Introduction: Currently there is a primary care physician shortage in the United States, and this shortage is expected to worsen into the foreseeable future. In 2023, only 7.5 % of US allopathic graduates entered family medicine (FM) residencies. Opportunities to create increased interest in family medicine as a career choice and address hidden curriculum messages in career choice must be explored to address shortages in family medicine.

Methods: A 5-day inpatient experience with family medicine residents on a family medicine inpatient service was implemented during a required third-year core medical student clerkship in family medicine. Students who participated in this clerkship change were invited to complete a survey on how this experience altered their perceptions on the roles of family medicine physicians in inpatient medical care, intrapartum care, and care of the newborn, and how it affected their view of FM as a career choice.

Results: Of the eligible students, 34% completed the survey. Participating in the FM inpatient experience significantly enhanced students’ perceptions about the depth of knowledge and skill needed for the specialty, increased students’ respect for the specialty, and contradicted students’ perceptions about the complexity of cases treated in the specialty.

Conclusion: Adding an inpatient component to a third-year FM clerkship experience can significantly change the perceptions of medical students about the specialty of FM. Brief inpatient exposure to medical students has an impact on hidden curriculum messaging about family medicine.

The United States has a primary care physician (PCP) shortage that is projected to worsen.1 A mismatch in the number of medical students graduating from medical school in the United States and those who seek further training in family medicine (FM) residencies continues. In 2023, only 7.5 % of graduates of US allopathic schools matched into FM.2 US medical schools have been called to graduate classes to reach a national goal of 25% of US medical students choosing FM. 3

Medical students’ choice of specialty training is complex.4,5 Age and gender are associated with primary care as a specialty choice.6 A curricular requirement for a third year primary care clerkship, increased overall time spent in an FM clerkship, and longitudinal primary care experience correlate positively with students’ choice of primary care.6,7 Positive clinical exposure has been demonstrated to be a significant factor in students’ choice of specialty.8 A hidden curriculum related to the value of family medicine also contributes to student choice.9 Specialty disrespect has been identified as one of the elements of the hidden curriculum that negatively affects FM.10 No literature has described the impact or response to incorporating an inpatient FM experience on students’ perception of FM.

To evaluate the impact of a brief inpatient experience on students’ perception of FM, we surveyed clerkship students who had participated in an inpatient FM experience as part of their required third-year FM clerkship.

The Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine (WMed) FM clerkship is a 7-week, required, third year clerkship located in community physician offices. As a curriculum innovation, students from the class of 2021 rotated on the FM residency inpatient service (FMS) for 5 days. FMS included inpatient adults, FM obstetrics, and care of newborns.

We sent a follow-up survey to the WMed Class of 2021. Participants were eligible to complete the survey if they had completed the inpatient experience as part of their FM clerkship. We used REDCap software (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) to securely capture and store the data. One reminder email was sent 2 weeks following the initial invitation.

The 8-question, retrospective, pre/post survey instrument captured participant eligibility, career plans, demographics, impact of the inpatient FM experience on the perceptions of FM and inpatient roles of FM physicians, and whether the inpatient experience should continue to be part of the FM clerkship.11 We developed the survey using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with 3 labeled as “neutral.” The instrument was informed by a review of the literature with face validity confirmed by testing with FM residents. We conducted a one-sample t test using SPSS software version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) to compare student responses against the neutral value. The WMed Insitutional Review Board approved the study.

There were 78 students in the class of 2021 cohort. Of these students, 64 had completed the inpatient experience and were eligible to complete the survey. Fourteen students in the class cohort were unable to participate in the inpatient experience due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The response rate was 34% of the eligible students (n=22).

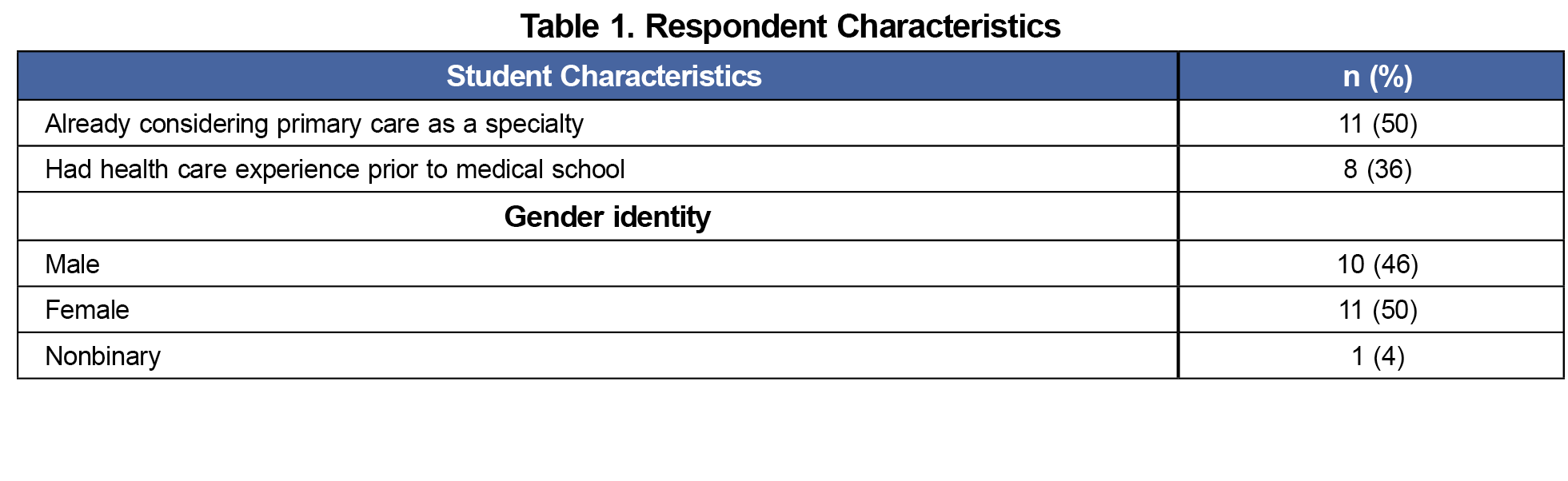

Information on students’ career intentions, their experiences in health care, and their gender identity–factors thought most likely to influence their responses on the survey—were not significant (Table 1).

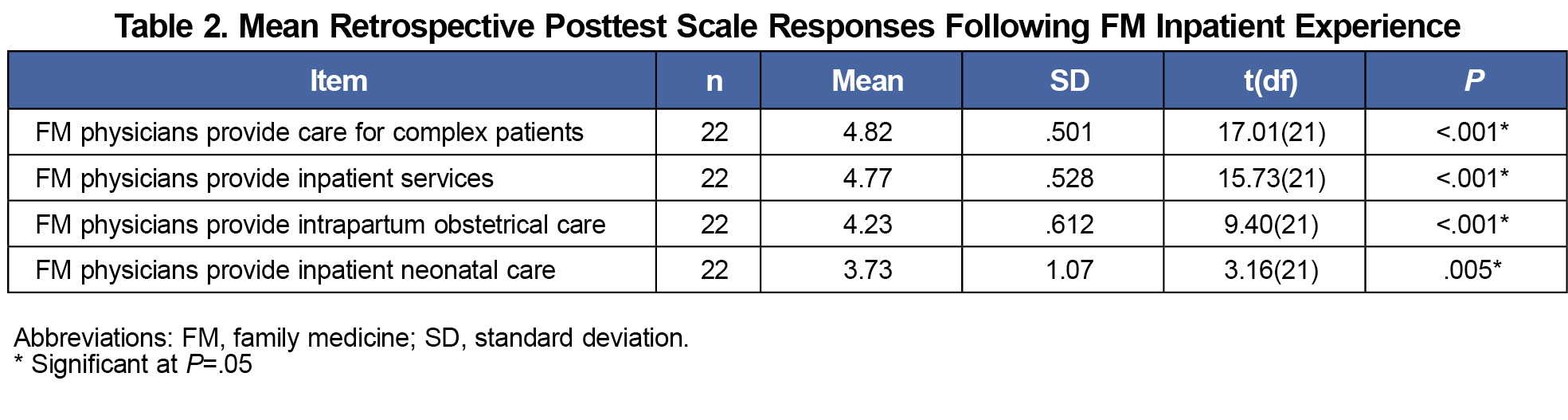

Prior to their inpatient experience, 13 of 22 students (59%) were not aware of/unsure of the extent to which FM physicians provided care for complex patients; 19 of 22 students (86%) were not aware of/unsure of the role of FM physicians in the inpatient setting. Fourteen of 22 (64%) and 19 of 22 (86%), respectively, were not aware of/unsure of FM physicians’ inpatient care of obstetrical patients or newborns. Following the inpatient experience, there were statistically significant differences, and most students agreed they had an improved understanding of the level of complexity of patient care (95%, P<.001), inpatient medicine (95%, P<.001), obstetrical (91%, P<.001) and neonatal care (64%, P=.005) provided (Table 2).

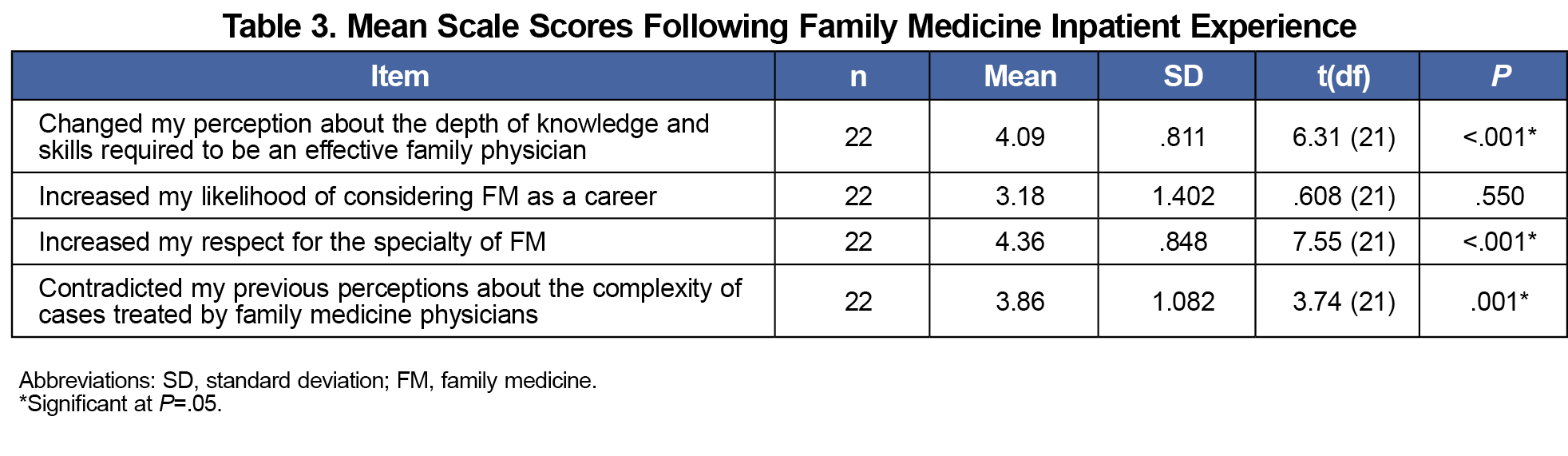

Several significant changes were seen in student perceptions of FM after participating in FMS (Table 3). Eighteen of 22 students (82%, P<.001) reported a change in their perception about the depth of knowledge and skills required to be an effective FM physician (Table 2). The majority (86%, P<.001) agreed that the experience increased their level of respect for the specialty, and most (68%, P=.001) thought the experience directly contradicted their previous perceptions. There was no significant difference in terms of increasing students’ likelihood of pursuing FM as a specialty, even among students who were already planning a career in primary care. None of the responding medical students recommended discontinuing the inpatient experience.

Medical students in our sample reported significant positive changes in their overall perception of FM. This included an increased level of respect for FM physicians and the complexity of care family physicians provide, in addition to an increased student awareness of the breadth of care that FM physicians provide. Although FM continues to be identified by medical students as the most disrespected specialty,10 this brief experience had a positive impact on student perceptions.

Students develop perceptions about family medicine and its alignment with their own careers.9 Changing this narrative will involve multiple strategies,12 one of which is increasing exposure for students to the breadth of family medicine. Given the change evident from a brief exposure to inpatient family medicine, adding inpatient family medicine experiences may be an important addition to these efforts to inform students and counter the impacts of the hidden curriculum.

As survey-based research, our data represent perceptions at a single point in time at a single institution. Although the sample was small, the changes were highly significant. Further long term and multisite studies are needed to determine the persistence of this effect.

References

- IHS Markit Ltd. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034. Washington D.C.; 2021.

- National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2023 Main Residency Match. NRMP; 2023.

- Prunuske J. America Needs More Family Doctors: The 25x2030 Collaborative aims to get more medical students into family medicine. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(2):82-83.

- Scott I, Gowans M, Wright B, Brenneis F. Stability of medical student career interest: a prospective study. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1260-1267. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826291fa

- Mutha S, Takayama JI, O’Neil EH. Insights into medical students’ career choices based on third- and fourth-year students’ focus-group discussions. Acad Med. 1997;72(7):635-640. doi:10.1097/00001888-199707000-00017

- Bennett KL, Phillips JP. Finding, recruiting, and sustaining the future primary care physician workforce: a new theoretical model of specialty choice process. Acad Med. 2010;85(10)(suppl):S81-S88. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4bae

- Pfarrwaller E, Sommer J, Chung C, et al. Impact of interventions to increase the proportion of medical students choosing a primary care career: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1349-1358. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3372-9

- Scott I, Gowans MC, Wright B, Brenneis F. Why medical students switch careers: changing course during the preclinical years of medical school. Can Fam Physician. 2007 Jan;53(1):95, 95:e.1-5, 94.

- Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69(11):861-871. doi:10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001

- Alston M, Cawse-Lucas J, Hughes LS, Wheeler T, Kost A. The persistence of specialty disrespect: student perspectives. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2019;3:1. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2019.983128

- Bhanji F, Gottesman R, de Grave W, Steinert Y, Winer LR. The retrospective pre-post: a practical method to evaluate learning from an educational program. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(2):189-194. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01270.x

- Pfarrwaller E, Sommer J, Chung C, et al. Impact of interventions to increase the proportion of medical students choosing a primary care career: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1349-1358. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3372-9

There are no comments for this article.