Opioid use disorder (OUD) rates have increased over the past 2 decades, constituting a public health emergency affecting approximately 2 million people in the United States. 1,2 Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) treatments, including methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone, have been shown to be safe and highly effective.2 As of 2019, less than one-quarter of those with OUD received treatment with medications.3 The expansion of addiction treatment into primary care has previously been shown to be an effective solution to bridge this significant care gap and reduce overdose mortality.4 Our study took place in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, which reported 20,000 overdoses between of January 2018 and February 2022.5-7 In this study, we aimed to highlight various barriers that impact patients’ ability to obtain treatment for OUD and maintain their treatment progress.

LEARNER RESEARCH

Evaluating Barriers to Opioid Use Disorder Treatment From Patients’ Perspectives

Cecilia M.T. Nguyen* | Grace Kubiak* | Neil Dixit* | Staci A. Young, PhD | John R. Hayes, DO

PRiMER. 2024;8:11.

Published: 2/19/2024 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2024.458349

Introduction: Utilizing medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD) is both highly effective and unfortunately underutilized in the US health care system. Stigma surrounding substance use disorders, insufficient provider knowledge about substance use disorders and MOUD, and historical lack of physicians with X-waivers to prescribe buprenorphine contribute to this underutilization. Our study aimed to elucidate barriers to accessing MOUD in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Methods: We conducted semistructured interviews with patients receiving MOUD at a family medicine residency program in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using the qualitative analysis Framework Method. Researchers in our team reviewed transcripts, coding for specific topics of discussion. Coded transcript data were then sorted into a matrix to identify common themes.

Results: Interviews with 30 participants showed that motivations to seek treatment appeared self-driven and/or for loved ones. Eighteen patients noted concerns with treatment including treatment denial and efficacy of treatment. Housing instability, experiences with incarceration, insurance, and transportation were common structural barriers to treatment.

Conclusions: Primary drivers to seek treatment were patients themselves and/or loved ones. Barriers to care include lack of effective transportation, previous experience with the carceral system, and relative scarcity of clinicians offering MOUD. Future studies may further explore effects of structural inadequacies and biases on MOUD access and quality.

Study Setting and Design

This study took place at a family medicine residency program in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, which operates a dedicated “MOUD clinic” 1 day per week. We conducted semistructured, 10-minute interviews with patients receiving MOUD between July 2021 and May 2022. This qualitative research method allowed for open-ended data collection with insight into patient thoughts, motivations, sociocultural considerations, and overall experiences. This study was approved by the Ascension Health System Institutional Review Board prior to study activities, including an informed verbal consent process.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Inclusion criteria included individuals: (1) currently receiving OUD treatment, (2) aged 18 years or older, and (3) English-speaking. Convenience sampling was utilized by approaching patients during MOUD appointments. Most patients were recruited in-person while one interviewee participated virtually. The objective of the study was explained to patients by the physician or medical student working with the patient, and patients were verbally invited to participate in the study. Participation was nonincentivized. Participants were assured that their decision regarding participation would not affect their medical care. Patient identifiers were omitted from the data collection.

Data Analysis

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by researchers. The established qualitative analysis of semistructured interviews, “Framework Method,” was utilized to code and sort transcripts.8,9 To minimize the risk of group bias, each transcript was reviewed and coded independently by at least two researchers. Coded transcript data was then sorted into an excel matrix document. To minimize the risk of an individual bias on analysis, all research team members reviewed the matrix document and generated a consensus of data interpretation.

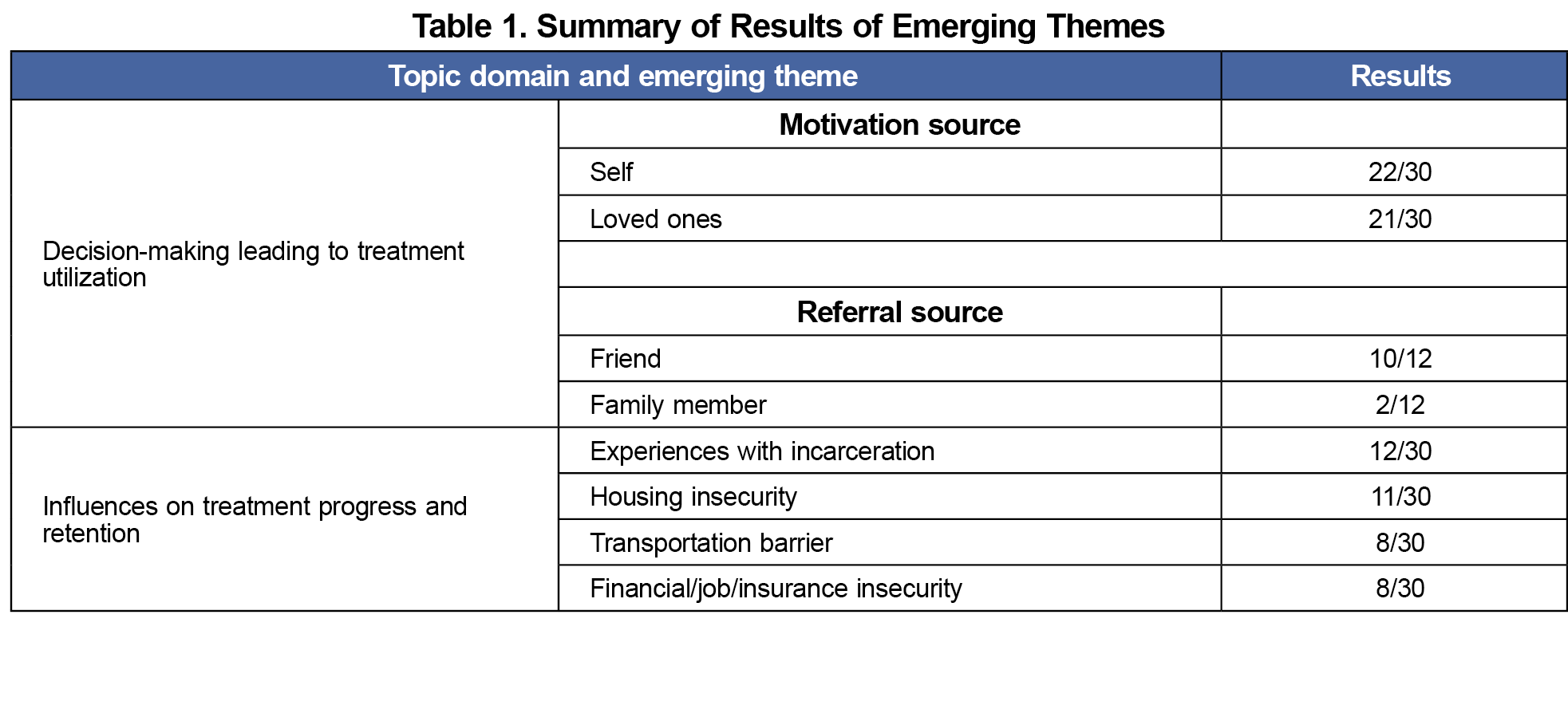

A sample of 30 patients participated in this study. We observed the following themes emerge within two domains: (1) decision-making leading to treatment utilization, and (2) influences on treatment progress and patient satisfaction (Table 1).

Decision-Making Leading to Treatment Utilization

The patient decision-making process encompasses values, beliefs, influences, and choices leading to their choice to start or continue MOUD. Participants were asked about their primary motivations to seek treatment, decision to come to this clinic, and initial treatment concerns.

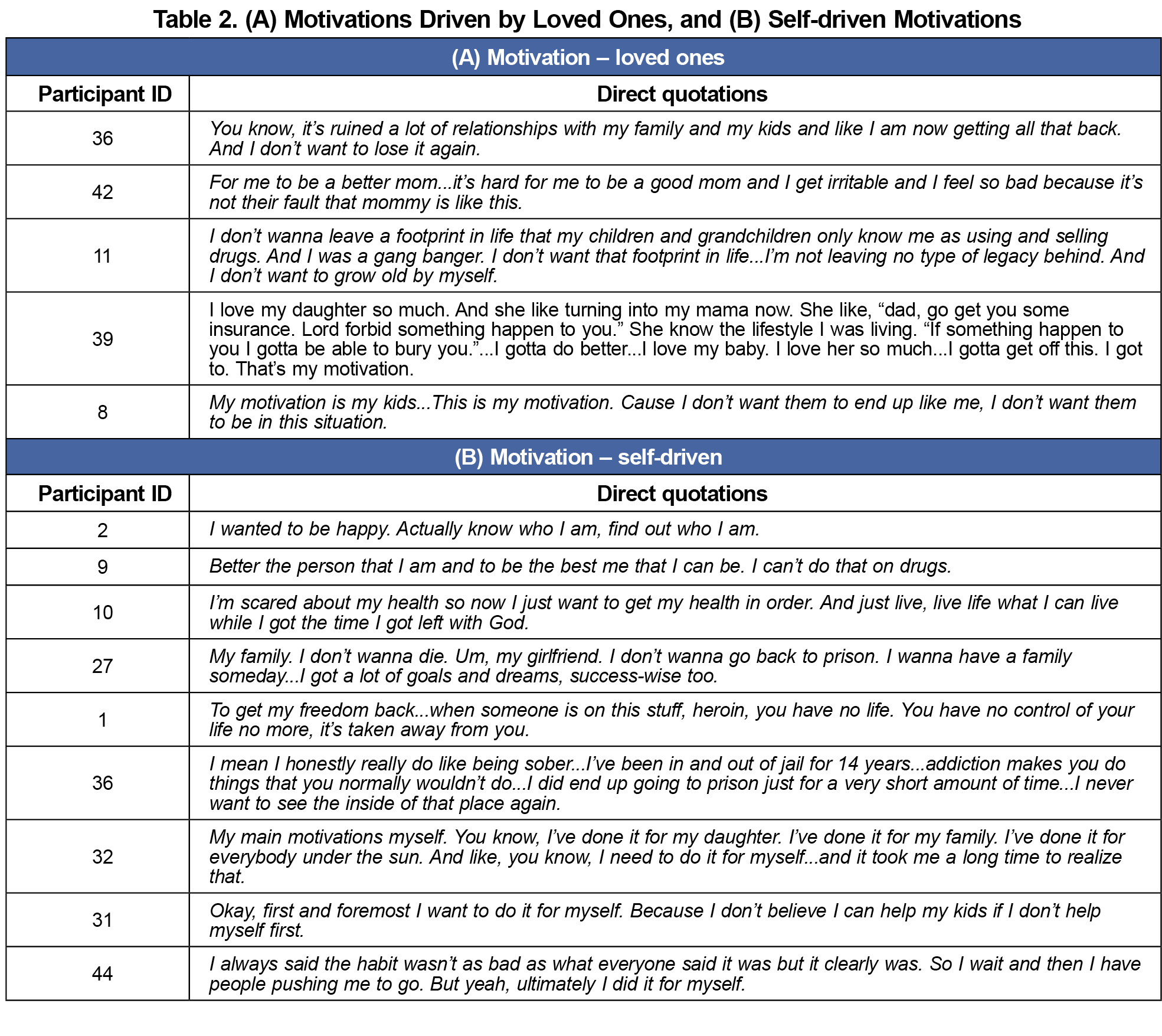

Motivations. Some patient motivations involved the desires to improve relationships with their children and loved ones, as well as setting a positive example for their children (Table 2). A larger majority emphasized being self-driven while seeking care. Participants noted seeking care to repair relationships but that this motivation was not enough to succeed and emphasized the importance of readiness to change for themselves (Table 2).

Connections to the Clinic. Many participants endorsed knowing a friend or family member who is currently receiving or had prior treatment at this same clinic. A smaller portion of participants mentioned a referral by another physician or community organization, while others found the clinic online.

COVID-19 Impacts. Six participants discussed the impact of COVID-19 on their treatment, focusing on social interactions. Two participants referenced the negative aspects of social isolation. Another referenced challenges with virtual therapy as a person with visual and hearing impairments. Two participants stated that the isolation was a positive as it prevented them from interacting with people supporting their drug use. The remaining participant discussed an increased urge to use during the pandemic as well as related cocaine use.

Influences on Treatment Progress and Patient Satisfaction

Participants were also asked about prior treatment experiences, specifically what has and has not worked for them in the past. Additionally, participants were asked about social stressors that challenged their treatment progress.

Previous Treatment Experience. Multiple patients spoke about prior treatment attempts. Interviewees highlighted varying methods of cessation including methadone clinics, inpatient treatment, and attempts at self-cessation. At least six participants endorsed ten or more treatment attempts, though this number is likely higher as some patients did not report previous number of attempts. Of note, several participants cited negative experiences with clinicians a contributing factor to unsuccessful treatment attempts.

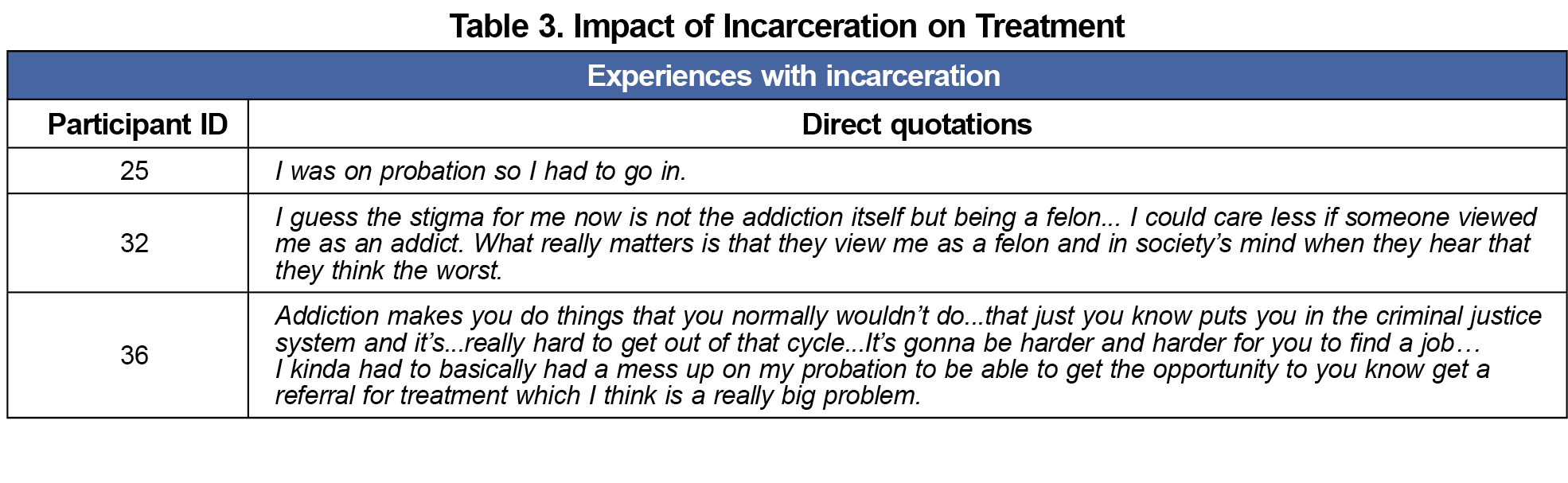

Experience With Incarceration. Many interviewees discussed their history with incarceration, reporting avoiding future interactions with the carceral system as a driving factor for treatment, while others were mandated treatment as a part of probation (Table 3). One patient described their past incarceration as a barrier to care, sharing how the stigma of a criminal record interferes with their ability to find a job, afford necessities, and continue treatment. Participants also discussed incarceration as a time of forced sobriety and an experience that interfered with ongoing treatment.

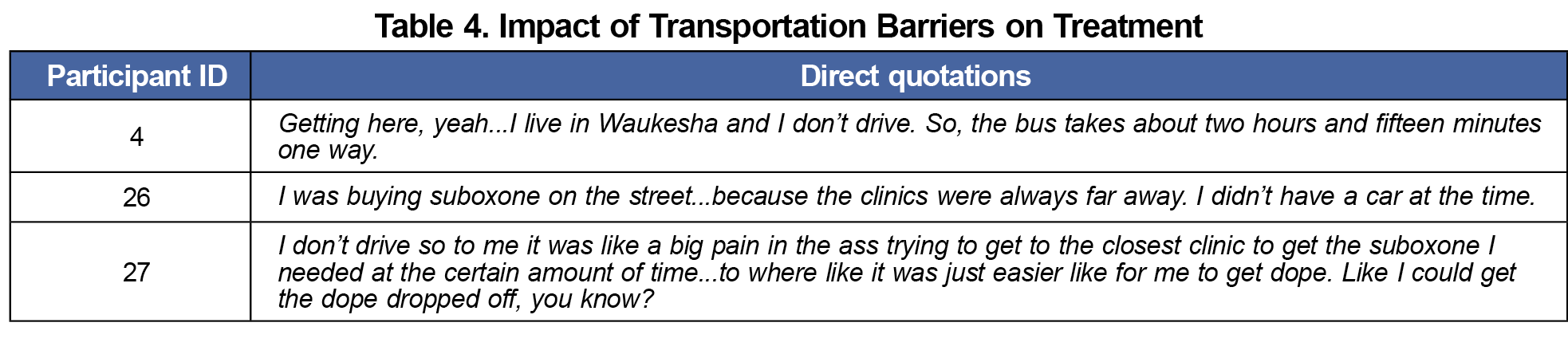

Socioeconomic Influences. Many participants mentioned experience with housing insecurity. Of these individuals, most endorsed having unstable housing currently and with concurrent financial strain, job instability, or lack of insurance. Some attributed housing-related stress to living with people actively using. Patients also discussed transportation inadequacy as a challenge to receiving care or affecting treatment progress (Table 4).

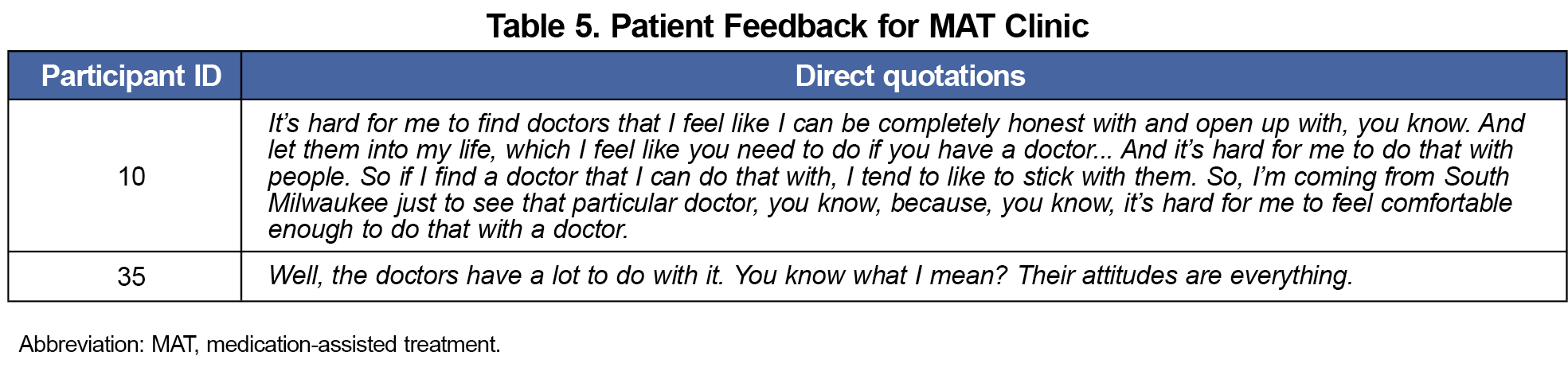

Characteristics of a Family Medicine Residency MOUD Clinic. Of note, four participants spoke about characteristics of the clinic that have contributed to their positive experience. These perspectives can inform clinicians how the attitudes of providers and staff can create environments conducive to success in treatment (Table 5).

In our study, the primary drivers to seek treatment were the patients themselves and their loved ones rather than any external influences. Recommendations from family and friends often prompted patients to seek treatment at the clinic, suggesting the efficacy of word-of-mouth and patient handouts as community-based approaches to recruit patients and improve utilization.

Our study also highlighted the impacts housing instability, transportation availability, and incarceration can have on treatment progress. Felonies and incarceration for drug use make housing and employment difficult to secure.11-13 Patients without employment or housing are often reliant on unreliable public transit or shared rides. The transportation burden is exacerbated as patients must travel long distances to find care. The barriers identified in this study resonate with previous work discussing the impact of stigma and barriers on accessing substance use disorder treatment. 11-13 Increasing the number of clinicians that prescribe MOUD via education in residencies and medical schools has been shown to significantly improve availability of quality treatment.4 Working closely with clinical social workers to link patients to housing, legal aid, and employment services could improve treatment outcomes.2,5

Limitations of this study include lack of a broad sampling pool, a single recruitment site, and the influence of mentioned barriers to care on study recruitment. Many potential participants missed appointments or chose not to participate because of needing to catch a bus or utilizing unreliable medical transport services. The barriers reported in this study are likely underreported as participants were actively engaged in care when discussing their barriers. Previous studies have indicated the role of identities such as gender, sexuality, and parenthood status in accessing MOUD; given our study highlighted loved ones as a major motivation in treatment, exploring social identity (eg, demographics of race, gender, zip code, or income level) and family structure could have further elucidated patient experiences in addiction treatment.14 Additionally, despite following a rigorous qualitative analysis process, it is still possible that bias influenced the coding and thematic analysis process.

This study highlights the necessity of incorporating the thoughts, beliefs, and experiences of people with OUD into primary care addiction medicine. In the face of a worsening opioid epidemic, primary care clinicians must overcome the entrenched stigma against treating addiction.15 We hope that health care professionals have gained insight and perspective from our patient’s stories and feel inspired to provide essential care for this vulnerable patient population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank participants for sharing their experiences and the staff and residents at Ascension Columbia St Mary’s Family Center for their facility and assistance with participant recruitment. They thank the Scholarly Project Program and Urban & Community Health Pathway Program at the Medical College of Wisconsin Medical School for their support, mentorship, and encouragement for this project.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Corrigan PW, Nieweglowski K. Stigma and the public health agenda for the opioid crisis in America. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;59:44-49. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.06.015

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment

- Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019.

- Leiser A, Robles M. Expanding buprenorphine use in primary care: changing the culture. Perm J. 2022;26(2):177-180. PMID:35933665 doi:10.7812/TPP/21.203

- Preventing and treating harms of the opioid crisis. Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Feb 2020, P-02605. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p02605.pdf

- Milwaukee County. Milwaukee County Overdose Dashboard: Overdose data. Last updated January 23, 2024. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://county.milwaukee.gov/EN/Vision/Strategy-Dashboard/Overdose-Data.

- Division of Care and Treatment Services. Wisconsin Mental Health and Substance Use Needs Assessment 2019. Wisconsin Department of Health Services. P-00613; Sept 2020. Accessed February 4, 2024. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p00613-19.pdf

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):117. PMID:24047204 doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7(2):e000057. doi:10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(1):39-50. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x

- Fox AD, Maradiaga J, Weiss L, Sanchez J, Starrels JL, Cunningham CO. Release from incarceration, relapse to opioid use and the potential for buprenorphine maintenance treatment: a qualitative study of the perceptions of former inmates with opioid use disorder. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10(1):2. doi:10.1186/s13722-014-0023-0

- Iguchi MY, London JA, Forge NG, Hickman L, Fain T, Riehman K. Elements of well-being affected by criminalizing the drug user. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(Suppl 1)(suppl 1):S146-S150.

- Moore LD, Elkavich A. Who’s using and who’s doing time: incarceration, the war on drugs, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9)(suppl):S176-S180. doi:10.2105/AJPH.98.Supplement_1.S176

- Bakos-Block C, Nash AJ, Cohen AS, Champagne-Langabeer T. Experiences of parents with opioid use disorder during their attempts to seek treatment: a qualitative analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24):16660. doi:10.3390/ijerph192416660

- Madden EF, Prevedel S, Light T, Sulzer SH. Intervention stigma toward medications for opioid use disorder: a systematic review. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56(14):2181-2201. doi:10.1080/10826084.2021.1975749

Lead Author

Cecilia M.T. Nguyen*

Affiliations: Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

Co-Authors

Grace Kubiak* - Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

Neil Dixit* - Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI | * Authors Nguyen, Kubiak, and Dixit contributed equally to this study.

Staci A. Young, PhD - Department of Family & Community Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwuakee, WI

John R. Hayes, DO - Medical College of Wisconsin, Department of Community and Family Medicine, Milwaukee, WI

Corresponding Author

John R. Hayes, DO

Correspondence: Department of Family & Community Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 W. Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226

Email: jrhayes@mcw.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.