular meetings and sharing expectations. Mentor preparation describes the mentor’s ability to guide mentees toward their desired goals and aspirations, as well as external professional characteristics such as network connections. Mentor soft skills emphasizes personality traits, such as approachability and listening skills. Shared values and goals encompasses common aspirations and a clear definition of responsibilities. Interpersonal skills reflects mentor-mentee communication habits, such as consistency, trust, and equal commitment.

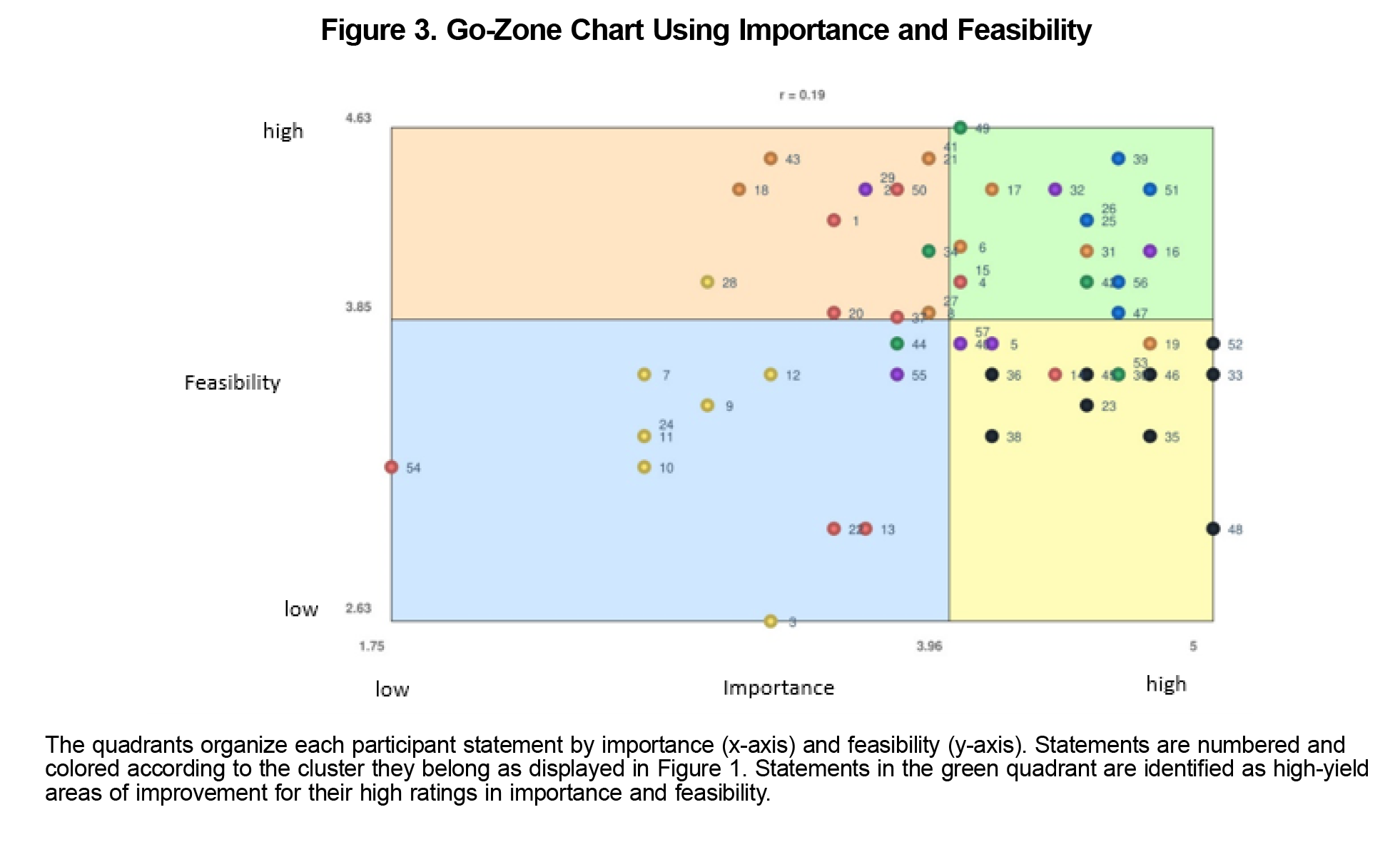

Interpersonal skills, mentor soft skills, and mentor preparation were rated the most highly in importance. Structured processes, mentor soft skills, and mentor preparation were rated highest in feasibility (Figure 2). The largest disparities between current presence and importance were found in interpersonal skills (rating difference 0.68), mentor soft skills (rating difference 0.68), and mentor preparation (rating difference 0.52). Figure 3’s go-zone chart—a visual representation comparing importance and feasibility rankings—contains statements rated highly in both criteria in its green quadrant to indicate high-yield areas for improvement. These statements mostly reflected mentor soft skills, mentor preparation, and shared values and goals. Among rankings for feasibility, structured processes and goal setting was rated the most highly yet displayed lower ratings in current presence rankings (Figure 2).

The components of mentorship most highly rated in importance reflected relational aspects of mentorship, which is consistent with previous studies of mentorship in medicine.12 Relational categories also displayed the largest disparities when compared to rankings in current presence, which may reflect large variations in experience and personality between matched mentors and mentees. Although interpersonal skills were rated highly in importance, they were perceived as among the lowest in feasibility, which may pose unique challenges to improving this high-priority item. Despite this finding, the NFS program has increased its emphasis on mentorship and networking, which can be expected to enhance the relationships formed in the program. Creating optimal mentor-mentee matches based on personality, demographic concordance, and mentor training initiatives also may improve the mentorship experience effectively.

Limitations of this study include a small sample size and therefore a potentially nonrepresentative sample, especially given the slight overrepresentation of mentors (five mentors and three mentees). However, the cluster map’s low stress value (0.2822) demonstrates consistency in the sorted responses by study participants. Moreover, the final participant count of eight is just under the minimum of 10 sorters.

These findings demonstrate the importance of various components of mentorship, from institutional factors to relational aspects, that collectively develop avenues for advising and career guidance. Nevertheless, further studies to assess the characteristics of successful mentorship may benefit from a larger sample size, evaluation of measurable achievements from NFS participants, and inclusion of participants from STFM’s other extended advising programs.

References

- Henry-Noel N, Bishop M, Gwede CK, Petkova E, Szumacher E. Mentorship in medicine and other health professions. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(4):629-637. doi:10.1007/s13187-018-1360-6

- Amonoo HL, Barreto EA, Stern TA, Donelan K. Residents’ experiences with mentorship in academic medicine. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(1):71-75. doi:10.1007/s40596-018-0924-4

- Riley M, Skye E, Reed BD. Mentorship in an academic department of family medicine. Fam Med. 2014;46(10):792-796. https://www.stfm.org/familymedicine/vol46issue10/Riley792

- Farkas AH, Bonifacino E, Turner R, Tilstra SA, Corbelli JA. Mentorship of women in academic medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1,322-1,329. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04955-2

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. About the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Accessed February 22, 2023.https://www.stfm.org/about/about/aboutstfm

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. New Faculty Scholars program. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://stfm.org/awardsscholarships/scholarships/newfacultyscholarsprogram/overview

- Jackson KM, Trochim WMK. Concept mapping as an alternative approach for the analysis of open-ended survey responses. Organ Res Methods. 2002;5(4):307-336. doi:10.1177/109442802237114

- Concept Systems Incorporated. The Concept System groupwisdom (Build 2022.24.01). https://www.groupwisdom.tech

- Rosas SR. Group concept mapping methodology: toward an epistemology of group conceptualization, complexity, and emergence. Qual Quant. 2017;51(3):1,403-1,416. doi:10.1007/s11135-016-0340-3

- Rosas SR, Ridings JW. The use of concept mapping in measurement development and evaluation: application and future directions. Eval Program Plann. 2017;60:265-276. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.016

- Rosas SR, Kane M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35(2):236-245. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003

- Joe MB, Cusano A, Leckie J, et al. Mentorship programs in residency: a scoping review. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(2):190-200. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00415.1

There are no comments for this article.