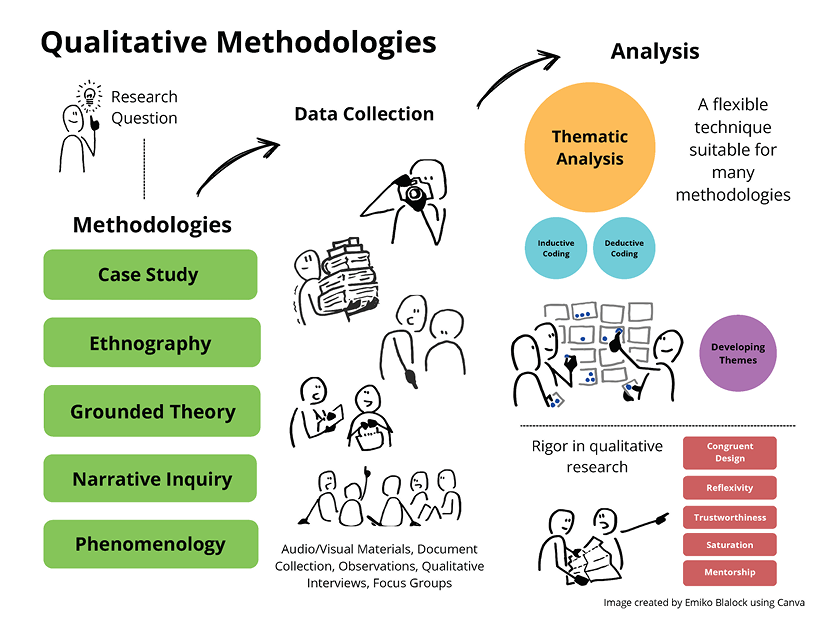

This methodological brief gives an overview of qualitative research methods used in medical education and offers resources to help researchers explore qualitative methods more deeply. We discuss five common qualitative approaches used in medical education research, including case study, ethnography, grounded theory, narrative inquiry, and phenomenology. We review specific qualitative methods and data collection techniques, considering the potential advantages, challenges and biases of each technique. We address the importance of rigor in qualitative research, and give recommendations for what to include in the methods and results section of a qualitative medical education research manuscript.

Qualitative research and scholarship in medical education encompass many topics, different learners and environments, and various educational techniques. Used on its own, a qualitative approach provides insights into how people interpret their experiences, uncovers meaning behind a phenomenon, or describes events that are unfamiliar or difficult to quantify. Qualitative data may be used to generate hypotheses and help make sense of how human experiences, social processes, and group interactions are connected.1 Thus, researchers in medical education who are focused on trying to understand what happened, why it happened, or how it happened should consider how a qualitative approach may help to answer their research questions.

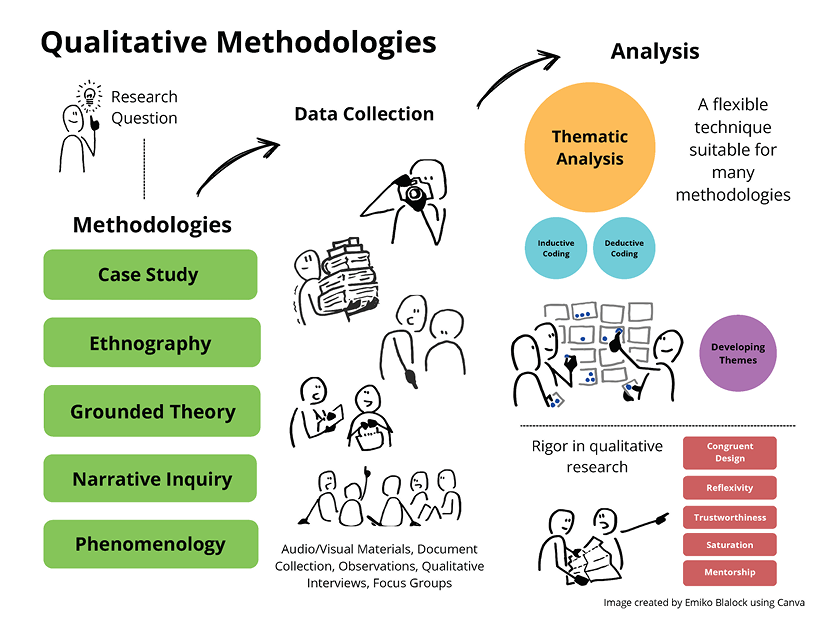

When contemplating a research question and designing a study, it is important to consider which qualitative methodology to use to answer the question. Methodology is a research plan of action and provides “an account of the rationale for the choice of methods and the particular forms in which the methods are employed.”2 A researcher’s views about the nature of knowledge and their concerns about what truth is influence both their research questions and the methodological approach that will best answer those questions.

This methodological brief reviews qualitative methodologies commonly used in medical education research. In this article, we do not discuss the role that ontologies (beliefs about what is real or true), epistemologies3 (understandings about the nature of knowing) or theories4 (explanations that help us understand the world) play in qualitative research.5–7 Rather, we offer an overview of five primary approaches to qualitative inquiry from across academic disciplines, then focus on their application and usefulness in medical education research. We then consider how to ensure a qualitative study has sufficient rigor and trustworthiness to be considered for publication, and offer tips, resources, and examples.

Developing the Research Question

Inquiry begins with curiosity, and often, a problem the researcher aims to solve. Examples include problems such as a shortage of primary care physicians, gaps in resident knowledge or skills, or the inequities of a hierarchical health care system. These problems form questions. Qualitative research helps to answer the “what,” “why,” and “how” questions to investigate these problems.1

Qualitative questions may explore a broad central phenomenon, eg, “Why is there a shortage of primary care physicians?” In defining an area of study, qualitative researchers examine a broad concept and develop more specific questions that are manageable in scope: “Why are so few primary care physicians in rural areas?” Or even more specific: “Why are so few women primary care physicians in rural areas?” Crafting research questions with broad inquiry, then sculpting these questions into more manageable sizes helps shape a realistic research design.8 A good qualitative question should be broad enough to be meaningful but focused enough to be answerable.

Methodology: Approaches to Qualitative Inquiry

Qualitative research is not a monolith. It is not defined by its methods, but rather its approach to science. Each research endeavor is guided by a methodology—a way to consider how to design a research study.9 Different qualitative methodologies have different histories, assumptions, traditions, and practical contemporary uses.10

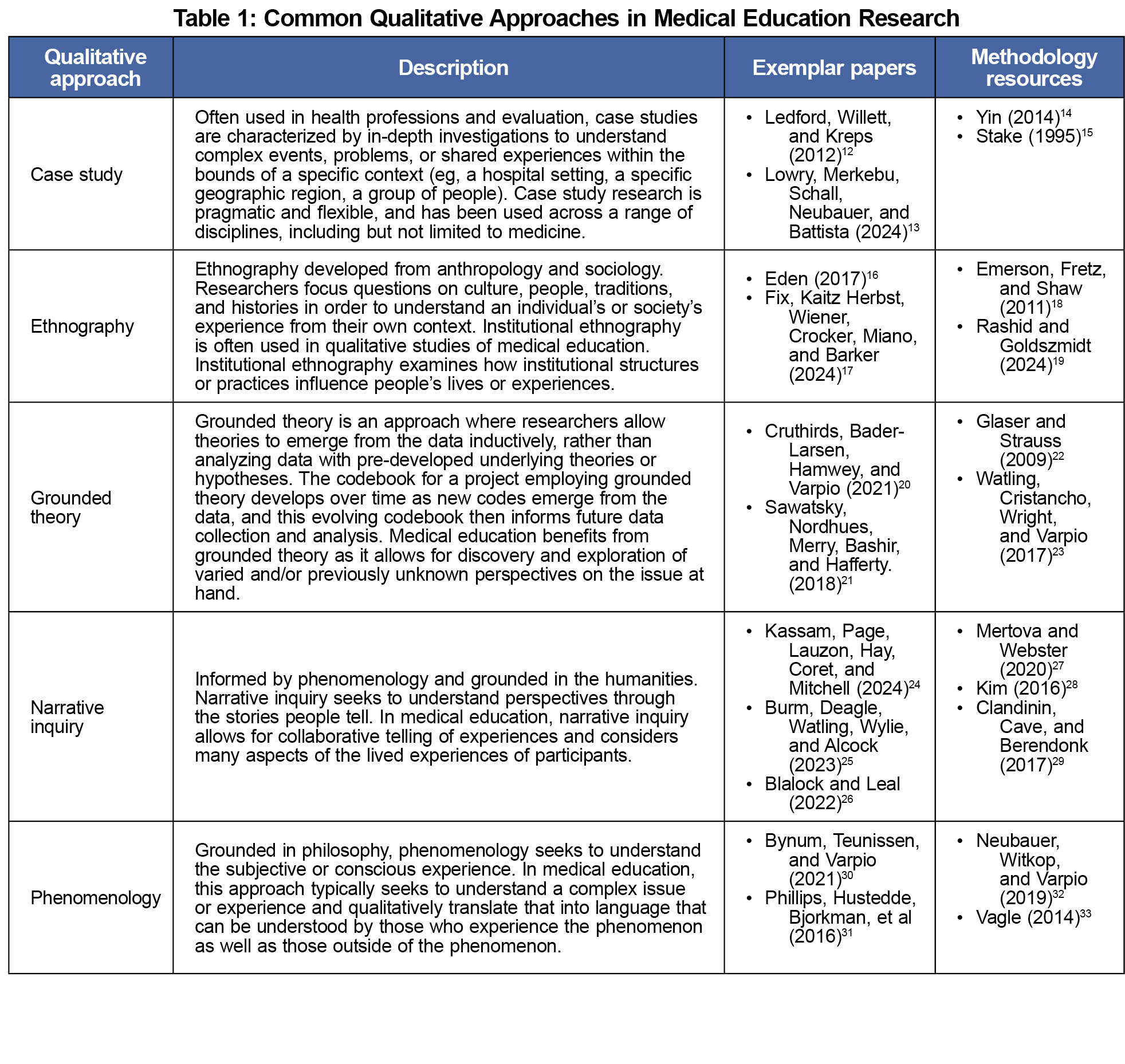

Five qualitative approaches are commonly used in medical education research, including case study, ethnography, grounded theory, narrative inquiry, and phenomenology.11 Each approach offers opportunities for researchers to answer complex questions in different ways. In Table 1 we provide a brief overview of each approach and how they could answer medical education research questions, list exemplar papers, and suggest in-depth methodology resources. These are basic definitions; we recommend that interested readers further explore the vast range of methodological approaches to qualitative inquiry, their underlying assumptions, and their history and use.

Data Collection Techniques

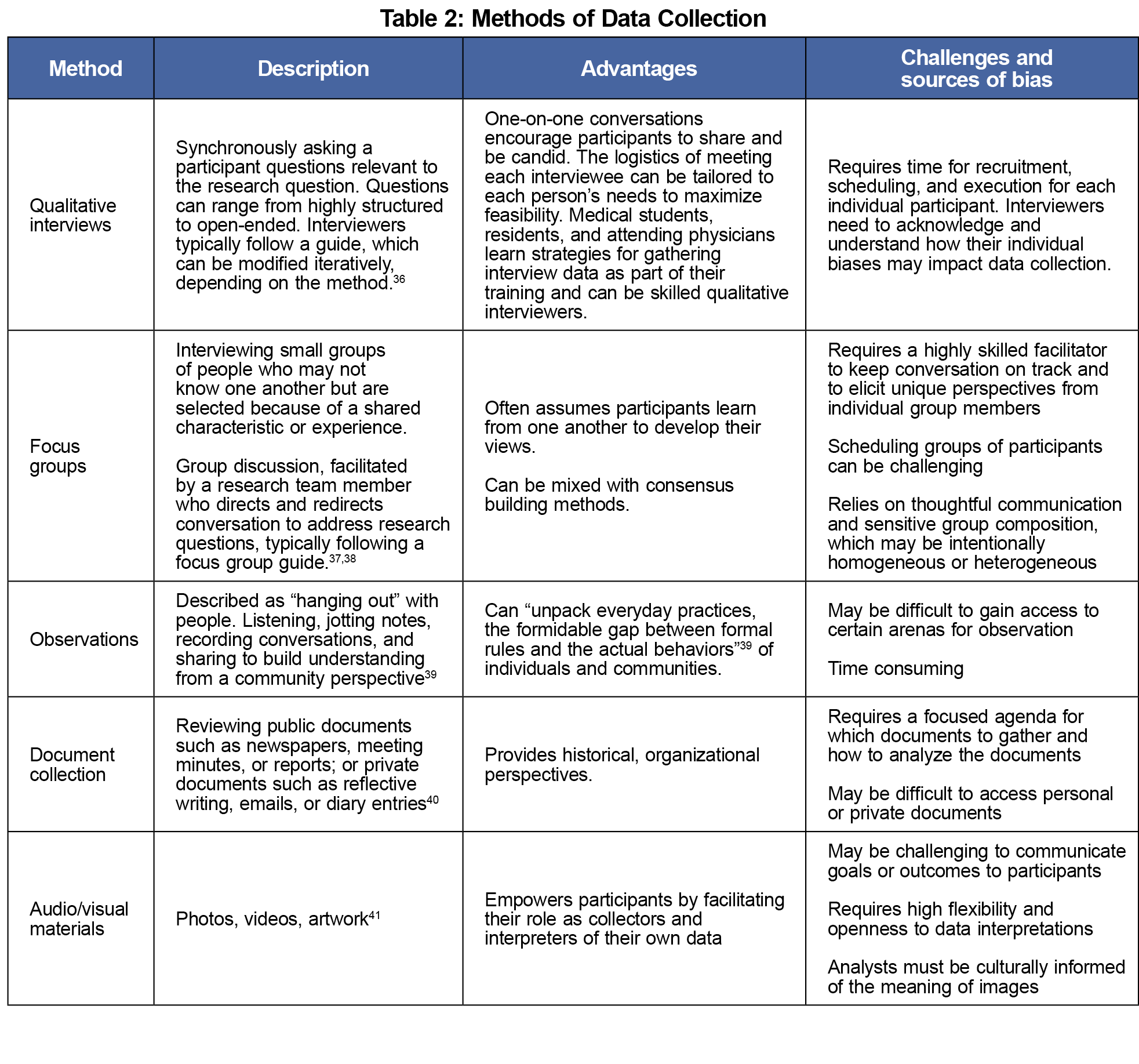

Methodology drives the practical design of a study. Although some qualitative methodologies are associated with specific forms of data collection techniques or methods, many types of data collection can be used across methodologies. In Table 2, we describe common types of data collection and their potential advantages, challenges, and sources of bias.

Qualitative data collection techniques enable the collection of complex, rich description that builds context and meaning. Researchers may be tempted to use responses to open-ended survey questions as data sources in medical education research. However, without careful attention to survey design, open-ended survey items can produce poor quality data.34,35 Survey respondents typically have limited time and energy for providing written information and may respond in a way that is designed to satisfy the surveyor. Surveys also do not allow for follow-up questioning and in-depth exploration, which is essential for rich understanding.

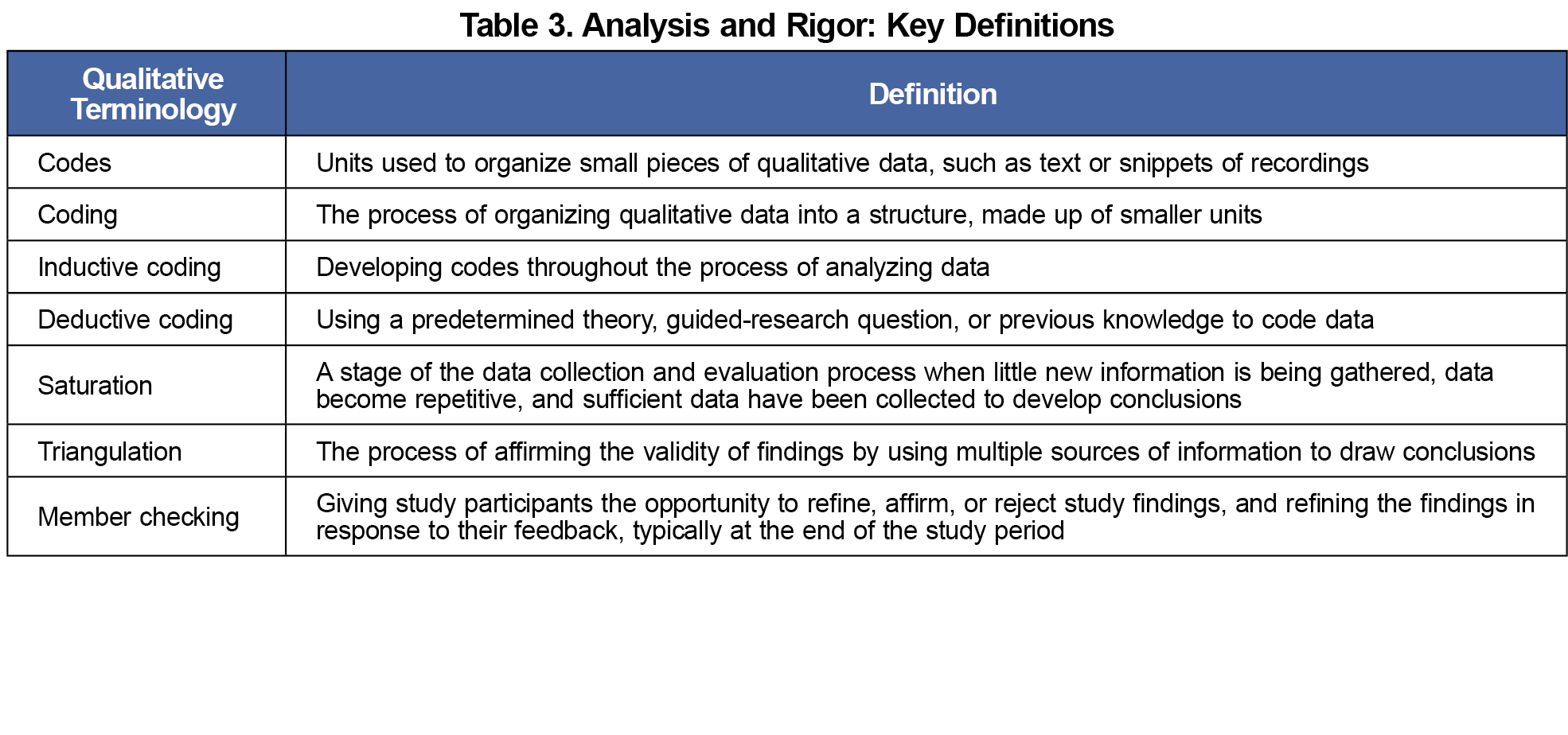

Although each of the five methodologies has a deep history of analysis processes, we focus here on thematic analysis (TA), a technique that is flexible enough to be suitable for many methodologies.42 TA is a “method for analyzing qualitative data that entails searching across a data set to identify, analyze, and report repeated patterns.”43 TA employs the process of coding, or the practice of labeling a single unit (such as a word, phrase, sentence or complete thought) with an identifying word or description. The coding process can be inductive or deductive. Codes are then grouped together, guided by the researcher, the methodology, the research question, and if being used, a theory. These groupings develop themes that together provide a deeper understanding of an aspect of a research question. Researchers often create codebooks to document and structure TA. A clear codebook can demonstrate rigor and replicability of a researcher’s methods.44 Key definitions related to TA are provided in Table 3.

Rigor in Qualitative Research: Taking Time to Build a High-Quality Study

Researchers can take specific steps during the design and analysis process to develop their study with rigor. This helps ensure that findings answer the research question truthfully and thoroughly and that the results can be trusted.45,46 Definitions relevant to rigor are given in Table 3.

- Congruent design: Each part of a qualitative study, from initial research questions, to methodology, to method, to theoretical framework, should work together as a congruent whole. “Good qualitative research is consistent; the question goes with the method which fits appropriate data collection, appropriate data handling, and appropriate analysis techniques.”47 This alignment, underpinning the research approach, is essential for rigorous qualitative research.48

- Reflexivity: Olmos-Vega and colleagues49 describe reflexivity as the continuous practices researchers apply to critique, appraise, and reflect on their own subjectivity during the research process. As qualitative researchers, we draw on our own experiences and beliefs about the world, which can shape interpretations of data. Describing our reflexive stance in the context of the study is essential to ensure transparency throughout the entire research process.44

- Trustworthiness and relationship building: Just as we are transparent with our own perspectives through reflexivity, as qualitative researchers we should also remain transparent and trustworthy in relation to those involved in the research. This includes participants, other researchers, and the audience for our work. Throughout the process our approach should be grounded in relationships and building trust.45 This includes open dialogue with other researchers during the analysis process as well as invitations for study participants to read the initial findings or even contribute to analysis, sometimes known as “member checking.”46 Triangulation is another technique that increases trustworthiness, when multiple sources of information point to the same conclusion. When presenting and publishing results, researchers should be transparent about their own biases and contextual experiences. These measures are unique to qualitative research and help to ensure rigor.47

- Saturation: Qualitative research typically involves gathering a range of individual perspectives about a problem. Researchers often reach a period of saturation in data collection, when they are hearing the same findings over and over again from multiple participants, and when participants are sharing little new information. Qualitative research typically does not begin with a predetermined sample size. Rather, researchers continue until saturation is reached.48 At the same time, researchers should acknowledge that their understanding of a problem can never be truly complete. The concept of saturation is practically useful, but it has been criticized and remains controversial.50

- Mentorship: Qualitative research is an advanced skill, and new researchers benefit from expert guidance and advice through working with a mentor or research team member experienced in qualitative research.51,52

Writing Results and Discussion: Telling a Qualitative Research Story

As with all empirical work, qualitative manuscripts describe the introduction, methods, results, and discussion of the study. While these sections mirror quantitative manuscripts familiar to medical education researchers, the content of each section slightly differs. In the introduction section of a qualitative manuscript, researchers describe the aim of the study within the context of what is known and not known about the topic. They also generally specify research questions. Qualitative methods sections are generally longer and far more detailed than in quantitative manuscripts. The methods section should clearly explain the theoretical underpinnings, methodological approach, data collection techniques, and analysis decisions. The rationale for choosing a specific approach will strengthen the credibility of findings. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) is a useful tool to help authors organize their methods section.53 The results section should describe the findings themselves, using summary language of the groupings or themes that are typically derived from the coding process. Results can be made more relevant to audiences by the addition of participant quotes or other examples from the data. In the discussion section, researchers synthesize findings, discuss the context of the broader literature, acknowledge limitations and potential biases, and consider opportunities for further research. Throughout the discussion, it is important to communicate how the qualitative approach contributed to the findings. Authors should avoid the temptation of comparing the rigor of qualitative inquiry to quantitative methods. The two approaches have two distinct purposes.

Qualitative research methods are important tools in medical education research, with specific methodologies and data collection techniques used to answer research questions. Ensuring methodological rigor is essential when developing a high-quality study, and the research manuscript should clearly describe the qualitative design, analysis, and results so that journal editors, peer reviewers, and readers can understand and trust the research process and its results. While this methodological brief gives an overview of qualitative methods for medical education research, there is a great breadth and depth to qualitative approaches, methodologies, and data collection techniques that we encourage medical education scholars to investigate. We hope that future methodological briefs will explore some of these topics.

Acknowledgments

Conflict Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ng SL, Baker L, Cristancho S, Kennedy TJ, Lingard L. Qualitative Research in Medical Education. In: Swanwick T, Forrest K, O’Brien BC, eds. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice.Wiley-Blackwell; 2018. doi:10.1002/9781119373780.ch29

- Crotty M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process.Sage Publications; 1998.

- Bunniss S, Kelly DR. Research paradigms in medical education research. Med Educ. 2010;44(4):358-366. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03611.x

- Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med. 2020;95(7):989-994. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075

- Kumar K, Roberts C, Finn GM, Chang YC. Using theory in health professions education research: a guide for early career researchers. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):601, s12909-022-03660-03669. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03660-9

- Cleland JA, Kuper A, O’Sullivan P. Go back to the original sources please! Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2024;29(5):1545-1548. doi:10.1007/s10459-024-10388-2

- Nimmon L, Paradis E, Schrewe B, Mylopoulos M. Integrating theory into qualitative medical education research. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):437-438. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00206.1

- Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches.4th ed. Sage Publications; 2014.

- Bourgeault IL, Dingwall R, De Vries RG, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research. Paperback edition. SAGE; 2013.

- Varpio L, Martimianakis MA, Mylopoulos M. Qualitative research methodologies: embracing methodological borrowing, shifting and importing. In: Cleland J, Durning SJ, eds. Researching Medical Education. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2022:115-125. doi:10.1002/9781119839446.ch11

- Glesne C. Becoming Qualitative Researchers: An Introduction.4th ed. Pearson; 2011.

- Ledford CJW, Willett KL, Kreps GL. Communicating immunization science: the genesis and evolution of the National Network for Immunization Information. J Health Commun. 2012;17(1):105-122. doi:10.1080/10810730.2011.585693

- Lowry LE, Merkebu J, Schall SE, Neubauer BE, Battista A; Picking Apart a Program Evaluation Committee. Picking apart a program evaluation committee: a multiple case study characterizing primary care residency program evaluation committee structure, program improvement, and outcomes. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e57439. doi:10.7759/cureus.57439

- Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods.5th ed. SAGE; 2014.

- Stake RE. The Art of Case Study Research.SAGE Publications; 1995.

- Eden AR. Breastfeeding support: from informal care work to professional health‐care work. Anthropol Work Rev. 2017;38(1):28-39. doi:10.1111/awr.12110

- Fix GM, Kaitz J, Herbst AN, et al. practical strategies for co-design: the case of engaging patients in developing patient-facing shared-decision making materials for lung cancer screening. J Patient Exp. 2024;11:23743735241252247. doi:10.1177/23743735241252247

- Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes.2nd ed. The University of Chicago Press; 2011. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226206868.001.0001

- Rashid M, Goldszmidt M. Critical ethnography: implications for medical education research and scholarship. Med Educ. 2024;58(10):1185-1191. doi:10.1111/medu.15401

- Cruthirds DF, Bader-Larsen KS, Hamwey M, Varpio L. Situational awareness: forecasting successful military medical teams. Mil Med. 2021;186(suppl 3):35-41. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab236

- Sawatsky AP, Nordhues HC, Merry SP, Bashir MU, Hafferty FW. Transformative learning and professional identity formation during international health electives: a qualitative study using grounded theory. Acad Med. 2018;93(9):1381-1390. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002230

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine; 2009.

- Watling C, Cristancho S, Wright S, Varpio L. Necessary groundwork: planning a strong grounded theory study. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(1):129-130. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00693.1

- Kassam A, Page S, Lauzon J, Hay R, Coret M, Mitchell I. Ethical issues in residency education related to the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative inquiry study. J Med Ethics. Published online June 26, 2024:jme-2023-108917. doi:10.1136/jme-2023-108917

- Burm S, Deagle S, Watling CJ, Wylie L, Alcock D. Navigating the burden of proof and responsibility: A narrative inquiry into Indigenous medical learners’ experiences. Med Educ. 2023;57(6):556-565. doi:10.1111/medu.15000

- Blalock AE, Leal DR. Redressing injustices: how women students enact agency in undergraduate medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023;28(3):741-758. doi:10.1007/s10459-022-10183-x

- Mertova P, Webster L. Using Narrative Inquiry as a Research Method: An Introduction to Critical Event Narrative Analysis in Research, Training and Professional Practice.2nd ed. Routledge; 2020.

- Kim JH. Understanding narrative inquiry: the crafting and analysis of stories as research. Sage. 2016. doi:10.4135/9781071802861

- Clandinin DJ, Cave MT, Berendonk C. Narrative inquiry: a relational research methodology for medical education. Med Educ. 2017;51(1):89-96. doi:10.1111/medu.13136

- Bynum WE IV, W Teunissen P, Varpio L. In the “Shadow of shame”: a phenomenological exploration of the nature of shame experiences in medical students. Acad Med. 2021;96(11S):S23-S30. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004261

- Phillips J, Hustedde C, Bjorkman S, et al. Rural women family physicians: strategies for successful work-life balance. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(3):244-251. doi:10.1370/afm.1931

- Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(2):90-97. doi:10.1007/S40037-019-0509-2

- Vagle MD. Crafting Phenomenological Research.Left Coast Press, Inc; 2014.

- Smyth JD, Dillman DA, Christian LM, Mcbride M. Open-Ended Questions in Web Surveys. Public Opin Q. 2009;73(2):325-337. doi:10.1093/poq/nfp029

- LaDonna KA, Taylor T, Lingard L. Why open-ended survey questions are unlikely to support rigorous qualitative insights. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):347-349. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002088

- McGrath C, Palmgren PJ, Liljedahl M. Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Med Teach. 2019;41(9):1002-1006. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497149

- Kidd PS, Parshall MB; Getting the Focus and the Group. Getting the focus and the group: enhancing analytical rigor in focus group research. Qual Health Res. 2000;10(3):293-308. doi:10.1177/104973200129118453

- Stalmeijer RE, Mcnaughton N, Van Mook WNKA. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Med Teach. 2014;36(11):923-939. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.917165

- Lareau A. Listening to People: A Practical Guide to Interviewing, Participant Observation, Data Analysis, and Writing It All Up.The University of Chicago Press; 2021. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226806600.001.0001

- Morgan H. Conducting a Qualitative Document Analysis. Qual Rep. 2022. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5044

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369-387. doi:10.1177/109019819702400309

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Sage. 2022.

- Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):846-854. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

- Roberts K, Dowell A, Nie JB. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):66. doi:10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y

- Tracy SJ. qualitative quality: eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual Inq. 2010;16(10):837-851. doi:10.1177/1077800410383121

- Wright KM, Gruppen LD, Kuo KW, et al. Assessing changes in the quality of quantitative health educations research: a perspective from communities of practice. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):227. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03301-1

- Richards L, Morse JM. Readme First for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods.Sage Publications, Inc; 2013, doi:10.4135/9781071909898.

- Teherani A, Martimianakis T, Stenfors-Hayes T, Wadhwa A, Varpio L. Choosing a qualitative research approach. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(4):669-670. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00414.1

- Olmos-Vega FM, Stalmeijer RE, Varpio L, Kahlke R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med Teach. 2022;45(3):1-11. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13(2):201-216. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Appleton C. “Critical friends”, feminism and integrity: a reflection on the use of critical friends as a research tool to support researcher integrity and reflexivity in qualitative research studies. Women Welf Educ. 2011;10:1-13.

- Tillmann-Healy LM. Friendship as method. Qual Inq. 2003;9(5):729-749. doi:10.1177/1077800403254894

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

There are no comments for this article.