Clinical rotations are critical for medical education.1,2 It is essential to have physician teachers (preceptors).2 US medical schools are experiencing increasing difficulty recruiting4 and retaining preceptors.4 Family medicine is an important component of most institutions’ clinical rotations.5,6 The University of Colorado School of Medicine (CUSOM) switched to a longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC) with the class of 2025. Students have a half day of family medicine clinic weekly during their clinical year.17 We sought to understand motivations of current, past, and potential family medicine preceptors to ensure we maintain necessary clinical sites. We planned to use this data to guide discussions surrounding recruitment and retention of preceptors.

RESEARCH BRIEF

To Teach or Not to Teach? Incentives and Barriers Impacting Clinical Preceptorship in Family Medicine

Dylan Mechling, MD | Heather Brougham, DO | Carlos Rodriguez, PhD | Julia Kendrick, MA | Melissa Johnson, MD

PRiMER. 2025;9:67.

Published: 12/23/2025 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2025.863726

Background and Objectives: Clinical preceptors serve a vital role in medical education. Recruiting and retaining clinical preceptors, especially in family medicine, is a growing challenge for US medical schools. This study aimed to investigate the incentives and barriers family physicians at the University of Colorado School of Medicine (CUSOM) face when deciding to serve as clinical preceptors, and to explain why these physicians become, remain, and/or stop serving as preceptors.

Method: A cross-sectional survey was distributed to 376 family physicians associated with CUSOM who were active clinical teachers, had been clinical teachers in the past, or were associated with practices that historically had taken medical student learners, with a 60.6% response rate. We calculated descriptive statistics for single-choice, closed-ended survey questions. For the open-ended questions, we adopted a thematic analysis.

Results: The results revealed that intrinsic motivators, such as a love for teaching (76.6%), a sense of duty to the profession (67.8%), and relationships with students (58.5%) were the primary reasons that preceptors chose to teach clinically. Conversely, time (an extrinsic factor), was the largest barrier to teaching that current (80.0%) and potential (51.3%) preceptors faced.

Conclusions: Our results indicate that family physicians largely balance intrinsic motivators against extrinsic barriers when deciding whether to clinically precept medical students. While a longitudinal integrated clerkship model can amplify the impact of these intrinsic motivators, addressing the preceptor shortage may require focus on the motivators that preceptors report as most meaningful and minimizing the impact of the time burden of teaching.

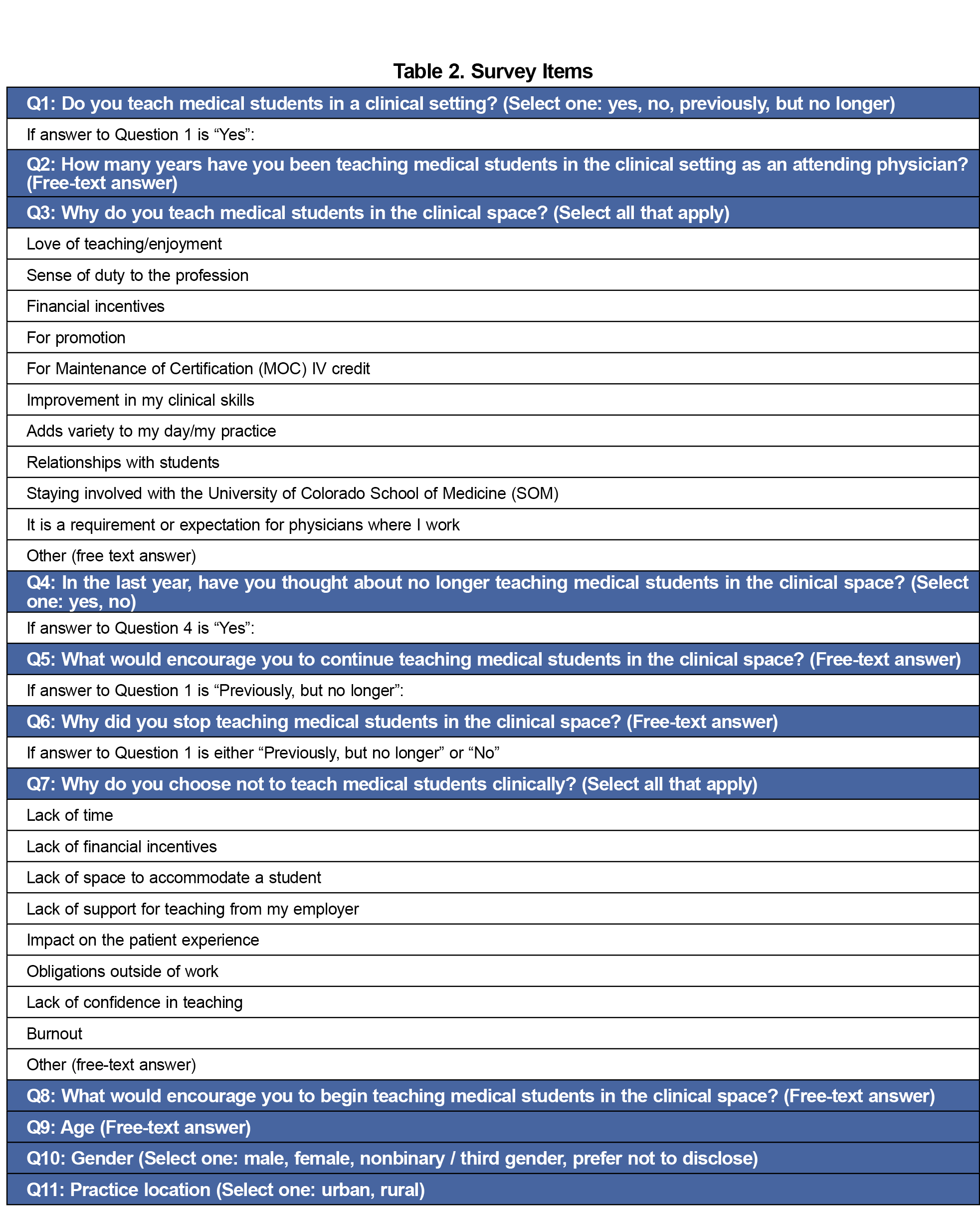

A cross-sectional survey on teaching perspectives was distributed to 376 family medicine physicians associated with CUSOM who were active or past preceptors, or were associated with practices that historically had taken students. There were no parameters set on how long ago a site or provider may have taken learners to be included. The survey was distributed by the Dean of Education via email in May 2024 and closed in July 2024. After receiving institutional review board exemption (#23-1127), we administered this survey (Table 2) in Qualtrics using skip logic to tailor questions to teaching status. Response scales included check-one response, check-all-that-apply, and open-ended comments. The survey was reviewed by family physicians and two expert reviewers.

For single-choice, closed-ended survey questions, we calculated descriptive statistics. For the open-ended questions, we adopted a thematic analysis approach. Two study leads created themes matching responses. They compared theme definitions and appropriateness for the first 10 free-response questions to ensure standardization. Three leads then matched each free-text response to appropriate themes, and we then analyzed the data for the thematic frequency.

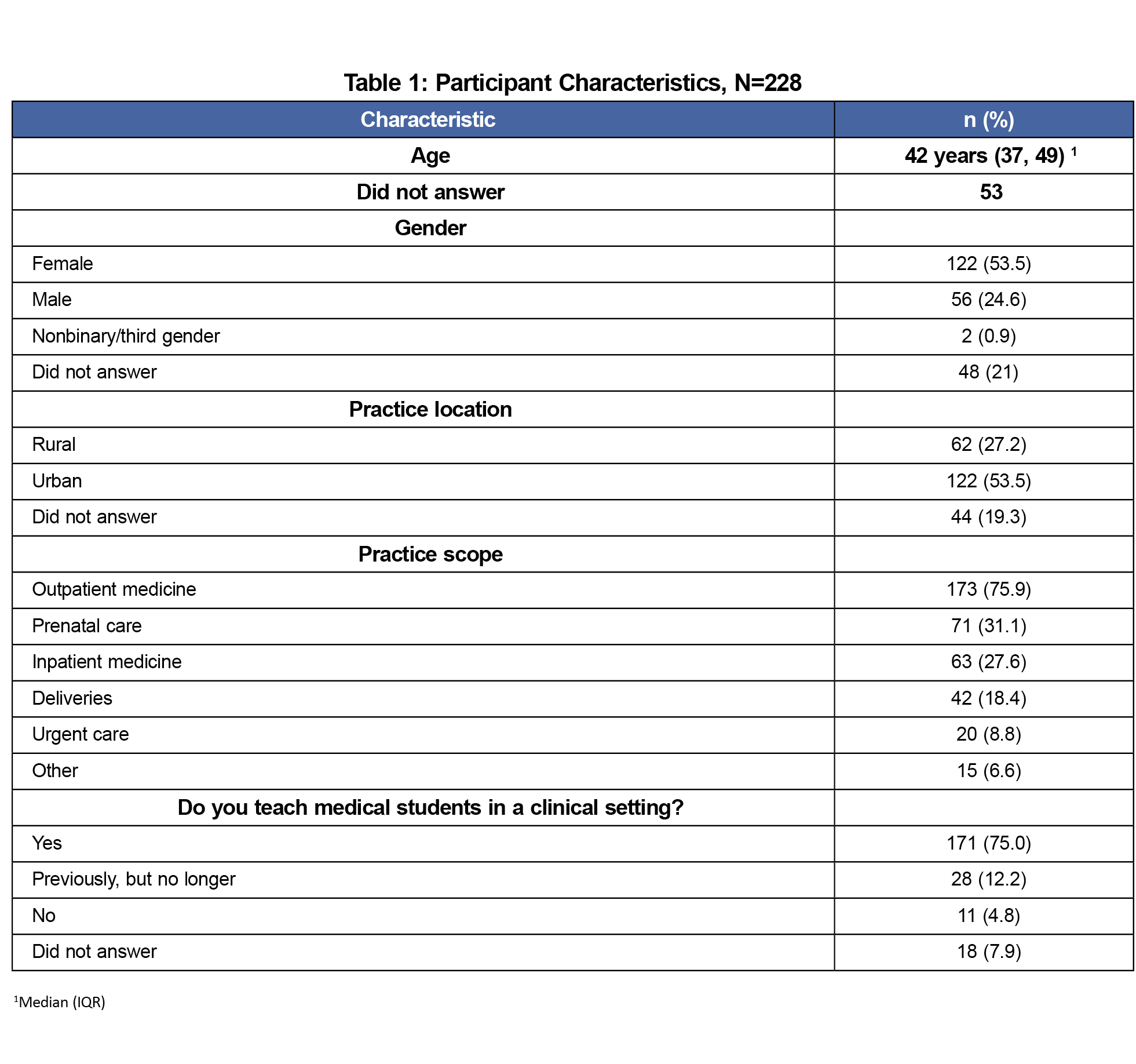

A total of 228/376 (60.7%) family physicians completed the survey (Table 1). Practice scope and practice affiliation of the survey participants varied as is reported in Table 1. The majority (75.0%) of survey participants were current preceptors. Twenty-eight participants (12.2%) were former preceptors and eleven (4.8%) had not been preceptors.

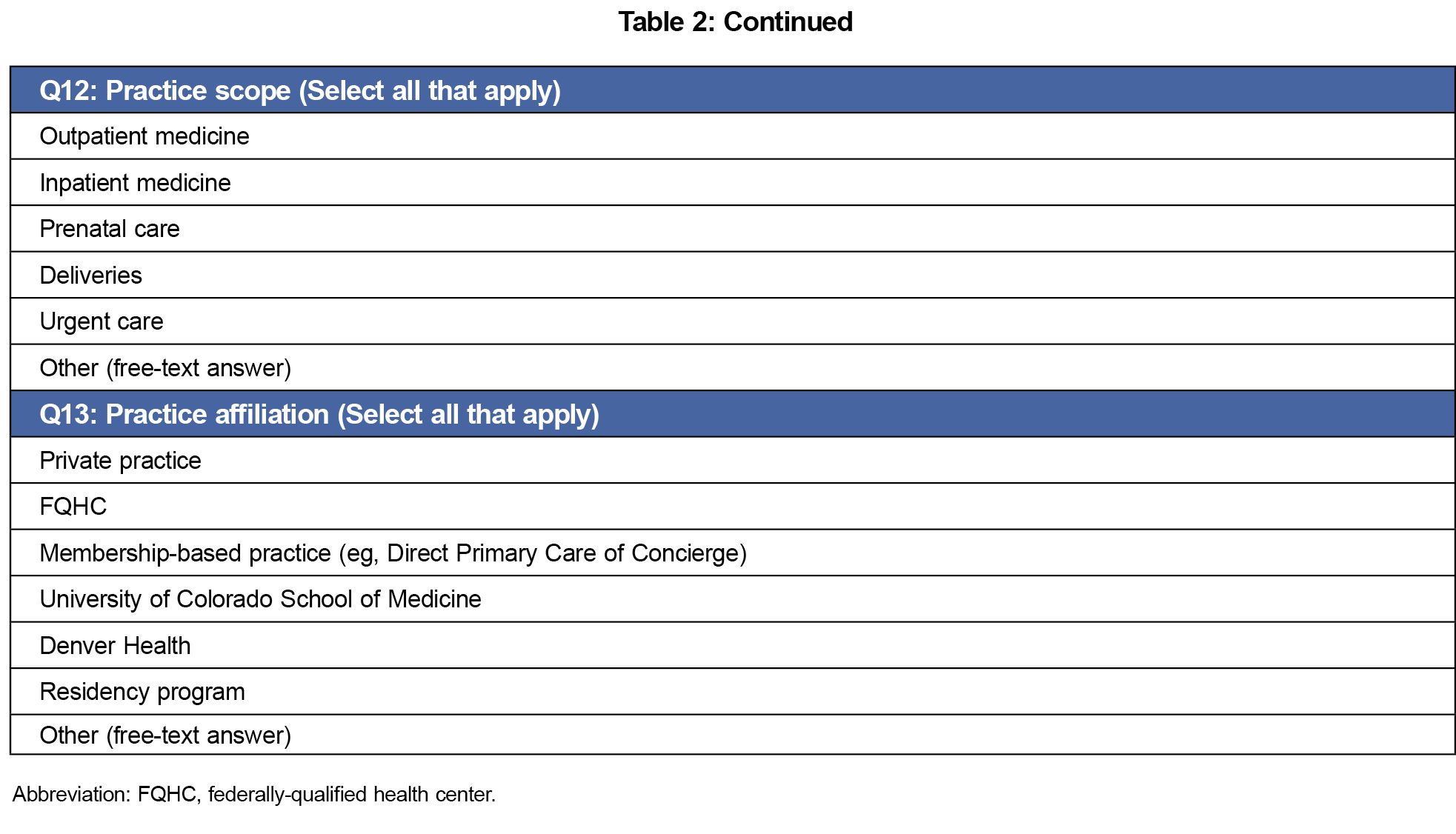

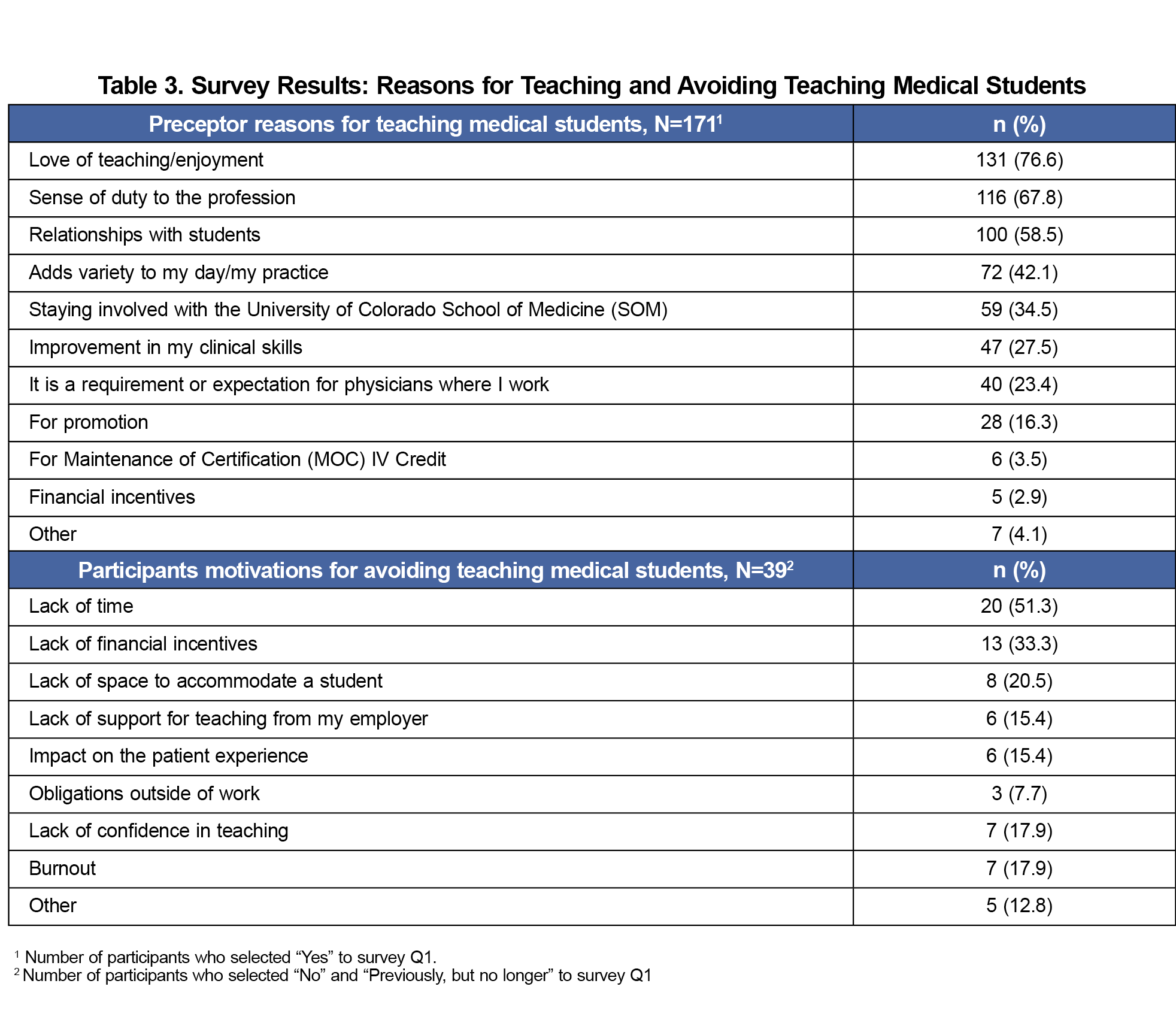

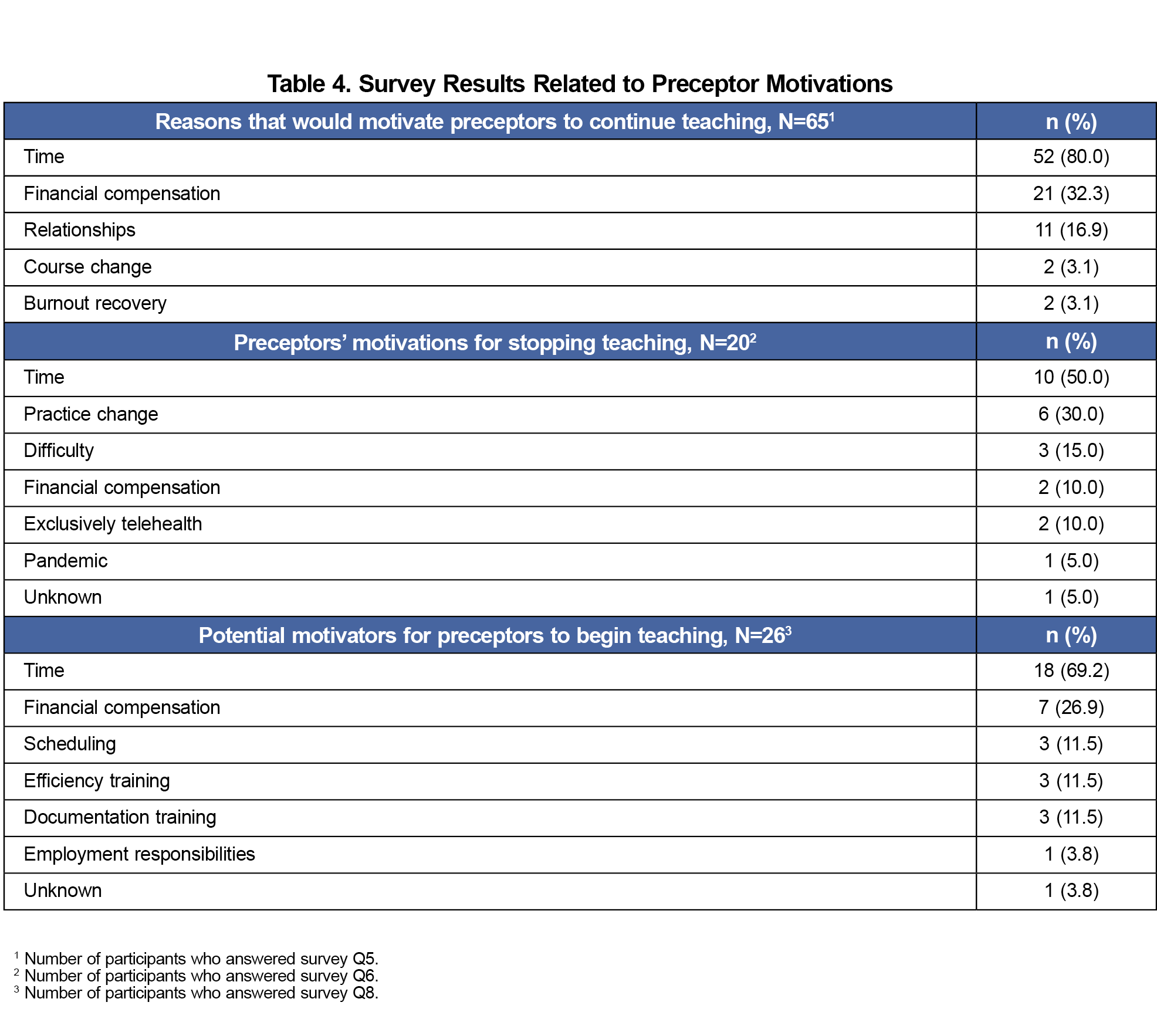

Intrinsic factors were the most common motivators for preceptors (Table 3). Of those currently teaching, the most common motivations include “love for teaching/enjoyment” (76.6%), “sense of duty to the profession” (67.8%), and “relationships with students” (58.5%). A significant percentage (41.5%) of current preceptors had considered no longer clinically teaching. A free-response question explored what could motivate preceptors to continue teaching. A summary of the response themes is shown in Table 4. Dedicated time for teaching without impacting productivity was the most common theme (80.0%). One participant stated:

“Carved out time. A full, busy clinic day is too difficult to manage while also taking good, necessary time to teach and guide a student.”

Eleven of the 39 participants who are not currently teaching have never taught. Their reasons for not teaching included extrinsic barriers (Table 3). The most common was lack of time (51.3%).

Participants who stated that they had stopped teaching clinically were queried regarding their reasoning. A thematic summary of the responses is shown in Table 4. The time demands of teaching was the most cited reason (50.0%). One participant explained:

“Having medical students takes significant time. On days that I had a student, I found myself either being behind, not finishing notes, not doing inbasket, or doing a very poor job teaching ...”

Participants who had never taught were asked what could motivate them to teach (Table 4). Time dedicated to teaching without impacting productivity was the most common theme (69.2%). The other common themes were direct financial compensation (26.9%), changes in the way students or preceptors are scheduled (11.5%), faculty development on efficiency (11.5%), and job logistics (11.5%).

Our study evaluated the motivations of family physicians when deciding whether to serve as preceptors. The love of teaching was the most frequently-cited reason for teaching followed by duty to the profession, and relationships. These motivators may also be influenced by the pool of physicians being those who were or had been affiliated with teaching. Financial incentives ranked last as a motivating factor (2.9%), differing from current literature.7,12,20 However, 32.3% of current preceptors said that financial compensation would motivate them to continue teaching, 33.3% of nonpreceptors noted the lack of financial compensation as a factor in their decision not to teach, and 26.9% listed it as a potential motivating factor to begin teaching.

Our finding that time is the greatest barrier to preceptor recruitment and retention aligns with current research.4,7,13 Dedicated time for teaching was mentioned by 80% as a motivating factor to continue teaching, 50% as a reason they stopped teaching, and 69% as a potential motivating factor to begin teaching.

While 60.6% of survey recipients completed the survey, there is the potential for nonparticipation bias. We have considered that those who did not respond may be those most constrained by time or possibly less invested in the mission of the school. The number of respondents that selected specific themes limits our ability to assess differences based on demographic variables such as gender and age or practice settings with statistical significance. While we anticipate that the LIC model reduces time burden on preceptors who previously had students daily, this survey was completed just after a curriculum transition which makes positive and/or negative impact difficult to assess and limits our study’s generalizability to other medical schools. Given the broad scope of family medicine, there may be limited generalizability to other specialties.

Recruiting and retaining family medicine preceptors is a challenge for medical schools across the country. Our findings align with existing research that physicians largely balance intrinsic motivators with extrinsic barriers, however our study showed less emphasis on financial incentives. The largest motivator is the love of teaching, and the largest barrier is lack of time. Literature on efficient precepting is growing from bedside teaching and broadening student responsibilities to creative patient scheduling.19 We plan to work closely with department leadership to discuss opportunities to reduce the time barrier placed on family medicine preceptors.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: This project has received funding through the University of Colorado School of Medicine Department of Family Medicine, both through the student research funding program and the Pilot and Exploratory Program.

Presentations: Content from this study was presented at the AMC Education and Innovation Symposium on May 1, 2024, and at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Conference on Medical Student Education on February 1, 2025.

Conflict Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Krehnbrink M, Patel K, Byerley J, et al. Physician preceptor satisfaction and productivity across curricula: A comparison between longitudinal integrated clerkships and traditional block rotations. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(2):176-183. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1687304

- Snow SC, Gong J, Adams JE. Faculty experience and engagement in a longitudinal integrated clerkship. Med Teach. 2017;39(5):527-534. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1297528

- Cox WJ, Desai GJ. The crisis of clinical education for physicians in training. Mo Med. 2019;116(5):389-391.

- Minor S, Huffman M, Lewis PR, Kost A, Prunuske J. Community preceptor perspectives on recruitment and retention: the CoPPRR study. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):389-398. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.937544

- Clerkship requirements by Discipline. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/data/clerkship-requirements-discipline

- The specialty of family medicine. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2020. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www.aafp.org/about/dive-into-family-medicine/family-medicine-speciality.html

- Ryan MS, Vanderbilt AA, Lewis TW, Madden MA. Benefits and barriers among volunteer teaching faculty: comparison between those who precept and those who do not in the core pediatrics clerkship. Med Educ Online. 2013;18(1):1-7. doi:10.3402/meo.v18i0.20733

- Lacroix TB. Meeting the need to train more doctors: the role of community-based preceptors. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;10(10):591-594. doi:10.1093/pch/10.10.591

- Theobald M, Rutter A, Steiner BD. A bonus, not a burden: how medical students can add value to your practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2021;28(5):5A-5C.

- Kumar A, Kallen DJ, Mathew T. Volunteer faculty: what rewards or incentives do they prefer? Teach Learn Med. 2002;14(2):119-123. doi:10.1207/S15328015TLM1402_09

- Rodríguez C, Bélanger E, Nugus P, et al. Community preceptors’ motivations and views about their relationships with medical students during a longitudinal family medicine experience: A qualitative case study. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(2):119-128. doi:10.1080/10401334.2018.1489817

- Peters AS, Schnaidt KN, Zivin K, Rifas-Shiman SL, Katz HP. How important is money as a reward for teaching? Acad Med. 2009;84(1):42-46. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318190109c

- Oliveira Franco RL, Martins Machado JL, Satovschi Grinbaum R, Martiniano Porfírio GJ. Barriers to outpatient education for medical students: a narrative review. Int J Med Educ. 2019;10:180-190. doi:10.5116/ijme.5d76.32c5

- Graziano SC, McKenzie ML, Abbott JF, et al. Barriers and strategies to engaging our community-based preceptors. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(4):444-450. doi:10.1080/10401334.2018.1444994

- Teherani A, O’Brien BC, Masters DE, Poncelet AN, Robertson PA, Hauer KE. Burden, responsibility, and reward: preceptor experiences with the continuity of teaching in a longitudinal integrated clerkship. Acad Med. 2009;84(10)(suppl):S50-S53. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b38b01

- Latessa R, Schmitt A, Beaty N, Buie S, Ray L. Preceptor teaching tips in longitudinal clerkships. Clin Teach. 2016;13(3):213-218. doi:10.1111/tct.12416

- Trek curriculum. University of Colorado Anschutz. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/education/current-students/curriculum/trek-curriculum

- Poncelet A, Bokser S, Calton B, et al. Development of a longitudinal integrated clerkship at an academic medical center. Med Educ Online. 2011;16(1):5939. doi:10.3402/meo.v16i0.5939

- Biagioli FE, Chappelle K. How to be an efficient and effective preceptor. Fam Pract Manag. 2010;17(3):18-21.

- Kumar A, Loomba D, Rahangdale RY, Kallen DJ. Rewards and incentives for nonsalaried clinical faculty who teach medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(6):370-372. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00341.x

Lead Author

Dylan Mechling, MD

Affiliations: University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Co-Authors

Heather Brougham, DO - University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Carlos Rodriguez, PhD - Univesity of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Julia Kendrick, MA - University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Melissa Johnson, MD - University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Corresponding Author

Melissa Johnson, MD

Correspondence: University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.