Introduction: Existing literature about student-run clinics (SRCs) often focuses on student rather than patient experiences. To begin to gather data on norms and practices at SRCs nationally, this pilot study surveyed faculty leaders from SRCs around the country about metrics such as clinic organization, patient demographics, and care services.

Methods: A 38-question survey was distributed via email to members of the Student Run Free Clinic Faculty Association (SRFCFA) in October 2021. All responses were collected electronically via Qualtrics survey software.

Results: Most SRCs are held at least once weekly in variable physical locations. All SRCs surveyed use an electronic medical record. Student leadership typically rotates annually. Preceptors skew towards generalists rather than specialists. Clinics have variable patient volumes but see majority uninsured and non-English-speaking patient populations. Responses about consistency of result communication, follow-up visits, referrals to specialty care, and management of high-risk patients were mixed. The majority of respondents did not feel that learner experience was prioritized over patient care.

Conclusion: The design and operations of SRCs nationwide is variable and not standardized. There remains a limited understanding of patient experiences and patient-centered outcomes at SRCs, and thus it is difficult to guide best practices. Future efforts to collect patient perspectives and outcomes should be emphasized given the vulnerable populations these clinics serve.

Student-run clinics (SRCs) exist at most United States medical schools.1,2 The most common model is a free or low-cost clinic led and staffed by students with supervision from faculty volunteers. Care can include urgent, chronic, preventative, and/or specialist services.1,2 SRCs primarily serve patients without stable or accessible primary care. The majority of patients are uninsured,1 and historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups are disproportionately represented.2 The reported benefits of student participation in SRCs include working on interprofessional teams,2,3 developing clinical skills,2,4 and increasing student interest in work with underserved populations.1,5 Previously cited areas for improvement include faculty staffing,1 funding,1 and integration into formal curricula.2

Publications about patient experiences and clinical outcomes at SRCs are limited. Some clinics have embarked on quality improvement initiatives including collecting patient satisfaction data,6,7 though these are reported as single-clinic efforts. There is a concerning absence of larger-scale and patient-oriented assessments of SRCs. To begin to gather data on current practices at SRCs, this pilot study surveyed faculty leaders from SRCs around the country.

To our knowledge, there are no existing validated questionnaires specifically geared toward student-run clinics. Thus, we created a unique 38-question survey for this investigation. To use validated survey tools, some questions were derived from pre-existing self-assessment toolkits for hospital and clinic leaders that focused on health equity performance and patient centeredness.8,9-11 We developed additional questions relating specifically to SRC operations. The survey was distributed to members of the Student Run Free Clinic Faculty Association, a group of approximately 200 members, via a shared link within the organization’s email newsletter in October 2021. A reminder email was sent 2 weeks later. The survey closed 4 weeks after initial distribution. Twenty-one individuals completed the survey (10% of total newsletter recipients, 32% of those who opened the newsletter). Each respondent was asked to generate a unique identifier to ensure there were no duplicate responses. All responses were included in the analysis, even if the respondent did not finish the survey. For questions with less than 100% response rate, the denominator was adjusted accordingly. This study was exempted by the University of Rochester’s and University of Wisconsin's Institutional Review Boards.

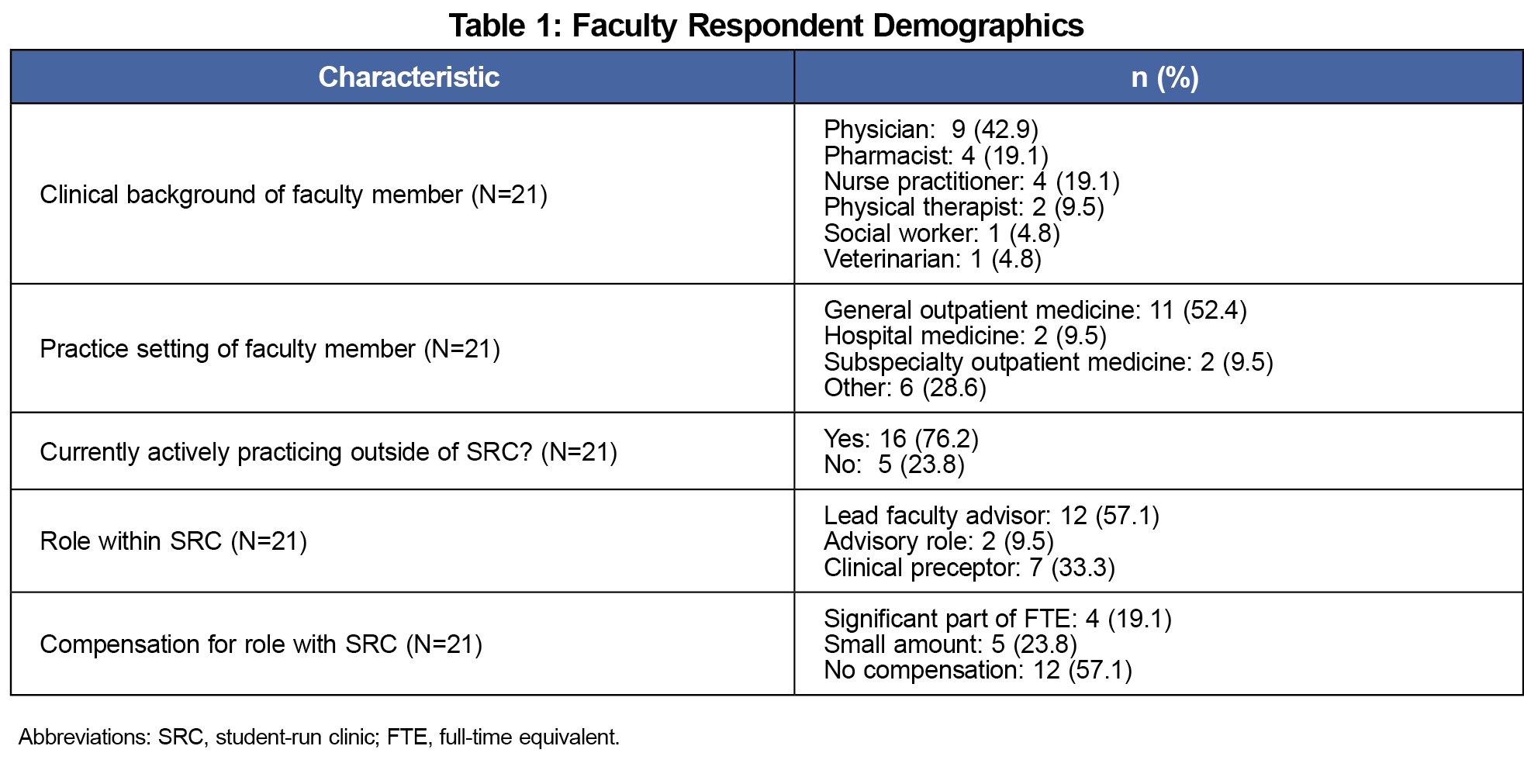

Twenty-one respondents participated in the survey, with demographics outlined in Table 1.

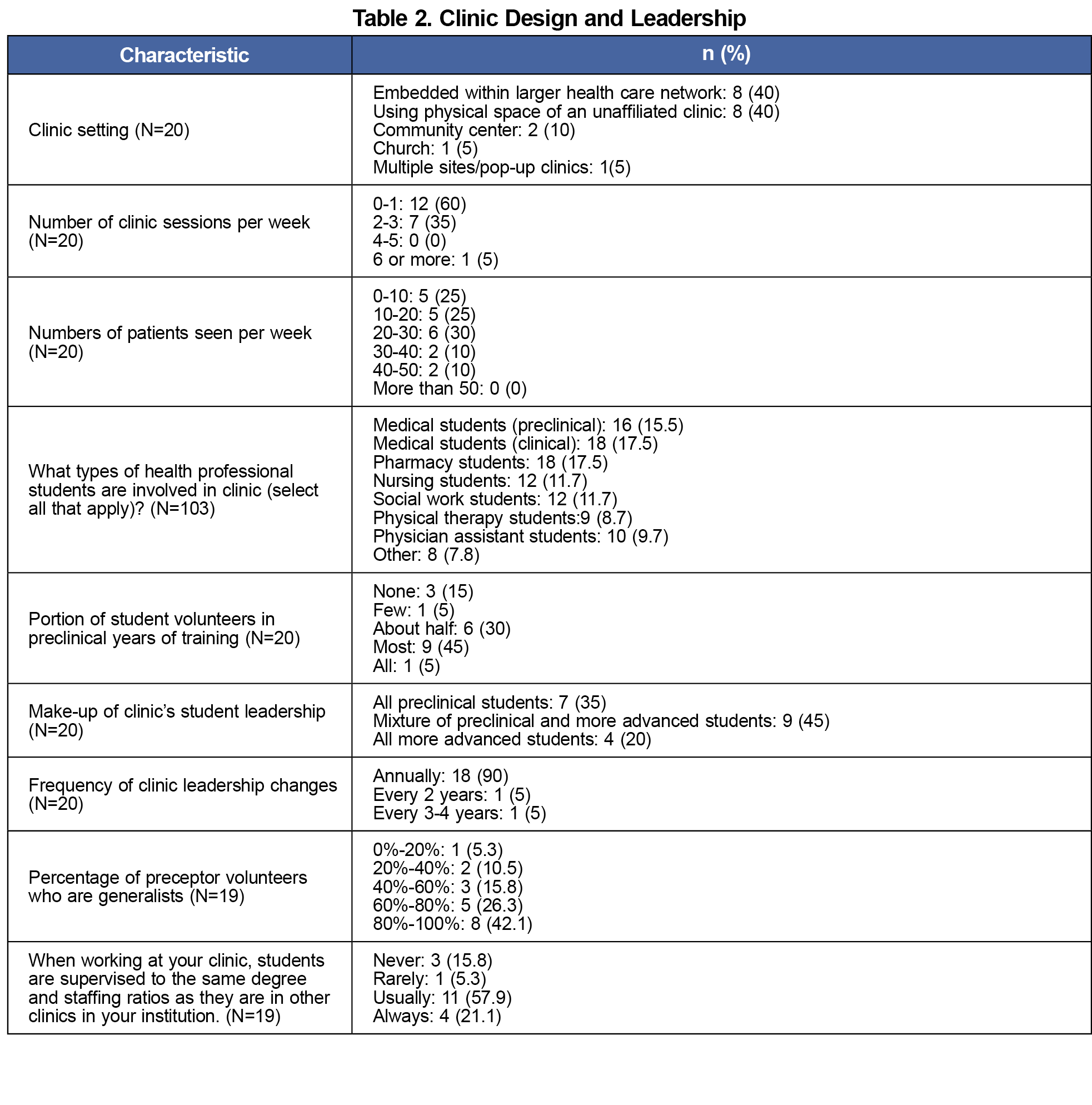

Clinic Design and Leadership

Survey respondents described diverse SRC settings: most (80%) operate in a physical clinic space, while a minority (20%) operate in nonmedical spaces (eg, community center, church, pop-up sites). Faculty reported a typical frequency of 0-1 clinic sessions per week (60% of respondents), though some clinics offer 2-3 sessions weekly (35% of respondents). Patient volumes vary widely with no clinic seeing greater than 50 patients each week. Student involvement draws from multiple disciplines: medicine (majority preclinical), nursing, pharmacy, physician assistant, physical therapy, and social work. Student leadership primarily changes annually (90% of respondents). Clinic preceptors skew toward generalists rather than specialists. Survey respondents described a ratio of staffing and student supervision akin to other clinics within their institution, though this was not consistent across all respondents (Table 2).

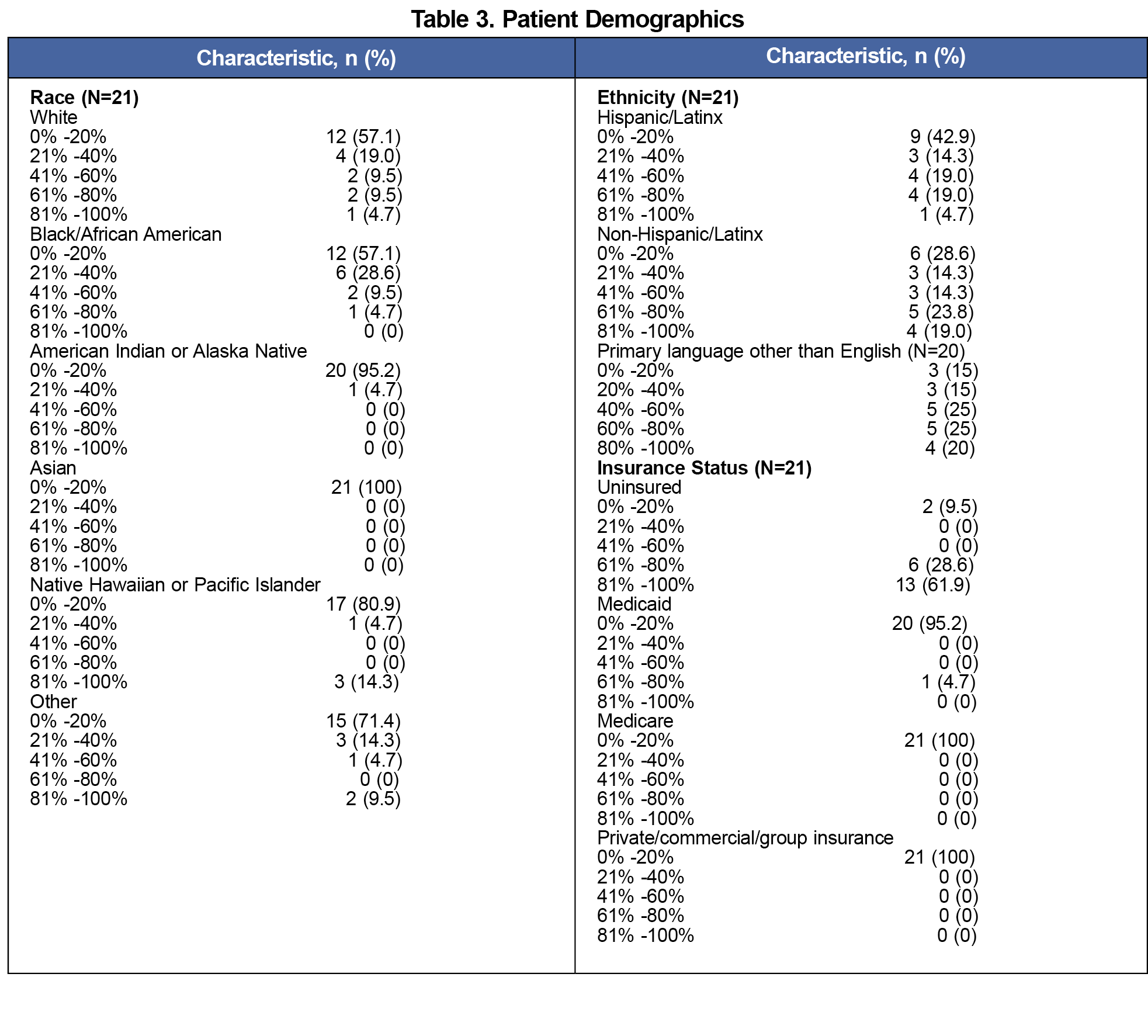

Demographics, Diversity, and Equity

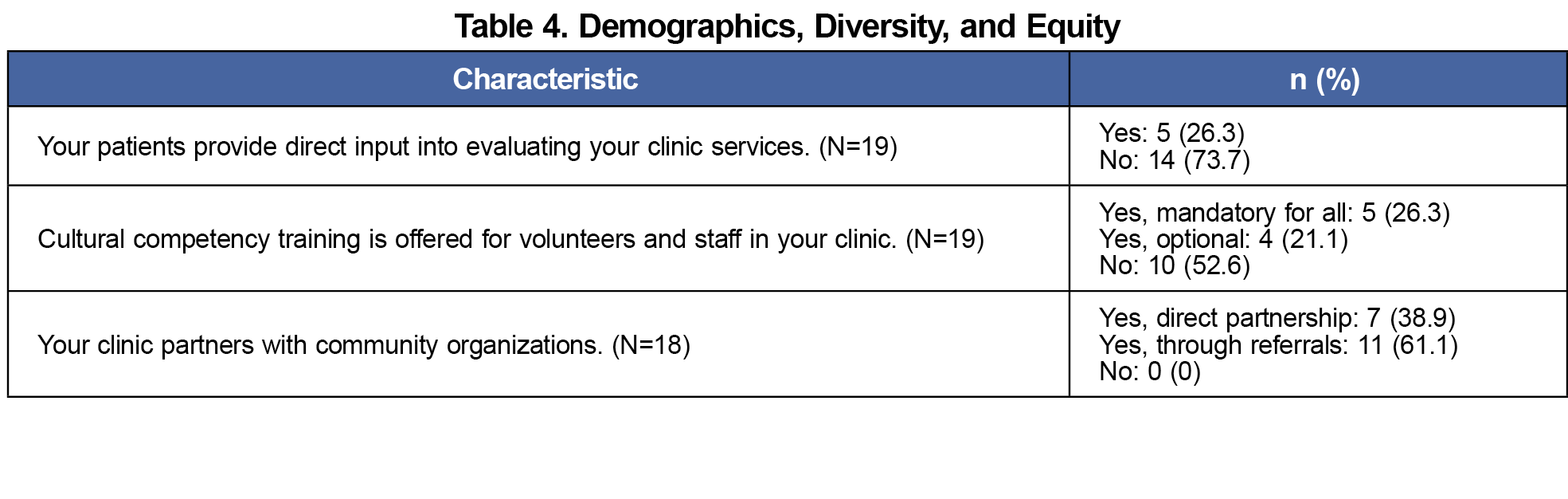

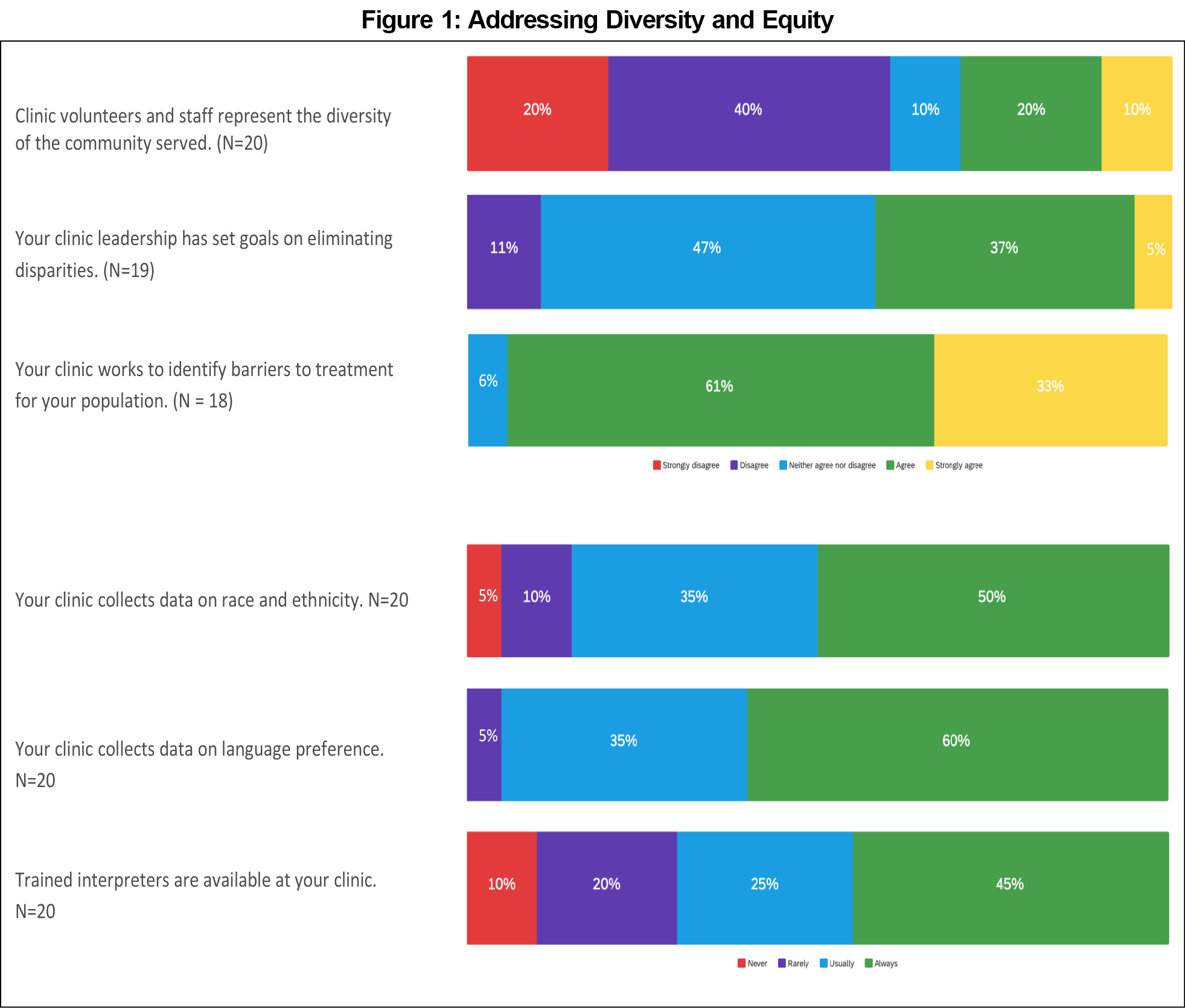

Faculty reported a mix of racial and ethnic patient demographics. More than half of respondents described their SRC patient population as non-English-speaking. Most clinics offer trained interpreters (14/20 [70%] indicating “usually” or always”). Patients are primarily uninsured (19/21 respondents described >60% uninsured). See Table 3 for further breakdown of patient demographics. A minority of respondents reported clinic staff represents the diversity of the community served (40%, 8/20). Answers to additional questions about diversity, equity, and community partnership are in Table 4 and Figure 1.

Operations and Quality Improvement

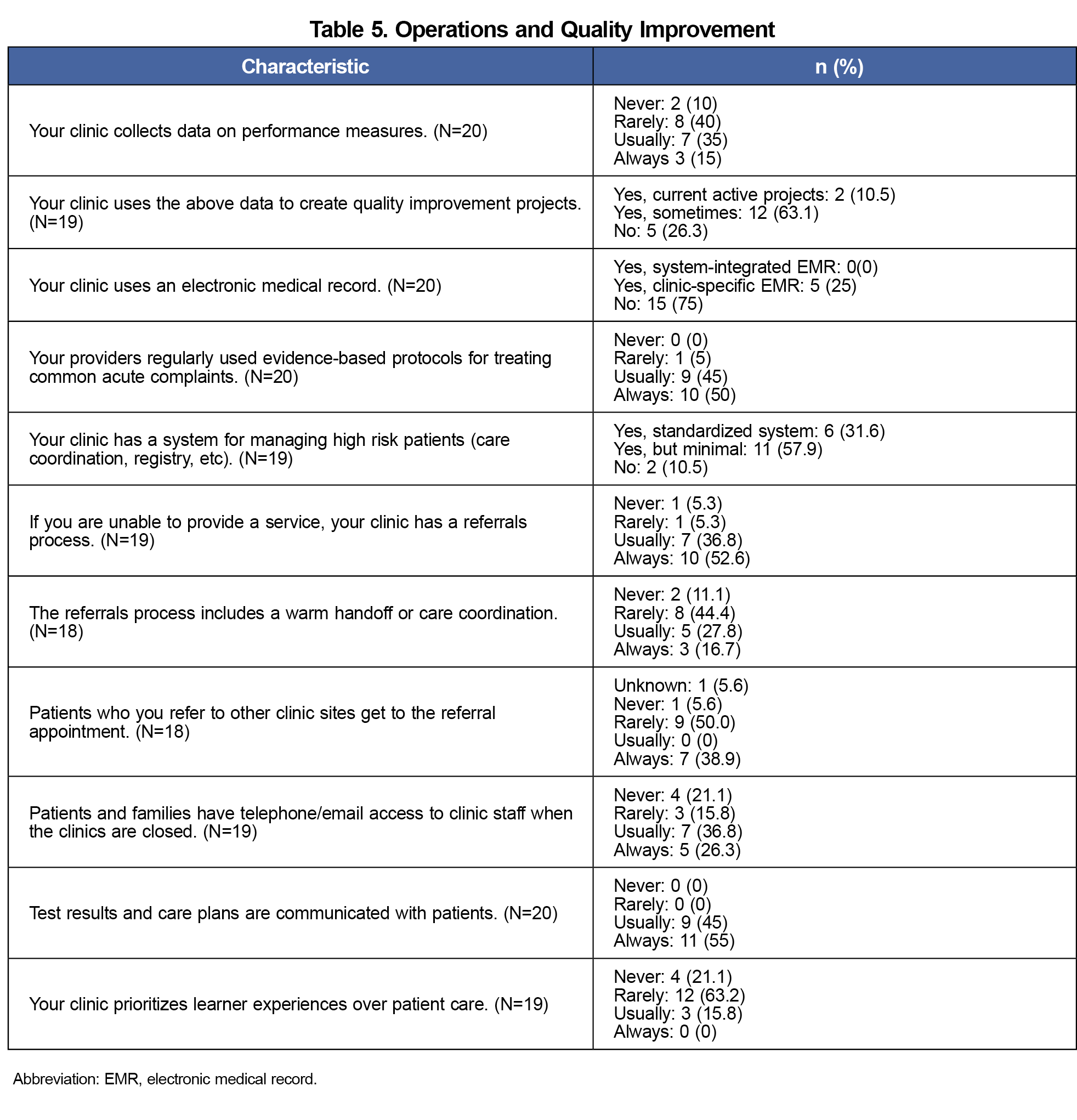

All participating faculty reported use of an electronic medical record at their SRC. Many clinics (14/19, 74%) are engaged in quality improvement work. While many SRCs have systems for management of high-risk patients (17/19, 89%), those systems were primarily described as minimal (11/17, 65%). Two respondents did not know of any system for management of high-risk patients. The majority of respondents (17/19, 89%) described established referral processes to other services, though the reported consistency of care coordination and follow-up for these referrals was mixed. Less than half of surveyed clinics have a system for patient feedback (5/19, 26%). Most respondents did not feel that learner experience was prioritized over patient care (Table 5).

Principal Findings

Most clinics are appropriately supervised by generalists, given the potential breadth of patients’ concerns. Student leadership transitions yearly, thus limiting longer-term initiatives. Care coordination processes including test result communications and referrals often exist, however standardized systems for management of higher-risk patients and follow-up after referrals is lacking. Patient input on clinic services is inconsistent.

Most clinics collect data on patient demographics. Trained interpreters are available at a majority though notably not all clinics, which is especially important as most clinics serve non-English-speaking populations. Similar to other medical settings, the makeup of SRC volunteers does not always represent the diversity of the population served, and further training to address health disparities is needed.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study begins the process of better understanding SRCs' design and operations. The sample size is small and unlikely to be representative. Faculty advisors were chosen as a convenience sample, and responses are limited by selection bias in that only interested faculty advisors likely responded. Based on unique identifiers each respondent generated, there were no known duplicate responses, however it is possible that more than one faculty member from a single clinic responded to the survey. Future studies could improve by directly contacting medical schools, performing qualitative interviews, obtaining data from clinic records rather than faculty recall, and surveying students in addition to faculty. Survey design could be improved by creating more consistent Likert-scale answers for similar question types and defining qualifiers, such as “high-risk patients.” Additional efforts should focus on patient perspectives and patient-centered outcomes, which are difficult to assess objectively when surveying clinic leadership.

The existing literature on SRCs often focuses on student rather than patient experiences. This survey describes additional information surrounding clinical operations and patient care from the faculty perspective only. Based on this survey data as well as published literature, the design and operations of SRCs nationwide is highly variable and likely a function of factors including institutional associations, patient demographics, and available resources. Future efforts to collect patient perspectives as well as patient- and community-centered outcomes will help build the existing knowledge base. This in turn could contribute to SRC best practice recommendations to improve care for the vulnerable patient populations they serve.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lorraine Porcello for her help with literature review.

References

- Smith S, Thomas R III, Cruz M, Griggs R, Moscato B, Ferrara A. Presence and characteristics of student-run free clinics in medical schools. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2407-2410. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.16066

- Rupert DD, Alvarez GV, Burdge EJ, Nahvi RJ, Schell SM, Faustino FL. Student-run free clinics stand at a critical junction between undergraduate medical education, clinical care, and advocacy. Acad Med. 2022;97(6):824-831. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004542

- Lie DA, Forest CP, Walsh A, Banzali Y, Lohenry K. What and how do students learn in an interprofessional student-run clinic? An educational framework for team-based care. Med Educ Online. 2016;21:31900. Published 2016 Aug 5. Doi:doi:10.3402/meo.v21.31900

- Schutte T, Tichelaar J, Dekker RS, van Agtmael MA, de Vries TP, Richir MC. Learning in student-run clinics: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2015;49(3):249-263. doi:10.1111/medu.12625

- Sick B, Zhang L, Weber-Main AM. Changes in health professional students’ attitudes toward the underserved: impact of extended participation in an interprofessional student-run free clinic. J Allied Health. 2017;46(4):213-219.

- Lee JS, Combs K, Pasarica M; KNIGHTS Research Group 2016. Improving efficiency while improving patient care in a student-run free clinic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(4):513-519. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170044

- Lawrence D, Bryant TK, Nobel TB, Dolansky MA, Singh MK. A comparative evaluation of patient satisfaction outcomes in an interprofessional student-run free clinic. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(5):445-450. doi:10.3109/13561820.2015.1010718

- American Society for Healthcare Risk Management of the American Hospital Association. (2015). ASHRM Equity of Care Assessment Tool. ASHRM. Retrieved from https://www.ashrm.org/system/files?file=media/file/2019/06/ASHRM-Equity-of-Care-Assessment-Tool.pdf

- Health Research and Educational Trust, Washington State Hospital Association. (2018, October). HRET Hiin Health Equity Organizational Assessment – wsha.org. WSHA. Retrieved from https://www.wsha.org/wp-content/uploads/Health-Equity-Metric-Guidance_WSHA.pdf

- Institute for Family-Centered Care. (2004). Strategies for leadership, Patient and Family Centered Care, A Hospital Self-Assessment Inventory. American Hospital Association. Retrieved from https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-02/assessment.pdf

- MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation, Group Health Cooperative. (2014). Patient Centered Medical Home Assessment. Safety Net Medical Home Initiative. Retrieved from https://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/

There are no comments for this article.