Background: The University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM) and other medical schools utilize a distributed medical education (DME) model to train medical students in real-world community settings. An inherent challenge in this model is maintaining high-quality teaching across large geographic areas and clinical settings. This study compares student perceptions of rural and nonrural preceptor teaching in the UWSOM-required clerkships.

Methods: Our study analyzed 41,684 medical student evaluations of preceptors from six required clerkships and over 4 clerkship school years. Using the Rural-Urban Commuting Area definitions, we categorized individual evaluations as either “rural” or “nonrural”. We used Welch’s unpaired t tests and descriptive statistics to compare rural and nonrural evaluation results.

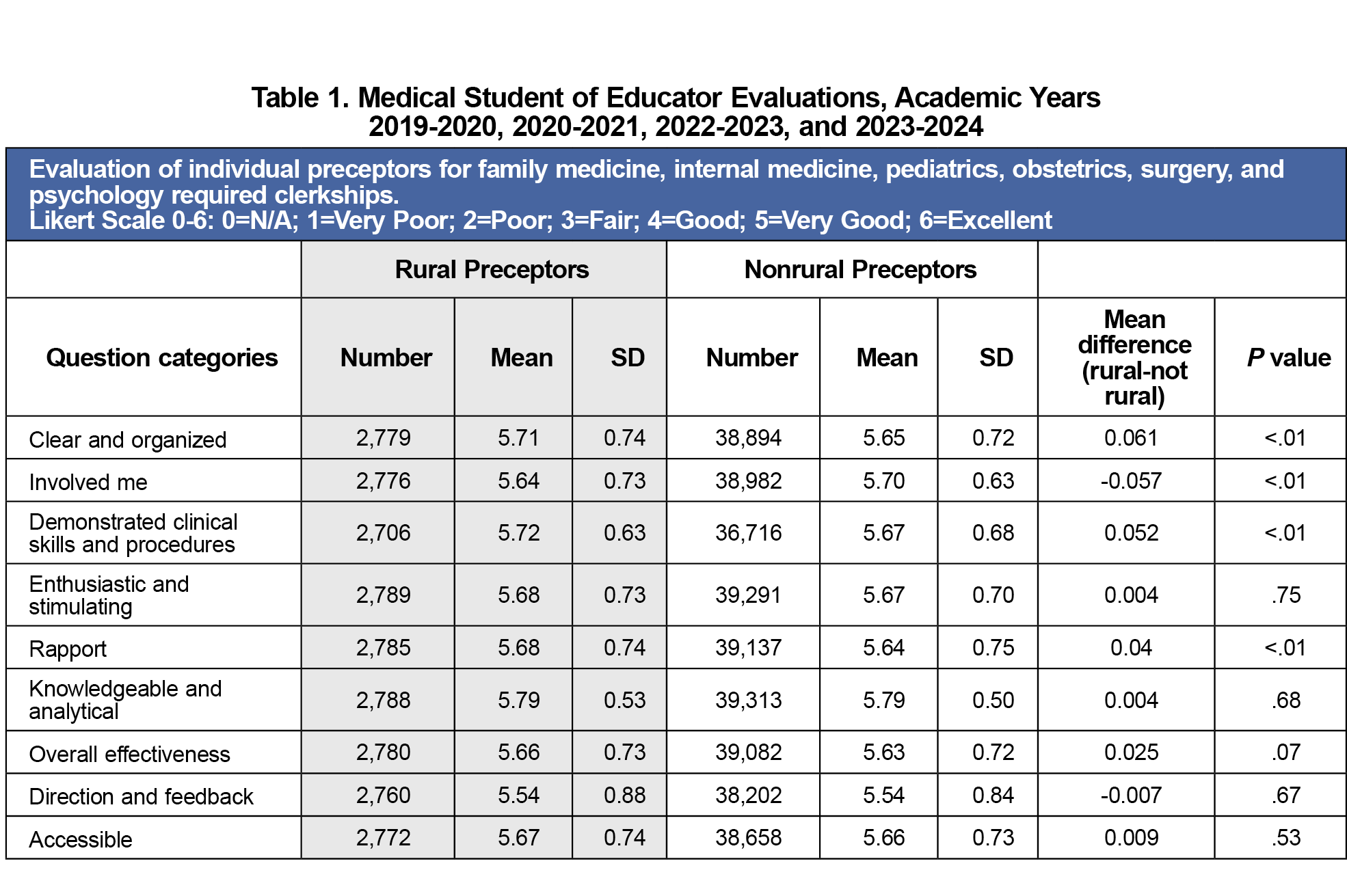

Results: The evaluation data showed high ratings of preceptor teaching across all nine teaching evaluation categories for both rural and nonrural preceptors, with mean scores of 5.5 or higher on a 6-point Likert scale. Rural preceptors slightly outperformed their nonrural counterparts in seven out of nine teaching categories, including three categories reaching statistical significance.

Conclusions: Results suggest that Liaison Committee on Medical Education standards for comparable educational experiences are being met across distributed sites. We recommend a thematic analysis of student evaluation comments to contextualize the findings reported in our study.

The University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM) and other medical schools utilize a distributed medical education (DME) model to train medical students in real-world community settings. Since the early 1970s, UWSOM has delivered DME across a five-state region, pairing students with both rural and urban preceptors.1,2

Although there is broad geographic diversity among the clinical sites in the UWSOM’s DME model, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education(LCME) standards require comparable educational experiences.3 When differences among sites are detected, programs must implement corrective action and track them through continuous quality improvement processes.3 In rural settings, preceptors often face workforce shortages, geographic isolation, and limited faculty-development opportunities that may undermine teaching quality.4,5 These issues may make it difficult for rural teaching sites to maintain parity with their urban counterparts. Only three small, single-specialty studies, each more than a decade old, compared rural and urban teaching quality and found no differences.6-8 Contemporary, multispecialty evidence is lacking in this area.

To fill this gap, we analyzed Medical Student of Educator Evaluation (MSEE) data from six required clerkships (family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, pediatrics, internal medicine, surgery, and psychiatry) at rural versus nonrural sites. One study asked:

- Do students rate preceptor teaching quality differently at rural versus nonrural sites overall?

- Within each clerkship, do rural and nonrural ratings differ?

Understanding whether DME achieves teaching equivalence across settings will inform program design and targeted faculty development.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of Medical Student of Educator Evaluations (MSEEs) submitted by UWSOM medical students after required clerkships in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery, psychiatry, and obstetrics/gynecology during academic years 2019-2020 to 2022-2023. The UW Human Subjects Division determined this study is human subject research but was given exempt status (STUDY00018494). All student identifiers were removed before our analysis.

The sample included 41,684 MSEEs. Each MSEE reflects one student’s rating of a single preceptor. The MSEE has nine Likert-scale items (1 = very poor to 6 = excellent), “N/A” responses were excluded. We also excluded free-text and learning-environment items (Figure 1).

We assigned teaching sites Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes via a database query (January 2024–February 2024). Sites with RUCA ≥ 4 (population ≤ 49,999) were classified as rural; RUCA 1-3 sites were nonrural.9 Clerkship schedules are generated centrally with limited student choice, reducing selection bias. Ten percent of students participate in rural longitudinal integrated clerkships (LICs). LICs have been documented as having higher student satisfaction, which is due in part to the continuity of entrustment between students and preceptors, as well as between students and patients and providers.10,11 Additionally, unlike other students who are assigned rotations, these students apply for and are selected to participate in these rural LICs. For these reasons, we have excluded LIC student scores from this study.

We calculated descriptive statistics for rural versus nonrural groups overall and within each clerkship. We compared group means using Welch’s unpaired t test, which accommodates unequal variances and sample sizes.12

Table 1 presents the MSEE data in aggregate for all six required clerkships, comparing rural and nonrural preceptor teaching. Over this 4-year period, 41,684 student evaluations of preceptors were completed. Rural preceptors made up 2,788 of these evaluations. Across all nine teaching categories, both rural and nonrural mean scores were ≥ 5.23 on a 1–6 scale. Rural preceptors scored marginally higher in seven out of the nine domains.

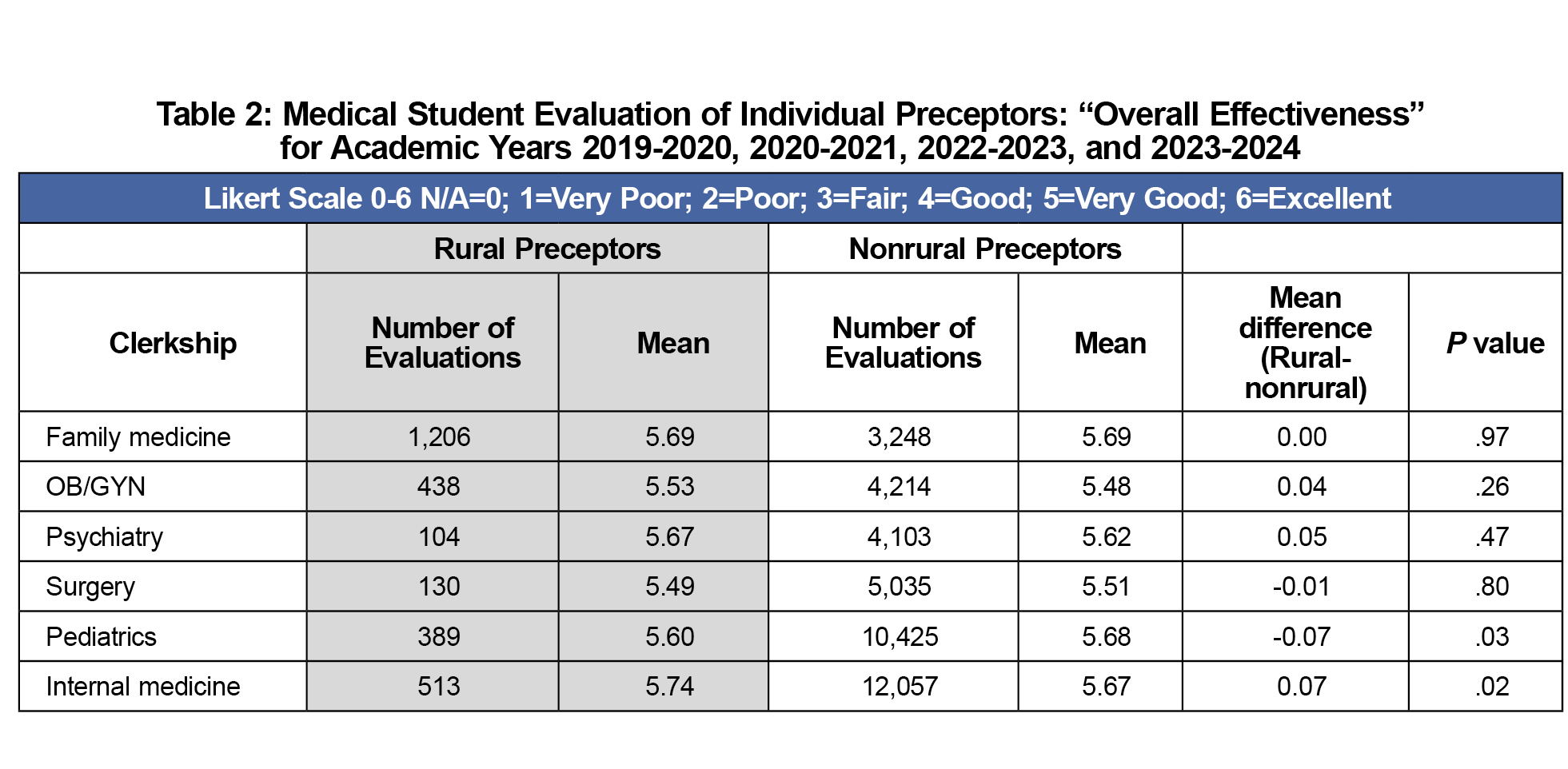

“Overall Effectiveness” scores are shown in Table 2. Rural internal medicine preceptors had the highest scores (5.74). Pediatrics and internal medicine clerkships both showed small but statistically significant rural–urban differences (pediatrics: 5.60 rural vs 5.68 nonrural, P=.03) and (internal medicine 5.74 rural vs 5.67 nonrural, P = .02). No other clerkship differences reached significance.

Analysis of 41,684 student evaluations showed that rural and nonrural preceptors were both highly rated. However, rural preceptors slightly outperformed their nonrural counterparts in seven out of nine teaching categories, including three categories reaching statistical significance. In our analysis of specific required clerkships, again, rural preceptors’ mean scores of “Overall Teaching Effectiveness” were equal to or greater than nonrural mean scores in four out of six clerkships. In sum, rural preceptor teaching not only matches but frequently surpasses their nonrural peers.

The results of this study suggest that LCME standards for comparable educational experiences are being met across distributed sites.3 Although rural preceptors were higher rated in many categories, mean scores of both rural and nonrural preceptors were clustered near the ceiling of the scale. These findings provide assurance to learners, faculty, and accreditors that the geographic diversity of training sites does not compromise educational quality, but instead reflects the strength of the DME model in delivering excellence across various settings.

Medical schools often find it difficult to maintain enough clinical teaching sites, particularly in rural areas. Juggling clinical productivity and teaching creates a significant dilemma for many rural physicians.13,14 To sustain the DME model's effectiveness in rural settings, more needs to be done to support overburdened rural preceptors. This includes innovative faculty development, direct payments and tax incentives, and emphasizing value-added student clinical activities.13-15

Our study's limitations include reliance on student-reported data, which may be inflated by social desirability bias or concerns about anonymity. Further, given the large number of evaluations in this study, reaching a statistical difference may not indicate a meaningful educational difference. Additionally, this study was conducted at a single institution, which limits its generalizability. This study also lacks information on student identity and does not link evaluations to eventual practice locations. Finally, our study did not include the free-text comments by students. We recommend a thematic analysis of student evaluation comments to contextualize the findings reported in this study.

Acknowledgments

Conflict Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Norris TE, Coombs JB, House P, Moore S, Wenrich MD, Ramsey PG. Regional solutions to the physician workforce shortage: the WWAMI experience. Acad Med. 2006;81(10):857-862. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000238105.96684.2f

- Ramsey PG, Coombs JB, Hunt DD, Marshall SG, Wenrich MD. From concept to culture: the WWAMI program at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2001;76(8):765-775. doi:10.1097/00001888-200108000-00006

- Function and Structure of Medical School. Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading ot the MD Degree.Association of American Medical Colleges and American Medical Association; 2025.

- Zhang D, Son H, Shen Y, et al. Assessment of Changes in Rural and Urban Primary Care Workforce in the United States From 2009 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2022914. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22914

- Alexandraki I, Kern A, Beck Dallaghan GL, Baker R, Seegmiller J. Motivators and barriers for rural community preceptors in teaching: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2024;58(6):737-749. doi:10.1111/medu.15286

- Irigoyen MM, Kurth RJ, Schmidt HJ. Learning primary care in medical school: does specialty or geographic location of the teaching site make a difference? Am J Med. 1999;106(5):561-564. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00072-8

- Kamien M. A comparison of medical student experiences in rural specialty and metropolitan teaching hospital practice. Aust J Rural Health. 1996;4(3):151-158. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.1996.tb00203.x

- Carmody DF, Jacques A, Denz-Penhey H, Puddey I, Newnham JP. Perceptions by medical students of their educational environment for obstetrics and gynaecology in metropolitan and rural teaching sites. Med Teach. 2009;31(12):e596-e602. doi:10.3109/01421590903193596

- Rural-urban commuting area codes. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed May 2, 2022, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes

- Eshel R, Hershkovitz R, Katz A, Orkin J, Amar S. Educational outcomes of the first longitudinal integrated clerkship program in Israel. Int J Med Educ. 2021;12:152-153. doi:10.5116/ijme.60f5.ef72

- Paulus R, Byler D, Casapulla S. Student and Preceptor Experiences in a Mini Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship: A Participatory Self-Study. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2020;4:24. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2020.439679

- Ruxton GD. The unequal variance t-test is an underused alternative to Student’s t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test. Behav Ecol. 2006;17(4):688-690. doi:10.1093/beheco/ark016

- Minor S, Huffman M, Lewis PR, Kost A, Prunuske J. Community Preceptor Perspectives on Recruitment and Retention: The CoPPRR Study. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):389-398. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.937544

- Irby DM. Where have all the preceptors gone? Erosion of the volunteer clinical faculty. West J Med. 2001;174(4):246. doi:10.1136/ewjm.174.4.246

- Graziano SC, McKenzie ML, Abbott JF, et al. Barriers and Strategies to Engaging Our Community-Based Preceptors. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(4):444-450. doi:10.1080/10401334.2018.1444994

There are no comments for this article.