Introduction: A level of hesitancy existed among parents when United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved pediatric COVID-19 vaccines were introduced. We explored attitudes, beliefs, and willingness of health care personnel (HCP) as parents to vaccinate children less than 18 years of age.

Methods: We developed a cross-sectional survey for HCPs as parents, including clinical and nonclinical staff, researchers, and trainees at a single academic medical institution. We assessed role categories by vaccination status, willingness to vaccinate their children, and COVID-19 history. We analyzed data via cross tabulation and Pearson correlation to examine relationships across variables.

Results: There were a total of 1,538 research respondents. Nurses had a higher COVID-19 history compared to other roles (29.2%, P<.001). Vaccinated nurses were more likely to vaccinate their children (64.6%, P<.001). There was a significant negative correlation between self-identification as a nurse and willingness to vaccinate themselves (r=-.157, P<.001) or any child (r=-.150, P<.001), and a significant positive correlation among nurses having any COVID-19 history (r=.118, P<.001). Having a positive COVID-19 history was negatively correlated with personal vaccine status (r=-.217, P<.001) and intent to vaccinate any child (r=-.252, P<.001). While 77.8% (n=123) of all nurses with children were vaccinated willingly, 65.8% (n=104) had at least one child vaccinated; 81.3% of willingly vaccinated nurses (n=100) vaccinated at least one child, vs 11.4% (n=4) of nurses who mandated or were unvaccinated themselves.

Conclusions: Nurses were more hesitant to vaccinate themselves than other roles, had higher rates of COVID-19 history, and were more hesitant to vaccinate their children if they were unvaccinated.

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has claimed over a million US lives since December 2019.1,2 In response to this crisis, adult COVID-19 vaccines, including the mRNA and single-dose Janssen vaccine, were developed and rolled out in the United States by December 2020 and February 2021, respectively.2 Soon after the development of adult COVID-19 vaccines, pediatric vaccines were made available. The US Food and Drug Administration issued full approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines for children ages 16 years and older on August 23, 2021. They further issued an Emergency Use Authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for ages 5 to 11 years in fall 2021,3 and children aged 6 months to 4 years in late spring 2022.4

One issue that had become apparent by the time pediatric vaccines were introduced was the level of vaccine hesitancy, with vaccination rates in the United States historically lagging in comparison to other high-income countries.3,5 To facilitate the rollout of pediatric vaccines at our academic medical institution and within the region, we conducted a survey assessing pediatric vaccine acceptance within the population of our health sciences institute, as a quality improvement effort. This exploration built upon previous surveys conducted at our institution prior to when vaccines were available for adults.2,6 Our primary objective was to assess concerns among health care personnel (HCP) that would undermine vaccination efforts for children less than 18 years old. Assessing HCP attitudes, beliefs, and willingness to vaccinate their children under 18 was useful for informing discussions within the institution for vaccination programs and to assess differences within the workforce.

Project Population Setting

The State University of New York Upstate Medical University is an academic medical center located in the Central New York region. The institution had approximately 12,000 employees at the time of the survey.

Survey Development and Administration

We developed a cross-sectional survey designed for parents that was deployed via the REDCap electronic data management tool to HCPs, including clinical and nonclinical staff, researchers, and trainees, between December 13, 2021 and January 14, 2022. Survey validation steps included deployment within a small group of public health and clinical experts (a validation group) to test functionality and content. After modification of the draft instrument, based upon feedback regarding content and usability from the validation group, the survey was sent to all employees through an anonymous link via institutional emails (one invitation and two reminders). Additionally, an icon prompting employees to take the survey was placed on the home screens of computers. As the anonymous internal survey initially intended to inform internal quality improvement efforts, the Institutional Review Board of Upstate Medical University determined the project did not constitute research.

Survey Content

The survey evaluated attitudes, beliefs, sources of information, and willingness to vaccinate children 18 years and under. We included questions on demographic information, occupational role, history of COVID-19 infection, COVID-19 vaccination status, whether participants identified as a parent, intent to vaccinate children between the ages of 0-4 years, 5-11 years, 12-17 years, preferred vaccination site, who influences decisions about their children receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, the decision-maker for their children to get vaccinated, beliefs on natural immunity, children’s prior vaccine history, concerns and hesitancies, barriers, and their stance on school mandating the COVID-19 vaccine. A copy of the survey is available in the STFM Resource Library.7

Analysis

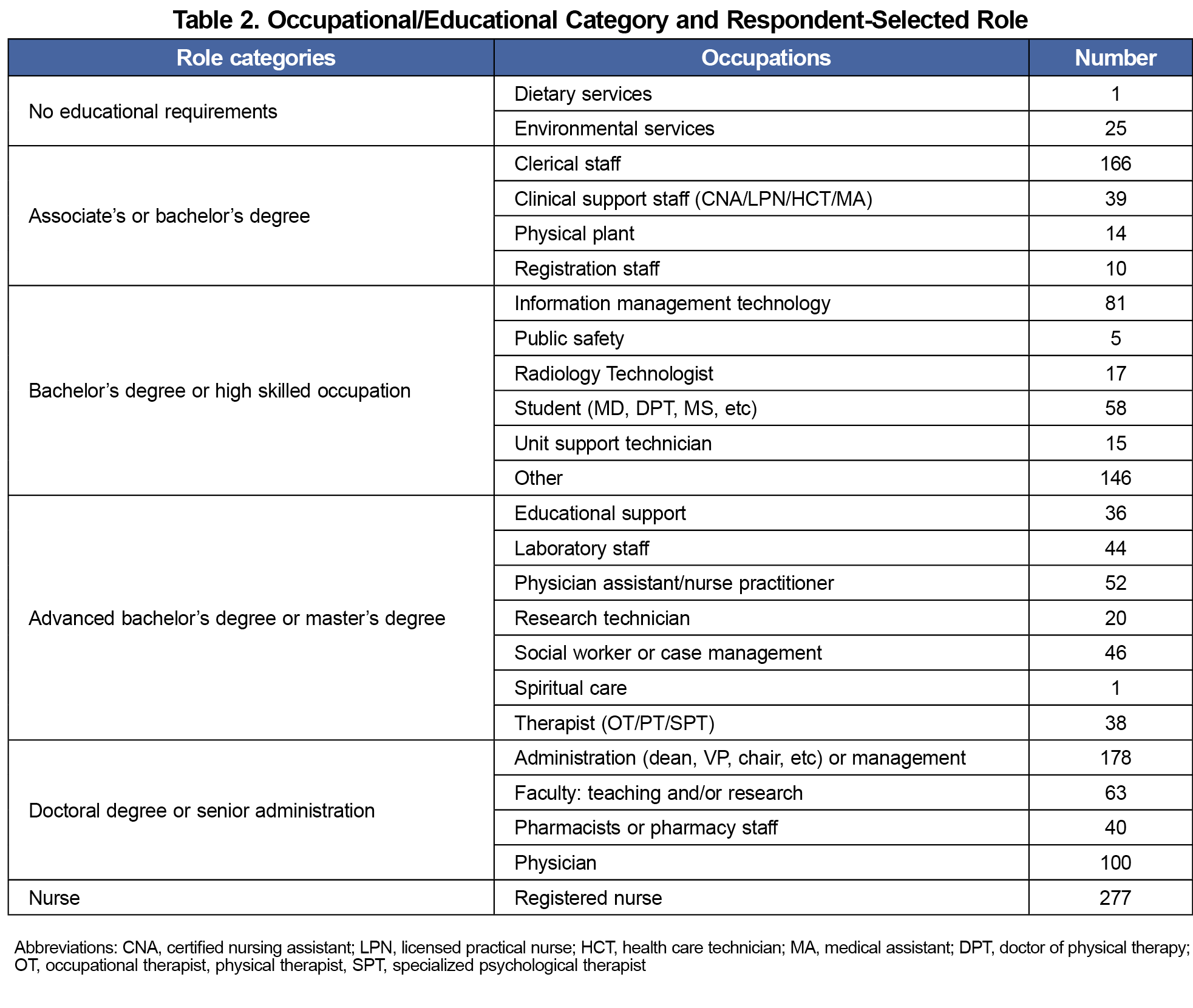

We calculated the distribution of our sample across gender, race, ethnicity, willingness to vaccinate, COVID-19 history, and whether respondents identified as a parent/guardian. We collapsed participants’ roles into six meta categories: no educational requirements, associate’s/bachelor’s, bachelor’s or high-skilled occupation, advanced bachelor’s or master’s, doctoral degree or senior administration, and nursing.

Employees at the institutional site were mandated by New York State to be vaccinated against COVID-19 when adult vaccines became available, and this requirement was in place prior to and during the rollout of pediatric vaccines. Many employees were vaccinated quickly, but some were given an ultimatum to be vaccinated or lose their positions; a small number of employees managed to obtain exemptions for health or religious reasons, but these were exceedingly rare. We therefore examined role categories by vaccination status (willingly vaccinated vs unvaccinated or vaccinated by mandate), willingness to vaccinate their children (yes/no), and COVID-19 history. We then analyzed the data via cross-tabulation with χ2 tests. We also used Pearson correlation to further examine these relationships across variables. Given the overall size of the sample, we utilized P≤.05 as our threshold for statistical significance.

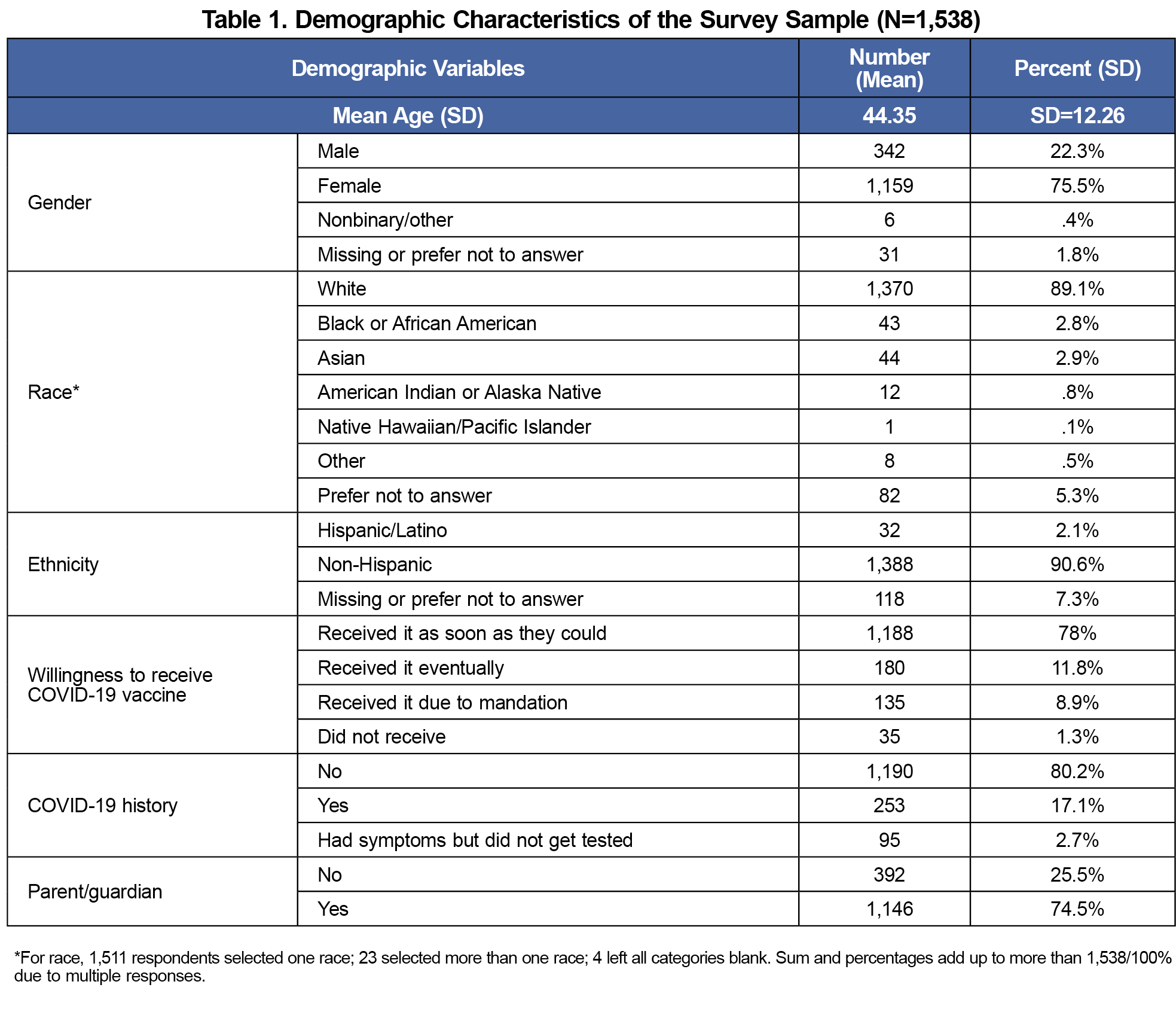

There were 1,538 survey respondents. Not all employees at the institution regularly use email and no incentives were awarded; therefore, the response rate was approximately 15%. Mean age of respondents were 44.35 years (SD=12.26). The majority of respondents were female (75.5%, n=1,159), White (89.1%, n=1,370), and Latinx/Hispanic origin (2.1%, n=32); 74.5% (n=1,146) of respondents were parents or guardians vs 25.5% (n=392) who were not. Table 1 gives additional demographic details of the survey respondents. Additionally, the 24 distinct roles in which participants identified themselves were collapsed into six meta-categories. The alignment of roles and the role categories is shown in Table 2.

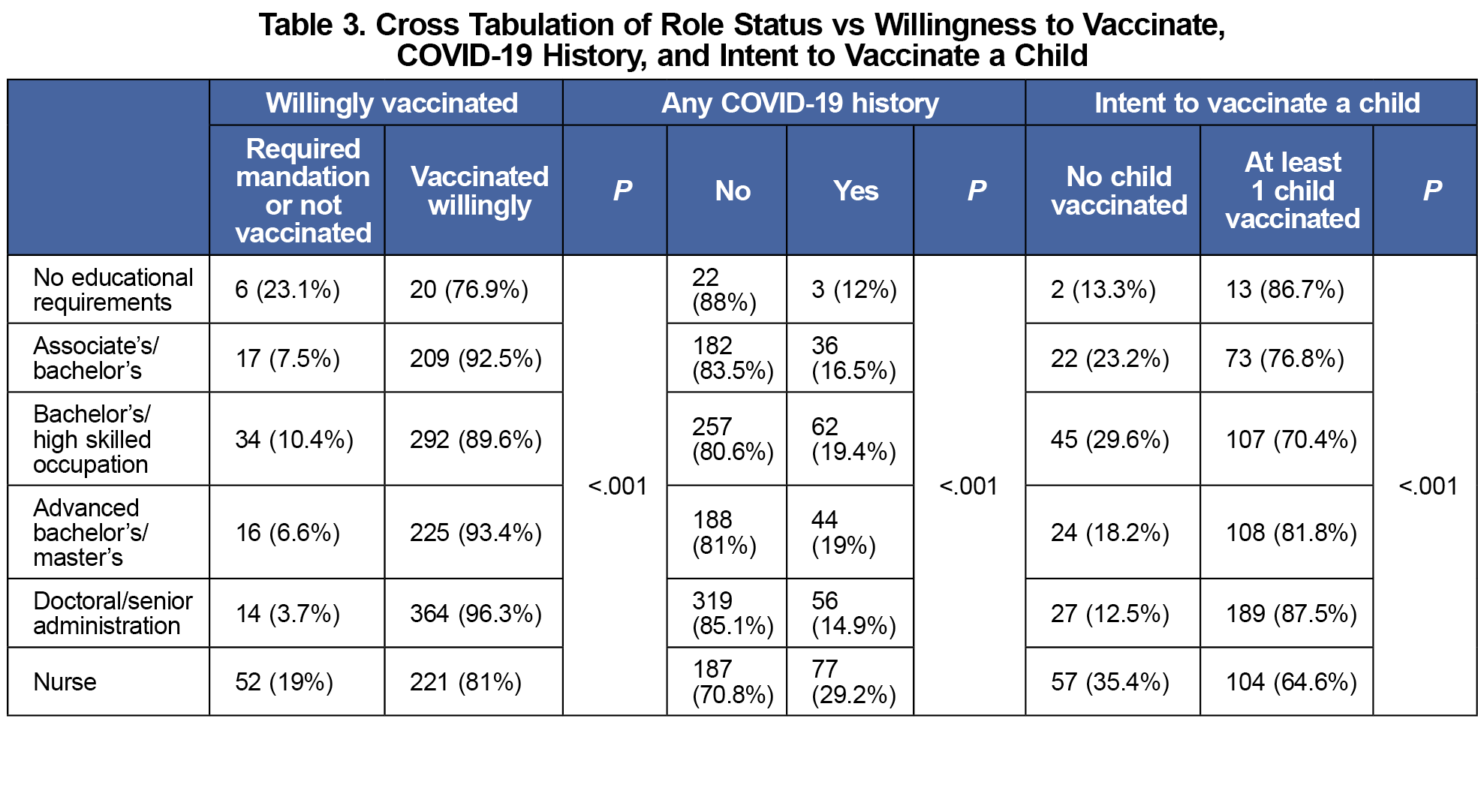

Respondents who were mandated or were unvaccinated were more represented in roles with no education requirements (23.1%) and in nurses (19%) than in other roles (P<.001). Additionally, nurses were more likely to have COVID-19 history compared to other roles (29.2%, P<.001). If nurses were vaccinated, the likelihood of vaccinating their children increased (64.6%, P<.001). Table 3 provides a further breakdown of vaccination status, COVID-19 history, and intent to vaccinate a child by role. While 77.8% (n=123) of all responding nurses with children were vaccinated willingly, 65.8% (n=104) had at least one child vaccinated; 81.3% of willingly vaccinated nurses (n=100) vaccinated at least one child, vs 11.4% (n=4) of nurses who were mandated or were unvaccinated themselves.

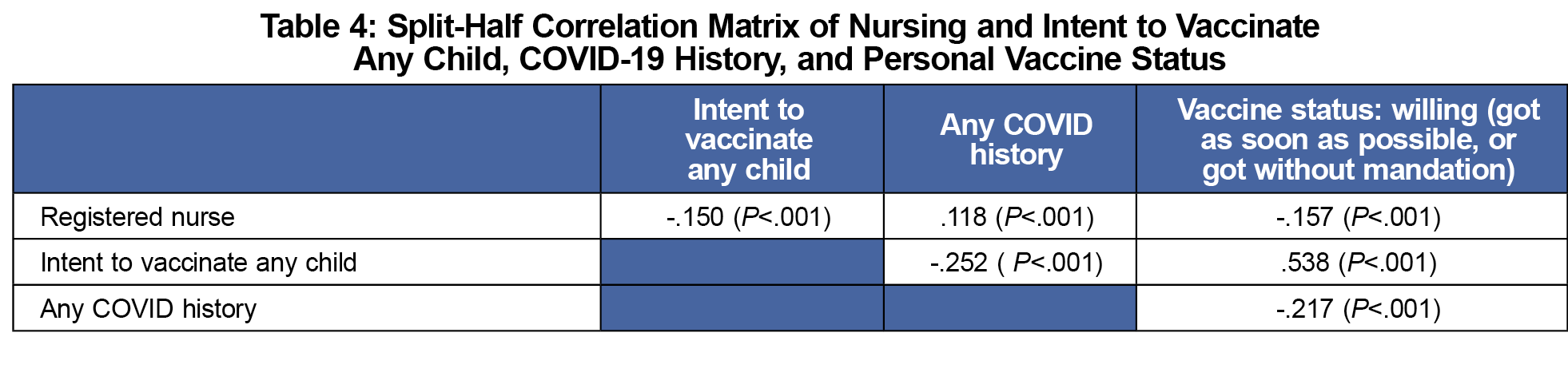

There was a significant negative correlation between self-identification as a nurse and willingness to vaccinate themselves (r=-.157, P<.001) or any child (r=-.150, P<.001), and a significant positive correlation among nurses having any COVID-19 history (r=.118, P<.001). Having a positive COVID-19 history was negatively correlated with both personal vaccine status (r=-.217, P<.001) and intent to vaccinate any child (r=-.252, P<.001). Personal vaccine status was strongly correlated with intent to vaccinate any child (r=.538, P<.001). Table 4 presents the split-half correlation matrix.

Our results indicate that nurses were more hesitant to vaccinate themselves in comparison to respondents in other roles, had higher rates of COVID-19 history, and were more hesitant to vaccinate their children if they had not been vaccinated themselves. These results are important since COVID-19 is still prevalent and predicted to continue for several years. Further, nurses are prominent health care providers with the capacity to influence patients. These findings suggest that public health interventions should target vaccine hesitancy among nurses. This aligns with our previous findings,2,6 and complements studies from other countries of factors influencing nurses’ decisions to vaccinate.8 While not directly comparable, one study of 795 nurses in Greece, conducted in 2022, found 30.9% of respondents were hesitant to receive a booster or new vaccine dosage after initial vaccination,9 a figure that falls into similar ranges around the world.10–12 We believe our project findings relative to hesitancy to vaccinate one’s own child fall within similar ranges of general vaccine hesitancy observed in health care worker populations in these and other studies.

Our report has several limitations. First, it was conducted at a single institution, and captured approximately 15% of potential respondents. It therefore only represents a convenience sample. Additionally, due to a high degree of correlation between potential predictor variables, multivariable analyses were not possible owing to multicollinearity. Furthermore, this project utilized a convenience sample, and was conducted to inform institutional educational efforts. As an attempt to improve the quality of these efforts, generalizability to other populations was not a consideration. Our population was not, and was not intended to be, representative of a wider population of health care workers.

Approximately 232,000 deaths could have been prevented in the United States from May 2021 through September 2022 if all who were eligible for vaccination had kept current.13 Vaccine hesitancy among any segment of the health workforce can be deleterious to efforts within the broader population, and our project signaled significant issues within our nursing population in terms of their own and their children’s vaccination practices. We also detected a heterogeneity in attitudes among HCP that signals a need for tailored communication strategies. For example, tailored communications have been demonstrated to improve vaccination rates among hospital environmental service workers.14 Dedicated efforts toward nurses should be planned in advance of future vaccine introductions.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented as a poster at NAPCRG Annual Meeting in 2022 in Phoenix, Arizona.

Conflicts Disclosure: None of the authors have any conflicts or competing interests to report.

References

- Ruhm CJ. The evolution of excess deaths in the united states during the first two years of the covid-19 pandemic. Am J Epidemiol. Published online May 22, 2023:kwad127. doi:10.1093/aje/kwad127

- Shaw J, Hanley S, Stewart T, et al. Healthcare personnel (HCP) attitudes about coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) vaccination after emergency use authorization. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(1):e814-e821. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab731

- Byrne A, Thompson LA, Filipp SL, Ryan K. COVID-19 vaccine perceptions and hesitancy amongst parents of school-aged children during the pediatric vaccine rollout. Vaccine. 2022;40(46):6680-6687. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.09.090

- Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine receives FDA emergency use authorization for children 6 months through 4 years of age. Pfizer. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-receives-fda-emergency-use

- Reece S, CarlLee S, Scott AJ, et al. Hesitant adopters: COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among diverse vaccinated adults in the United States. Infect Med (Beijing). 2023;2(2):89-95. doi:10.1016/j.imj.2023.03.001

- Shaw J, Stewart T, Anderson KB, et al. Assessment of US healthcare personnel attitudes towards Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in a large university healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(10):1776-1783. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab054

- Indelicato AM, Morley CP, Blatt S, Shaw J, Stewart T. Assessment of healthcare personal attitudes towards vaccinating their children for COVID-19 in a university healthcare system - Survey Instrument. STFM Resource Library. September 12, 2024. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://connect.stfm.org/viewdocument/assessment-of-healthcare-personal-a-1

- Pristov Z, Lobe B, Sočan M. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccination among primary healthcare nurses in the pandemic and post-pandemic period: cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12(6):602. doi:10.3390/vaccines12060602

- Galanis P, Vraka I, Katsiroumpa A, et al. Predictors of second COVID-19 booster dose or new COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among nurses: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(13-14):3943-3953. doi:10.1111/jocn.16576

- McCready JL, Nichol B, Steen M, Unsworth J, Comparcini D, Tomietto M. Understanding the barriers and facilitators of vaccine hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers and healthcare students worldwide: An Umbrella Review. PLoS One. 2023;18(4):e0280439. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280439

- Aldakhlan HA, Khan AS, Alabdulbaqi D. Hesitancy over the COVID-19 vaccine among various healthcare workers: an international narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e53059. doi:10.7759/cureus.53059

- Akbulut S, Boz G, Gökçe A, et al. Evaluation of nurses’ vaccine hesitancy, psychological resilience, and anxiety levels during covid-19 pandemic. Eurasian J Med. 2023;55(2):140-145. doi:10.5152/eurasianjmed.2023.22162

- Jia KM, Hanage WP, Lipsitch M, et al. Estimated preventable COVID-19-associated deaths due to non-vaccination in the United States. Eur J Epidemiol. Published online April 24, 2023:1-4. doi:10.1007/s10654-023-01006-3

- Ortiz C, Shaw J, Murphy S, et al. COVID-19 vaccination among environmental service workers using agents of change. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2022;6:23. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2022.185423

There are no comments for this article.