Introduction: The current sociopolitical landscape surrounding lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) communities involves discrimination in multiple areas of life. Medical education on LGBTQ+ health is often variable and incomplete. As part of a comprehensive evaluation of LGBTQ+ health in our curriculum, we explored student experiences learning about LGBTQ+ health during medical school, including the impact of the sociopolitical landscape.

Methods: We conducted focus groups of medical students at a single Midwest institution in March 2024. All medical students were invited to participate. We analyzed the data using an inductive systematic hierarchical thematic qualitative analysis approach to describe key themes.

Results: Eighteen medical students participated in three focus groups. Analysis demonstrated 13 key themes across three domains: (1) elements that impacted student learning (six key themes, 28 subthemes); (2) aspects participants would change regarding how LGBTQ+ health is taught (four key themes, 11 subthemes); and (3) ways the sociopolitical landscape has impacted their education or anticipated career trajectory (three key themes). Most participants reported that the current sociopolitical landscape surrounding LGBTQ+ communities has impacted their education or anticipated career trajectory.

Conclusion: Medical students described positive, negative, and neutral factors that impacted their education on LGBTQ+ health in the formal and hidden curriculum. Students described insufficient learning opportunities in preclinical and clinical settings with various factors in the hidden curriculum impacting their learning. The current sociopolitical landscape surrounding LGBTQ+ communities may influence where medical students pursue future training and careers due to learning goals or identity.

About 7.6% of the population in the United States identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer (LGBTQ+).1 LGBTQ+ communities experience health disparities,2-5 report negative experiences with healthcare providers,6-8 and may not seek care due to fear of discrimination.7,9 Access is further threatened by state legislation that restricts access to care for members of LGBTQ+ communities, especially those who are transgender and gender diverse (TGD).10-12

Beyond healthcare, the current sociopolitical landscape in the US threatens LGBTQ+ individuals in many aspects of life. Discrimination against LGBTQ+ people exists at both the interpersonal and institutional levels and includes experiences of harassment and microaggressions across many contexts, including in housing, employment, educational, and legal settings.7,8,13,14 Discrimination has been found to exacerbate mental health challenges for LGBTQ+ communities.8,15 Taken altogether, LGBTQ+ people face inequities and injustices, including related to health, emphasizing the importance of adequate physician preparation.

Despite the demonstrated need, medical education on LGBTQ+ health is variable and often incomplete.16,17 Medical students have gaps in knowledge and preparedness to care for these populations, especially TGD patients.16 Two studies to date have demonstrated that state legislation limiting access to care for TGD individuals impacts medical student applications and plans for residency.18,19 Further research is needed to elucidate how this legislation and the broader sociopolitical landscape impact medical training.

Recent evaluations at our institution identified gaps in preclinical LGBTQ+ health education through a systematic content evaluation20 and medical student surveys.21 Our study explores medical student experiences learning about LGBTQ+ health, including educational materials used, factors that impacted their learning, aspects of LGBTQ+ health education they would change, and the ways, if at all, the sociopolitical environment surrounding LGBTQ+ communities impacts their education or anticipated career trajectory.

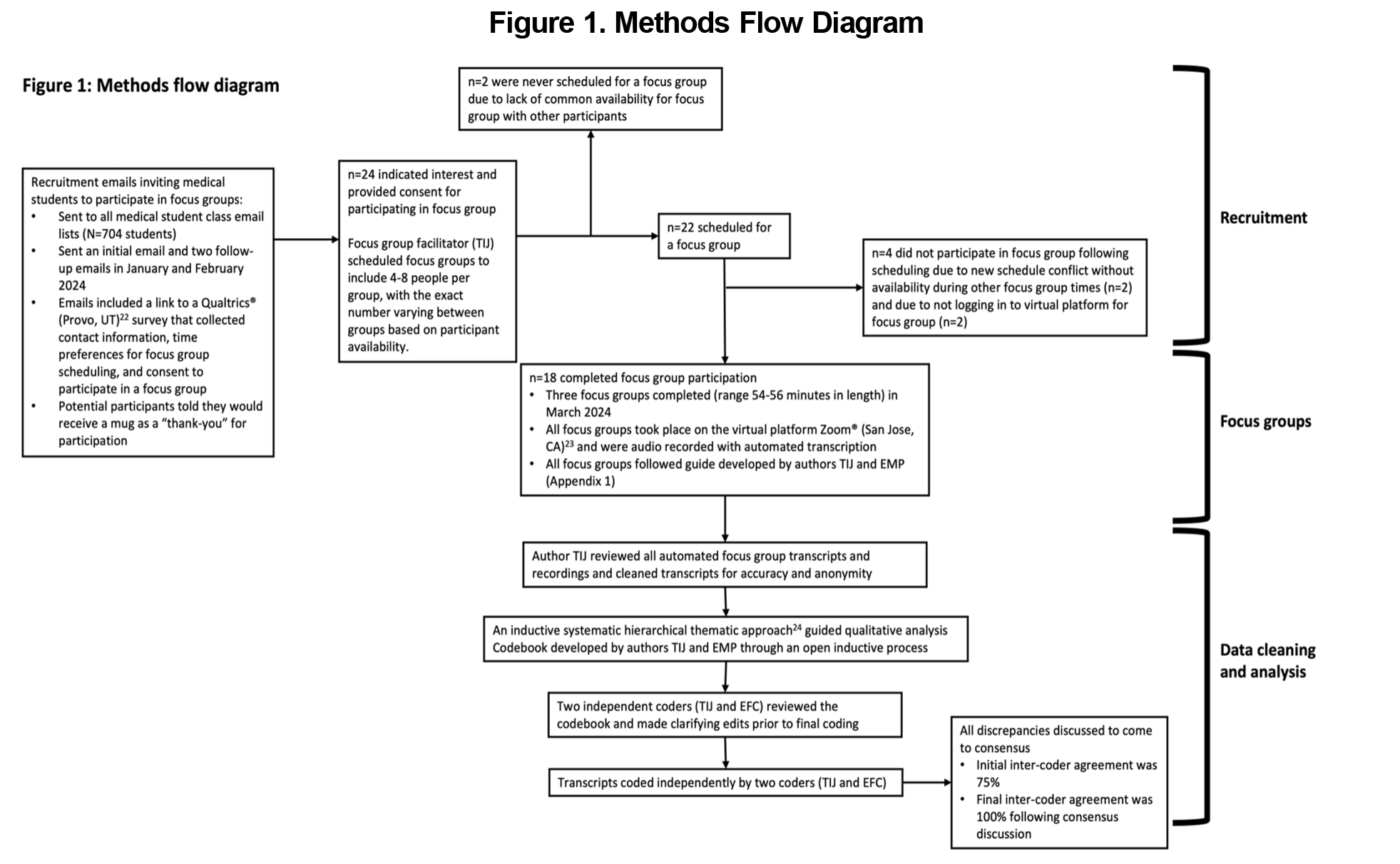

We conducted focus groups of medical students at a single Midwest institution. Figure 1 displays an overview of our methods. The University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board determined this study to be exempt from review.

Data Collection

The facilitator guide included nine questions that were posed to all groups (Appendix 1). The facilitator was a medical student on the research team (T.I.J.). We felt it was necessary to have a facilitator with a comprehensive understanding of the curriculum and used a student facilitator as we anticipated that medical student participants would feel more comfortable expressing their opinions with a peer as opposed to a faculty or staff member. Participants could say as much or little as they wanted and could refrain from responding. To protect anonymity, we did not collect demographics aside from year in school.

Data Analysis

For qualitative thematic analysis we used an inductive systematic hierarchical approach24 (Figure 1).

Demographics

Eighteen medical students participated in three focus groups. This included six first-year medical students, two second-year, four third-year, five fourth-year, and one completing an additional year in a dual degree or research position. Twelve (67%) had participated in clinical rotations.

Inductive Thematic Analysis Findings

The research team identified 13 key themes. These were grouped into three common domains: (1) elements that impacted student learning; (2) aspects participants would change regarding how LGBTQ+ health is taught; and (3) ways the sociopolitical landscape has impacted their education or anticipated career trajectory.

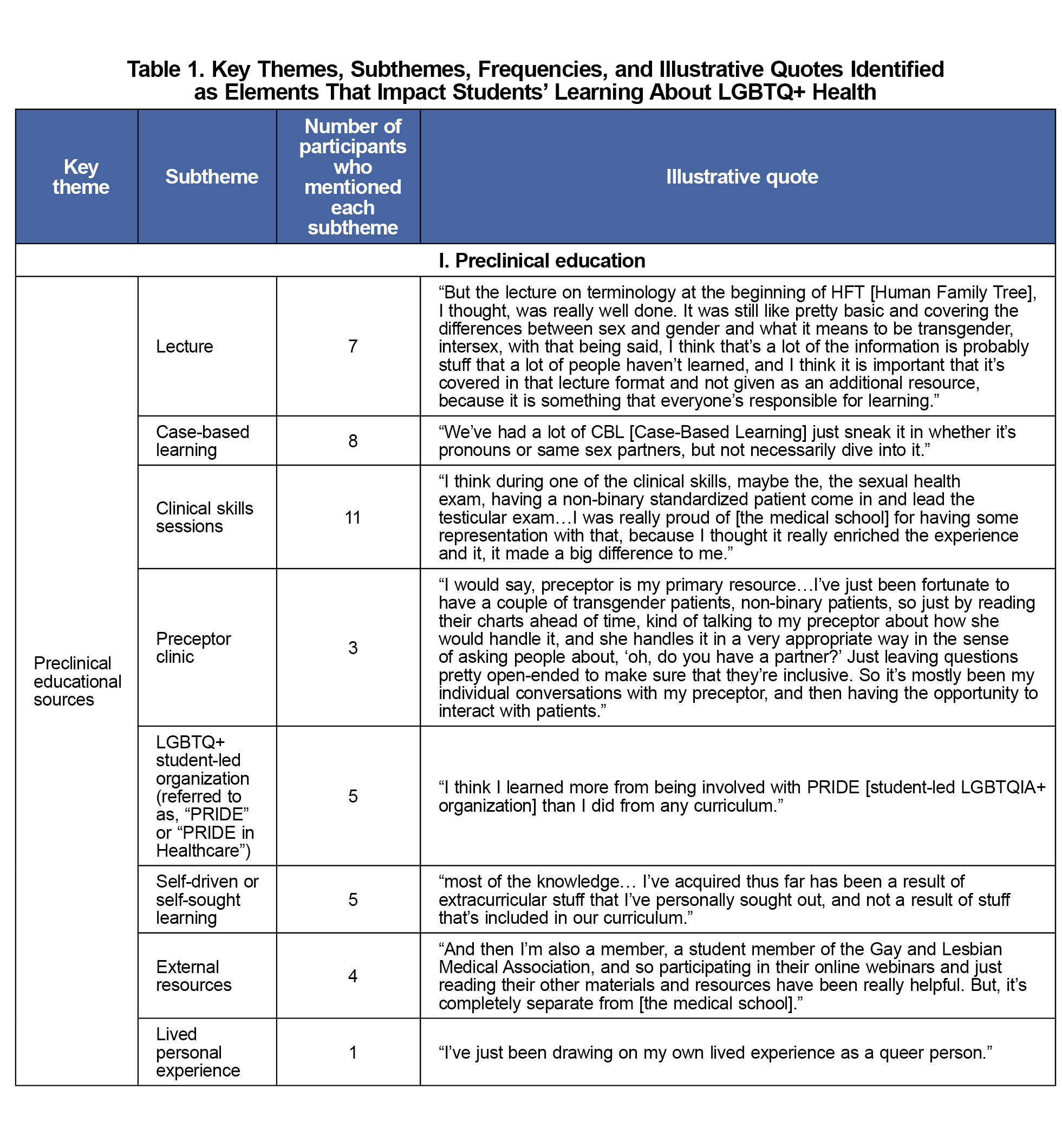

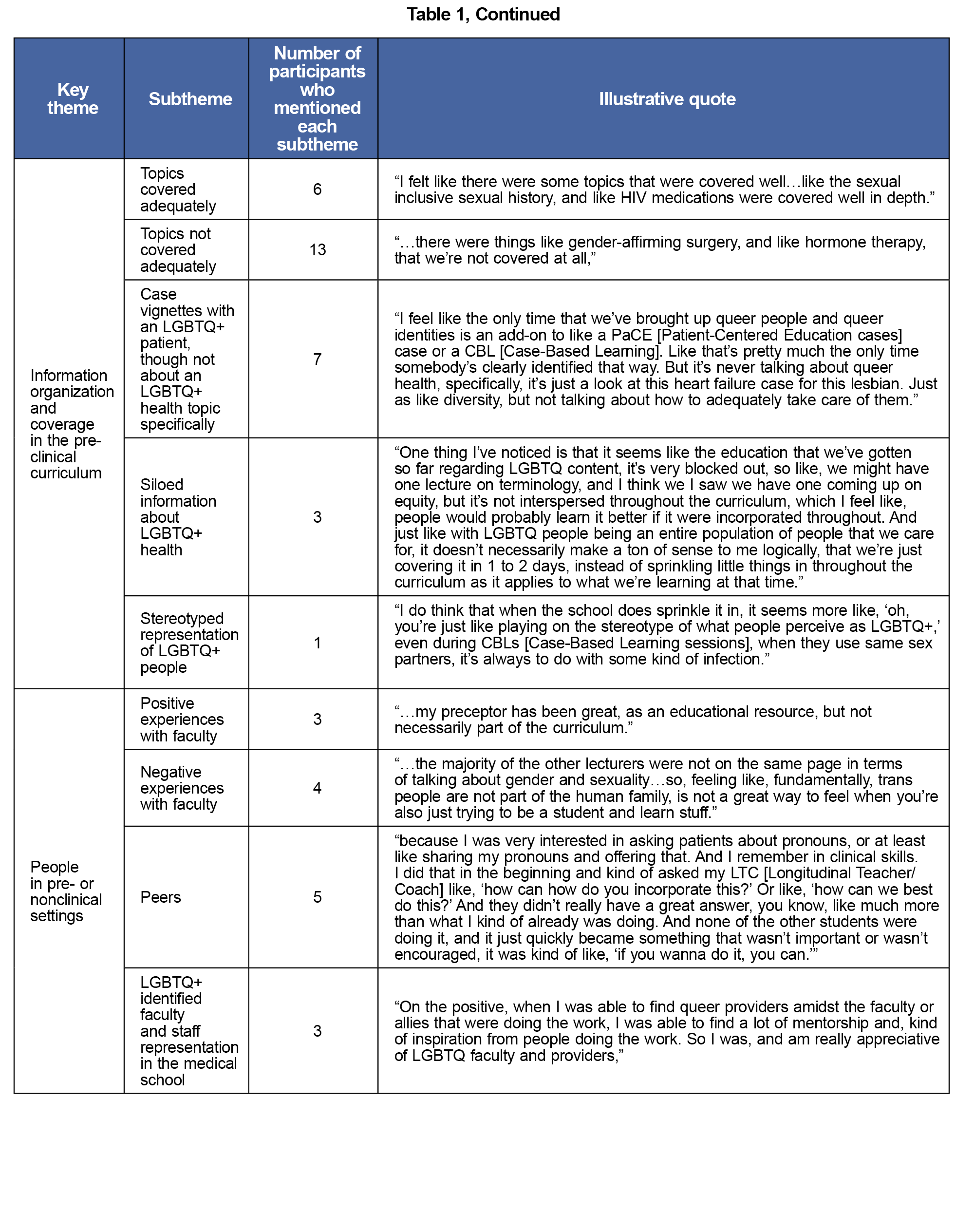

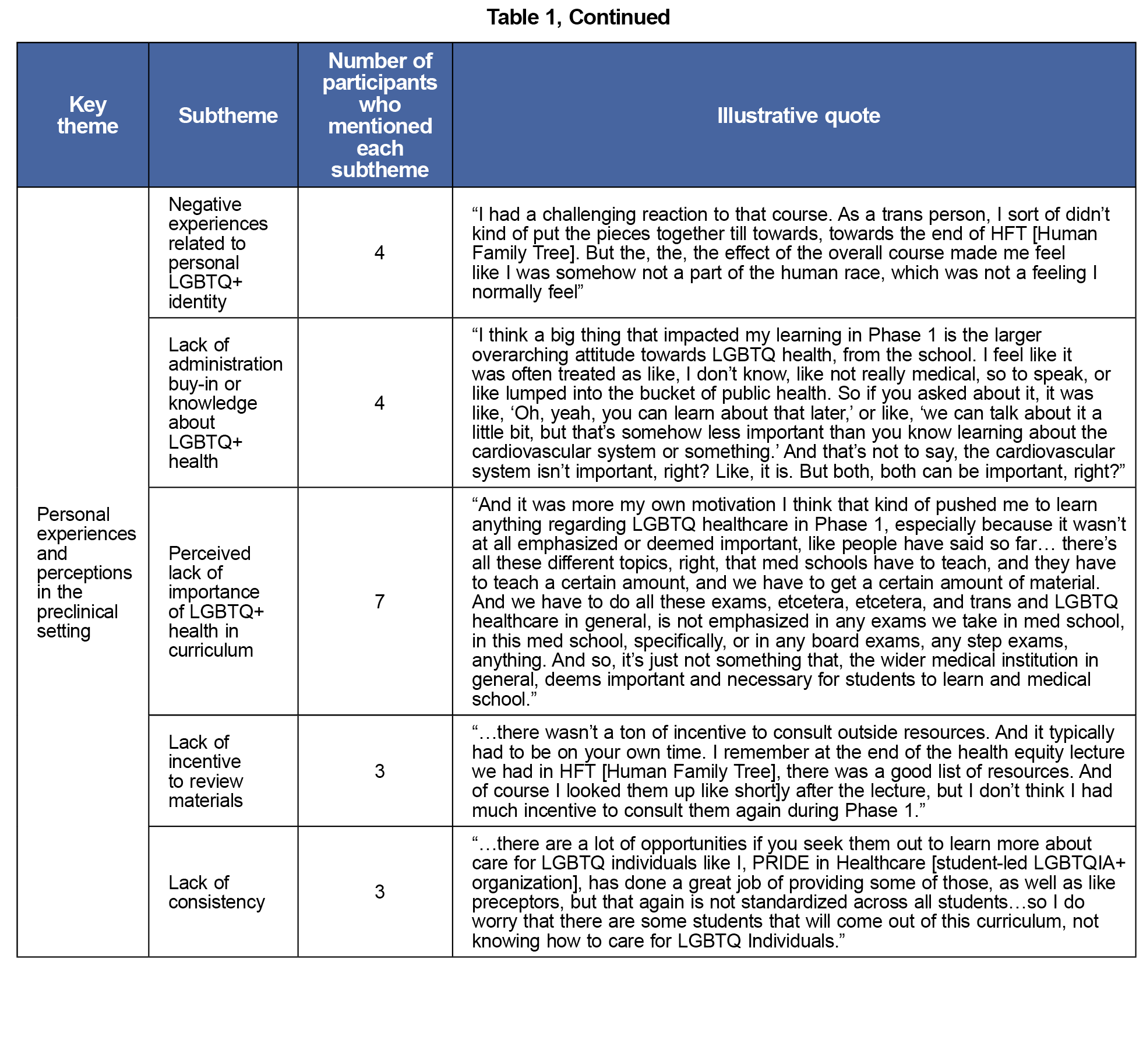

Elements That Impacted Student Learning

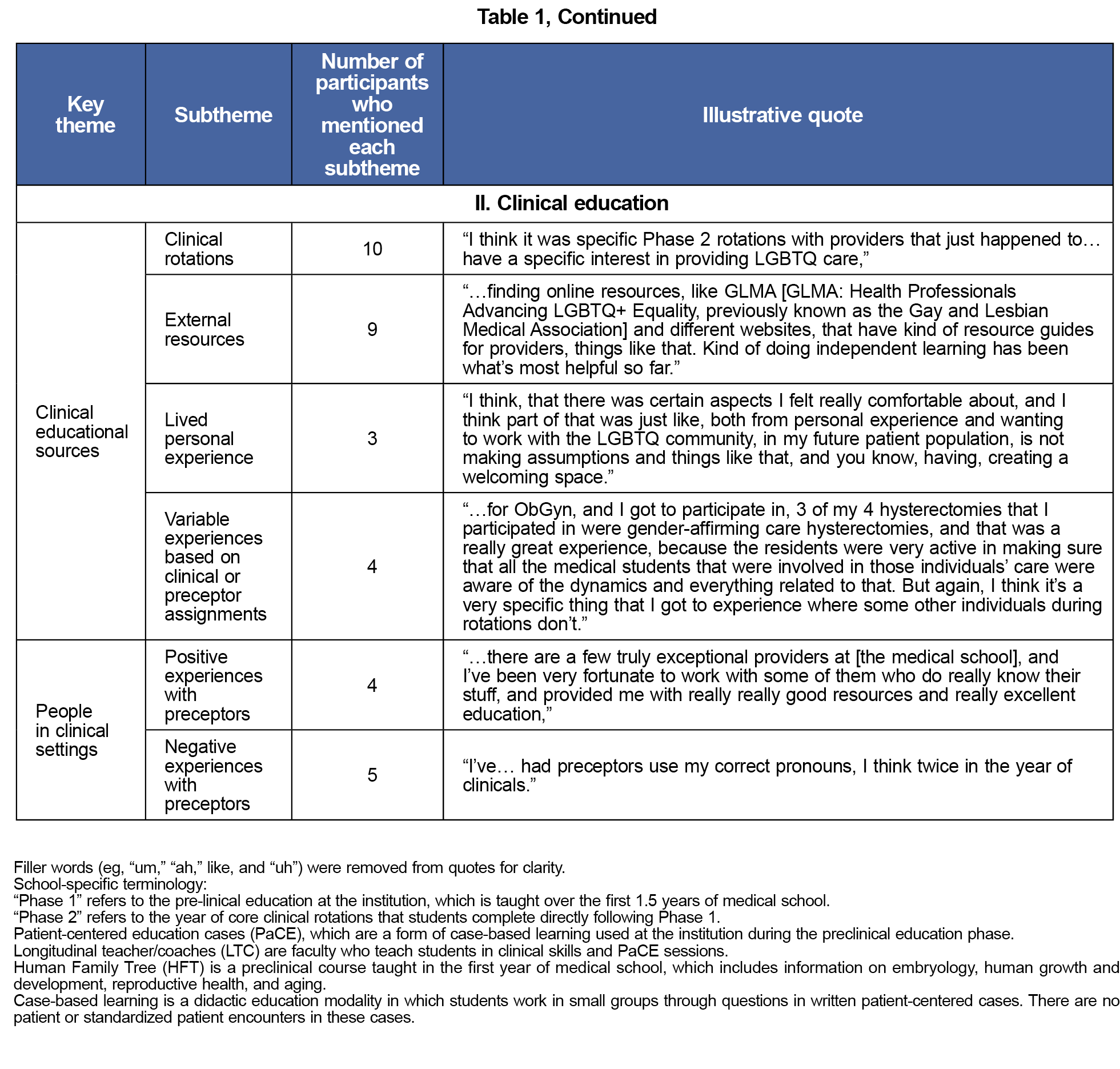

Six key themes represent elements that impacted medical student education on LGBTQ+ health in their preclinical and clinical education (Table 1). These include educational sources (both preclinical and clinical), information organization and coverage, personal experiences, and other people (eg, faculty and peers, in preclinical and clinical settings). The sources were discussed positively, negatively, and neutrally. Lived personal experience was a source of education in the preclinical and clinical settings and also informed negative learning experiences (eg, feeling upset by how their identity was portrayed or excluded). Almost half of the participants who had started clinical rotations reported feeling prepared to engage in aspects of care for LGBTQ+ patients when they began the clinical rotations, most of whom attributed this to their personal lived experience.

Suggestions for Change

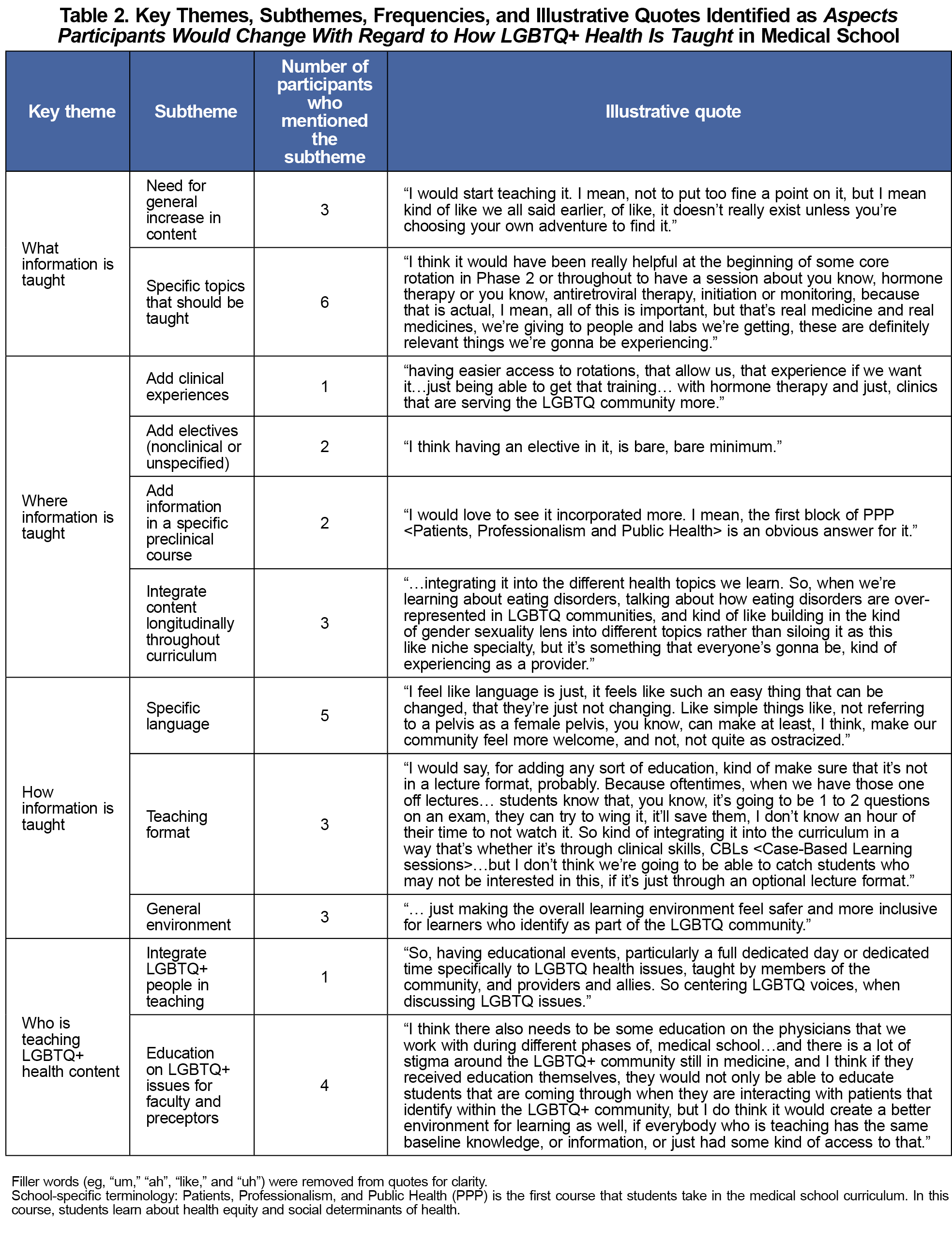

Four key themes were identified related to aspects participants would change with how LGBTQ+ health is taught in this medical school (Table 2). These themes include what, where, how, and by whom LGBTQ+ health information is taught.

Current Sociopolitical Environment

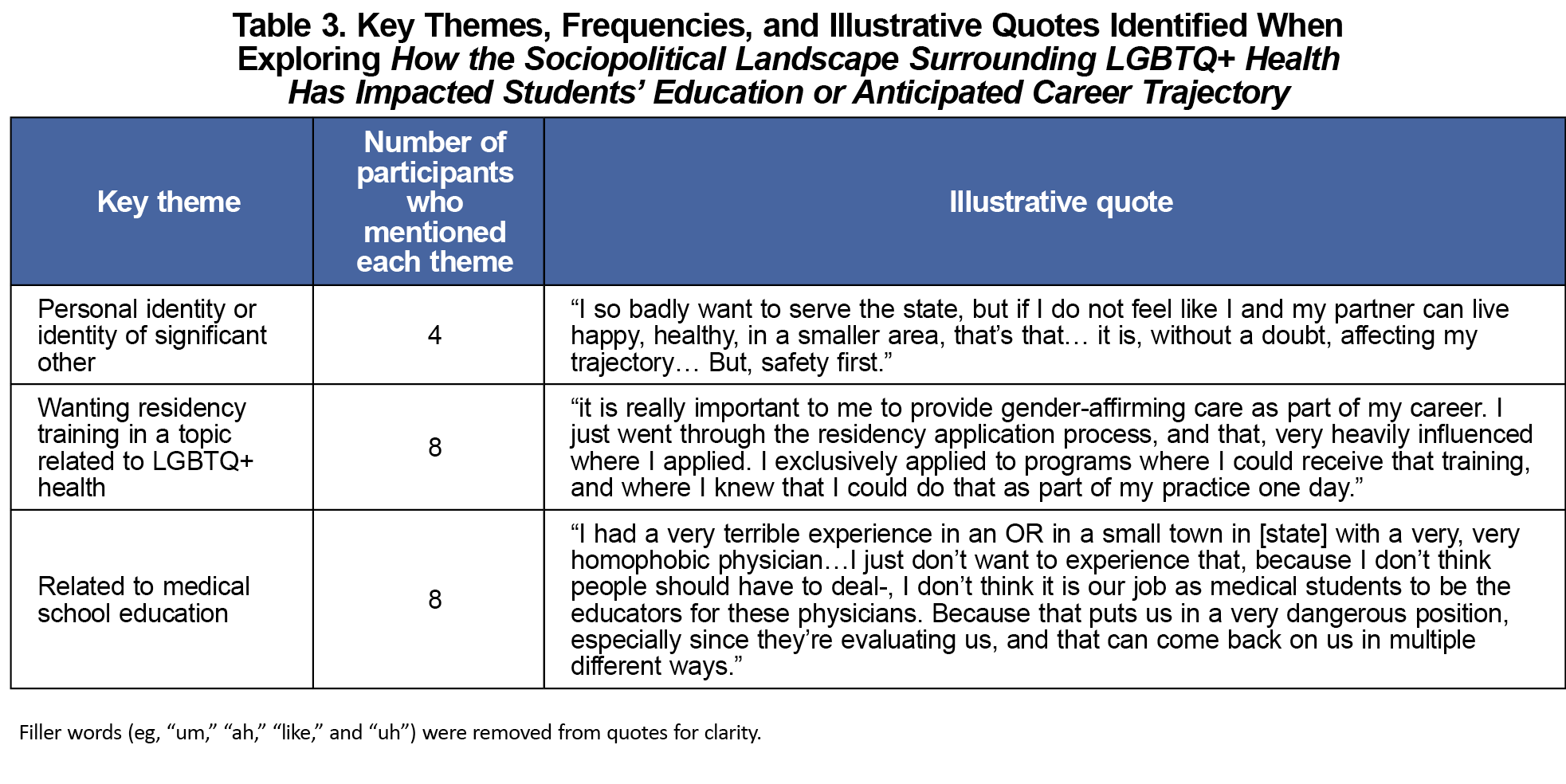

Most participants described at least one way that the current sociopolitical landscape surrounding LGBTQ+ health has impacted their education or anticipated career trajectory. The analysis demonstrated three key themes (Table 3). Specifically, participants described impact due to (1) their personal identity or significant other, (2) desire for residency training in LGBTQ+ health topics, and (3) medical school education.

This study found that medical students describe a range of positive, negative, and neutral experiences learning about LGBTQ+ health. These are informed by various sources in the preclinical and clinical settings, both through intentional programming and the hidden curriculum.25

Similar to findings across medical schools16,17 and reflected in other evaluations at our institution,20,21 focus group participants described the inadequacy of LGBTQ+ health education for medical students. Many evaluations of medical student education on LGBTQ+ health have used surveys,16 and a few studies have used focus groups.26-29 Our study builds upon existing literature by using the depth of focus groups to further explore medical student experiences learning about LGBTQ+ health. This exploration yielded 13 key themes spanning the areas of elements that impacted student education, aspects students would change in this education and ways the sociopolitical environment surrounding LGBTQ+ communities impacts student education or career trajectory.

The themes uncovered in our study found that LGBTQ+ medical students may have negative experiences in both preclinical and clinical learning settings. This aligns with prior studies that found that LGBTQ+ medical students experience discrimination and mistreatment and face a lack of visibility of their identity in medical school curricula.30 Medical schools must understand this multifaceted learning experience, as factors beyond the sheer presence of content may impact medical students’ learning experiences. This likely extends to students’ mental health, as a large study of medical students found that those who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual had eight times greater predicted probability of burnout compared to heterosexual students.31

When beginning clinical rotations, participants who felt prepared to engage in aspects of care for LGBTQ+ individuals often felt so because of their personal lived experiences, not as a result of their preclinical medical education, suggesting that limited positive instances in student education are not sufficient to prepare students to care for LGBTQ+ individuals on clinical rotations. Participants described multiple changes they would make in medical education on LGBTQ+ health, suggesting that in addition to an increase in content, medical schools should increase contact with LGBTQ+ communities and promote cultural competency. Several studies explore LGBTQ+ cultural competency interventions,32 and these may enhance patient interactions and LGBTQ+ medical student experiences as organizational climates become more inclusive.

Most participants described how the sociopolitical landscape surrounding LGBTQ+ health has impacted their education or career, related to personal identity, training goals, and medical education experience. This study contributes to the growing data demonstrating how this may impact the distribution of the physician workforce,14,18,19,33 and suggests that medical schools and residency programs should ensure they offer learning opportunities on LGBTQ+ health and that they provide an inclusive space for LGBTQ+ trainees.

Limitations

This study was likely influenced by selection bias, as only 18 medical students among the total 704 across all classes elected to participate in focus groups. While some participants chose to disclose their own LGBTQ+ identity, we did not explicitly collect this demographic data from each participant, and LGBTQ+ identity, among other demographics, may impact the educational experiences evaluated in this study.

Despite the need for medical education on LGBTQ+ health, gaps persist throughout the preclinical and clinical curricula, including at our study institution. Preclinical medical education may not adequately prepare medical students to participate in aspects of care for LGBTQ+ patients, and learning is influenced by multiple factors outside of the required curriculum content. The current sociopolitical landscape surrounding LGBTQ+ communities may influence where medical students pursue future training and careers due to learning goals, their identity or their significant other. Future studies should explore interventions to improve medical education on LGBTQ+ health by integrating it longitudinally throughout the curriculum, education for teaching faculty on inclusive language, and the impact of the sociopolitical landscape on medical education and the physician workforce.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Author E.M.P. received partial salary support from the Kern National Network funded by the Kern Family Foundation as well as the American Medical Association (AMA) Foundation for her role as LGBTQ+ Health Fellowship Director during the time of this study.

Conflict disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Jones J. LGBTQ+ Identification in U.S. now at 7.6%. Gallup. March 13, 2024. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://news.gallup.com/poll/611864/lgbtq-identification.aspx

- Hughto JMW, Varma H, Babbs G, et al. Disparities in health condition diagnoses among aging transgender and cisgender medicare beneficiaries, 2008-2017. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1102348. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1102348

- Caceres BA, Streed CG Jr, Corliss HL, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Hypertension; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; and Stroke Council. Assessing and addressing cardiovascular health in LGBTQ Adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(19):e321-e332. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000914

- Medina-Martínez J, Saus-Ortega C, Sánchez-Lorente MM, Sosa-Palanca EM, García-Martínez P, Mármol-López MI. Health inequities in LGBT people and nursing interventions to reduce them: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):11801. doi:10.3390/ijerph182211801

- Leone AG, Trapani D, Schabath MB, et al. Cancer in transgender and gender-diverse persons: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(4):556-563. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7173

- Inman EM, Obedin-Maliver J, Ragosta S, et al. Reports of negative interactions with healthcare providers among transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female at birth in the United States: results from an online, cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(11):6007. doi:10.3390/ijerph20116007

- Casey LS, Reisner SL, Findling MG, et al. Discrimination in the United States: experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(Suppl 2)(suppl 2):1454-1466. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13229

- Montero A, Hamel L, Artiga S, Dawson L. LGBT adults’ experiences with discrimination and health care disparities: findings from the KFF Survey of Racism, Discrimination, and Health. KFF. April 2, 2024. Accessed November 17, 2024. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/poll-finding/lgbt-adults-experiences-with-discrimination-and-health-care-disparities-findings-from-the-kff-survey-of-racism-discrimination-and-health/.

- Jaffee KD, Shires DA, Stroumsa D. Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men: implications for improving medical education and health care delivery. Med Care. 2016;54(11):1010-1016. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000583

- Wang T, Geffen S, Cahill S. The current wave of anti-LGBT legislation. The Fenway Institute; 2016. https://fenwayhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Current-Wave-of-Anti-LGBT-Legislation.pdf.

- Peele C. Roundup of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation advancing in states across the country. Human Rights Campaign. May 23, 2023. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://www.hrc.org/press-releases/roundup-of-anti-lgbtq-legislation-advancing-in-states-across-the-country.

- Movement Advancement Project. Bans on best practice medical care for transgender youth. Last updated June 27, 2024. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/healthcare_youth_medical_care_bans.

- Sears B, Castleberry NM, Lin A, Mallory C. LGBTQ People’s Experiences of Workplace Discrimination and Harassment.UCLA School of Law William’s Institute; August 2024. Accessed November 17, 2024. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Workplace-Discrimination-Aug-2024.pdf.

- Ramos N, Jones SA, Bitterman M, Janssen A. Recruitment, retention, and wellbeing of LGBTQ-serving child psychiatrists and mental health providers. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2024;33(1S):e17-e28. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2023.11.002

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: the influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(7):1001-1014. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9

- Jewell TI, Petty EM. LGBTQ+ health education for medical students in the United States: a narrative literature review. Med Educ Online. 2024;29(1):2312716. doi:10.1080/10872981.2024.2312716

- Streed CG Jr, Michals A, Quinn E, et al. Sexual and gender minority content in undergraduate medical education in the United States and Canada: current state and changes since 2011. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):482. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05469-0

- Kurman TM, Ake SN, Hille JJ. Medical Students’ Perspectives on transgender care legislation and its impact on medical residency applications. Sex Gend Policy. 2024;7(2):107-121. doi:10.1002/sgp2.12088

- Jewell TI, Wolfe AM, Petty EM. Impact of gender-affirming care legislation on medical student plans for residency, Transgender Health. 2025. doi:10.1089/trgh.2024.0180

- Jewell TI, Petty EM. Evaluation of LGBTQ+ health education in the pre-clinical curriculum at a public midwest medical school. WMJ. 2025;124(1):35-41.

- Jewell TI, Petty EM. How can pre-clinical preparation to care for LGBTQ+ patients be enhanced? Student insight at a midwest medical school. Poster presentation: GLMA’s Annual Conference on LGBTQ+ Health; September 30 – October 2, 2024. Charlotte, NC.

- Qualtrics. January 2024 ed. Provo, Utah, USA.

- Zoom. Version 5.17.11. San Jose, CA.

- Naeem M, Ozuem W, Howell K, Ranfagni S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2023;22:16094069231205789. doi:10.1177/16094069231205789

- Margolis E, Soldatenko M, Acker S, Gair M. Peekaboo. In: E M, ed. The Hidden Curriculum in Higher Education. Routledge; 2001.

- Ojo A, Singer MR, Morales B, et al. Reproductive justice: a case-based, interactive curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11275. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11275

- White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(3):254-263. doi:10.1080/10401334.2015.1044656

- Toman L. Navigating medical culture and LGBTQ identity. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):335-338. doi:10.1111/tct.13078

- Verbree A-R, Isik U, Janssen J, Dilaver G. Inclusion and diversity within medical education: a focus group study of students’ experiences. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):61. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04036-3

- Danckers M, Nusynowitz J, Jamneshan L, Shalmiyev R, Diaz R, Radix AE. The sexual and gender minority (LGBTQ+) medical trainee: the journey through medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):67. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05047-4

- Samuels EA, Boatright DH, Wong AH, et al. Association between sexual orientation, mistreatment, and burnout among US medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036136. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36136

- Yu H, Flores DD, Bonett S, Bauermeister JA. LGBTQ + cultural competency training for health professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):558. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04373-3

- Das RK, Terhune K, Drolet BC. The influence of anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation on graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(3):287-290. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-23-00276.1

There are no comments for this article.