Introduction: US child firearm fatality rates have risen since 2013. Child Access Prevention (CAP) laws aimed at reducing minors’ access to firearms have existed since the 1980s. However, specific requirements for safe storage of firearms, standards of negligence, and penalties for offenders vary significantly by state, yielding a heterogeneous body of CAP legislation. A few studies have investigated the relative impacts of these laws on child firearm injury rates, with sometimes conflicting results. Here, we present a rapid review of the existing literature on CAP laws and their apparent impact on firearm-related injuries among US children, to assess whether CAP laws are an effective tool for reducing child firearm injuries.

Methods: We conducted a rapid review of published reports that evaluated the impact of CAP laws on pediatric firearm injuries and/or deaths in the United States. We extracted target population data and outcomes of each study. The data are presented narratively.

Results: A total of 14 articles met criteria for evaluation. Taken together, these studies showed that implementation of CAP legislation was associated with reduced pediatric firearm injuries and fatalities. Moreover, longitudinal or time-series studies that examined changes in pediatric firearm injuries pre/post-CAP legislation yielded the most consistent and robust findings.

Conclusion: CAP laws were found to be associated with reduced pediatric firearm injuries and deaths, with the magnitude of effect being proportional to CAP law stringency.

Pediatric firearm injuries and fatalities have increased in the United States since 2013. In 2020, 4,368 children aged 19 and younger died of firearm-related injuries, the highest number in the previous 15 years and a 29% increase from 2019.1 Roughly one-third of US households with children have firearms. Of those households, approximately 30% report storing all firearms unloaded and locked, while 20% report storing at least one firearm loaded and unlocked.2 Greater firearm availability contributes to increased child deaths from firearm-related suicide, homicide, and unintentional injury.3 Firearm injuries are now the leading cause of death in US youth aged 0-24 years.1,4 This growing burden of US firearm deaths is an urgent public health crisis.

Since the 1980s, some states have sought to reduce child firearm access by regulating firearm storage practices and imposing liability on adults who enable unlawful access. Such child access prevention (CAP) laws have been enacted in 24 states and vary considerably in their terms.5 The most stringent CAP laws, referred to as “child could access” or “safe storage” laws, typically require safe firearm storage with felony penalties for violations. Less stringent CAP laws, referred to as “reckless provision” laws, only impose liability for directly providing firearms to minors, or when a minor accesses firearms to cause bodily injury or death.5

While some studies have shown associations between CAP legislation and reduced pediatric firearm mortality, the terms and reported efficacy of CAP laws vary considerably by state. Given recent and ongoing increases in pediatric firearm mortality, there is pressing need to determine whether and which CAP strategies are effective. Therefore, we conducted a rapid review of existing literature that examined the impact of CAP legislation on US pediatric firearm injuries and deaths. We hypothesized that studies with a longitudinal or temporal element (ie, those which compared pediatric firearm injury rates before and after CAP laws were adopted) would yield the most consistent results.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

This rapid review synthesizes the impact of CAP laws on pediatric firearm mortality in the United States. We conducted a PubMed literature search in January 2023 (with periodic updates until submission), using the search terms “CAP laws,” “firearm,” and “mortality.” All available publication years were considered for inclusion. The Boolean NOT terms “opioid” and “Medicaid” excluded literature beyond the scope of this review. Two independent reviewers performed a rapid, functional review of titles and abstracts to confirm relevance of the results. The search was limited to studies and reviews that examined US CAP laws written in English. Included studies met the following additional criteria:

- Related to CAP laws or policy change;

- Evaluation of statistics related to firearm-related injury and/or mortality in the pediatric and young adult populations (aged 0-24 years) within or across CAP law states; and

- Peer reviewed publication in a relevant medical journal.

For each article we extracted location, population demographics, time frame, and summary outcomes data related to the impact of CAP legislation on pediatric firearm injuries and mortality, presented tabularly and narratively herein.

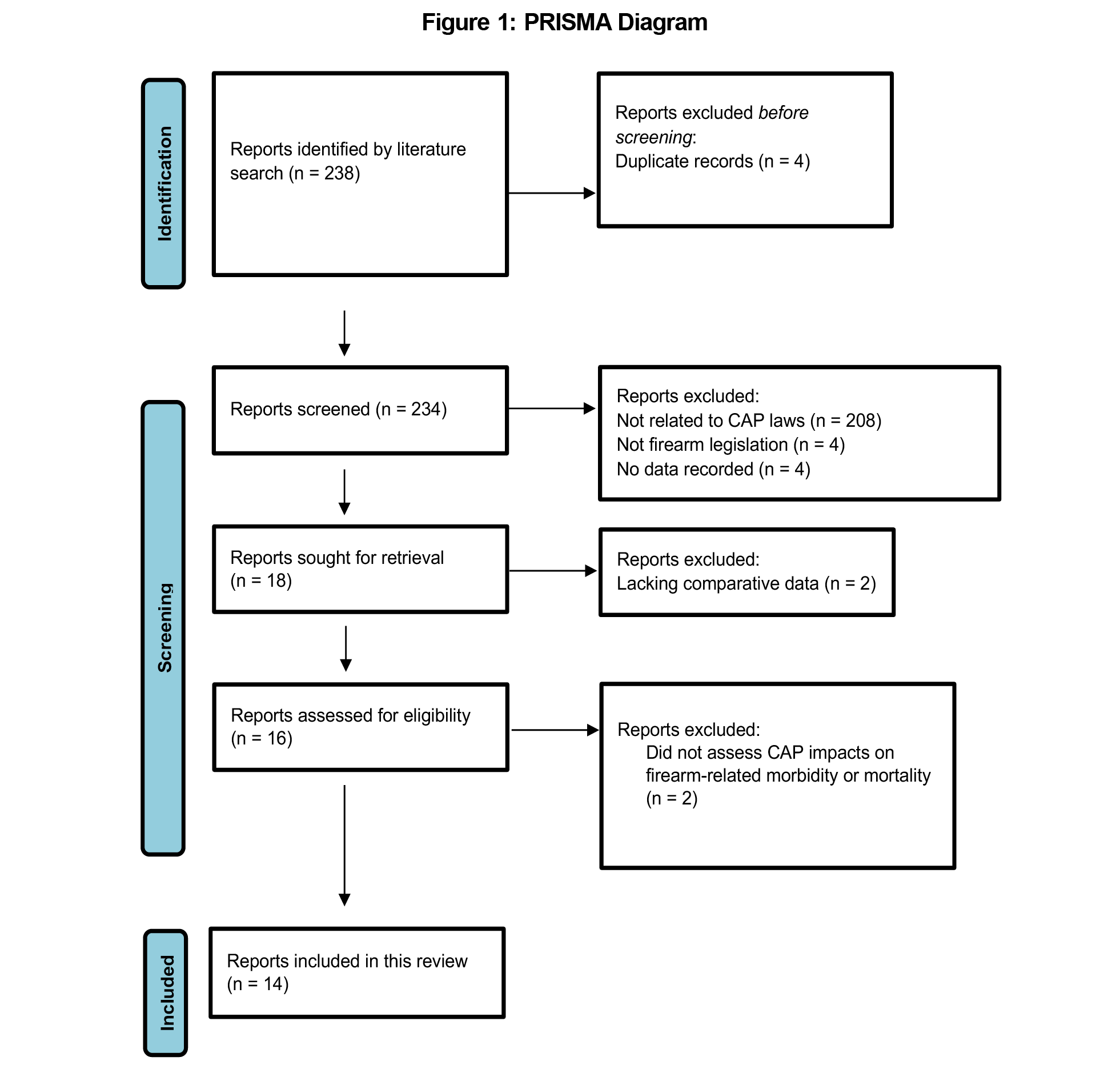

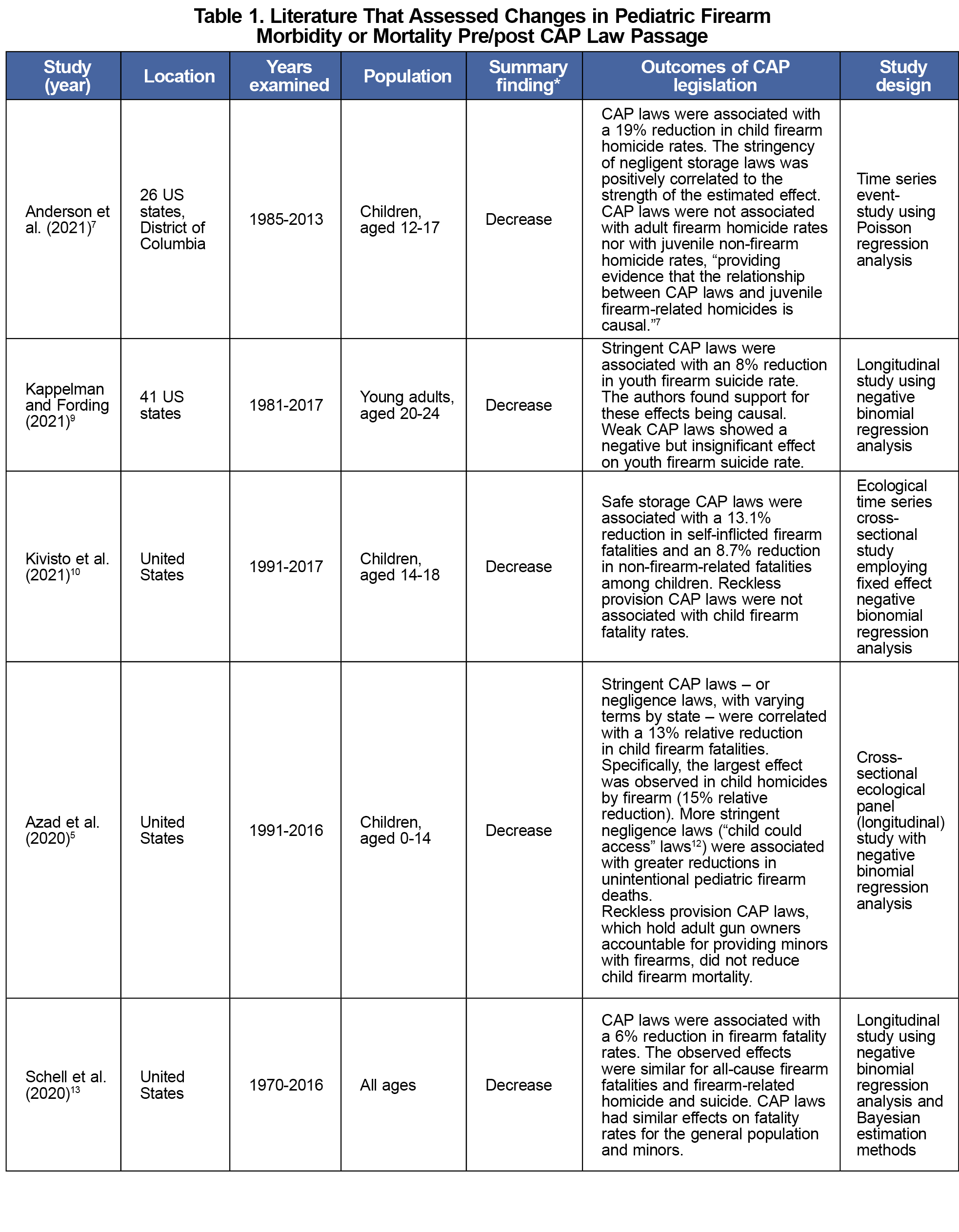

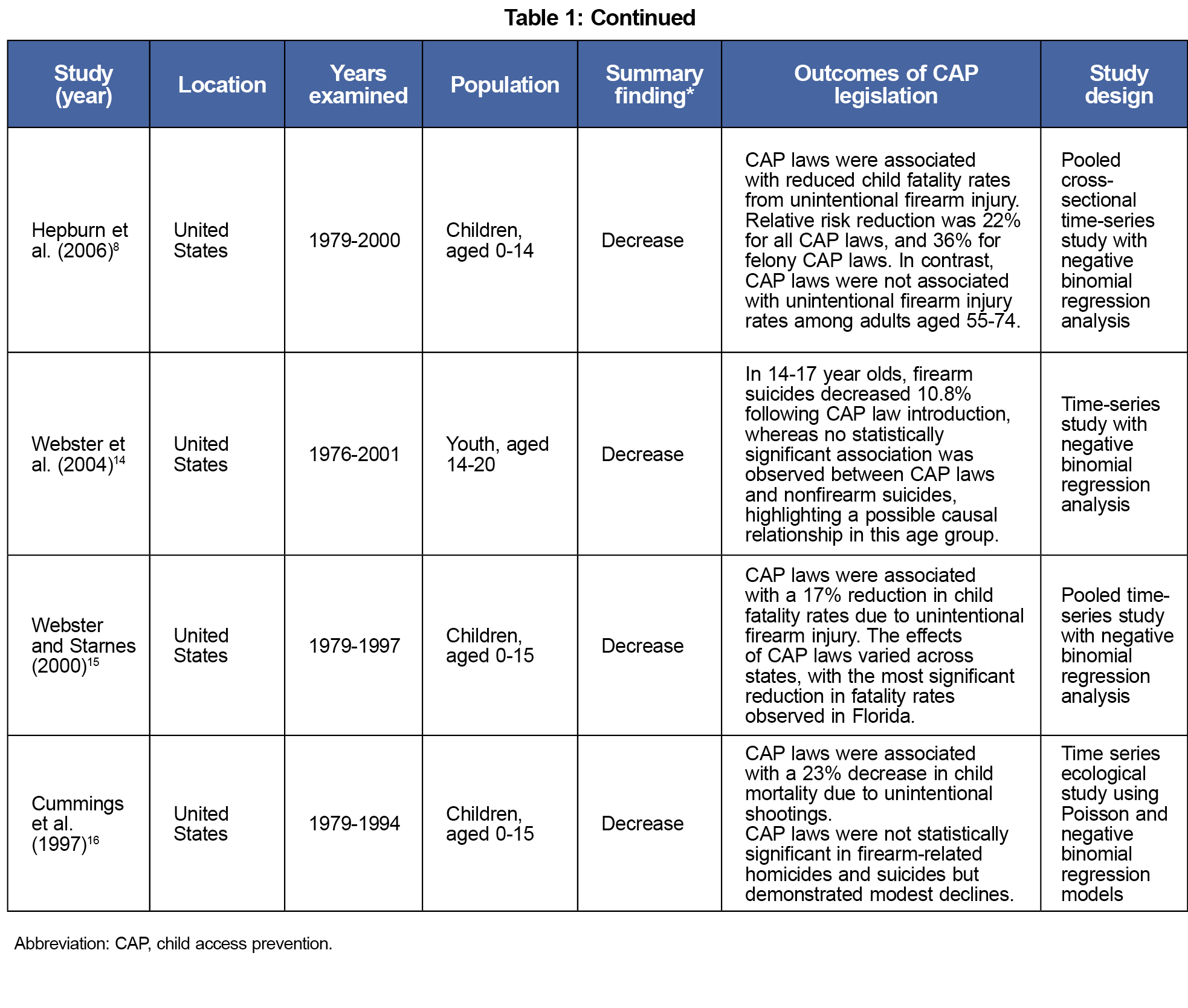

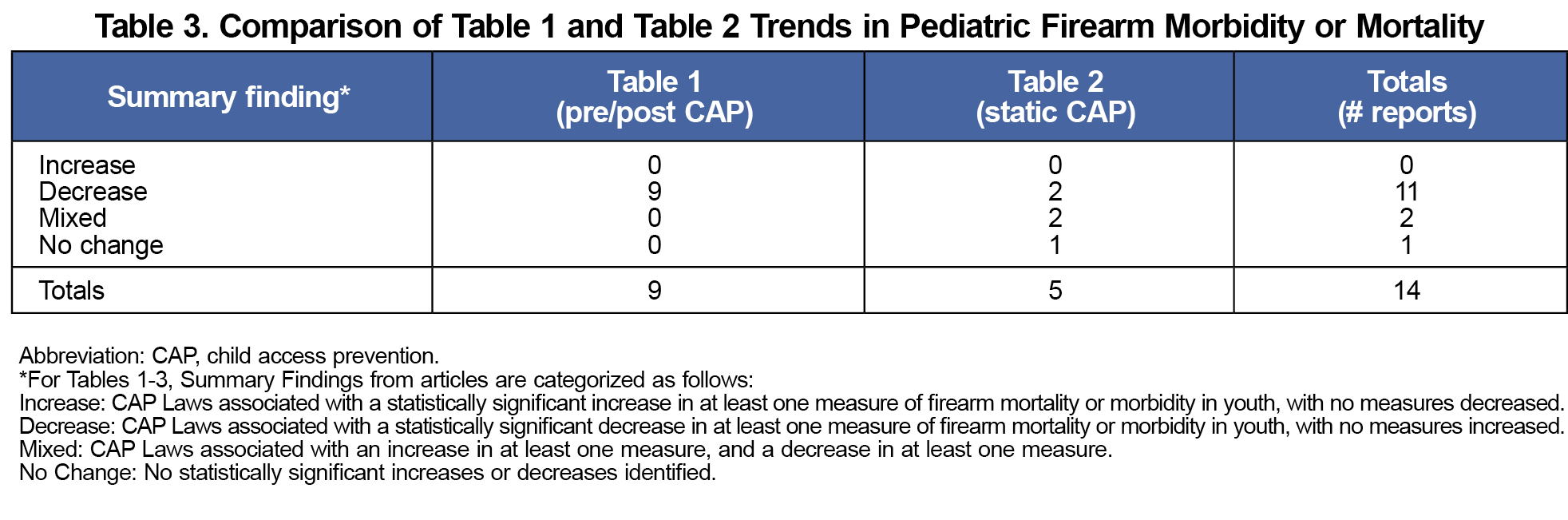

The literature search identified 238 articles. Of those, 14 met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). To test our hypothesis, we summarized and further categorized qualifying reports into those that assessed changes in pediatric firearm morbidity or mortality pre/post-CAP law passage (n=9, Table 1), versus those that made static assessments of associations between CAP legislation and pediatric firearm morbidity/mortality (n=5, Table 2). Table 3 summarizes the results of this analysis.

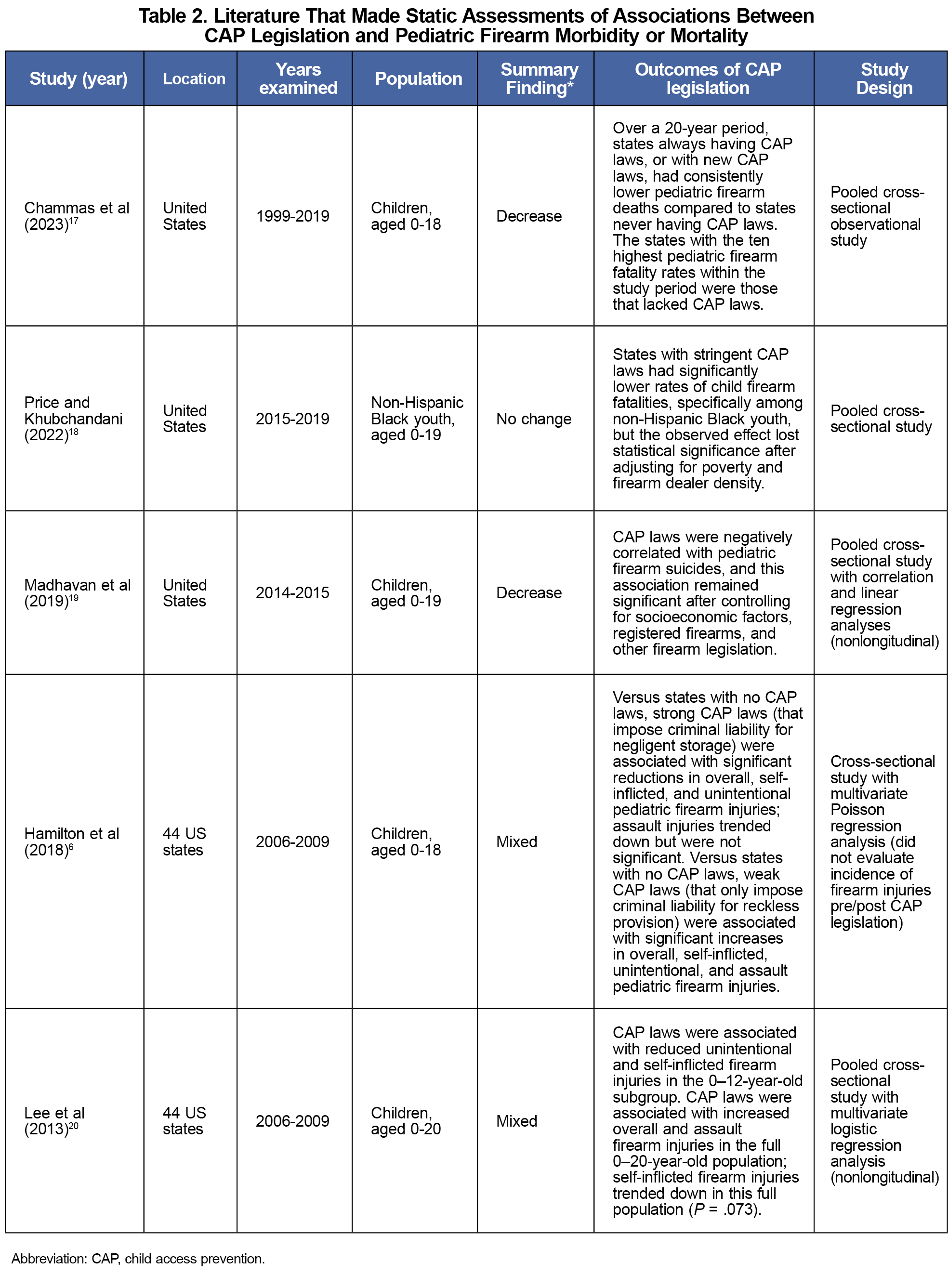

In our analysis, no (0/14) qualifying studies found CAP laws associated with increased pediatric firearm injuries, 11/14 (79%) of qualifying studies found CAP laws associated with decreased pediatric firearm injuries, 2/14 (14%) found mixed results, and 1/14 (7%) found no association (Table 3). However, the studies that analyzed changes in firearm morbidity/mortality before and after CAP legislation (Table 1) unanimously found that CAP laws were associated with decreased youth firearm injuries and/or deaths.

To illustrate, one nontemporal study found that compared to states with no CAP laws, states with strong CAP laws had lower pediatric firearm injuries, whereas states with weak CAP laws had higher pediatric firearm injuries – a mixed result (Table 2).6 In contrast, several pre/post studies found that stronger CAP laws were associated with greater reductions in youth firearm injuries/deaths (versus weaker CAP laws), and no pre/post study found weak CAP laws associated with increased firearm injuries (Table 1).5,7-10

Discussion and Conclusions

In support of our hypothesis, studies that included a longitudinal or temporal element (ie, pre/post analysis of the legislative impact) were found to have the most consistent results (Table 3). Reasons that a non-pre/post analysis may generate spurious results include less firearm legislation, higher firearm ownership, and/or higher gun violence overall in the "weak CAP" versus "no CAP" states that were analyzed, as others discuss.6 Thus, while weaker CAP laws won't hurt and may help reduce pediatric firearm injuries, stronger CAP laws appear more effective.

Further highlighting the importance of pre/post study designs, others argue that longitudinal "difference in difference" studies—that is, "quasi-experimental research designs which estimate the effect of gun policies by comparing the pre–post change in suicide [firearm injury] rates among states that have adopted a gun policy (the treatment group) to the pre–post change in suicide [firearm injury] rates in comparable states that have not adopted that gun policy (the control group)"9 —provide the best evidence of causal effects.9,11 Although proving causality is beyond the scope of this review, many studies in Table 1 and elsewhere11 make credible arguments for causal effects of CAP and other firearm legislation on reducing pediatric firearm injuries.

Our rapid review has limitations. Our search was limited to studies indexed in PubMed, which comprises multiple databases (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/about/) that collectively should encompass most peer-reviewed health literature analyzing the impacts of CAP legislation on pediatric firearm morbidity/mortality. Thus, while some otherwise-qualifying studies not indexed in PubMed may have been missed, we don't believe such occurrences would impact our key findings. Our search terms (“CAP laws,” “firearm,” and “mortality”) may not have identified all articles related to CAP laws and pediatric firearm injuries. A narrative review allows less robust quantitative analysis and conclusions versus a meta-analysis. Finally, the observed statistical relationships between CAP laws and firearm injury can vary by age group and study design, which may guide future research.

The results of our narrative review suggest that CAP legislation appears to be an effective tool for meaningfully reducing youth firearm injuries.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by institutional funds from the State University of New York (SUNY) Upstate Medical University. This paper is subject to the SUNY Open Access Policy.

Presentations: An earlier version of this manuscript (substantial revisions have since occurred) was presented as a poster at the following conference poster sessions:

Charles Ross Memorial Student Research Day, March 29, 2023, Syracuse, NY

Binghamton Biomedical Research Conference, April 25, 2023, Binghamton, NY

Conflict Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no competing interests regarding this paper.

References

- Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) Fatal Injury Reports. 2023. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/

- Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295-304. doi:10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7

- Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Firearm availability and unintentional firearm deaths, suicide, and homicide among 5-14 year olds. J Trauma. 2002;52(2):267-274. doi:10.1097/00005373-200202000-00011

- Goldstick JE, Cunningham RM, Carter PM. Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(20):1955-1956. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2201761

- Azad HA, Monuteaux MC, Rees CA, et al. Child access prevention firearm laws and firearm fatalities among children aged 0 to 14 years, 1991-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):463-469. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6227

- Hamilton EC, Miller CC III, Cox CS Jr, Lally KP, Austin MT. Variability of child access prevention laws and pediatric firearm injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(4):613-619. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001786

- Anderson DM, Sabia JJ, Tekin E. Child access prevention laws and juvenile firearm-related homicides. J Urban Econ. 2021;126:126. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2021.103387

- Hepburn L, Azrael D, Miller M, Hemenway D. The effect of child access prevention laws on unintentional child firearm fatalities, 1979-2000. J Trauma. 2006;61(2):423-428. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000226396.51850.fc

- Kappelman J, Fording RC. The effect of state gun laws on youth suicide by firearm: 1981-2017. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51(2):368-377. doi:10.1111/sltb.12713

- Kivisto AJ, Kivisto KL, Gurnell E, Phalen P, Ray B. Adolescent suicide, household firearm ownership, and the effects of child access prevention laws. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(9):1096-1104. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.442

- Smart R, Morral AR, Ramchand R, et al. The Science of Gun Policy: A Critical Synthesis of Research Evidence on the Effects of Gun Policies in the United States.3rd ed. RAND Corporation; 2023.

- Child Access Prevention and Safe Storage. Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence.Accessed June 13, 2024. https://giffords.org/lawcenter/gun-laws/policy-areas/child-consumer-safety/child-access-prevention-and-safe-storage/

- Schell TL, Cefalu M, Griffin BA, Smart R, Morral AR. Changes in firearm mortality following the implementation of state laws regulating firearm access and use. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(26):14906-14910. doi:10.1073/pnas.1921965117

- Webster DW, Vernick JS, Zeoli AM, Manganello JA. Association between youth-focused firearm laws and youth suicides. JAMA. 2004;292(5):594-601. doi:10.1001/jama.292.5.594

- Webster DW, Starnes M. Reexamining the association between child access prevention gun laws and unintentional shooting deaths of children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1466-1469. doi:10.1542/peds.106.6.1466

- Cummings P, Grossman DC, Rivara FP, Koepsell TD. State gun safe storage laws and child mortality due to firearms. JAMA. 1997;278(13):1084-1086. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550130058037

- Chammas M, Byerly S, Lynde J, et al. Association between child access prevention and state firearm laws with pediatric firearm-related deaths. J Surg Res. 2023;281:223-227. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2022.08.034

- Price JH, Khubchandani J. Child access prevention laws and non-hispanic black youth firearm mortality. J Community Health. 2022.

- Madhavan S, Taylor JS, Chandler JM, Staudenmayer KL, Chao SD. firearm legislation stringency and firearm-related fatalities among children in the US. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(2):150-157. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.02.055

- Lee J, Moriarty KP, Tashjian DB, Patterson LA. Guns and states: pediatric firearm injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(1):50-53. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182999b7a

There are no comments for this article.