Background and Objectives: Motivational interviewing (MI) is a patient-centered approach to behavior change counseling that is used among health professionals across multiple disciplines. However, MI training has yet to be broadly offered to health professional (HP) students. This study aimed to evaluate student interest in MI and the efficacy of an MI workshop to assess whether MI training should be incorporated into HP curricula.

Methods: We conducted a needs assessment to evaluate HP student interest in learning MI. We then hosted a 6.5-hour MI workshop, followed by optional standardized patient encounters (SPEs). SPE performance was evaluated with a scored competency assessment.

Results: Needs assessment respondents (N=93) were predominantly medical students (53%), of which 49% were interested in primary care-related fields. Most (58%) reported receiving 0 to 2 hours of MI training in their required curricula, yet 87% intended to use MI and were interested in receiving training. Nineteen students attended the MI workshop. Postworkshop knowledge assessment (N=11) improved by an average of 34% (premean [±SD], 41% [±12]; postmean [±SD], 75% [±10]; P<.001). The SPE mean competency score (5.09) surpassed the threshold for competence of 5.

Conclusions: HP students reported receiving minimal MI training in their curricula despite being highly interested in MI. Interested students responded to our interdisciplinary MI workshop and SPEs with high satisfaction, suggesting that HP schools may benefit from incorporating MI into their curricula. Nevertheless, response rates were low, and selection bias may have skewed responses toward more favorable perceptions of MI.

The leading causes of death in the United States are predominantly chronic illnesses driven by modifiable behavioral risk factors.1,2 Consequently, up to 75% of primary care visits include mental or behavioral health components;3 however, physicians report low confidence in helping patients invoke behavior change and cite lack of specific training as a barrier to doing so.4,5 Integrated primary care models where multidisciplinary teams collaborate to support behavior change are growing;6 therefore, equipping health care providers in multiple disciplines with skills to deliver effective health behavior counseling is necessary.

One behavior counseling tool is motivational interviewing (MI),7 which uses a collaborative, autonomy-supportive approach to increase motivation for behavior change.8,9 MI positively influences health outcomes,10,11 and a wide variety of health care professionals and trainees are learning MI.12–24 However, few studies have inquired about the student perspective, including interest in and familiarity with MI, across health professional (HP) students of multiple fields and specialties of interest. Eliciting student interest in MI is an important first step in determining whether MI training should be included in HP students’ core curricula. Therefore, this study aimed to (a) assess HP student perspectives on MI education, and (b) deliver and assess a multidisciplinary MI training for interested students.

Needs Assessment

We conducted an anonymous needs assessment survey to assess experience with and interest in MI among HP students at a large, public, Midwestern university. The survey was distributed via the university’s Interprofessional Education Center. We analyzed the survey data in Stata (StataCorp) using descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis. Due to the small sample size, we used Fisher’s exact test (P<.05) and excluded missing observations from analysis. All surveys received Institutional Review Board exemption.

MI Workshop and Evaluation

The MI workshop was originally designed by one author (K.R.) using the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) guidelines25 and was refined over 35 years of experience training over 1,000 health care providers. The workshop, which lasted 6.5 hours, was shortened from typical introductory MINT trainings to increase the feasibility of student attendance. The workshop consisted of lectures, live demonstrations, and practice among peers. Three additional MI experts from the fields of medicine, nutrition, and public health provided feedback to students during practice activities. We distributed pre- and postworkshop surveys to workshop attendees, which included a quiz along with additional user satisfaction questions on the postworkshop survey. We analyzed results in Stata using paired t tests (Fisher’s exact P<.05 significance).

Standardized Patient Encounter and Evaluation

Optional standardized patient encounters (SPEs) occurred 1 to 3 weeks after the workshop. The SPEs consisted of a 30-minute review of MI concepts, followed by a 30-minute scenario on smoking cessation, where students used MI with an MI-trained standardized patient (SP). SPs evaluated student performance with the OnePass tool, a 7-point scale, where 5 is the passing score for competence.26 We gathered feedback on the SPEs via an anonymous survey that was analyzed in Qualtrics (Qualtrics LLC). All surveys and supplemental material, including the SPE scenario and grading rubric, are available on the STFM Resource Library.27

Funding

Funding for this study was obtained from a capstone grant for medical students. Funding supported high-quality MI training by an experienced MI instructor (author KR) and several facilitators.

Needs Assessment

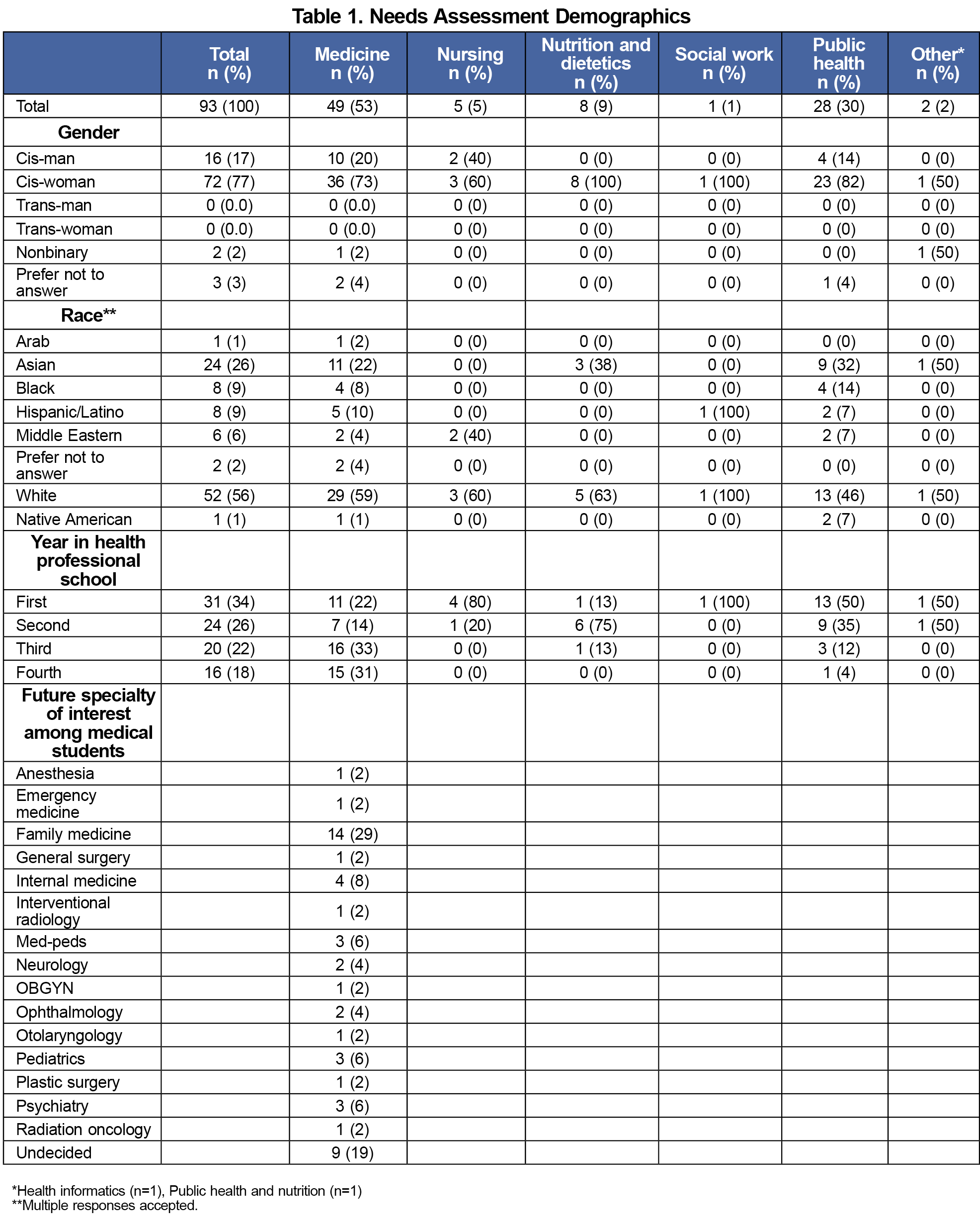

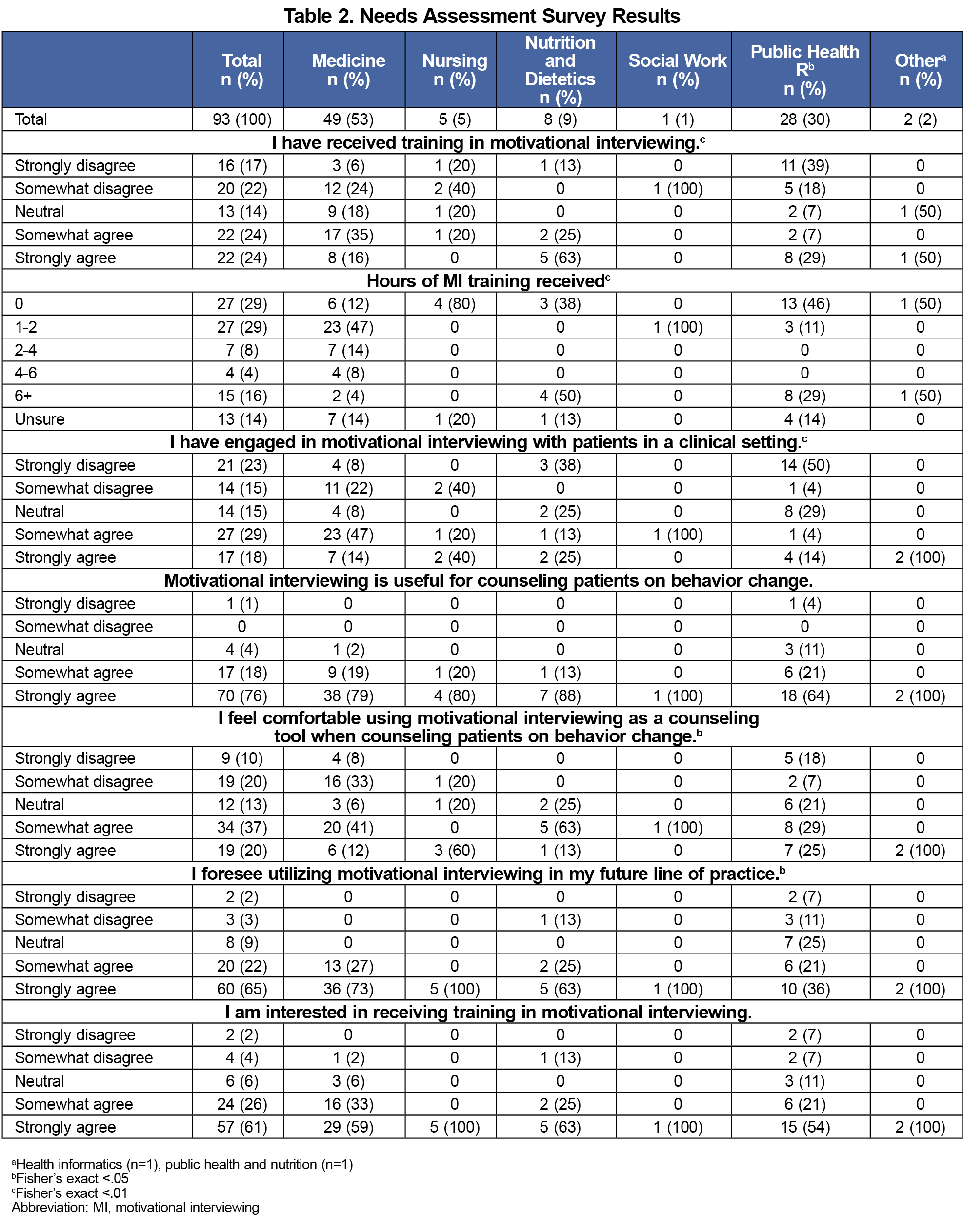

Respondents (N=93) predominantly represented medicine (53%) and public health (30%) programs (Table 1). Among medical students, 49% were interested in primary care-related fields (family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, med-peds).

A majority of respondents (58%) reported receiving 0 to 2 hours of MI training in their required curricula. A majority felt that MI is useful for counseling patients on behavior change (94%), intended to use MI in future practice (87%), and were interested in receiving MI training (87%; Table 2). Nutrition students were more likely to have received MI training and had the highest reported hours of prior MI training, while social work and medical students reported greater use and comfort with MI in clinical settings (P<.05).

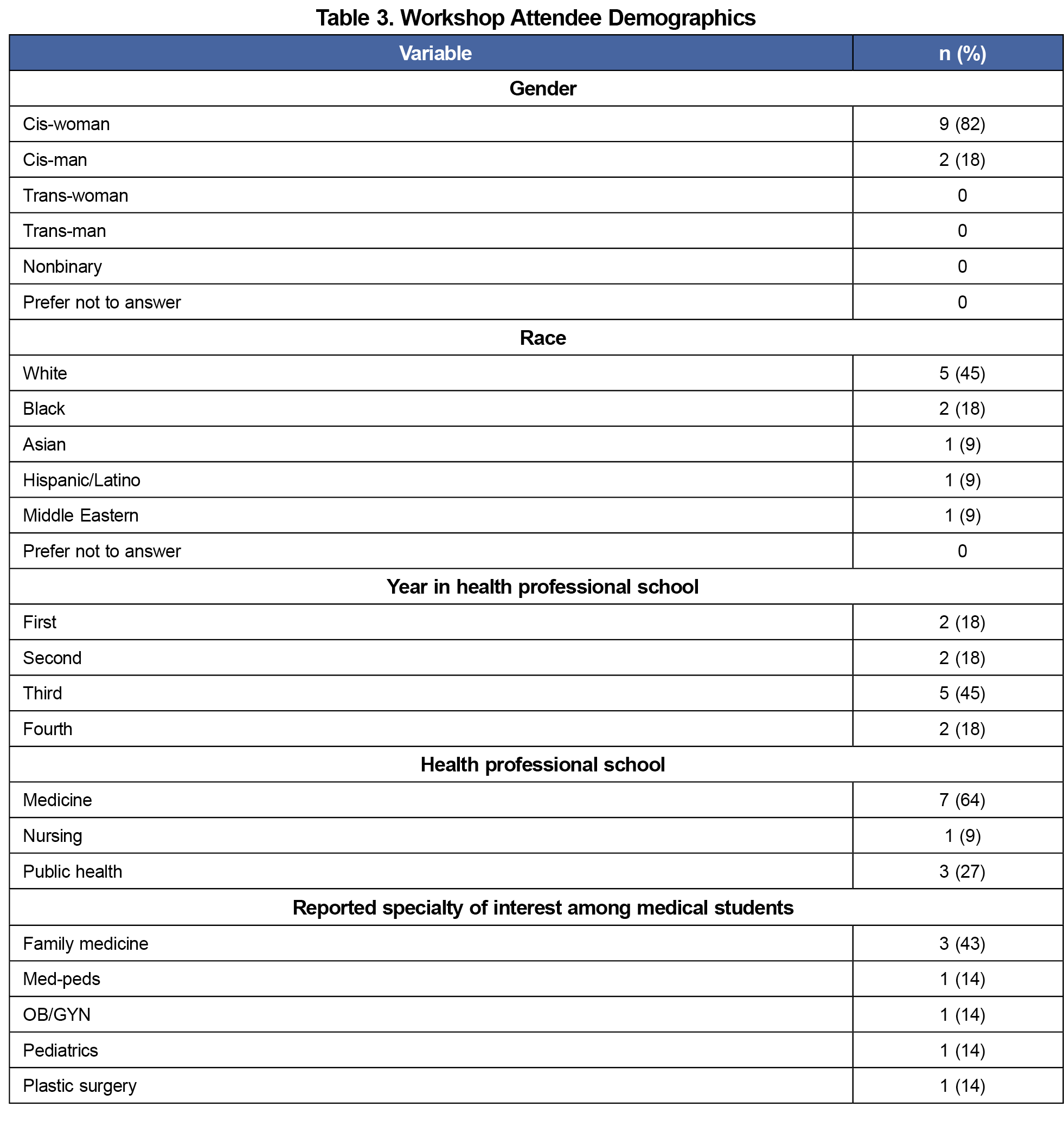

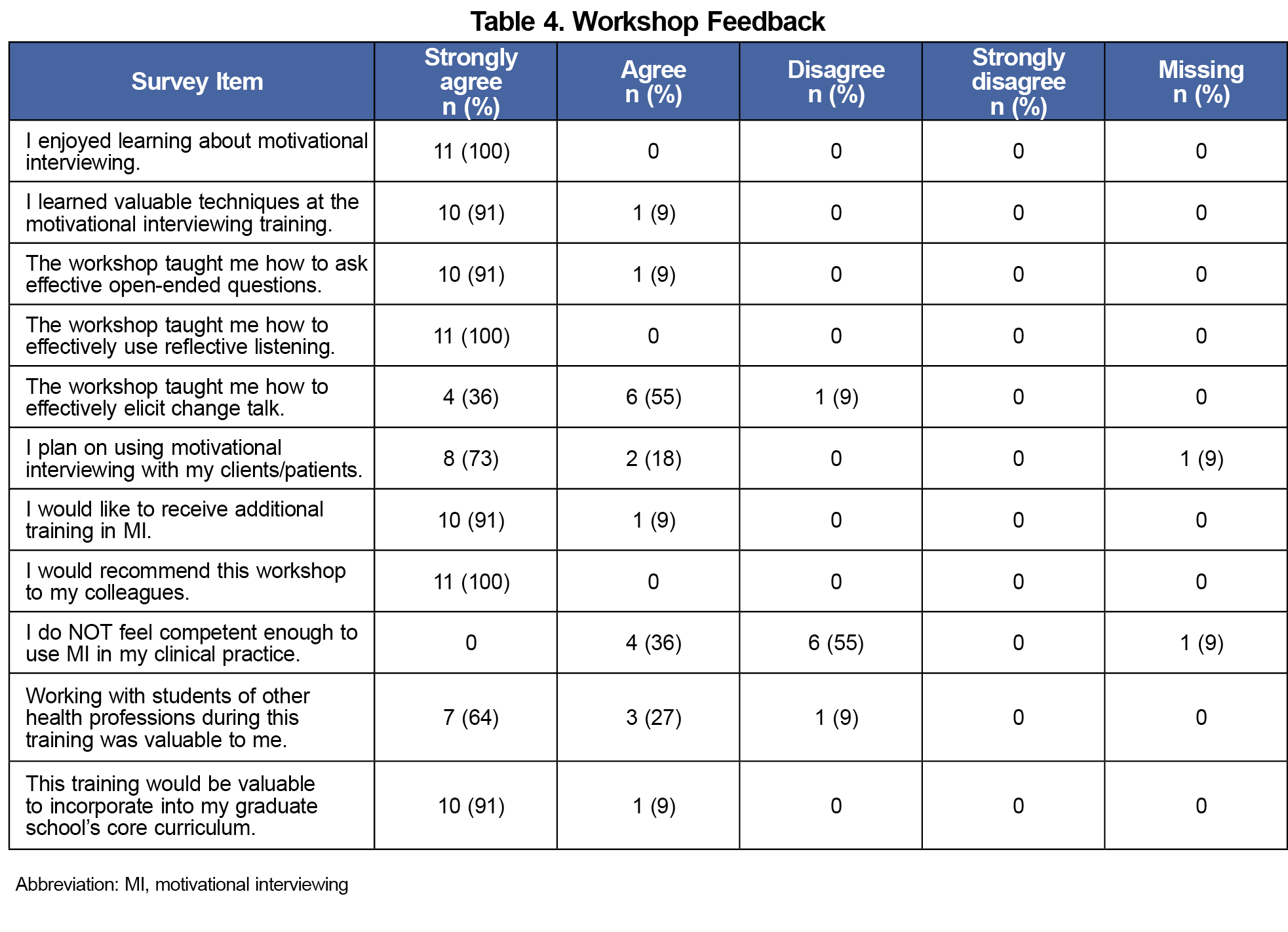

MI Workshop

Of the 19 workshop attendees, 11 completed both pre- and postsurveys and were included in analyses. Attendees were predominantly medical students (64%) and in their third year of school (45%; Table 3). Among medical students, 71% were interested in primary care-related fields (family medicine, pediatrics, med-peds). Postworkshop quiz scores significantly improved by an average of 34% (premean [±SD], 41% [±12]; postmean [±SD], 75% [±10]; P<.001). All attendees felt as though the workshop taught them valuable techniques and wanted additional training (100%). Most felt that working with students of other professions was valuable to their learning (91%). All felt that the workshop should be added to their HP school’s core curriculum (100%; Table 4).

Standardized Patient Encounter

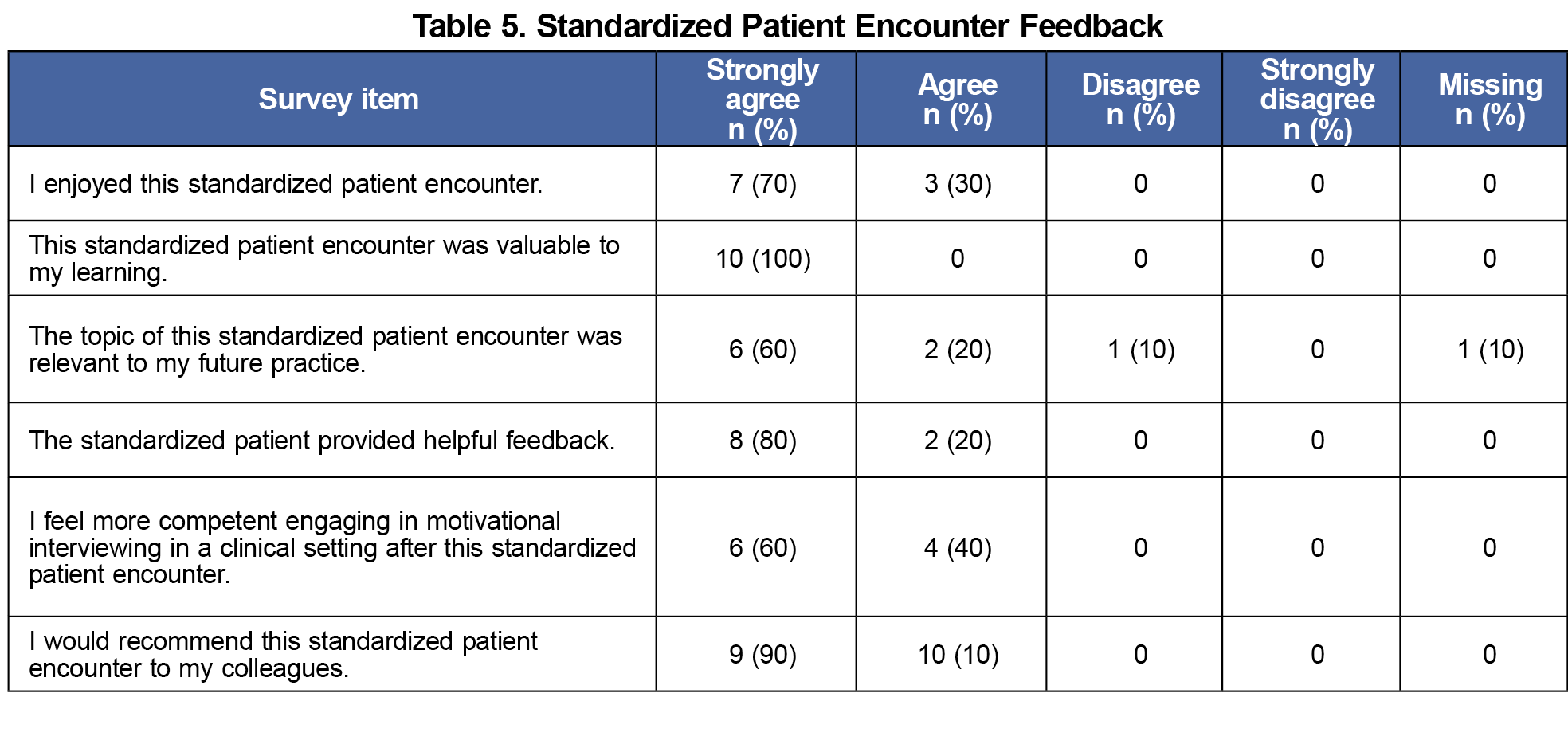

Ten students completed the SPEs (50% medical students). The mean OnePass score for all participants was 5.09. All participants reported gaining valuable feedback from the SP and felt more competent engaging in MI in a clinical setting afterward (Table 5).

This study, which characterized MI exposure and interest among students across several HP schools, revealed minimal MI training exposure despite intent to use MI and interest in receiving training. As an introduction to MI principles, this 6.5-hour MI workshop resulted in increased knowledge of MI concepts and competence in the SPEs. SPE participation also increased confidence in MI use, which may increase the likelihood of future clinical application. Future research should evaluate the impact of early MI training on long-term use of MI and patient care outcomes, particularly because workshop attendees desired more MI training and may therefore seek out additional learning opportunities throughout their careers.

Not only did this study elucidate strong interest in learning and using MI among students, which may have important health benefits for future patients, but also the results may contribute to understanding how HP schools can help curb the growing primary care physician shortage.28 Interprofessional collaboration and health behavior change counseling are both essential for effective provision of primary care. Feeling better prepared to care for patients in primary care settings, both from having relevant counseling skills and from collaborating with colleagues interprofessionally, may be an important part of ensuring student interest in primary care, thus providing additional basis for HP schools to incorporate interprofessional MI training into their curricula.

HP schools have thus far adopted MI to different extents. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics has more substantially incorporated MI into its educational curricula, possibly explaining why the nutrition students in the needs assessment reported more prior training. Therefore, implementing interprofessional MI training across HP schools may be beneficial to gain insights from prior MI-related curricular changes.

Nevertheless, although the needs assessment elicited input from students of various HP schools, response rates in our study were overall low and did not adequately represent certain HP schools (eg, social work). Additionally, due to selection bias, responses were likely skewed toward more favorable perceptions of MI and greater interest in training. Though workshop attendees unanimously agreed that the workshop should be incorporated into required curricula, the sample was small, and underrepresented students may not agree. Regardless, this study revealed student interest in learning MI across HP schools and offered an effective model for interdisciplinary MI training that is free of charge for students. HP schools, therefore, should collaborate to offer interprofessional MI training for their students.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kendrin Sonneville, Marsha Benz, Terry Bravender, Shannon Considine, and Emerson Delacroix for their contributions to the motivational interviewing workshop as facilitators and standardized patients.

Financial Support: Funding was obtained from a Capstone for Impact Grant available for medical students at The University of Michigan Medical School.

Presentations:

- Family Medicine Midwest Conference, September 30, 2023, Naperville, IL.

- Lifestyle Medicine Conference, October 31, 2023, Orlando, FL.

Conflict of Interest Statement: Author Kenneth Resnicow was compensated as the lead instructor for the motivational interviewing workshop offered in this initiative.

References

- Xu J, Murphy, SL, Kochanek, KD, Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS data brief no. 456. 2022(456):1-8. doi:10.15620/cdc:122516

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1,238-1,245. doi:10.1001/jama.291.10.1238

- Robinson PJ, Reiter JT. Behavioral Consultation and Primary Care: A Guide to Integrating Sevices. Springer; 2007. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-0-387-32973-4

- Wechsler H, Levine S, Idelson RK, Schor EL, Coakley E. The physician’s role in health promotion revisited—a survey of primary care practitioners. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(15):996-998. doi:10.1056/NEJM199604113341519

- Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24(6):546-552. doi:10.1006/pmed.1995.1087

- Reiter JT, Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL. The Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model: an overview and operational definition. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25(2):109-126. doi:10.1007/s10880-017-9531-x

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. Guilford Press; 1991. doi:10.1002/casp.2450020410

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change.Guilford Press; 2012.

- Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. Understanding motivational interviewing. Accessed July 14, 2023.https://motivationalinterviewing.org/understanding-motivational-interviewing

- Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305-312.

- Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Coffman CJ, et al. Physician communication techniques and weight loss in adults: project CHAT. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):321-328. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.06.005

- Boykan R, Gorzkowski J, Marbin J, Winickoff J. Motivational interviewing: a high-yield interactive session for medical trainees and professionals to help tobacco users quit. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10831. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10831

- Tobey M, Marcovitz D, Aragam G. A 1-hour session to refresh motivational interviewing skills for internal medicine residents using peer interviews. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10679. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10679

- Azari S, Ratanawongsa N, Hettema J, et al. A skills-based curriculum for teaching motivational interviewing-enhanced screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) to medical residents. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10080. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10080

- Matsumoto AN, DeSena D, Kuzma EK, et al. The evolution of an interprofessional education motivational interviewing workshop: finding the right balance. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2020;20:100342. doi:10.1016/j.xjep.2020.100342

- Jacobs NN, Calvo L, Dieringer A, Hall A, Danko R. Motivational interviewing training: a case-based curriculum for preclinical medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11104. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11104

- Brogan Hartlieb K, Engle B, Obeso V, Pedoussaut MA, Merlo LJ, Brown DR. Advanced patient-centered communication for health behavior change: motivational interviewing workshops for medical learners. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10455. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10455

- Fortune J, Breckon J, Norris M, Eva G, Frater T. Motivational interviewing training for physiotherapy and occupational therapy students: effect on confidence, knowledge and skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(4):694-700. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2018.11.014

- Widder R. Learning to use motivational interviewing effectively: modules. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2017;48(7):312-319. doi:10.3928/00220124-20170616-08

- Spector A, Ash E, Garland B, et al. Perceptions of motivational interviewing in genetic counseling practice and training. J Genet Couns. 2022;31(5):1,173-1,182. doi:10.1002/jgc4.1588

- Kaczmarek T, Kavanagh DJ, Lazzarini PA, Warnock J, Van Netten JJ. Training diabetes healthcare practitioners in motivational interviewing: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2022;16(3):430-449. doi:10.1080/17437199.2021.1926308

- Bray KK, Bennett K, Catley D. Fidelity of motivational interviewing training for dental hygiene students. J Dent Educ. 2021;85(3):287-292. doi:10.1002/jdd.12448

- Brandford A, Adegboyega A, Combs B, Hatcher J. Training community health workers in motivational interviewing to promote cancer screening. Health Promot Pract. 2019;20(2):239-250. doi:10.1177/1524839918761384

- Kaczmarek T, Van Netten JJ, Lazzarini PA, Kavanagh D. Effects of training podiatrists to use imagery-based motivational interviewing when treating people with diabetes-related foot disease: a mixed-methods pilot study. J Foot Ankle Res. 2021;14(1):12. doi:10.1186/s13047-021-00451-1

- Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. Motivational Interviewing: Resources for Trainers. Updated July 2020. Accessed May 4, 2024.https://motivationalinterviewing.org/training-new-mi-trainers-manual-2020

- McMaster F, Resnicow K. Validation of the one pass measure for motivational interviewing competence. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(4):499-505. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.12.014

- Lajaunie A, Vela N, Kimmel-Supron H, Small S, Resnicow K, Polling PE. Motivational interviewing workshop. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Resource Library. 2024. Accessed January 29, 2024.https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/motivational-interviewing-workshop?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

- Reynolds R, Chakrabarti R, Chylak D, Jones K, Iacobucci W, Dall T. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2019 to 2034. ResearchGate. June 2021. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.29404.92808h

There are no comments for this article.