Introduction: Medical students experience high levels of stress, burnout, depression, suicidal ideation, and compassion fatigue. Mindfulness interventions in this population have demonstrated improvement in psychological outcomes. However, it is unclear if these improvements are maintained. Evaluation of changes in lifestyle behaviors may provide insight into factors that sustain improvements. Specific aims of this study were to (1) assess feasibility and acceptability of an innovative, virtual program involving experiential learning, social support, and motivational interviewing; and (2) evaluate preliminary healthy lifestyle behaviors and psychological outcomes from preprogram to postprogram and 4-week follow-up.

Methods: We used a mixed-methods approach to investigate feasibility, acceptability, and effects of the virtual program using validated measures and open-ended questions. Participants were 20 first- and second-year medical students at one Midwestern US medical college who participated between October 2020 and December 2020. Participants were enrolled in one of two groups for the 8-week program via Webex. Participants completed surveys at preprogram, postprogram, and 4-week follow-up. They also completed weekly home practice assessments.

Results: Nineteen of 20 participants completed the program (95% retention rate). All participants attended six or more sessions. Repeated measures analysis of variance revealed that participants had significant improvements in healthy lifestyle behaviors, burnout, self-compassion, and stress across time. Results were supported by qualitative themes of increased social support, wellness skills, and overall positive experiences.

Conclusion: Findings suggest that the virtual program was feasible and acceptable to medical students, and improved healthy lifestyle behaviors and psychological outcomes that were maintained or increased at 4-week follow-up.

Medical students experience high levels of stress, burnout, depression, suicidal ideation, and compassion fatigue.1-5 Medical students’ mental health tends to decline over time in medical school and may diminish their ability to provide compassionate care.4,6-9

Some medical schools have implemented wellness programs to reduce deleterious effects of medical eduation.10-13 Such programs often focus on stress management skills and mindfulness.8,14-17 Evaluations of these programs have demonstrated significant pre/post improvements in depression, stress, anxiety, compassion, resilience, empathy, self-compassion, and burnout.13,18-21

However, it is unclear if these immediate psychological benefits are sustained. There is also a lack of research evaluating effects of such programs on habitual healthy lifestyle behavior. Healthy lifestyle behaviors include health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, spiritual growth, interpersonal relations, and stress management. These may be key factors influencing maintenance of skills and sustaining benefits. Therefore, we developed a new intervention, the Self-compassion, Yoga, and Mindfulness for Burnout: Integrating Online Sessions and Interpersonal Support (SYMBIOSIS) program. Specific aims of our study of this program were to (1) assess feasibility and acceptability of the virtual SYMBIOSIS program for medical students, and (2) evaluate preliminary healthy lifestyle behaviors and psychological outcomes from preprogram to postprogram and 4-week follow-up.

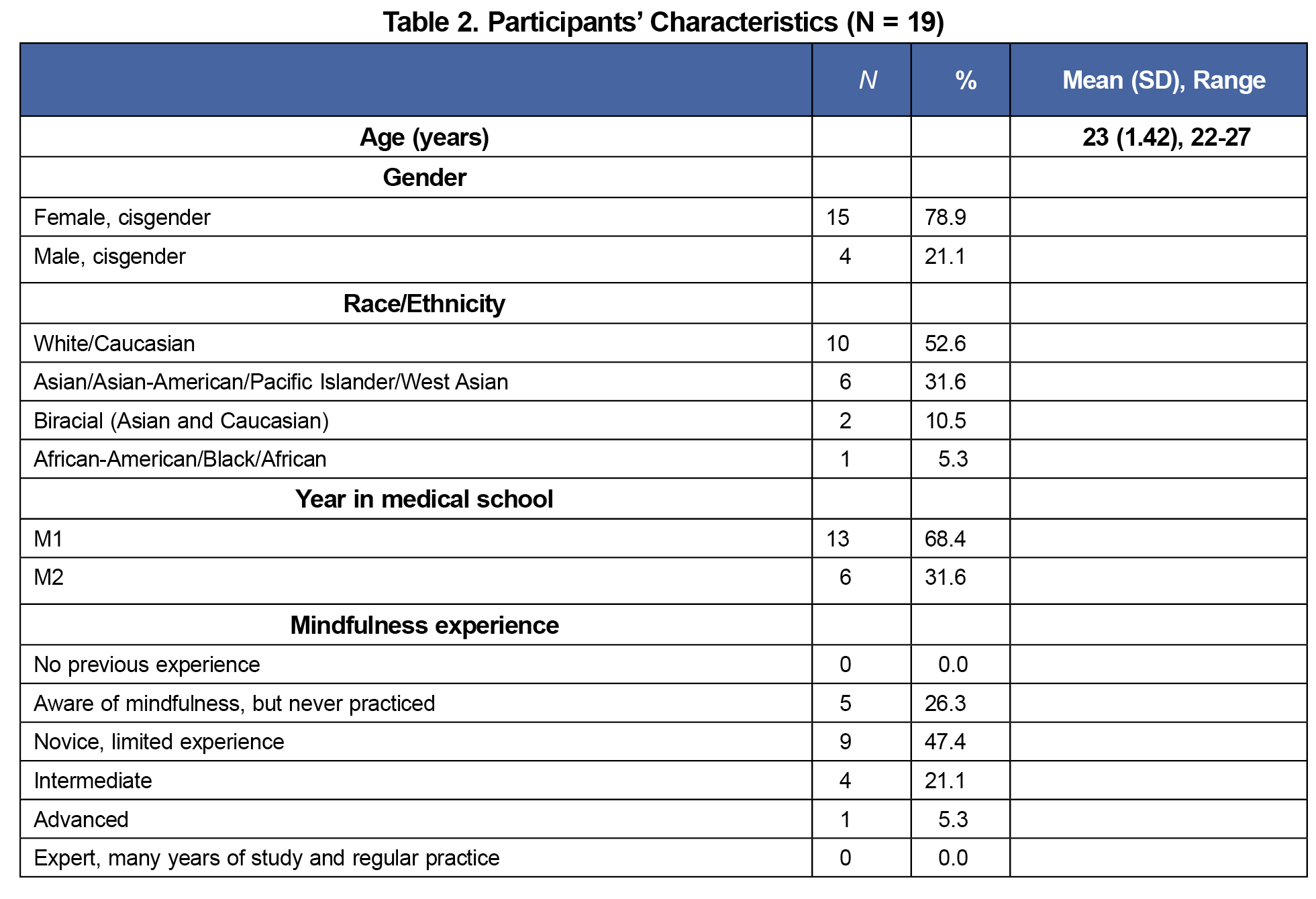

We recruited medical students (n=20) at a Midwestern US medical college through email. Participants completed an online screening survey and consent form. Participants were enrolled into one of two groups based on availability and compensated with $30 Amazon e-gift cards. Affiliated institutions provided institutional review board approval.

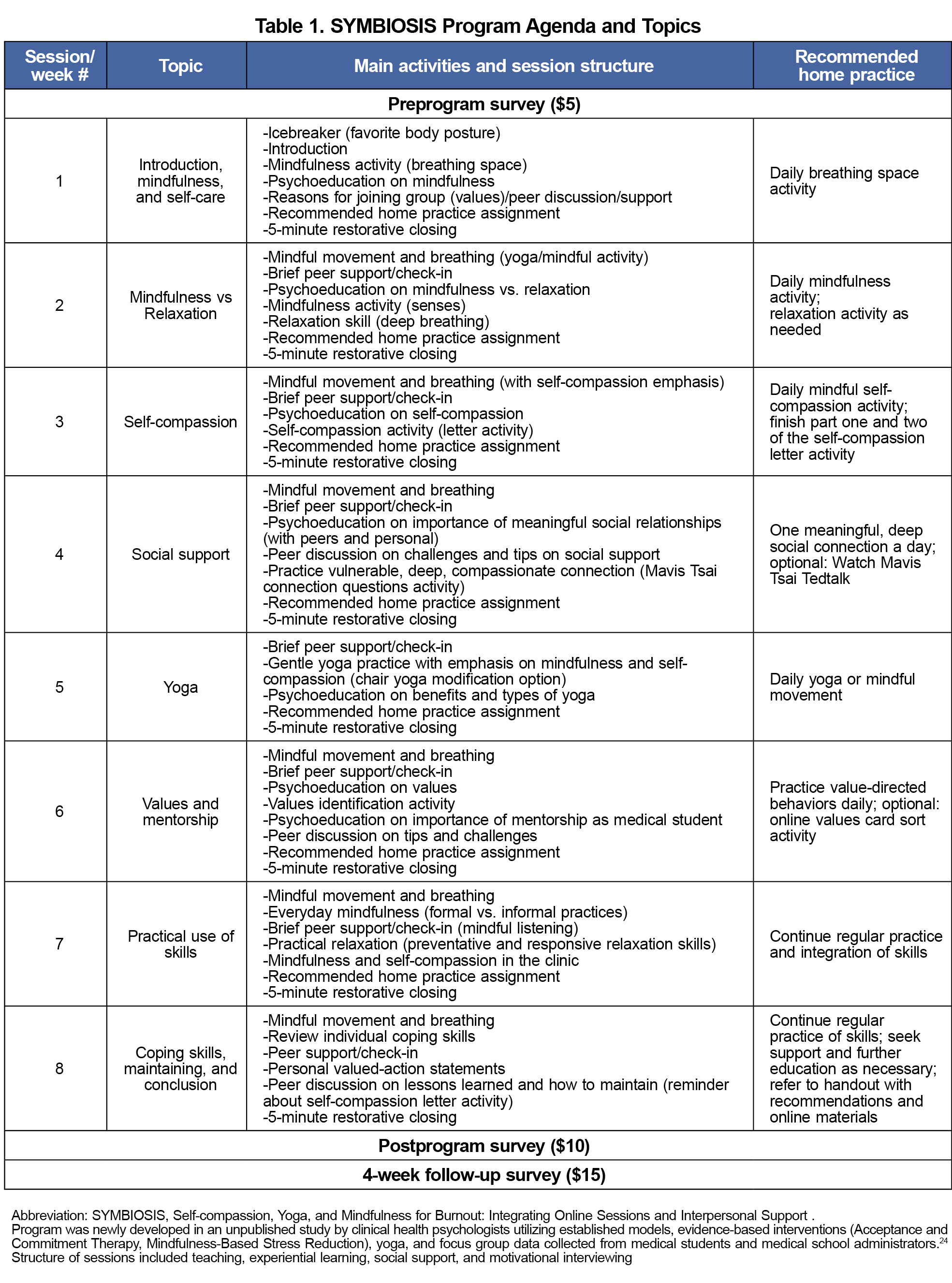

We developed the innovative program, SYMBIOSIS (outlined in Table 1) utilizing established models, evidence-based interventions, and focus group data collected from medical students.13,20-24 The program was optional and not affiliated with the medical school. Structure of sessions included teaching, experiential learning, social support, and motivational interviewing. The program consisted of 8 weekly, 50-minute synchronous virtual sessions via Webex. Two groups ran consecutively between October 2020 and December 2020. Sessions were cofacilitated by two clinical psychology doctoral trainees. Both facilitators were also certified yoga teachers.

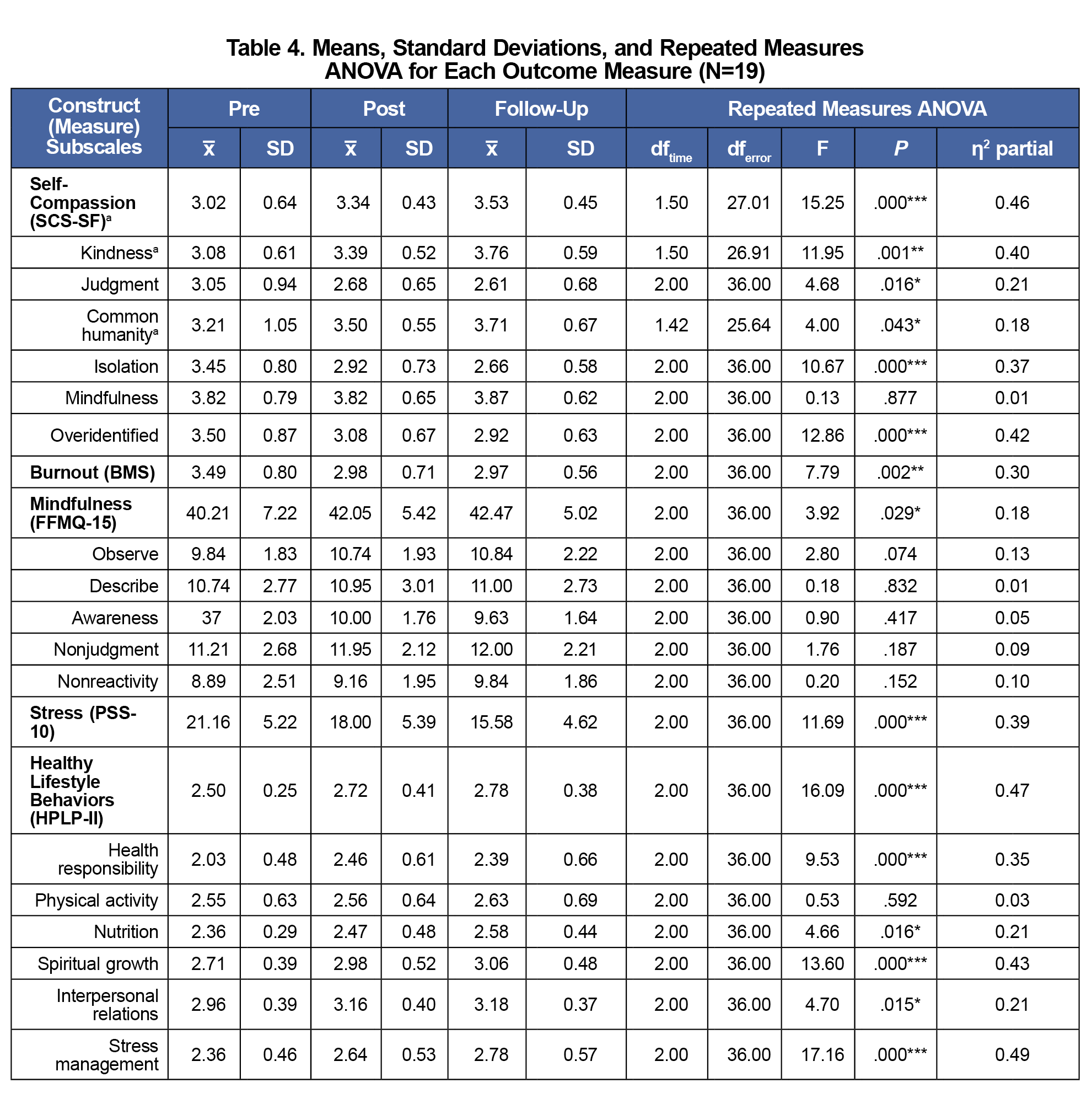

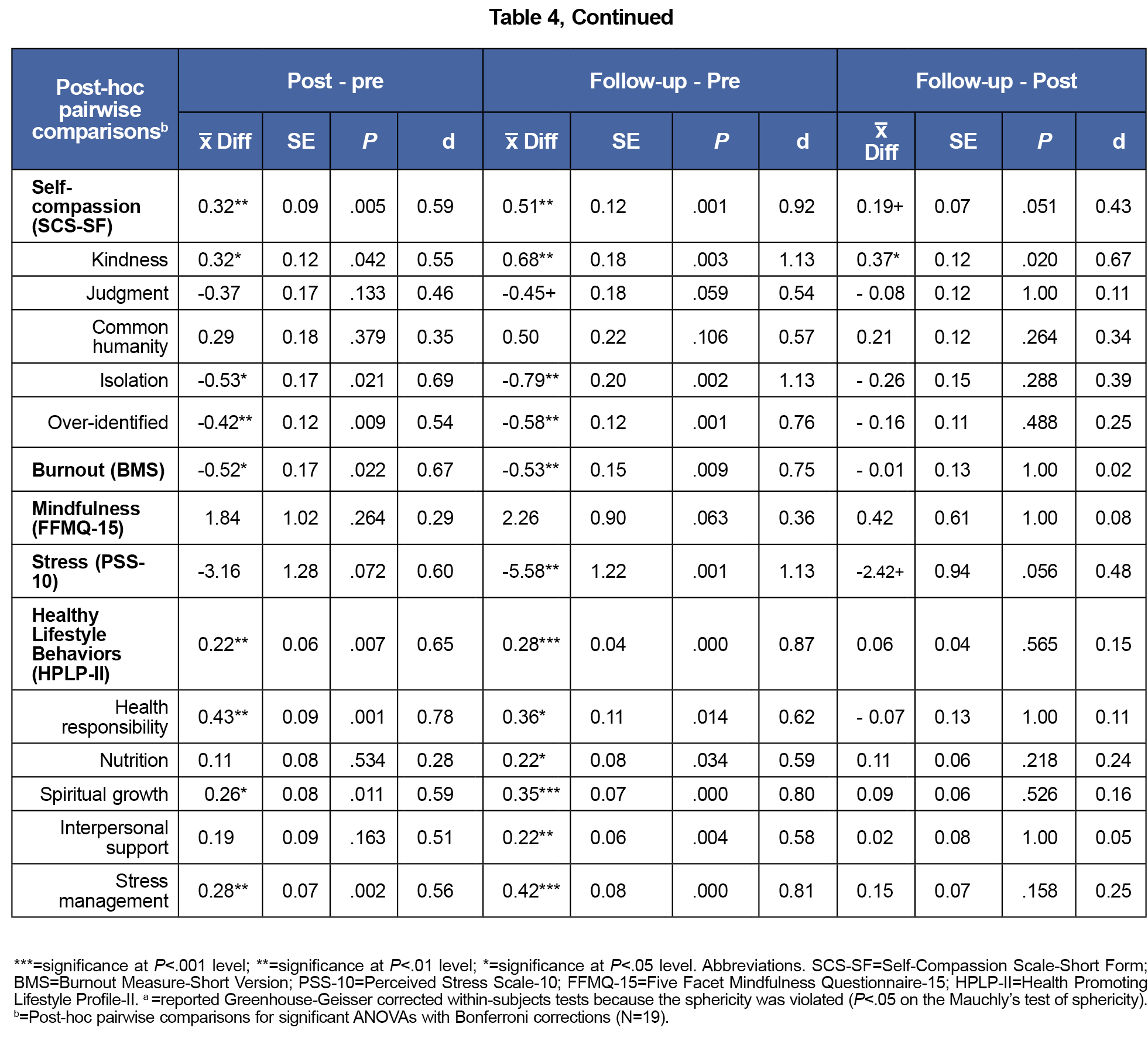

Participants completed the online surveys at preprogram, postprogram, and 4-week follow-up. All surveys measured the following constructs utilizing validated measures (Table 4): healthy lifestyle behaviors (subscales: health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, spiritual growth, interpersonal relations, stress management),25 self-compassion,26-27 burnout,28 stress,29-31 and mindfulness.32-33 The preprogram survey included demographic questions. The postprogram survey included 5-point Likert-scaled and open-ended questions to assess feasibility and acceptability.34-35 Both cofacilitators completed a treatment fidelity checklist (14 adapted items) after each session.36

Adequate treatment fidelity was assumed if at least 80% of intervention items were included in each session.36 Feasibility was assessed with enrollment, retention, and attendance rates. Feasibility and acceptability results included averaged quantitative scores and themed qualitative responses (two independent raters). Repeated measures analyses of variance were conducted for all outcome measures. Significant main effects were evaluated with pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction. We used Mauchly’s test to evaluate each measure. For measures violating sphericity, we adjusted degrees of freedom using Greenhouse-Geisser correction.

Twenty participants enrolled, with 10 in each group; 19 participants completed program. Participant demographics are shown Table 2. Treatment fidelity results met the cutoff for fidelity adherence (96% agreement).

Full recruitment (n=20) was met within 4 days. All participants who completed the intervention (n=19) attended at least six of eight sessions (average attendance rate=90%; retention rate=95%). Participants rated the program content as “Very easy to use,” and the overall program as “Very helpful,” “Very valuable,” and participants were “Very satisfied” (0=not at all, 5=extremely).

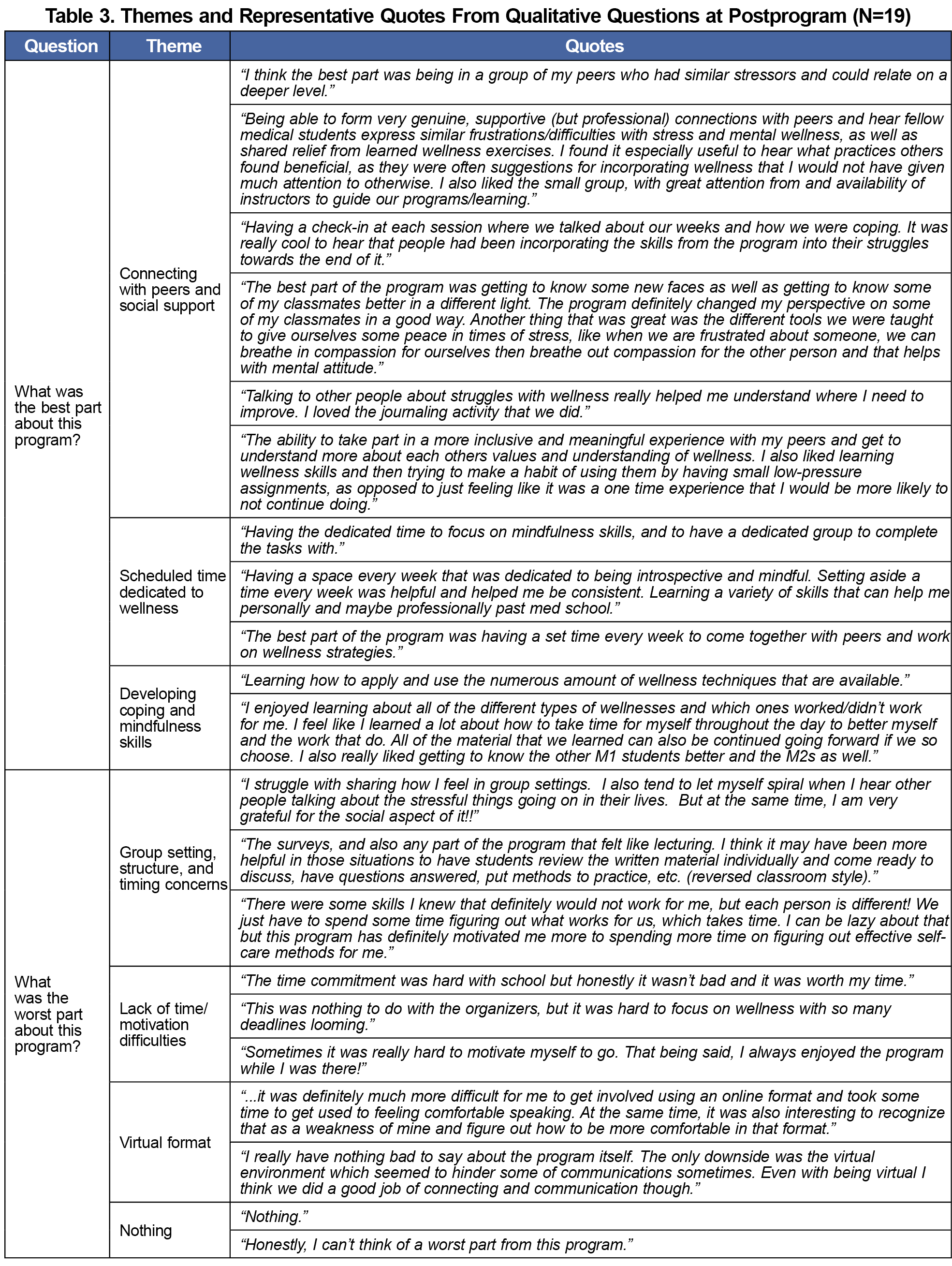

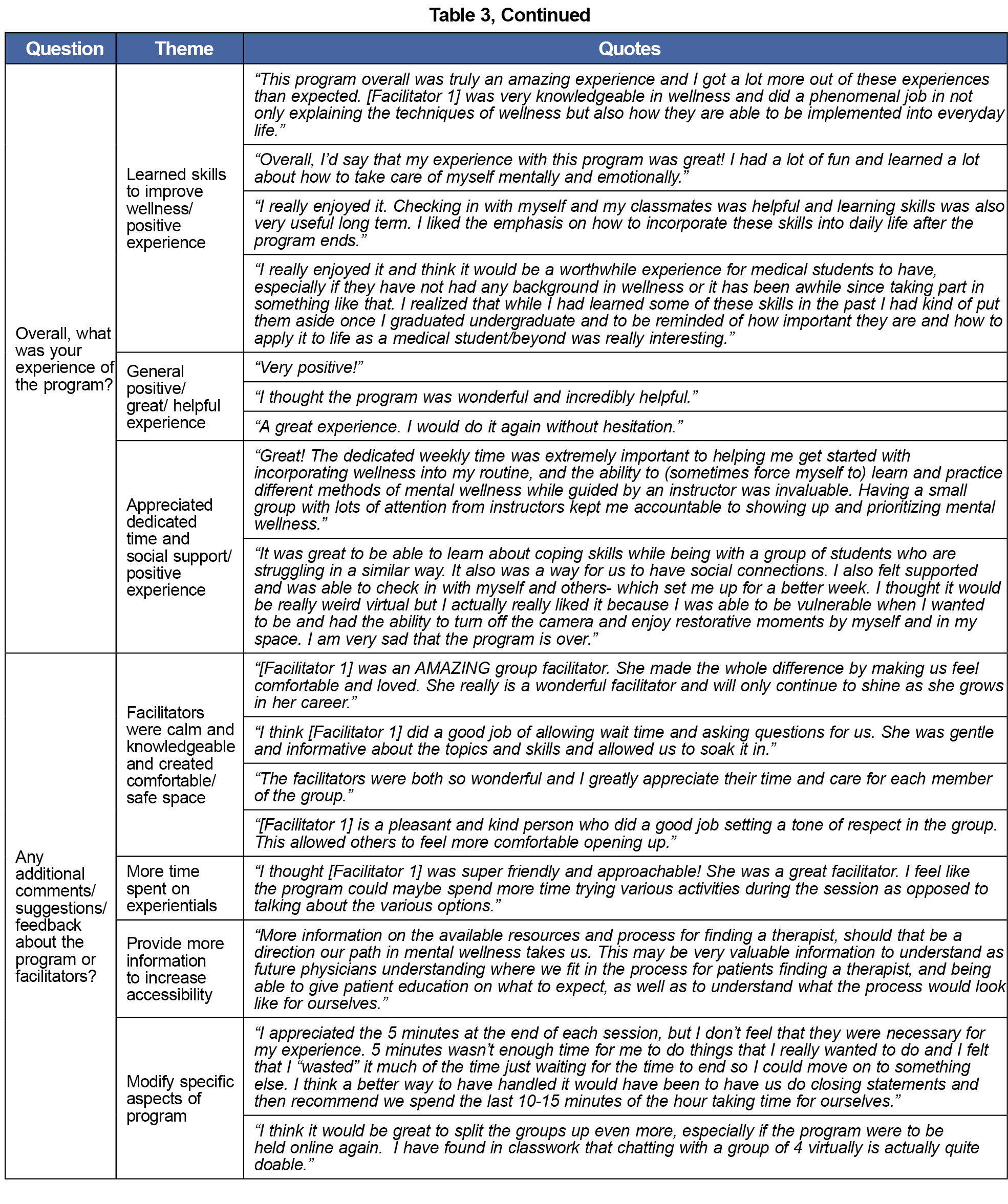

Qualitive responses are shown in Table 3. Themes regarding the most appreciated aspects of program included peer/social support; scheduled time dedicated to wellness; developing coping and mindfulness skills; and facilitators were calm, knowledgeable, and created a safe space. Themes regarding least appreciated parts of program included group setting/structure/timing concerns, lack of time/other responsibilities, and virtual format. All participants reported an overall positive experience.

Table 4 summarizes main outcome data. Participants reported significant improvements in healthy lifestyle behaviors (pre/post: P<.01, d=.65; pre-follow-up: P<.001, d=.87), self-compassion (pre/post: P<.01, d=.59; pre-follow-up: P<.01, d =.92), burnout (pre/post: P<.05, d=.67; pre-follow-up: P<.01, d=.75), and perceived stress (pre-follow-up: P<.01, d=1.13). No changes in mindfulness were observed.

Results indicated the SYMBIOSIS virtual program was both feasible and acceptable to medical students. Compared to similar studies, we obtained stronger feasibility results.35,37 Our retention and attendance rates mirror rates in well-funded, integrated, in-person programs.38 This is promising for medical schools interested in smaller-scale virtual programs that are effective, accessible, and affordable.

The program demonstrated significant improvements in healthy lifestyle behaviors (health responsibility, nutrition, spiritual growth, interpersonal support, stress management), self-compassion, burnout, and stress. The program did not target improving nutrition, spiritual growth, or health responsibility, yet participants also reported significant improvements in these areas. All improvements occurred pre/post and continued to improve at 4-week follow-up. Given that effects sizes improved to a greater extent at follow-up, this suggests that participants continued to utilize and benefit from the program after conclusion. This may be due to the program’s focus on integrating practical, routine wellness practices into daily life across time and improvements in healthy lifestyle behaviors. Results were comparable to similar trials and meta-analytic findings, with several of our effect sizes being larger.12-13,21,35,39-44 This is notable given that our program was virtual, not part of curriculum or for credit, and conducted by a research group not affiliated with the medical school.

Our study demonstrates positive outcomes within a virtual format, which has meaningful implications. Virtual formats increase accessibility for decentralized programs with students in several geographical areas. It also allows opportunity for cross-medical school interventions. The program structure could easily accommodate booster sessions over time, specifically targeting times of increased risk of stress and burnout.

Limitations include small sample size, participants from one university, self-selection, lack of control group, and potential history effects from the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors limit causal inferences and generalizability of results.

Lower levels of stress and burnout are correlated with better quality of life, mental health, job performance, patient care, and fewer medical errors.14,45-52 Our study supports that programs like SYMBIOSIS may benefit medical students personally and professionally.

These findings suggest that an 8-week virtual wellness intervention was acceptable, feasible, and also improved healthy lifestyle behaviors, self-compassion, burnout, and stress in medical students at postprogram and continued to improve at 4-week follow-up. In future research, it will be important to investigate effects of SYMBIOSIS on academic performance and clinical skill acquisition. Additionally, exploration of specific components and longer-term effects of the SYMBIOSIS program are warranted.

References

- Arnold PJ, Romary DJ. Compassion fatigue: A medical student experience. Acad Psychiatry. 2023;47(2):219-220. doi:10.1007/s40596-022-01666-5

- Maddalena NCP, Lucchetti ALG, Moutinho ILD, Ezequiel ODS, Lucchetti G. Mental health and quality of life across 6 years of medical training: A year-by-year analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2023;00(0):207640231206061. doi:10.1177/00207640231206061

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

- Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):996-1009. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214-2236. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17324

- Mittal R, Su L, Jain R. COVID-19 mental health consequences on medical students worldwide. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021;11(3):296-298. doi:10.1080/20009666.2021.1918475

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ. 2004;38(9):934-941. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01911.x

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(12):1613-1622. doi:10.4065/80.12.1613

- Vollmer-Conna U, Beilharz JE, Cvejic E, et al. The well-being of medical students: A biopsychosocial approach. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020;54(10):997-1006. doi:10.1177/0004867420924086

- Edmonds VS, Chatterjee K, Girardo ME, Butterfield RJ III, Stonnington CM. Evaluation of a novel wellness curriculum on medical student wellbeing and engagement demonstrates a need for student-driven wellness programming. Teach Learn Med. 2023;35(1):52-64. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.2004415

- Shiralkar MT, Harris TB, Eddins-Folensbee FF, Coverdale JH. A systematic review of stress-management programs for medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):158-164. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.12010003

- Daya Z, Hearn JH. Mindfulness interventions in medical education: A systematic review of their impact on medical student stress, depression, fatigue and burnout. Med Teach. 2018;40(2):146-153. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1394999

- Wasson RS, Barratt C, O’Brien WH. Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on self-compassion in health care professionals: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness (N Y). 2020;11(8):1914-1934. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01342-5

- Shanafelt T, Dyrbye L. Oncologist burnout: causes, consequences, and responses. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1235-1241. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7380

- Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4(1):33-47. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.American Psychological Association; 2009.

- Segal ZV, Teasdale J. 2018. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression.Guilford Publications; 2018.

- Buizza C, Ciavarra V, Ghilardi A. A systematic narrative review on stress-management interventions for medical students. Mindfulness (N Y). 2020;11(9):2055-2066. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01399-2

- Sperling EL, Hulett JM, Sherwin LB, Thompson S, Bettencourt BA. The effect of mindfulness interventions on stress in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18(10):e0286387. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0286387

- Yusoff MSB. Interventions on medical students’ psychological health: A meta-analysis. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2014;9(1):1-13. doi:10.1016/j.jtumed.2013.09.010

- Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47-54. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0197-5

- Wight D, Wimbush E, Jepson R, Doi L. Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(5):520-525. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-205952

- Saoji AA. Yoga: A strategy to cope up stress and enhance wellbeing among medical students. N Am J Med Sci. 2016;8(4):200-202. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.179962

- Wasson RS. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Effectiveness of a Pilot Online Mindful Self-Compassion Program for Medical Students. 2022. Doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green State University.

- Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs Res. 1987;36(2):76-81. doi:10.1097/00006199-198703000-00002

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2(3):223-250. doi:10.1080/15298860309027

- Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(3):250-255. doi:10.1002/cpp.702

- Malach-Pines A. The burnout measure, short version. Int J Stress Manag. 2005;12(1):78-88. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.12.1.78

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress.J Health Soc Beh; 1983:385-396.

- Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, eds. The Claremont symposium on applied social psychology: The social psychology of health.Sage Publications; 1988.

- Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2012;6(4):121-127. doi:10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, et al. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment. 2008;15(3):329-342. doi:10.1177/1073191107313003

- Gu J, Strauss C, Crane C, et al. Examining the factor structure of the 39-item and 15-item versions of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire before and after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with recurrent depression. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(7):791-802. doi:10.1037/pas0000263

- Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):108. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3

- Greeson JM, Toohey MJ, Pearce MJ. An adapted, four-week mind-body skills group for medical students: reducing stress, increasing mindfulness, and enhancing self-care. Explore (NY). 2015;11(3):186-192. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2015.02.003

- Johnson CR, Handen BL, Butter E, et al. Development of a parent training program for children with pervasive developmental disorders. Behav Interv. 2007;22(3):201-221. doi:10.1002/bin.237

- Danilewitz M, Bradwejn J, Koszycki D. A pilot feasibility study of a peer-led mindfulness program for medical students. Can Med Educ J. 2016;7(1):e31-e37. doi:10.36834/cmej.36643

- Slavin SJ, Schindler DL, Chibnall JT. Medical student mental health 3.0: improving student wellness through curricular changes. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):573-577. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000166

- Wei CN, Harada K, Ueda K, Fukumoto K, Minamoto K, Ueda A. Assessment of health-promoting lifestyle profile in Japanese university students. Environ Health Prev Med. 2012;17(3):222-227. doi:10.1007/s12199-011-0244-8

- Norouzinia R, Aghabarari M, Kohan M, Karimi M. Health promotion behaviors and its correlation with anxiety and some students’ demographic factors of Alborz University of Medical Sciences. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2013;2(4):39-49.

- Nacar M, Baykan Z, Cetinkaya F, et al. Health promoting lifestyle behaviour in medical students: a multicentre study from Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(20):8969-8974. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.20.8969

- Mašina T, Madžar T, Musil V, Milošević M. Differences in Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile among Croatian medical students according to gender and year of study. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56(1):84-91. doi:10.20471/acc.2017.56.01.13

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X

- Jayewardene WP, Lohrmann DK, Erbe RG, Torabi MR. Effects of preventive online mindfulness interventions on stress and mindfulness: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prev Med Rep. 2016;5:150-159. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.013

- Hodkinson A, Zhou A, Johnson J, et al. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;378:e070442. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-070442

- Wang X, Li C, Chen Y, et al. Relationships between job satisfaction, organizational commitment, burnout and job performance of healthcare professionals in a district-level health care system of Shenzhen, China. Front Psychol. 2022;13:992258. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992258

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Owoc J, Mańczak M, Tombarkiewicz M, Olszewski R. Burnout, well‑being, and self‑reported medical errors among physicians. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021;131(7-8):626-632. doi:10.20452/pamw.16033

- Brazeau CM, Schroeder R, Rovi S, Boyd L. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med. 2010;85(10)(suppl):S33-S36. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4c47

- Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH. Nurse burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(4):288-298. doi:10.1002/nur.20383

- Trockel MT, Menon NK, Rowe SG, et al. Assessmetn of physician sleep and wellness, burnout, and clinically significant medical errors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028111. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28111

- Asante JO, Li MJ, Liao J, Huang YX, Hao YT. The relationship between psychosocial risk factors, burnout and quality of life among primary healthcare workers in rural Guangdong province: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):447. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4278-8

There are no comments for this article.