Introduction: While guidelines exist for physicians to identify and respond to patients experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV), no studies describe physician practices of making mandated reports, advising patients about confidentiality limitations, or conducting homicide risk assessment. This pilot study aimed to explore current physician responses to patient disclosure of experiencing IPV.

Methods: We sent interview invitations from March to August 2022 to 11 US national medical societies and 118 state chapters for family medicine, general internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, emergency medicine, and plastic surgery. We conducted semi-structured qualitative online interviews that were recorded and transcribed. We conducted a thematic analysis to determine codes and themes.

Results: Participants consisted of ten female and three male physicians with a median of 16 years in practice. Analysis revealed two themes based on self-reported knowledge and actions: (1) limited knowledge and use of mandatory reporting and risk assessment, and (2) reliance on team members due to limited protocol awareness and time. Most participants did not recall reporting requirements, and few physicians described reporting IPV to law enforcement, advising patients of confidentiality limitations, or conducting risk assessments. As a result of time barriers and limited expertise about protocols and resources, participants relied on social work and nursing team members to respond to IPV.

Conclusions: Physicians in this sample describe limited knowledge and use of mandatory reporting and safety assessment. These limitations can be further investigated in larger studies to determine the need for trainings that include reporting requirements and for developing IPV response protocols.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a critical public health issue, and health care guidelines emphasize ongoing training, understanding legal reporting requirements, conducting safety assessments, awareness of protocols, and referrals to community resources.1-5 The World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines emphasize communicating confidentiality limitations, shared decision-making, and homicide risk assessment following IPV disclosures.6-7 Nearly all US states require healthcare providers to report to law enforcement when patients have acute injuries due to violence, despite medical organization recommendations against mandated reporting.8,9

Despite guidelines, physician knowledge of IPV intervention protocols, including mandatory reporting, safety assessment, and warm referrals to local services, remains limited.8, 10-13 Only two studies from the 1990s describe US physician knowledge of mandatory reporting, demonstrating physician awareness ranging from 29-86%.14-15 Prior studies of physician knowledge of their worksite’s IPV protocol ranged from 0%-24%.16-17 Regarding intervention, one study, including only four physicians, described warm referrals to on-site social work, and a survey of 400 physicians reported referral to shelters (79%) and counseling (88%).16,18 No studies describe physician practices of mandatory reporting, communication of confidentiality limitations, or risk assessment. This study explores physician responses to patient IPV disclosures, focusing on mandatory reporting to law enforcement based on state laws and institutional protocols, homicide risk assessment, clinical protocols, and collaboration with healthcare team members for community referrals.

We recruited US family medicine, general internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, emergency medicine, and plastic surgery physicians. Participants were members of eleven national medical societies.19 Recruitment occurred via digital newsletters and interested participants completed an online form to provide contact information. Participants provided informed consent after receiving information describing study objectives, right to withdraw data, audio recordings for transcription, and voluntary participation with no compensation.

From March to August 2022, the first author conducted 30-60-minute semi-structured interviews via Zoom.19 The interview audio was recorded and transcribed. The lead author developed codes and a codebook using thematic analysis and the WHO IPV screening guidelines.20-22 Codes were reviewed and revised with coauthors who have backgrounds in IPV research and education (authors V.S., M.L., A.L.), qualitative research (V.S., A.L., M.L.) and family medicine (V.S.). To ensure coding agreement, one coauthor (A.L.) reviewed and revised the application of codes to one transcript. Data saturation was achieved after 13 interviews. The Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Berkeley approved this study.

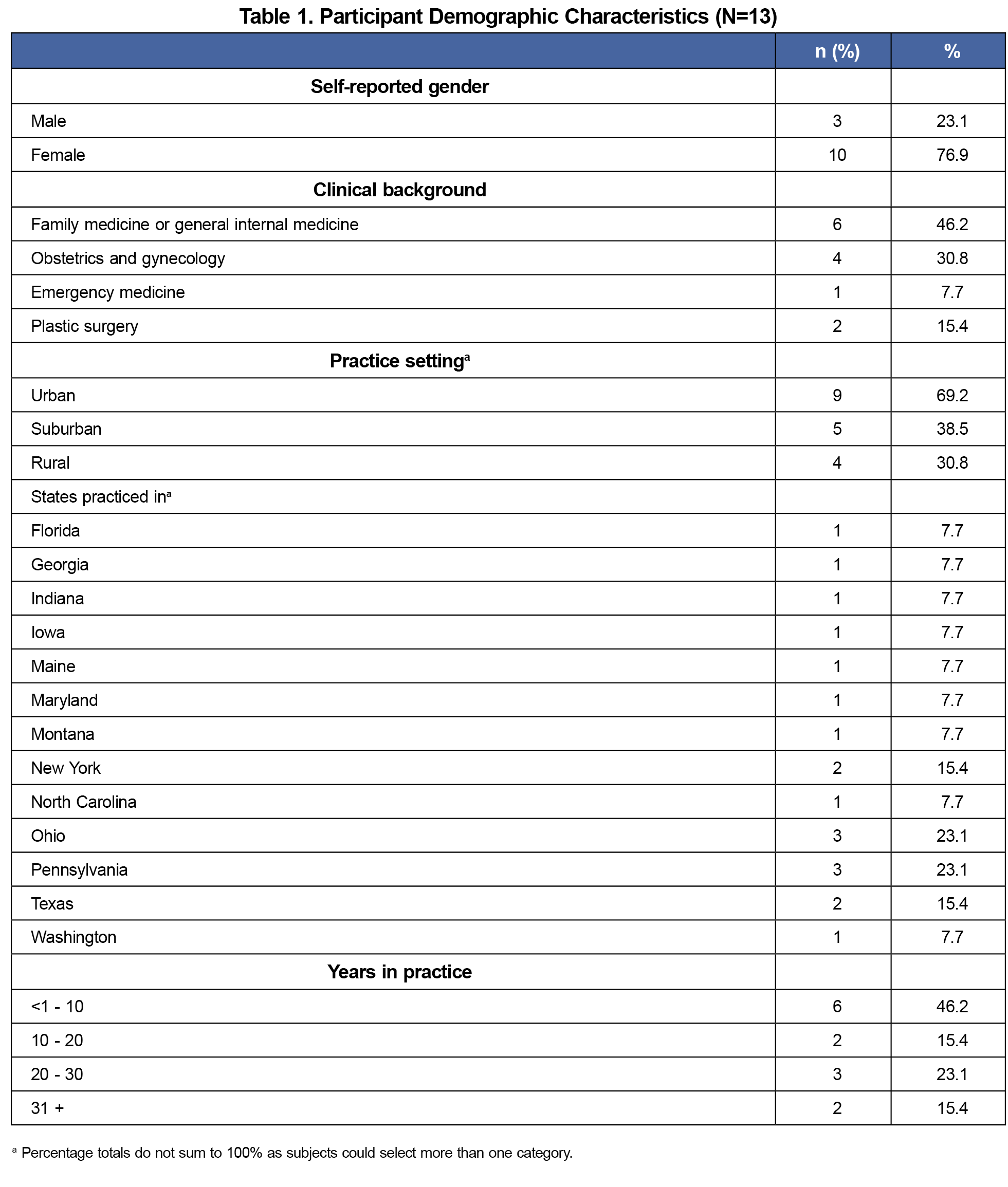

The study included 13 physicians (10 female, 3 male; median 16 years in practice; Table 1). All had experience caring for patients experiencing IPV. Two primary themes emerged from analyses.

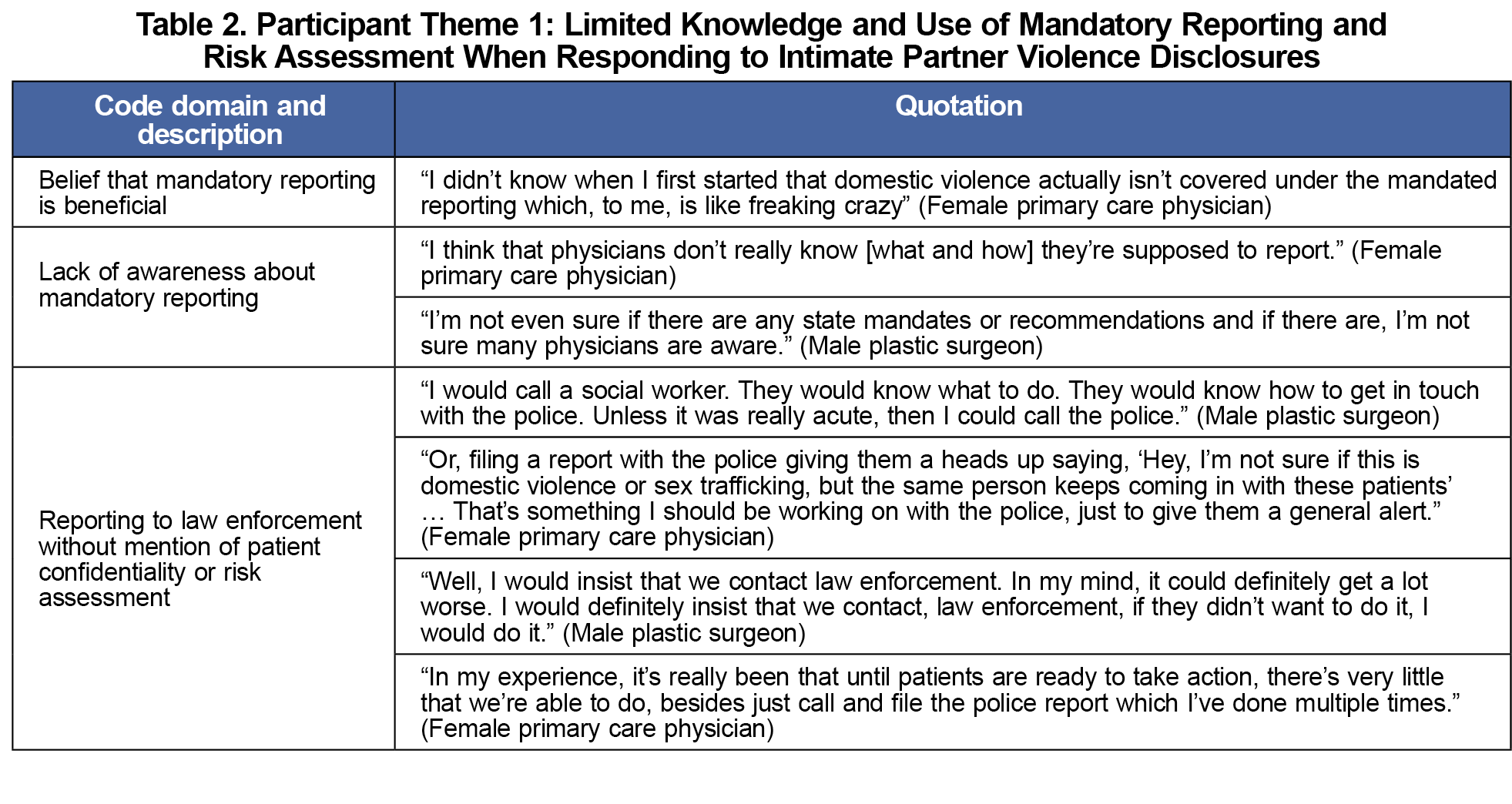

The first theme is limited knowledge and use of mandatory reporting and risk assessment (Table 2). All respondents practiced in states that mandate reporting.8 However, most participants were unaware of their state reporting requirement and no patients were aware of institutional reporting requirements. Only one emergency medicine physician recognized the state law, potentially due to experiences with acute injuries. There was confusion about navigating the judicial system and law enforcement relationships. Some physicians supported mandatory reporting, although none reported making a mandated report. However, two physicians explained that they would hypothetically report to law enforcement if their patient experienced IPV, and two others described experiences contacting law enforcement, but none described communicating confidentiality limitations. No physicians reported using evidence-based homicide risk assessment tools, such as the Danger Assessment.23

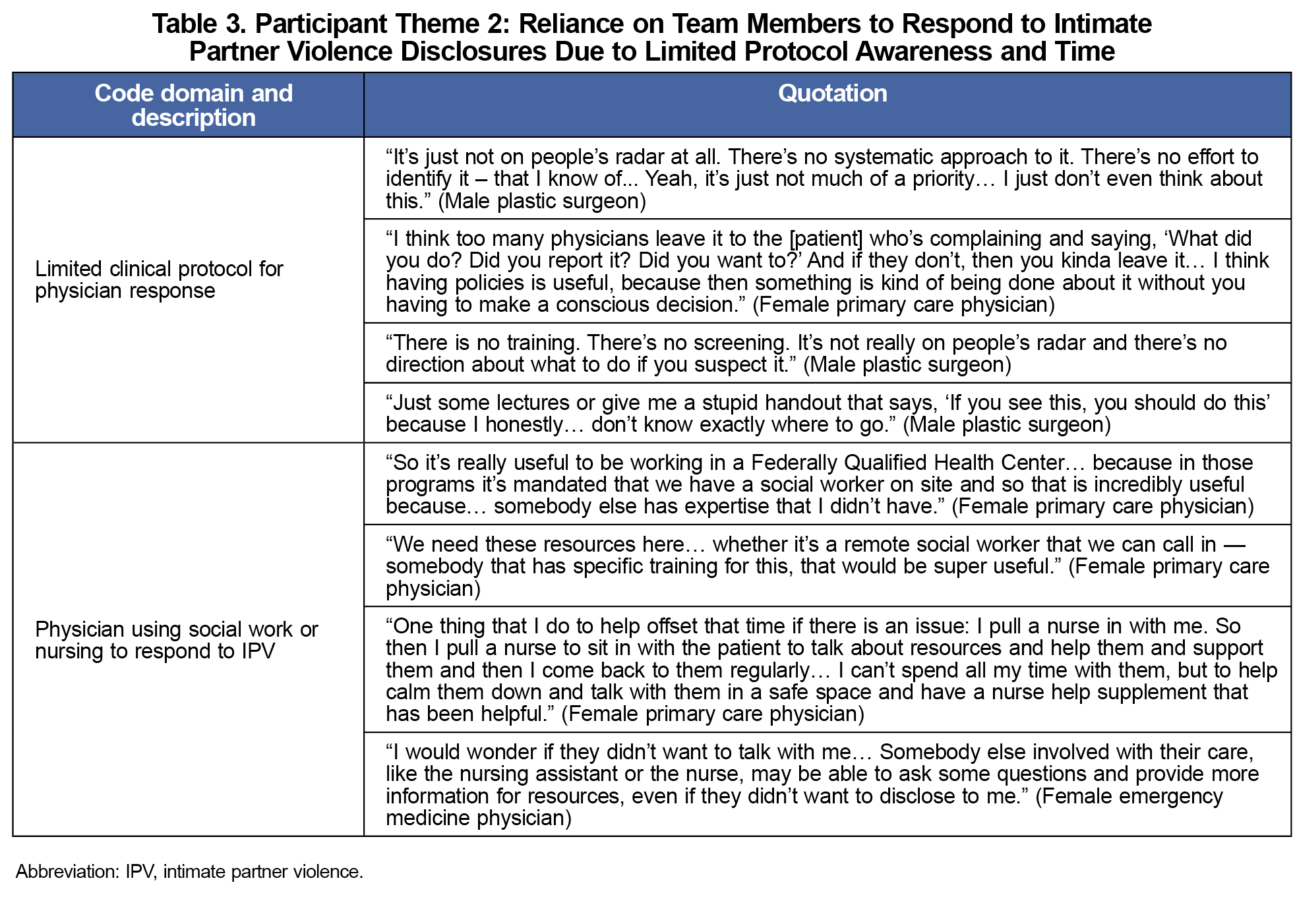

The second theme is reliance on team members due to limited protocol awareness and time (Table 3). All participants expressed frustration over the lack of guidance for responding to IPV, including an absence of intervention protocols at their institutions. Several participants described that protocol implementation may be limited because IPV is not a clinical priority. Most participants felt that time barriers and limited expertise led to relying on social work and nursing staff to respond to IPV disclosures, acknowledging their greater expertise and availability.

This pilot study highlights themes in physician knowledge and practice behaviors regarding IPV response. Clinicians in our sample had extensive clinical experience, yet were unaware of or did not use mandatory reporting, homicide risk assessment, or clinical protocols to respond to IPV disclosures. The absence of protocols reported by participants underscores a need to investigate the prevalence of IPV intervention guidelines for physicians at clinical sites.

Mandatory reporting to law enforcement without providing confidentiality limitations, nor performing homicide risk assessment or safety planning can increase risk for IPV survivors. Given how some physicians in our sample supported reporting to law enforcement, physician education about confidentiality limitations, safety planning, safety risks associated with reporting, and advocacy for legislative changes is essential.5,24

Reliance on social workers and nursing staff in our sample enabled physicians to offer warm referrals and expert support, regardless of knowledge gaps and time barriers. Support from a multidisciplinary team may enhance physicians’ willingness to identify IPV by offering expertise, while considering time and knowledge constraints.

This study has important limitations. As a qualitative study, it captures in-depth experiences that may not represent the broader physician community. We obtained a small purposeful convenience sample of clinicians that was likely biased toward interest in IPV. However, selection bias appears minimal, as many participants reported limited knowledge of steps in IPV response. Our participant’s limited knowledge was surprising considering the sample was likely interested in IPV. Our sample had diversity of clinical disciplines but not gender as our participants were primarily women with an interest in IPV. We also did not assess differences between family medicine and general internal medicine, given a lack of recording types of primary care physicians. While interview requests were sent to multiple medical organizations, most did not permit dissemination requests. Although the lead author was responsible for developing and applying codes to transcripts, all authors reviewed and revised codes, codebook, and themes.

Although this pilot study is limited by its qualitative nature and small sample size, the findings offer valuable insights that can inform larger, quantitative needs based-assessment of training and protocol development that could influence physician behaviors in practice, rather than solely delivering educational interventions, to ensure safe, patient-centered care for IPV survivors.

Acknowledgments

Prior presentation: This study was presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine 2024 Annual Spring Conference, May 3-7, 2024, in Los Angeles, California.

References

- Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; November 2018. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/60893

- Sohal AH, Feder G, Barbosa E, et al. Improving the healthcare response to domestic violence and abuse in primary care: protocol for a mixed method evaluation of the implementation of a complex intervention. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):971. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5865-z

- Sohal AH, Feder G, Boomla K, et al. Improving the healthcare response to domestic violence and abuse in UK primary care: interrupted time series evaluation of a system-level training and support programme. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):48. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-1506-3

- McCaw B, Berman WH, Syme SL, Hunkeler EF. Beyond screening for domestic violence: a systems model approach in a managed care setting. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(3):170-176. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00347-6

- Preventing, Identifying & Treating Violence & Abuse. American Medical Association. Accessed November 15, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/preventing-identifying-treating-violence-abuse

- Singh V, Petersen K, Singh SR. Intimate partner violence victimization: identification and response in primary care. Prim Care. 2014;41(2):261-281. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2014.02.005

- Caring for Women Subjected to Violence: A WHO Curriculum for Training Health-Care Providers.Revised Edition 2021. World Health Organization; 2021. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039803

- Lizdas KC, O’Flaherty A, Durborow N, Marjavi A. Compendium of State and U.S. Territory Statutes and Policies on Domestic Violence and Health Care.Futures Without Violence; 2019. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://ipvhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Compendium-4th-Edition-2019-Final-small-file.pdf

- Mandatory Reporting of Domestic Violence to Law Enforcement by Health Care Providers: A Guide for Advocates Working to Respond to or Amend Reporting Laws Related to Domestic Violence. Futures Without Violence; 2019

- Messing JT, Campbell JC, Snider C. Validation and adaptation of the danger assessment-5: A brief intimate partner violence risk assessment. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(12):3220-3230. doi:10.1111/jan.13459

- Ramsay J, Rutterford C, Gregory A, et al. Domestic violence: knowledge, attitudes, and clinical practice of selected UK primary healthcare clinicians. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(602):e647-e655. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X654623

- Cann K, Withnell S, Shakespeare J, Doll H, Thomas J. Domestic violence: a comparative survey of levels of detection, knowledge, and attitudes in healthcare workers. Public Health. 2001;115(2):89-95. doi:10.1016/S0033-3506(01)00425-5

- Ragavan MI, Murray A. Supporting intimate partner violence survivors and their children in pediatric healthcare settings. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2023;70(6):1069-1086. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2023.06.016

- Rodriguez MA, McLoughlin E, Bauer HM, Paredes V, Grumbach K. Mandatory reporting of intimate partner violence to police: views of physicians in California. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(4):575-578. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.4.575

- Henry SL, Roth M, Gleis LH. Domestic violence--the medical community’s legal duty. J Ky Med Assoc. 1992;90(4):162-169.

- Alvarez C, Debnam K, Clough A, Alexander K, Glass NE. Responding to intimate partner violence: healthcare providers’ current practices and views on integrating a safety decision aid into primary care settings. Res Nurs Health. 2018;41(2):145-155. doi:10.1002/nur.21853

- McGrath ME, Bettacchi A, Duffy SJ, Peipert JF, Becker BM, St Angelo L. Violence against women: provider barriers to intervention in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(4):297-300. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03552.x

- Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E, Grumbach K. Screening and intervention for intimate partner abuse: practices and attitudes of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1999;282(5):468-474. doi:10.1001/jama.282.5.468

- Chau C, Lesser MNR. Lutnick A. Interview guide: physician responses to IPV. 2023. STFM Resource Library. Accessed August 28, 2024. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/interview-guide-physician-response?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

- Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):846-854. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

- Addressing Violence against Women in Pre-Service Health Training: Integrating Content from the Caring for Women Subjected to Violence Curriculum. World Health Organization; 2023. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240064638

- Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237-246. doi:10.1177/1098214005283748

- Campbell JC, Webster DW, Glass N. The danger assessment: validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(4):653-674. doi:10.1177/0886260508317180

- The Health System Response to Violence against Women in the WHO European Region: A Baseline Assessment. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2019. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2019-3780-43539-61155

There are no comments for this article.