Family medicine (FM) clerkships require students to achieve a broad set of objectives including clinical knowledge, verbal and written communication, physical examination, and analytic skills. These objectives can be difficult to measure with a solitary assessment. Therefore, many FM clerkships employ a combination of assessment strategies to evaluate medical students’ objective achievement.1 However, few clerkships have formally evaluated the quality, relevance, and validity of the multiple assessments that determine the final grade to ensure they accurately depict students’ performance.1-3 We developed a conceptual framework to assess the theoretical and empirical relationship between the different assessment tools used in our clerkship.4,5 Here we present the results of the correlation analyses between multiple assessments to determine the relevance and validity of each assessment component and highlight recommended changes.1-3

RESEARCH BRIEF

Evaluating Student Clerkship Performance Using Multiple Assessment Components

Oladimeji Oki, MD | Zoon Naqvi, MBBS, EdM, MHPE | William Jordan, MD, MPH | Conair Guilliames, MD | Heather Archer-Dyer, MPH, CHES | Maria Teresa Santos, MD

PRiMER. 2024;8:25.

Published: 4/24/2024 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2024.160111

Introduction: Family medicine clerkships utilize a broad set of objectives. The scope of these objectives cannot be measured by one assessment alone. Using multiple assessments aimed at measuring different objectives may provide more holistic evaluation of students. A further concern is to ensure longitudinal accuracy of assessments. In this study, we sought to better understand the relevance and validity of different assessment tools used in family medicine clerkships.

Methods: We retrospectively correlated family medicine clerkship students’ scores across different assessments to evaluate the strengths of the correlations, between the different assessment tools. We defined ρ<0.3 as weak, ρ>0.3 to ρ<0.5 as moderate, and ρ>0.5 as high correlation.

Results: We compared individual assessment scores for 267 students for analysis. The correlation of the clinical evaluation was 0.165 (P<.01); with case-based short-answer questions it was 0.153 (P<.01); and with objective structured clinical examinations it was -0.246 (P<0.01).

Conclusion: Overall low levels of correlations between our assessments are expected, as they are each designed to measure different objectives. The relatively higher correlation between component scores supports convergent validity while correlations closer to zero suggest discriminant validity. Unexpectedly, comparing the multiple-choice questions and objective, structured clinical encounter (OSCE) assessments, we found higher correlation, although we believe these should measure disparate objectives. We replaced our in-house multiple-choice questions with a nationally-standardized exam and preliminary analysis shows the expected weaker correlation with the OSCE assessment, suggesting periodic correlations between assessments may be useful.

Conceptual Framework

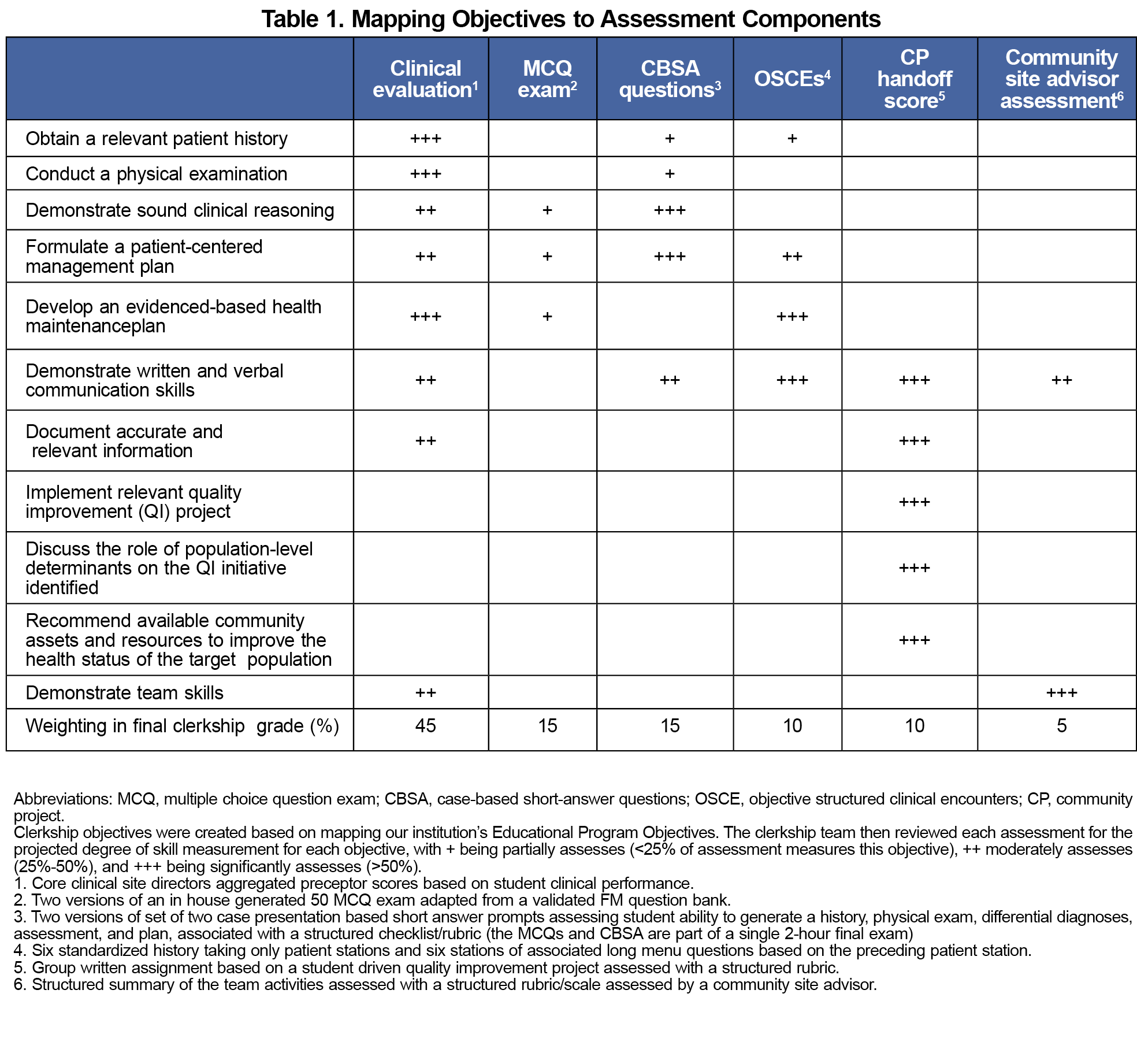

The FM clerkship has historically used multiple components to evaluate student performance. Table 1 demonstrates how we developed a framework to map the relationship between the assessment tools and clerkship objectives.4,5 When writing clerkship objectives, the clerkship team aimed to keep the objectives clear, concise, measurable, and closely aligned to the specific goals and learning outcomes of our institution’s overall educational program objectives. The framework was developed, reviewed, and refined through data analysis of scores and educational literature over several years by multiple members of the clerkship team.4, 5 The final grade in the required FM clerkship includes the following components:

- Clinical evaluation (CE),

- Multiple-choice exam (MCQs),

- Case-based short-answer questions (CBSA),

- Objective structured clinical encounters (OSCEs), and

- A community project (CP) handoff and advisor score.

These scores evaluate students’ performance in clinical knowledge, procedural and documentation skills, clinical reasoning, interpersonal skills, teamwork, and implicit and explicit attitudes. None of our assessment tools alone can assess the achievement of all objectives.6 Table 1 maps our assessments to the degree of expected measurement of our objectives.

Validity and Reliability Measures

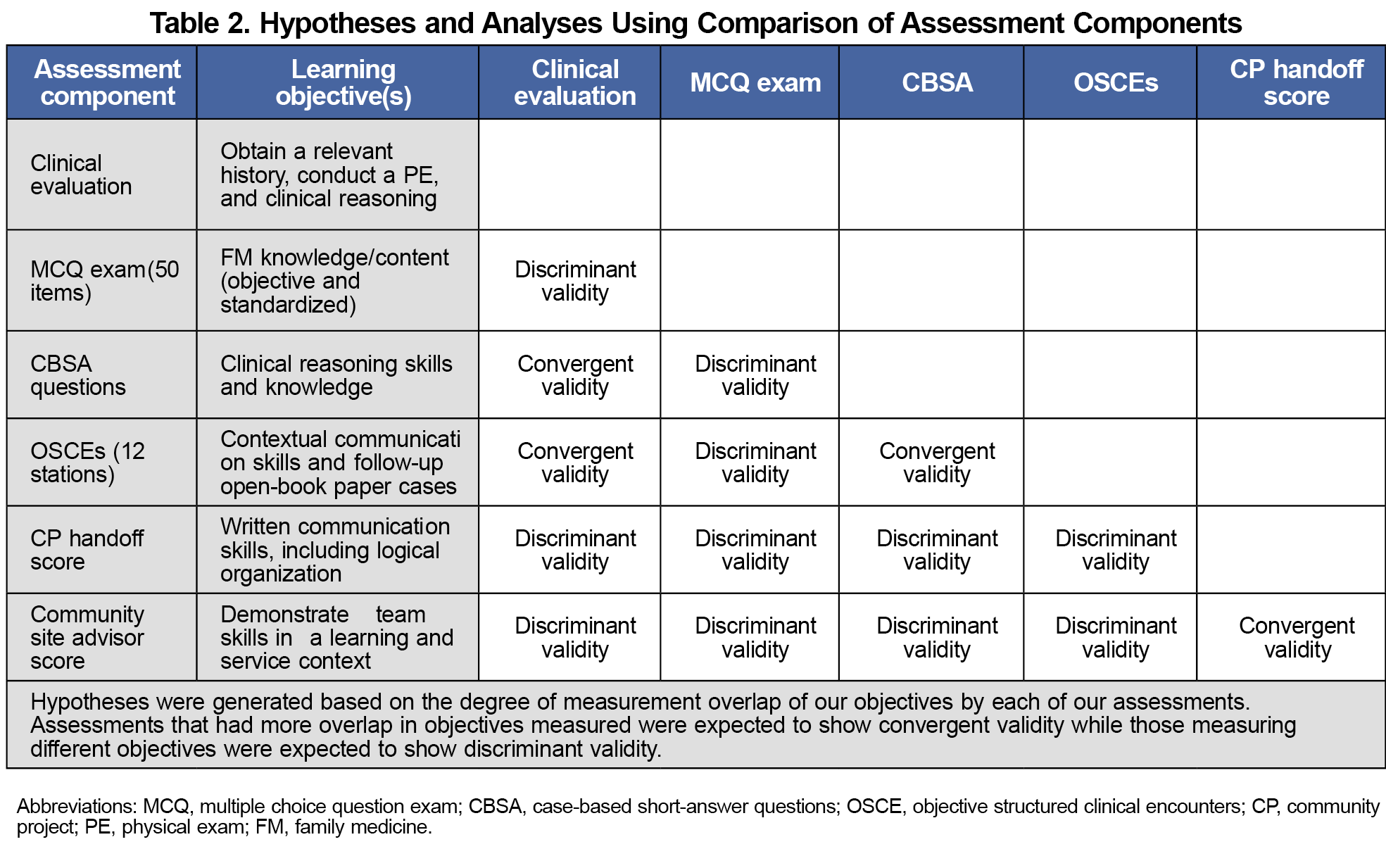

Constructing multiple, validity-related hypotheses to assess whether comparative assessment tool scores reflect certain abilities is not always straightforward.2,7-13 We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient (ρ) to study the relationship between the different tools (scale: 1 to -1), allowing a measure of the similarity of multiple assessment scores.2,10,12 For this review, we determined that ρ<0.3 represented weak correlation, ρ>0.3 to ρ<0.5 moderate correlation, and ρ>0.5 represented high correlation.13 While weaker levels of correlation overall are expected, as no two assessments are intended to measure the same objectives, we also expect tools that have significant overlap in intended assessed objectives (eg, OSCEs and CBSA), to show relatively higher levels of correlation suggesting convergent validity (CV, here defined as ρ>0.2). Likewise, those tools measuring disparate objectives, such as the CE and the CP, will support discriminant validity (DV), or ρ closer to 0. Table 2 reflects our group’s hypotheses on how different tools relate to each other in terms of validity, based on the intended measured objectives.

Study Design

We performed a retrospective correlation analysis of a pre-existing database containing medical students’ scores for component assessments during their FM rotations. We compared all students from 2 academic years (2018-2020) with the same preclinical training. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, OSCEs were discontinued, and CE scores were modified to pass/fail for the last 3 of the 12 rotations for 2019-2020. Therefore, for balance, we included all students from the first 9 rotations of the 2 academic years in the analysis. Albert Einstein College of Medicine deemed our study exempt from approval (IRB #: 2019-10288).

The required 4-week FM clerkship takes place in the third year of medical school training. The final grade (honors, high pass, pass, low pass, or fail) is determined using criterion-based cutoffs of the aggregate scores.

Data Analysis

We entered assessment scores into a correlation matrix representing correlation for the combined 2 years using SPSS 24.0 software. We then compared the correlation analysis to the hypothesized level of correlation (convergent vs divergent validity) based on the predefined intended assessment measurement of objectives.

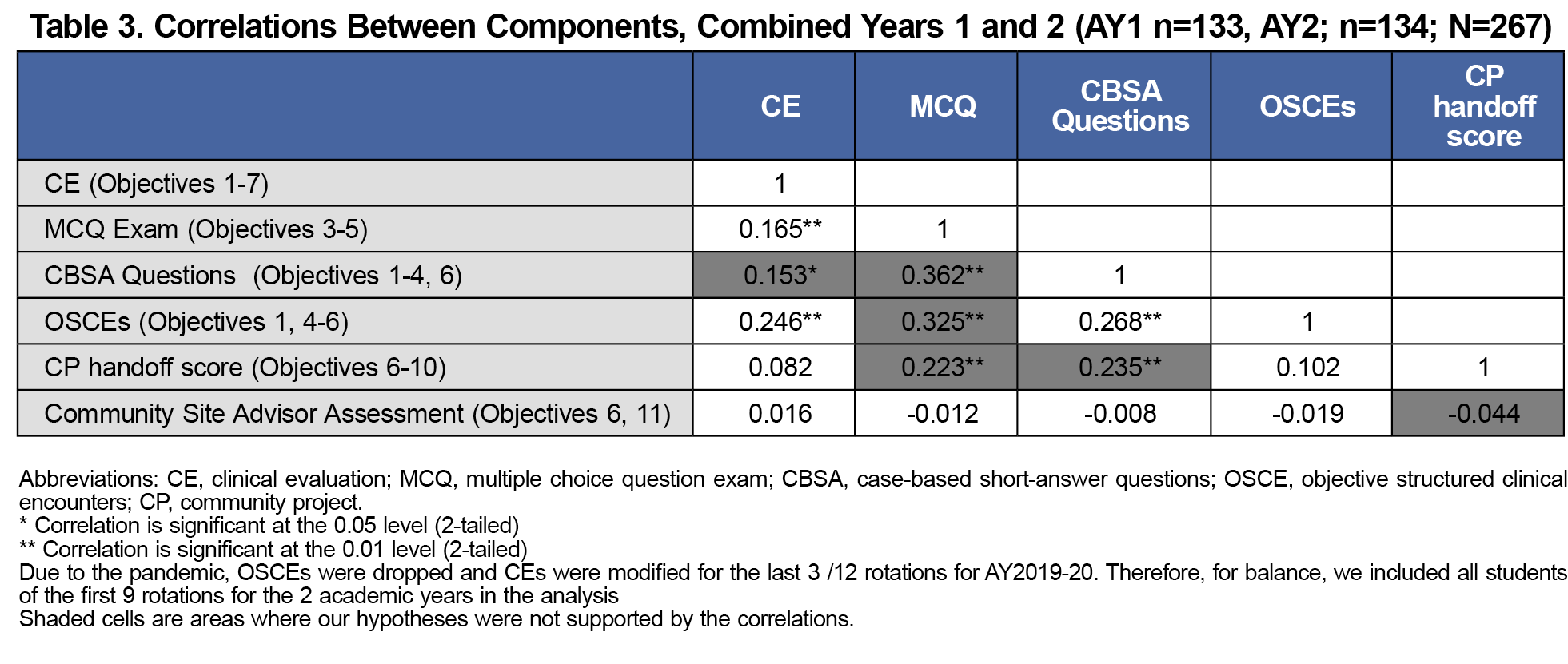

Table 3 shows a detailed correlation matrix using all components of the evaluation to examine correlation between components. We included data for 267 students in 2 academic years (2018-2019 and 2019-2020). Table 3 also shows the correlations between the component scores. All correlations were overall weak to moderate, varying from a maximum of 0.36 to -0.044.

The overall weak-to-moderate correlations among our assessment tools were expected and support the use of multiple assessments in measuring student performance during the FM clerkship. Having multiple assessments allows us to evaluate achievement of multiple, disparate clerkship objectives leading to a more holistic assessment of student performance. Our a priori assumption was that the correlation between components that assess more overlapping objectives (eg, OSCEs and CBSA) would support CV. Interestingly, some results did not support our assumptions. For example, the correlation of the MCQ scores (intended to measure clinical recall and limited clinical reasoning) with OSCEs (measuring communication), although moderate, are among the strongest correlations in our data (ρ= 0.325, Table 3) and does not support the expected DV.6 This suggests that these components may be assessing unintended objectives. For example, our MCQs may be assessing verbal/reading objectives as well, or our OSCEs may be measuring more clinical recall/reasoning than intended. Our MCQs did not meet the expected hypothesis with our CBSA nor our CP handoff score. As expected, the correlations of the CP and the community advisor scores with the other scores were closer to 0, suggesting stronger DV.

Limitations

Individual bias is a potential confounder in measuring assessed objectives, and this paper does not explicitly address such bias. Regardless of how thorough a grading rubric is, individual graders may still to interpret the rubric differently. For example, clinical evaluation by preceptors has historically been difficult to standardize and offers ample opportunity for bias/unintended objective evaluation. This type of evaluation needs further standardization by developing a more user-friendly rubric, and continued faculty development to minimize the potential for nonmeasured objectives to be included in the assessment.

A second confounder is the unequal weighting of assessments. This inequality could potentially influence students to put more effort into more highly weighted assessments over others, introducing further variables into our correlation scores. As our weighting system was designed so that students needed to do well in all components to achieve honors for the clerkship, we do not believe this is a significant confounder. However, assessment weighting is a topic that should be studied further.

Evaluating assessments in a comparative format allowed us to identify gaps in the validity of our assessments. As our assessments were created to measure student knowledge, skills, and behaviors in relation to our course objectives, we aim for them to accurately assess said objectives. We use multiple assessments to measure a disparate set of objectives that cannot be measured with one assessment alone. Ideally, assessment scores should have weak correlation with one another; otherwise the multiple assessments may be unnecessary and redundant. Correlating assessment scores allowed our clerkship team to better understand the validity of our assessments by noting if the assessments are measuring the intended objectives. Based on our results, we replaced our in-house MCQs with a nationally standardized exam to assess clinical knowledge more reliably. Preliminary analysis indicates weaker correlation of our new MCQs with OSCEs and CE, a scenario better aligned to what we initially hypothesized. Regularly assessing clerkship-grading components in this manner provides an opportunity to contribute to validation of the measures and ensure they are properly assessing the course objectives.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: Data from this article were presented at the STFM conference on Medical Student Education in Austin, Texas on February 3, 2018, as well as at the Family Medicine Education Consortium conference in Rye, New York on November 10, 2018.

References

- Shumway JM, Harden RM; Association for Medical Education in Europe. AMEE Guide No. 25: the assessment of learning outcomes for the competent and reflective physician. Med Teach. 2003;25(6):569-584. doi:10.1080/0142159032000151907

- Downing SM. Validity: on meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Med Educ. 2003;37(9):830-837. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01594.x

- Beckman TJ, Cook DA, Mandrekar JN. What is the validity evidence for assessments of clinical teaching? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1159-1164. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0258.x

- Lee M, Wimmers PF. Clinical competence understood through the construct validity of three clerkship assessments. Med Educ. 2011;45(8):849-857. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03995.x

- McLaughlin K, Vitale G, Coderre S, Violato C, Wright B. Clerkship evaluation--what are we measuring? Med Teach. 2009;31(2):e36-e39. doi:10.1080/01421590802334309

- Sam AH, Hameed S, Harris J, Meeran K. Validity of very short answer versus single best answer questions for undergraduate assessment. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):266. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0793-z

- Arora C, Sinha B, Malhotra A, Ranjan P. Development and Validation of Health Education Tools and Evaluation Questionnaires for Improving Patient Care in Lifestyle Related Diseases. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(5):JE06-JE09. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2017/28197.9946

- Badyal DK, Singh S, Singh T. Construct validity and predictive utility of internal assessment in undergraduate medical education. Natl Med J India. 2017;30(3):151-154.

- Marceau M, Gallagher F, Young M, St-Onge C. Validity as a social imperative for assessment in health professions education: a concept analysis. Med Educ. 2018;52(6):641-653. doi:10.1111/medu.13574

- Royal KD. Four tenets of modern validity theory for medical education assessment and evaluation. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:567-570. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S139492

- Sennekamp M, Gilbert K, Gerlach FM, Guethlin C. Development and validation of the “FrOCK”: frankfurt observer communication checklist. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2012;106(8):595-601. doi:10.1016/j.zefq.2012.07.018

- Young M, St-Onge C, Xiao J, Vachon Lachiver E, Torabi N. Characterizing the literature on validity and assessment in medical education: a bibliometric study. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(3):182-191. doi:10.1007/S40037-018-0433-X

- Abma IL, Rovers M, van der Wees PJ. Appraising convergent validity of patient-reported outcome measures in systematic reviews: constructing hypotheses and interpreting outcomes. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):226. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2034-2

Lead Author

Oladimeji Oki, MD

Affiliations: Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Co-Authors

Zoon Naqvi, MBBS, EdM, MHPE - Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

William Jordan, MD, MPH - New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene, New York, NY

Conair Guilliames, MD - Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Heather Archer-Dyer, MPH, CHES - Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Maria Teresa Santos, MD - Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Corresponding Author

Oladimeji Oki, MD

Correspondence: Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Email: ooki@montefiore.org

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.