Food insecurity (FI) is “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food.”1 About 11% of American households indicated that they “sometimes or often did not have enough to eat” in 2022 compared to 8% in 2021, highlighting this hidden epidemic.2 Increased attention has focused on the importance of primary care physicians’ (PCPs) assessments of a patient’s food security.3 While obstacles to using screening tools for identifying patients with FI have been noted,3 research on patient preferences suggests FI screening is unlikely to damage the patient-physician relationship.4 To date, little is known about provider attitudes toward and experiences with screening.1-4 PCPs may perceive FI as a difficult topic to address in health care encounters, and patient stereotypes about FI may result in at-risk patients being unidentified. This pilot study sought to explore the range of provider perspectives on how providers decide to screen patients for FI, effective strategies for communicating about FI, and barriers that impact screening.

LEARNER RESEARCH

Food Insecurity: Physician Perspectives, Screening and Communication

Sally Heaberlin, MD | Kelly Skelly, MD | Marcy Rosenbaum, PhD | Stephanie Bunt, PhD

PRiMER. 2024;8:38.

Published: 7/1/2024 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2024.400838

Introduction: Primary care physicians may perceive food insecurity (FI) as a difficult topic to address in health care encounters, resulting in at-risk patients not being identified. This exploratory study examines physician perspectives on how decisions to screen patients for FI are made, effective FI communication strategies, and barriers to screening.

Methods: Primary care physicians in the statewide, practice-based Iowa Research Network (IRENE) completed a study survey in May 2022 that included structured and open-ended questions regarding their experiences screening for FI. Thematic and descriptive analysis identified common themes in providers’ experiences and perspectives.

Results: Although most physicians responding to the survey indicated that they have observed FI in their patient population, 27% have never observed FI in their practice. Physicians varied in their reasons for deciding to screen, with the most reported reason being “when it comes up in conversation.” Common screening barriers among respondents included limited appointment time and feeling inadequately prepared to connect patients with resources. Respondents noted that negative experiences with FI screening were rare and noted positive experiences, including gratitude from the patient, and building patient-physician trust. Respondents shared normalizing phrases that helped address the additional obstacle of feeling inadequately prepared to assess FI in a tactful manner.

Conclusions: This study explored physicians' experiences with asking patients about FI and provides insight into FI screening gaps, barriers, and opportunities. Better understanding of physician attitudes and practices may help guide and address barriers to more effective and consistent FI screening.

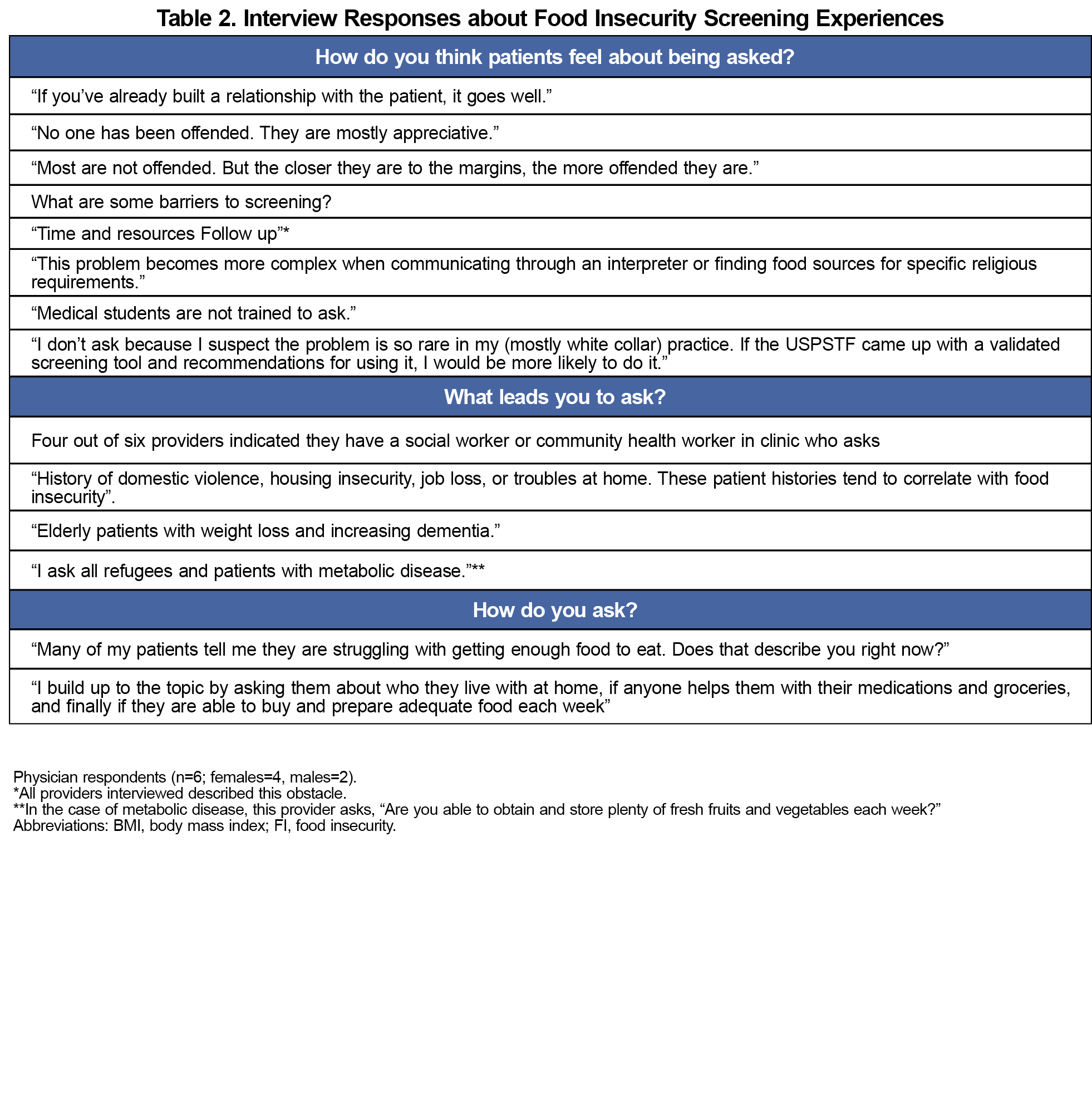

PCPs within the practice-based Iowa Research Network (IRENE), serving 75 of Iowa’s 99 counties, were sent a survey in May 2022 (N=150). The survey included Likert scale and multiple-answer questions regarding: (1) the physician's assessment of observed FI in his/her own practice; (2) if and what prompts the physician to ask patients about FI; and (3) perceived barriers to screening FI. Respondents could also provide open-ended comments about (1) when and who they choose to ask about FI; (2) obstacles in addressing FI with patients; and (3) negative, positive and surprising experiences interacting with patients around FI. Six respondents agreed to be interviewed (Table 2). The study was approved by the University of Iowa’s Institutional Review Board.

Thematic analysis using a phenomenological “editing analysis style” approach5,-7 was used to identify key themes in participants’ responses to the open-ended questions. All responses were reviewed individually by research team members and compared and discussed to identify themes mentioned most frequently.

Thematic analysis of the open-text survey questions was completed to evaluate which themes reflected the perspectives of the population. The qualitative answers were complemented by quantitative analysis of the survey data.

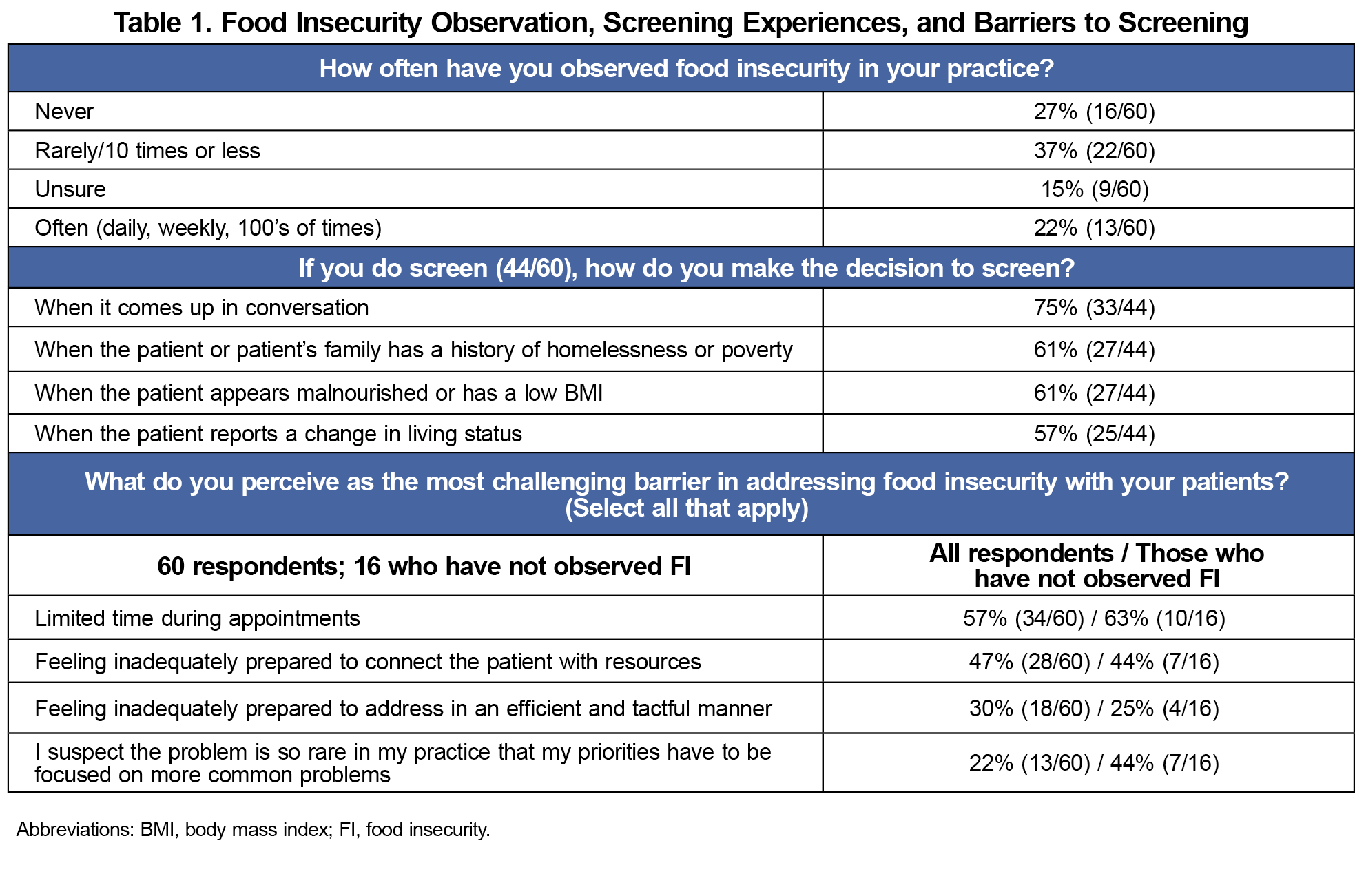

Sixty of the 150 physicians invited completed the survey (40% response rate). Although most physicians surveyed (44/60) have observed FI in their patient population, 27% (16/60) have never observed FI in their practice (Table 1).

Theme I: When and Who Is Screened for FI

Among physicians who have observed FI, some (57%, 25/44) reported having a screening approach built into certain appointment types. Common approaches included having FI in screening questionnaires, particularly for annual visits; questions asked by nurses during well- child exam rooming; or using a social/community health worker who asks. Physicians’ most-reported reason for FI screening was “when it comes up in conversation” (Table 1). For example, physicians noted FI being brought up by a patient or being relevant to their medical condition. Other social determinants of health such as domestic violence, age, or refugee status were noted as triggers for FI screening.

Theme II: Barriers

Perceived FI screening barriers were compared between all respondents and respondents who do not ask about FI (Table 1). The most common screening barrier was limited appointment time. For example, one physician commented, “Moving so fast in clinic that my awareness is not sharp enough.” Additionally, for physicians who do not ask about FI, 44% (7/16) identified feeling inadequately prepared to connect the patient with resources and 44% (7/16) suspected FI was rare in their practice.

Theme III: Experiences

Physician descriptions of experiences asking patients about FI point both to potential benefits and challenges of engaging in these conversations. Respondents noted that negative experiences with FI screening were rare, and included some patients being surprised or offended to be asked, or not being able to connect patients with appropriate resources. Sixty-eight percent (30/44) of those who asked about FI indicated never having a negative experience. Rather, providers noted that asking about FI contributed to deeper, more positive and trusting patient relationships, both in showing patient concern and connecting them with valuable resources (Table 2). Providers also indicated instances where they have been surprised to learn about patient FI issues due to such things as lacking refrigeration, poor vision, financial pressures, or difficulty obtaining food.

While other studies have examined screening tools for identifying patients with FI,3 our research sought to explore physicians' experiences with asking patients about FI and provide insight into FI screening gaps, barriers, and opportunities. With reports of 11% of US households being food insecure, PCPs are likely to encounter several food insecure patients weekly, regardless of the average socioeconomic status of the specific clinic population.2 Despite this statistic, our findings highlight that most study participants consistently do not ask about FI despite that 73% of respondents reported observing FI in their practice. The barrier “I suspect the problem is so rare in my patient population” was more common for those reporting never observing FI. If providers rarely screen patients, they are likely missing FI and health implications.

Physicians identified time as a main obstacle to FI screening. Single-question approaches to screening for health behavior (ie, drug use, physical activity) have shown both validity and time efficiency. 8-10 The necessity of using multiple single-question screens to address distinct SDOH concerns could require significant provider time. Using normalizing phrases identified in our study (Table 2) could address the additional obstacle of feeling inadequately prepared to assess FI tactfully. Most respondents with experience asking about FI reported limited negative experiences and noted positive experiences, such as patient gratitude and increased patient-physician trust.

This exploration of physician attitudes and practices may help address barriers and guide more effective and consistent FI screening. Limitations to this pilot study include that it focused on a single state relying on provider self-reports, so may not be representative of all primary care providers. Future research on provider FI screening encompassing a larger number and greater variety of practice locations is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented at the International Conference on Communication in Healthcare in Glasgow Scotland, September 8, 2022.

References

- Food security in the United States. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Updated October 25, 2022. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/measurement/

- Household pulse survey: food scarcity. US Census Bureau. July 27-Aug 3, 2022. Accessed June 24, 2024. https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/hhp/#/

- Eder M, Henninger M, Durbin S, et al. Screening and interventions for social risk factors: technical brief to support the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;12;326(14):1416-1428. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.12825.

- Kopparapu A, Sketas G, Swindle T. Food insecurity in primary care: patient perception and preferences. Fam Med. 2020;52(3):202-205. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.964431

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research.Sage Publications; 1992.

- Hanson JL, Balmer DF, Giardino AP. Qualitative research methods for medical educators. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(5):375-386. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2011.05.001

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483-488. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

- Rose SB, Elley CR, Lawton BA, Dowell AC. A single question reliably identifies physically inactive women in primary care. N Z Med J. 2008;121(1268):U2897.

- Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1155-1160. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.140

- Gill DP, Jones GR, Zou G, Speechley M. Using a single question to assess physical activity in older adults: a reliability and validity study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):20. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-20

Lead Author

Sally Heaberlin, MD

Affiliations: University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA

Co-Authors

Kelly Skelly, MD - Department of Family Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

Marcy Rosenbaum, PhD - University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA

Stephanie Bunt, PhD - Department of Family Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

Corresponding Author

Sally Heaberlin, MD

Correspondence: University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA

Email: sally-heaberlin@uiowa.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.