Introduction: Residents play an important role in medical education, yet often feel unprepared without formal training. Teaching in the ambulatory setting raises unique challenges such as the difficulty of educating in a limited amount of time. We designed a brief, focused intervention as an initial needs assessment for a residents-as-teachers program in an ambulatory setting to address these concerns.

Methods: A 1-day, 2.5-hour workshop was designed focusing on microskills, providing feedback, and ways to address common barriers in ambulatory teaching. Pre- and postintervention surveys were conducted with both residents and medical students to assess the effects of the workshop on resident teaching in the clinic.

Results: Although postintervention surveys showed increased resident confidence and self-reported teaching behaviors, medical student surveys did not clearly demonstrate an increase in teaching behaviors. Didactic teaching on feedback and microskills with follow-on role playing were seen as the most helpful parts of the intervention.

Conclusions: Self-assessment alone is an inadequate measure of effectiveness of our teaching intervention. While medical student data can help verify resident self-report, future iterations of our intervention should incorporate objective, third-party evaluation of teaching skill implementation.

Residents serve a key role in medical student education, however the art of teaching is often left to the hidden curriculum without formal training. While residents spend up to 20% of their time teaching,1,2 most feel unprepared to teach, a barrier shared by clinical educators in the ambulatory setting.3,4 Resident-as-teacher programs across specialties increase self-reported confidence, enthusiasm, and teaching skills, as well as students’ ratings of resident teaching ability.5-12 As residency programs formalize teaching curricula, ambulatory teaching and feedback are critical topics to include as identified by consensus guidelines.13

While self-assessment is commonly used as an end point in evaluating interventions, it frequently has little correlation to objective measures.14-16 While teaching interventions often result in increased self-reported teaching behaviors, they do not directly correlate with learner outcomes.17

With no formal curriculum established at our program and most teaching occurring in outpatient clinic, we identified an opportunity to improve ambulatory teaching with a focused workshop to improve residents’ self-confidence and teaching skills, gathering data from both residents and medical students to assess workshop efficacy.

A 2.5-hour workshop was integrated into resident didactics attended by all year groups. The workshop included a rotating small group discussion (Gallery Walk) discussing attitudes toward teaching, pocket references, and lectures on utilizing microskills and giving effective feedback.18-21 Residents then practiced specific microskills and elements of feedback through role play. Finally, barriers to teaching in the ambulatory setting and potential solutions were discussed.

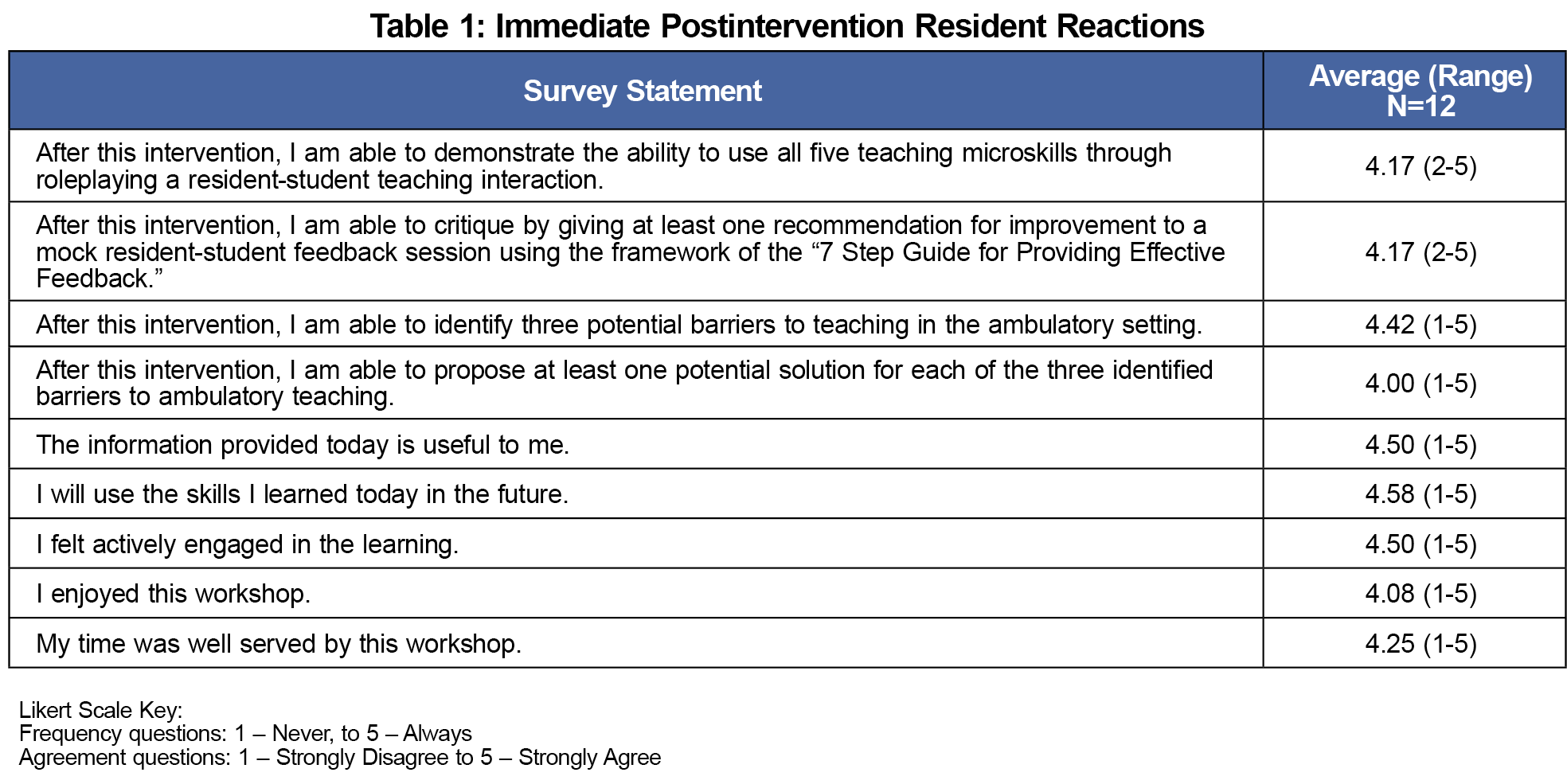

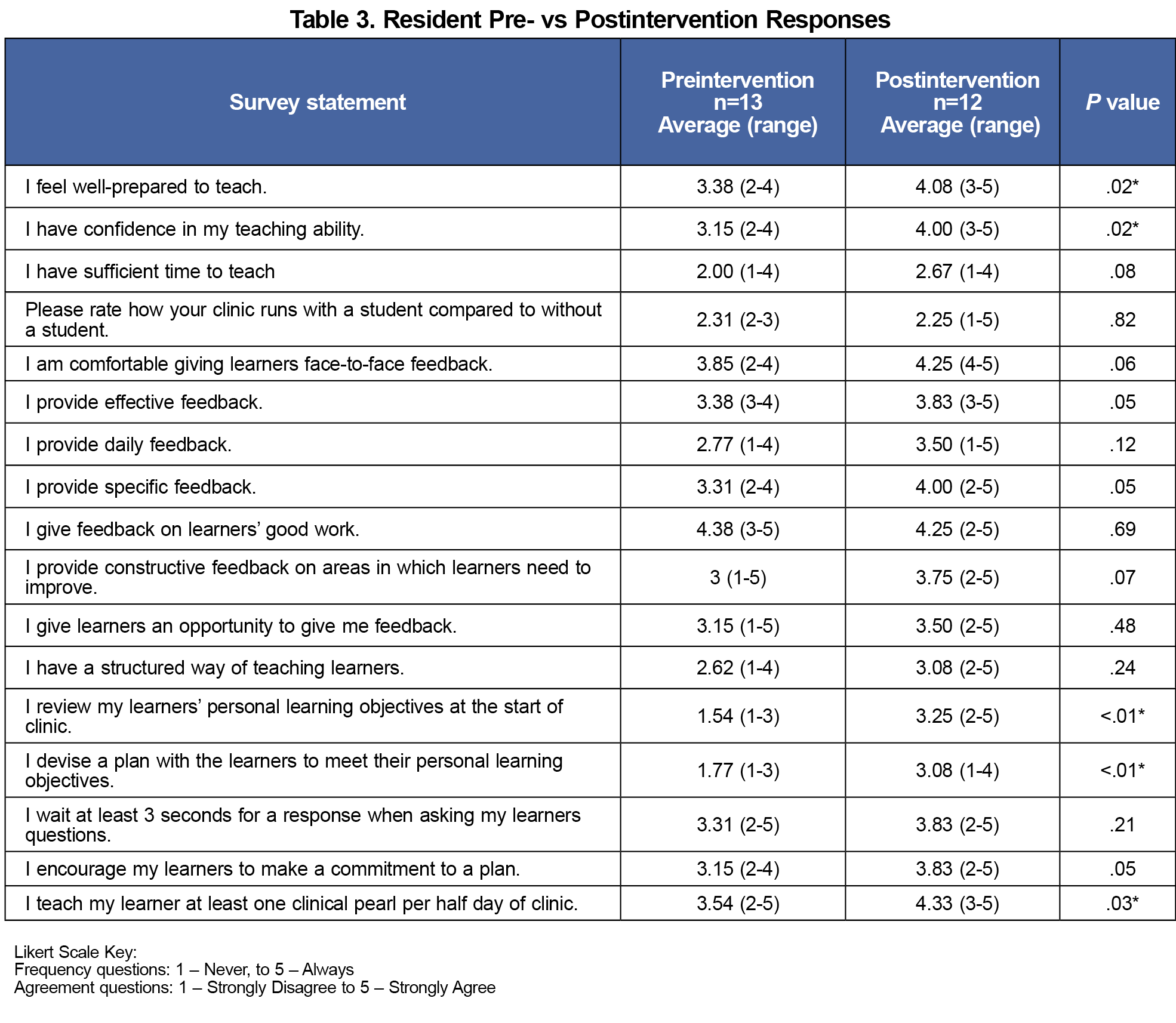

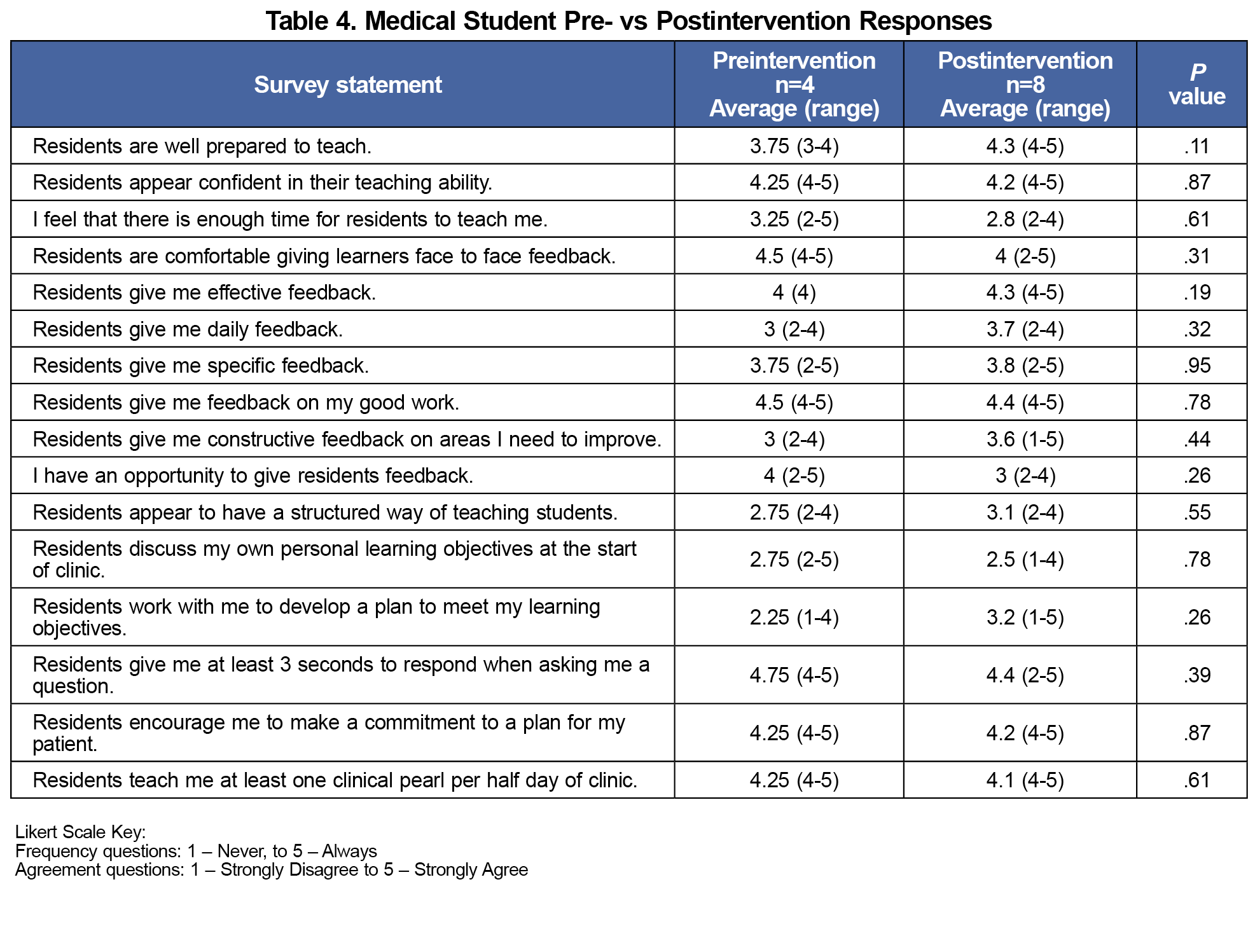

Surveys utilized a 5-point Likert scale to evaluate outcomes on various levels of the New World Kirkpatrick Model of evaluation.22 An immediate postintervention survey captured resident reactions to the workshop (Kirkpatrick level 1). Follow-on resident surveys evaluated confidence and implementation of teaching behavior in clinic (Kirkpatrick level 2 and self-reported level 3). Medical student surveys assessed changes in teaching behaviors from the student perspective (Kirkpatrick level 3). Resident preintervention data were collected just prior to the workshop and postintervention data were collected 3 months after. Anonymous end-of-rotation preintervention surveys were provided to students rotating through the Family Medicine Residency at Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton for 3 months prior to the workshop, while postintervention surveys were collected for 5 months following the workshop. Due to the nature of the clerkship schedule, there was no overlap between medical students in the preintervention group and those in the postintervention group. Likewise, due to away rotations at other local hospitals, some residents in the postintervention group may have been different than those in the preintervention group.

We converted Likert scale results into numerical values and compared via two-sample t test with unequal variance. This project was determined to be exempt from review by the Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton Clinical Investigation Program, under exemption #2. Full intervention materials are available on the STFM Resource Library.23

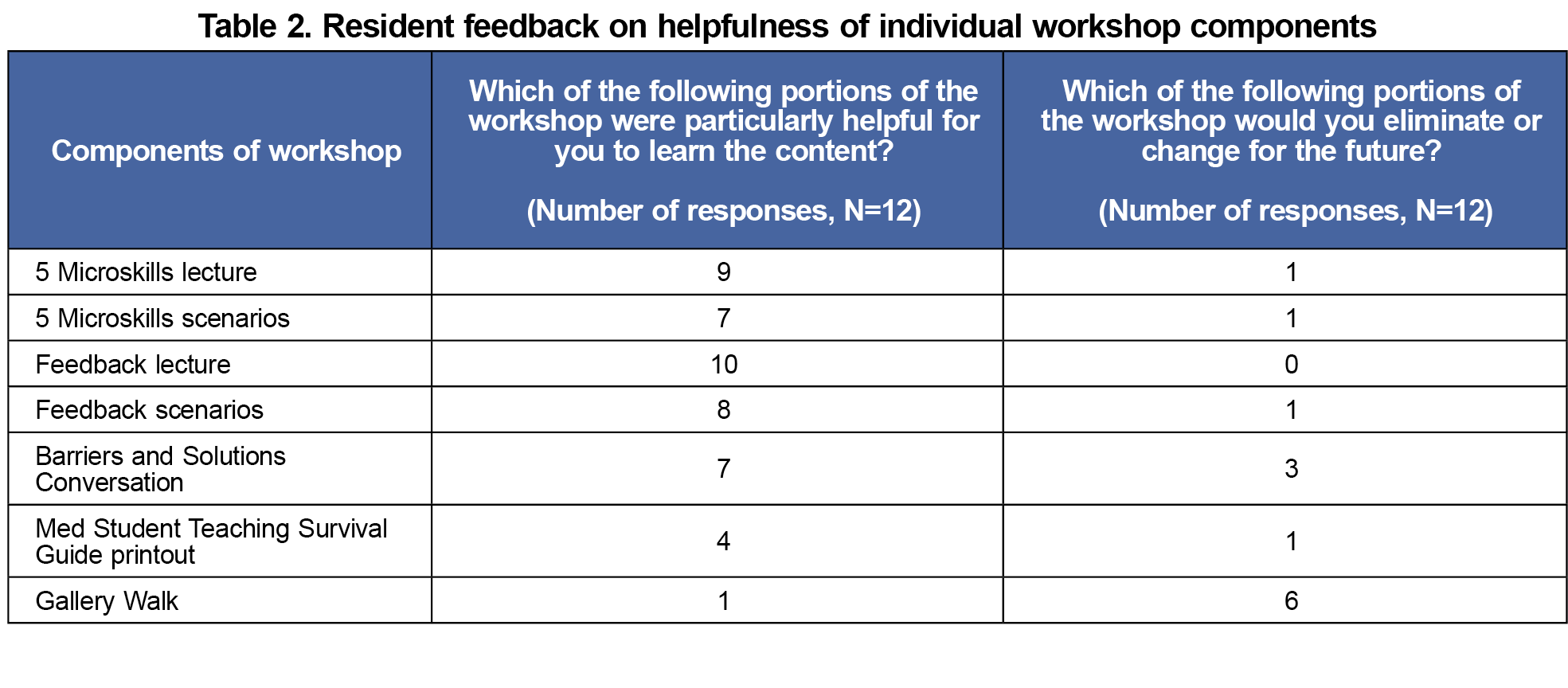

There were 13 preintervention and 12 postintervention resident responses, as well as four pre-intervention and eight postintervention student responses. Immediate postworkshop reactions showed residents felt the content was useful, particularly lectures and roleplay scenarios (Tables 1 and 2). Resident postintervention surveys showed significant increases in self-reported preparedness, confidence, and utilization of microskills. Self-reported use of effective feedback skills increased but was not significant (Table 3). Student responses reflected improved resident preparedness to teach and improved frequency and quality of feedback but did not reflect increases in other teaching behaviors (Table 4).

Our intervention had positive impacts at Kirkpatrick levels 1 and 2 with good initial reaction and increased resident self-confidence but failed to translate into significantly changed behavior in student responses. Role-play scenarios during the workshop appeared to increase preparedness and confidence, suggesting this would be helpful in future iterations. Conversely, the initial small group discussion was not perceived as helpful and should be changed in future iterations.

Several insights were only made possible through triangulating resident self-report with medical student responses, emphasizing the importance of moving beyond self-report alone in evaluating the efficacy of teaching programs. While residents self-reported increases in teaching behaviors, students did not recognize this change. Among teaching microskills, students only noted increased learning plan development. While other microskills such as pausing to allow time for response may not be recognized by students, establishing goals before clinic may have been apparent. Although residents reported an increase in giving learners the opportunity for feedback, students disagreed, again raising questions on the correlation between self-reporting and actual behavior. Possible explanations include that residents learned the importance of feedback but failed to implement it regularly, or medical students lacked recognition of feedback when given. The data collected do not allow further examination of the discrepancy, revealing a gap in a survey-only collection model.

Our findings are consistent with a growing trend in medical education literature recognizing the inadequacies of self-reporting and use of student evaluations as the only metrics for curricula efficacy, instead shifting toward more objective evaluation of teaching efficacy from multiple sources.24-26 While we attempted to mitigate the inadequacies of self-report with student surveys, there are other limitations, such as asking for aggregated assessments on resident teaching at end of rotation instead of individual teaching experiences. Use of survey data alone does not explain why there are discrepancies between resident self-report and learner responses. Future iterations should include direct observation of teaching from peers or faculty who can provide feedback on teaching technique. While this is more time-consuming, we believe it could provide a more complete assessment on intervention effectiveness.

The data from our study are limited by the small number of participants and may be underpowered to detect significant changes or reach actionable quantitative conclusions. In addition, having different students involved in the pre- and postintervention surveys makes it challenging to determine if changes were due to the intervention or from personal student factors. Overall, our use of learner data and resident input emphasizes the risks of relying on self-assessment data and demonstrates the importance of capturing data from learners and teachers simultaneously to improve the experiences of both groups. Future iterations should further work on translating knowledge into learner-focused outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr Paul Crawford for his advice regarding study design, as well as Dr Wayne Altman for use of portions of his handout “Teaching Well Without Falling Behind.”

Presentations: Uniformed Service Academy of Family Physicians Annual Meeting 2024

Conflict Disclosure: The views expressed in this article reflect the results of research conducted by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, nor the United States Government.

References

- Mann KV, Sutton E, Frank B. Twelve tips for preparing residents as teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29(4):301-306. doi:10.1080/01421590701477431

- Busari JO, Prince KJ, Scherpbier AJ, Van Der Vleuten CP, Essed GG. How residents perceive their teaching role in the clinical setting: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2002;24(1):57-61. doi:10.1080/00034980120103496

- Kobritz M, Demyan L, Hoffman H, Bolognese A, Kalyon B, Patel V. “Residents as Teachers” workshops designed by surgery residents for surgery residents. J Surg Res. 2022;270:187-194. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2021.09.003

- Bowen JL, Irby DM. Assessing quality and costs of education in the ambulatory setting: a review of the literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(7):621-680. doi:10.1097/00001888-200207000-00006

- McKinley SK, Cassidy DJ, Sell NM, et al. A qualitative study of the perceived value of participation in a new Department of Surgery Research Residents as teachers program. Am J Surg. 2020;220(5):1194-1200. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.056

- Aiyer M, Woods G, Lombard G, Meyer L, Vanka A. Change in residents’ perceptions of teaching: following a one day “Residents as Teachers” (RasT) workshop. South Med J. 2008;101(5):495-502. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31816c00e4

- Anderson MJ, Ofshteyn A, Miller M, Ammori J, Steinhagen E. “Residents as teachers” workshop improves knowledge, confidence, and feedback skills for general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):757-764. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.01.010

- Berger JS, Daneshpayeh N, Sherman M, et al. Anesthesiology residents-as-teachers program: a pilot study. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):525-528. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00300.1

- Gaba ND, Blatt B, Macri CJ, Greenberg L. Improving teaching skills in obstetrics and gynecology residents: evaluation of a residents-as-teachers program. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;196(1):87. e1-87. e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.037

- Morrison EH, Rucker L, Boker JR, et al. The effect of a 13-hour curriculum to improve residents’ teaching skills: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):257-263. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00005

- Ratan BM, Johnson GJ, Williams AC, Greely JT, Kilpatrick CC. Enhancing the teaching environment: 3-year follow-up of a resident-led residents-as-teachers program. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(4):569-575. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-01167.1

- Wamsley MA, Julian KA, Wipf JE. A literature review of “resident-as-teacher” curricula: do teaching courses make a difference? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5 Pt 2):574-581. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30116.x

- McKeon BA, Ricciotti HA, Sandora TJ, et al. A consensus guideline to support resident-as-teacher programs and enhance the culture of teaching and learning. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(3):313-318. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00612.1

- Bernardo MO, Cecílio-Fernandes D, Costa P, Quince TA, Costa MJ, Carvalho-Filho MA. Physicians’ self-assessed empathy levels do not correlate with patients’ assessments. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0198488. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198488

- Graves L, Lalla L, Young M. Evaluation of perceived and actual competency in a family medicine objective structured clinical examination. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(4):e238-e243.

- Brinkman DJ, Tichelaar J, van Agtmael MA, de Vries TP, Richir MC. Self-reported confidence in prescribing skills correlates poorly with assessed competence in fourth-year medical students. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55(7):825-830. doi:10.1002/jcph.474

- Hill AG, Srinivasa S, Hawken SJ, et al. Impact of a resident-as-teacher workshop on teaching behavior of interns and learning outcomes of medical students. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):34-41. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00062.1

- Gordon K, Meyer B, Irby D. The One Minute Preceptor: five microskills for clinical teaching.University of Washington; 1996.

- Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5(4):419-424.

- Chandler D, Snydman L, Rencic J. Implementing direct observation of resident teaching during work rounds at your institution. Acad Int Med Insight. 2009;7(4):14-15.

- Snydman L, Chandler D, Rencic J, Sung Y-C. Peer observation and feedback of resident teaching. Clin Teach. 2013;10(1):9-14. doi:10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00591.x

- Kirkpatrick JD, Kirkpatrick WK. Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation.Association for Talent Development; 2016.

- Zhang G, Crispell R, Koch J. Outpatient Clinic Resident as Teacher Workshop. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Resource Library. Accessed June 27, 2024. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/outpatient-clinic-resident-as-teach?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

- Morley CP. Moving on from self-assessment. PRiMER. 2024;8:5. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2024.624901

- Constantinou C, Wijnen-Meijer M. Student evaluations of teaching and the development of a comprehensive measure of teaching effectiveness for medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):113. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03148-6

- Ragsdale JW, Berry A, Gibson JW, Herber-Valdez CR, Germain LJ, Engle DL; Representing the Program Evaluation Special Interest Group of the Southern Group on Educational Affairs (SGEA) within the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Evaluating the effectiveness of undergraduate clinical education programs. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1757883. doi:10.1080/10872981.2020.1757883

There are no comments for this article.