Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic encouraged widespread implementation of telemedicine. With the increased normalization of telemedicine in clinical practice, the authors sought to characterize telemedicine training during family medicine clerkships after the return to in-person care.

Methods: Data were collected as part of the 2023 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors (CDs). Along with baseline demographics about the clerkship and themselves, CDs answered which Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) telehealth competencies were taught during family medicine clerkships and indicated challenges related to involving medical students in telemedicine visits.

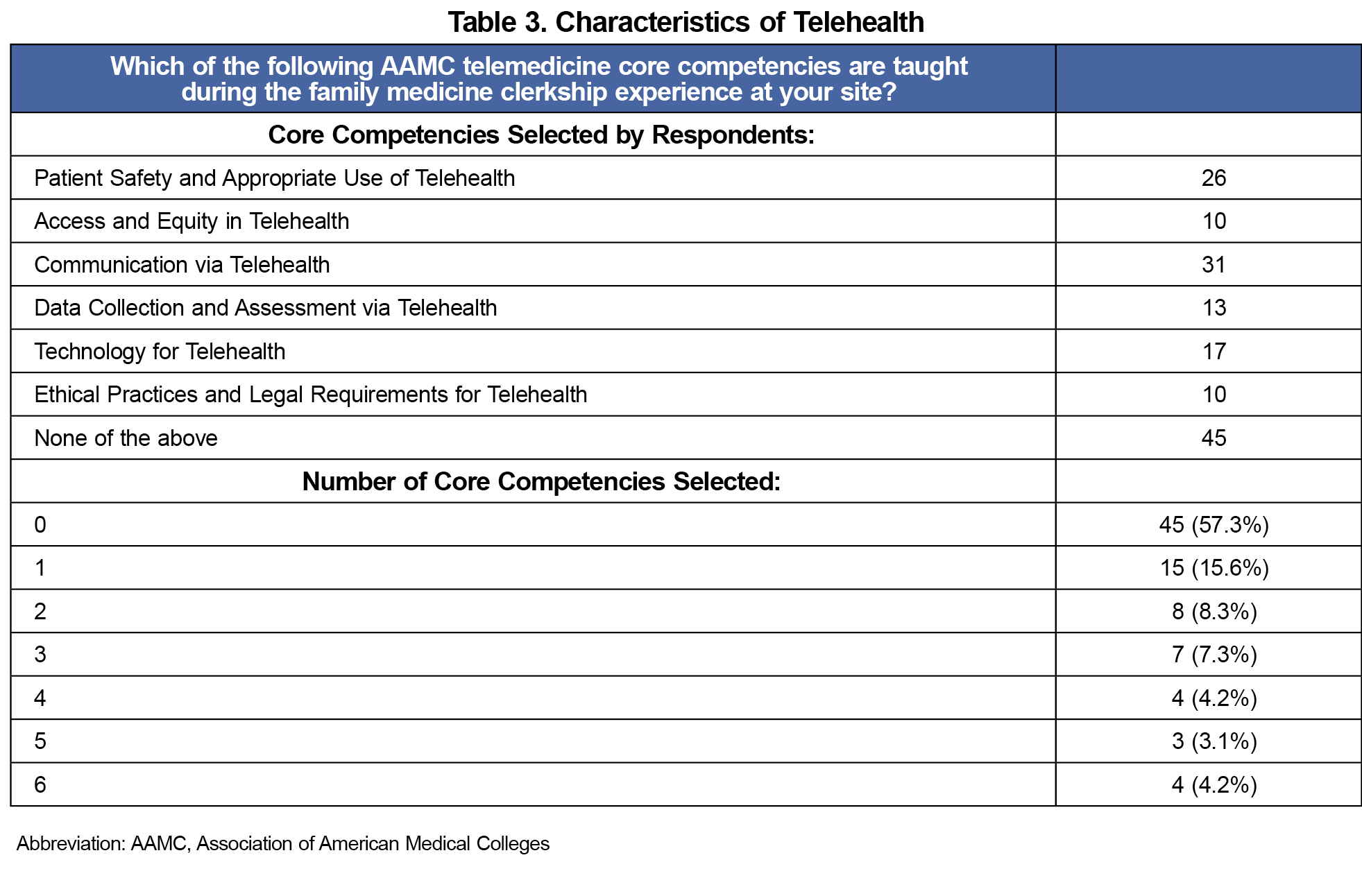

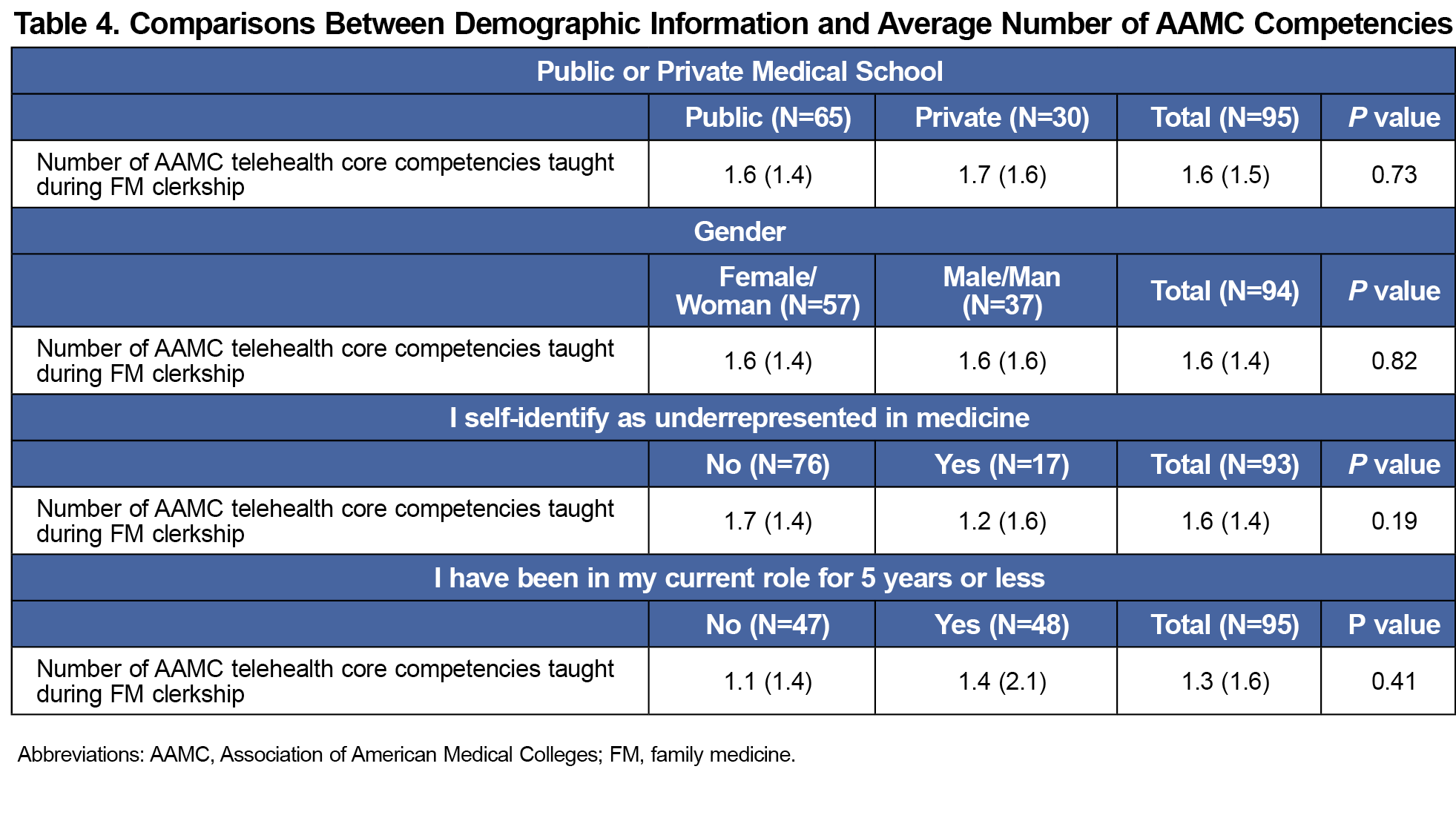

Results: More than half of the responding family medicine clerkships (57.3%) did not teach any of the AAMC telehealth core competencies and only 4.3% taught all six competencies. The three most commonly taught competencies during the clerkship included communication via telehealth (32.2%), patient safety and appropriate use of telehealth (27.1%), and technology for telehealth (17.7%). Most family medicine clerkships (68.0%) identified at least one challenge of the three possible perceived challenges with “limited site resources” as the most reported barrier. There was no significant difference in telemedicine training from CD based on type of medical school (P=.73), gender (P=.82), being a CD for 5 years or less (P=.41), or self-identification as an underrepresented minority in medicine (P=.19).

Conclusions: Of those CDs who responded, many still do not teach the AAMC telehealth core competencies within their family medicine clerkship. The majority reported limited site resources as a barrier to telehealth education.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, clinical rotations were required to adapt to telemedicine. 1-5 In the 2021 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s Education Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors (CDs), 47.1% of responding CDs reported they would likely continue to use telemedicine for teaching in the clerkship, while 17.1% indicated that they were extremely likely to continue to help prepare students for these dynamic health care changes.6A 2022 study found that virtual visits with patient’s own family physician vs an outside physician decreased the likelihood of an emergency department visit in the next 7 days. This indicates that effective virtual care is increased when there is an existing continuity of care relationship that family medicine uniquely provides.7

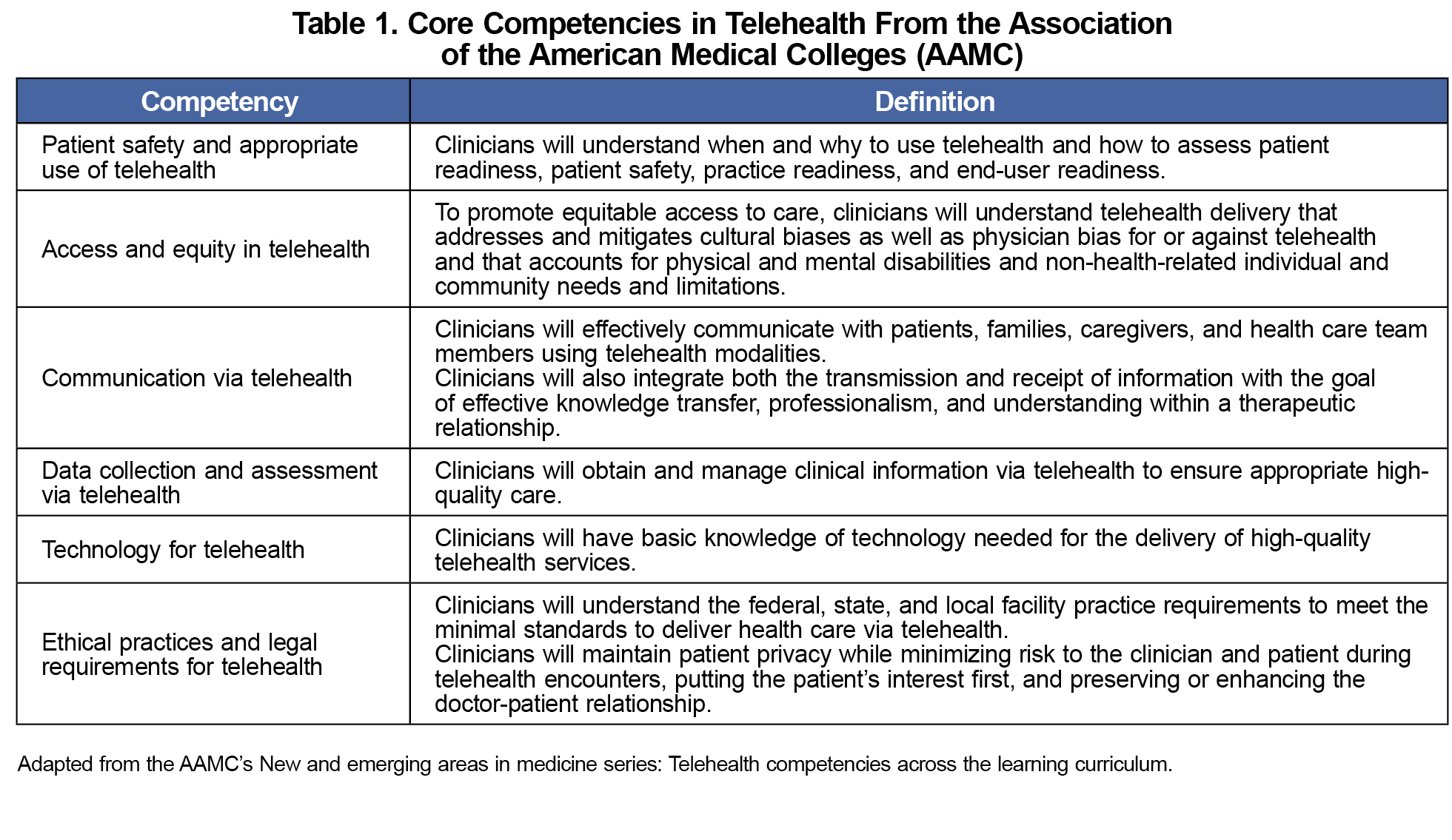

In 2021, the Association of the American Medical Colleges (AAMC) developed core telemedicine competencies to serve as a blueprint when developing curricula, aiming to enhance health care delivery and patient-centered outcomes.8 However, it is unclear if these core competencies are being utilized. Our study aimed to investigate changes after the return to in-person care by examining which AAMC telehealth competencies were taught, any increase in telehealth instruction, and CDs’ perceived challenges to involving medical students in telemedicine as an indication of future impact on medical student education.

Survey

Survey questions were approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board. Data were collected as part of the 2023 CERA survey of family medicine CDs. Surveys were sent via SurveyMonkey (Momentive, Inc, San Mateo, CA) to all family medicine CDs (n=169), 154 in US allopathic medical schools and 15 in Canada. Nonrespondents were sent three weekly reminders about the survey.9

Survey Questions

Demographic data are routinely collected in the annual CERA survey. Questions specific to this project pertained to CDs’ indication of which (if any) of the AAMC telemedicine competencies were being taught during the family medicine clerkship (Table 1). CDs also indicated challenges to involving medical students in telemedicine visits, selecting from limited student knowledge, limited site resources, or patient discomfort involving students in telemedicine visits. Both AAMC telemedicine competency and challenges to involvement questions were written in multiple-choice format with CDs being able to choose multiple answers.

Statistical Analysis

We included surveys with partial data in the analysis and only answered questions were reported in such cases. We analyzed responses using descriptive statistics for demographics, medical school, clerkship, and core competencies. Data were presented as a mean with standard deviation for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. We created a new variable with the number of telemedicine core competencies identified by survey respondents with a range of 0 to 6. A comparison of the average number of telemedicine core competencies by CDs’ demographic variables was completed using a two-sample t test. We set statistical significance at P=.05 and we analyzed data using the statistical software R (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

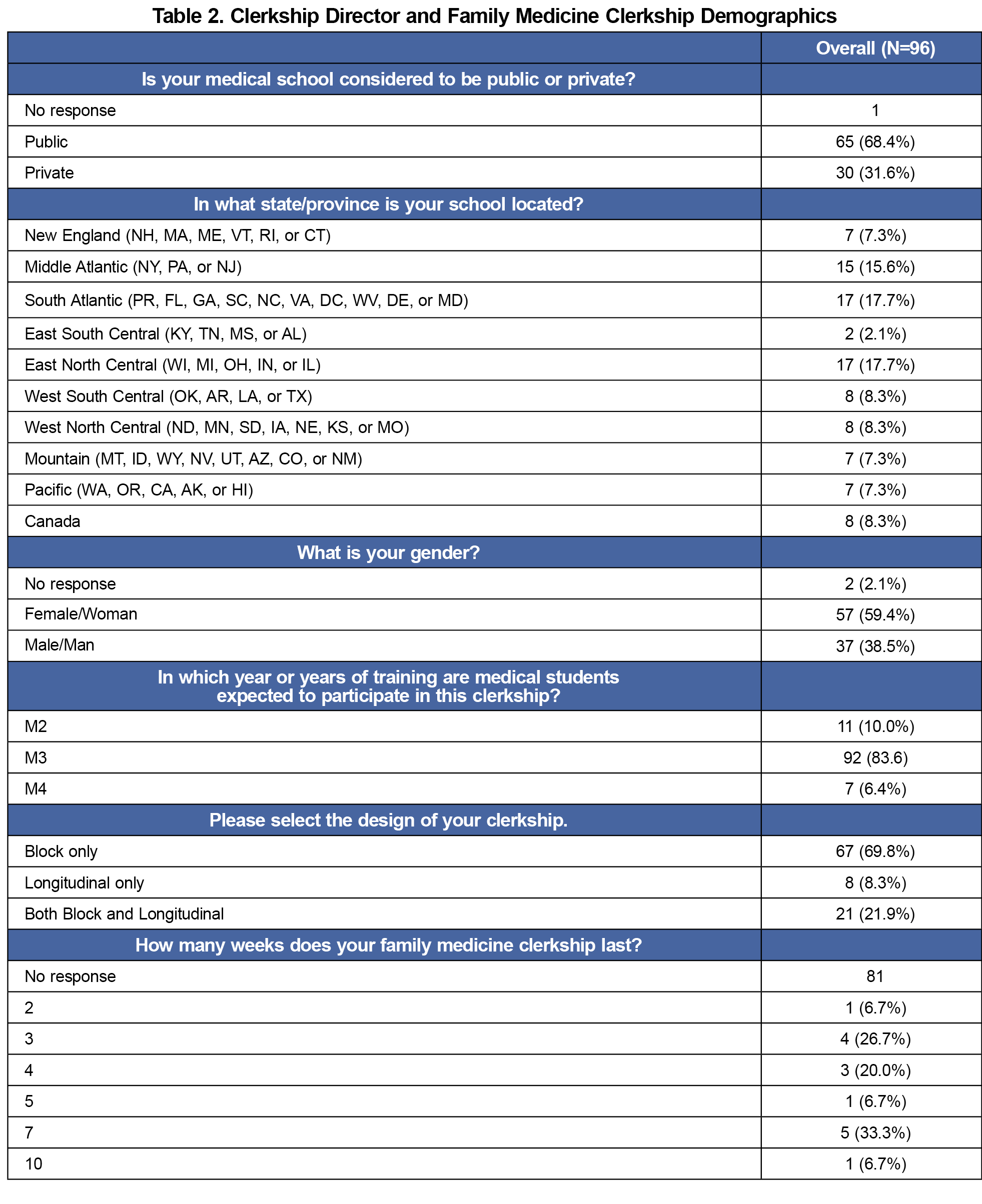

The response rate was 96 of 169 CDs (56.8%) with most family medicine CD respondents being female (59.4%) and working at a public medical school (68.4%, Table 2). CDs were in their current role for 6.5 (5.0) years with 32.3% having 3 years or less experience and 22.9% having 10 years or more experience.

A total of 57.3% of respondents noted that none of the six AAMC telemedicine core competencies were taught during the family medicine clerkship (Table 3). The majority taught either one (15.6%) or two (8.3%) of the six core competencies. The most common competencies taught were communication via telehealth (32.2%), patient safety and appropriate use of telehealth (27.1%), and technology for telehealth (17.7%). There was no significant difference between the average number of AAMC telemedicine competencies taught and CD demographics (Table 4).

Most CDs (67.7%) noted that limited site resources (devices, software, and internet speed) were major barriers to involving medical students in telehealth. Patient discomfort with student participation (25%) and limited student knowledge of telehealth technology (14.6%) were perceived as less significant barriers.

While the 2021 CERA survey data indicated that a majority of family medicine CDs intended to continue to teach telemedicine,6 2022 CERA survey data indicated 41.3% do not teach telemedicine,10 and 2023 CERA Survey data revealed that a majority (57.3%) of family medicine CDs do not teach telemedicine competencies. These findings are most likely due to CDs perception of limited site resources and the lack of awareness of available telemedicine curricula.10 Given that awareness of the Society of Teachers in Family Medicine’s telemedicine curriculum is significantly associated with teaching telemedicine and it is free to access,10 it would be prudent to increase the CDs’ knowledge of available curriculum resources over the next several years through focused educational opportunities at conferences or web-based, independent learning strategies.

In evaluating potential external factors affecting the delivery of telemedicine education in medical training, results showed no significant differences between CD demographic factors and the number of AAMC telemedicine competencies taught. Given no difference was noted, there is a need for continued telemedicine education among all family medicine CD’s, even if the urgency appears lessened following the return of in-person care.

This study is limited in that results may not represent the general population due to the demographics of respondents and the response rate to the survey. In addition, there may be constraints to involving students in telemedicine during their clerkship that is beyond what was listed in the given survey questions. Further studies examining these barriers utilizing the consolidated framework for advancing implementation science is recommended.11

Communication via telehealth, patient safety and appropriate use of telehealth, and technology for telehealth were the three most taught AAMC telemedicine competencies. Though telehealth education has not increased, students could apply this foundational knowledge across the continuum beyond medical school. Further research should be conducted to see whether the number of perceived barriers correlates with the absence of teaching competencies, and how these trends change over time.

References

- Everard KM, Schiel KZ. Changes in family medicine clerkship teaching due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam Med. 2021;53(4):282-284. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.583240

- Jumreornvong O, Yang E, Race J, Appel J. Telemedicine and medical education in the age of COVID-19. Acad Med. 2020;95(12):1838-1843. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003711

- Bhatia RK, Cooley D, Collins PB, Caudle J, Coren J. Transforming a clerkship with telemedicine. J Osteopath Med. 2021;121(1):43-47. doi:10.1515/jom-2020-0131

- Hincapié MA, Gallego JC, Gempeler A, Piñeros JA, Nasner D, Escobar MF. Implementation and Usefulness of Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720980612. doi:10.1177/2150132720980612

- Morgan ZJ, Bazemore AW, Peterson LE, Phillips RL, Dai M. The Disproportionate Impact of Primary Care Disruption and Telehealth Utilization During COVID-19. Ann Fam Med. 2024;22(4):294-300. doi:10.1370/afm.3134

- Everard KM, Schiel KA, Xu E, Kulshreshtha A. Use of Telemedicine in the Family Medicine Clerkship: A CERA Study. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2022;6:25. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2022.105712

- Lapointe-Shaw L, Salahub C, Austin PC, et al. Virtual Visits With Own Family Physician vs Outside Family Physician and Emergency Department Use. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2349452. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.49452

- Association of the American Medical Colleges (AAMC). New and emerging areas in medicine series: Telehealth competencies across the learning curriculum.AAMC; 2021.

- Kost A, Moore MA, Ho T, Biggs R. Protocol for the 2023 CERA Clerkship Director Survey. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2023;7:30. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2023.238868

- Bajra R, Lin S, Theobald M, Antoun J. Telemedicine Competencies in Family Medicine Clerkships: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2023;55(6):405-410. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.242006

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

There are no comments for this article.