Introduction: Family medicine contributes less scholarship and receives much less grant money than other specialties. Understanding when and how this disparity begins is a key step in addressing the gap in family medicine scholarship.

Methods: We analyzed data from the National Resident Matching Program’s (NRMP’s) Charting Outcomes in the Match (2016–2024) to compare family medicine applicants with applicants to other specialties (ie, internal medicine, pediatrics, and all specialties combined). We examined the mean number of research experiences and the number of presentations and publications applicants had completed prior to starting residency. Additionally, we analyzed NRMP surveys to evaluate the weight applicants placed on institutional research support when choosing a residency program and the weight program directors placed on applicants’ research experience.

Results: Family medicine applicants consistently reported fewer research experiences and presentations/publications than applicants to internal medicine, pediatrics, and all specialties combined. Osteopathic applicants showed the lowest research participation across all specialties we compared. Among other specialties, family medicine applicants placed less importance on programs’ research support, and family medicine residency program directors were less likely to consider research involvement when selecting applicants.

Conclusions: Our results suggest that family medicine’s underrepresentation in research begins during the residency application process or sooner. Increased involvement in family medicine research among medical students should be a key component of strategies for bridging the research gap.

A 2022 survey of physicians showed that only 7.4% of primary care specialists engaged in any research versus 26.5% in medical specialties, 18.6% in surgery, and 13.2% in other specialties.1 The origins of this relatively low engagement in research are multifactorial and may stem from long-standing structural and cultural barriers. Since the establishment of the specialty in 1969, family medicine has focused on patient care, partly in reaction to the perception of medicine’s dehumanization with increasing specialization.2 While this focus has been central to the specialty’s identity, it has contributed to a weaker research infrastructure and a reliance on findings from other disciplines.2,3 This trend has led to the specialty of family medicine receiving only 0.2% of National Institutes of Health grants over the last 5 years4 despite comprising over 12% of the US physician workforce.5

Understanding when and how this underrepresentation emerges is a key step in addressing it. This study examined medical students’ research engagement at the time of residency application. By comparing family medicine to other specialties, we aimed to identify how applicant characteristics and the attitudes of both applicants and program directors may contribute to this disparity. Differences in reported research involvement between applicants from MD-granting and DO-granting institutions also were assessed.

Data Sources

We analyzed data from the National Resident Matching Program’s (NMRP) Charting Outcomes in the Match6 for the years 2016, 2018, 2020, 2022, and 2024, because these years consistently divided data based on the same applicant characteristics. These characteristics included self-reported information from the applications of US MD, US DO, US international medical graduates (IMG), and non-US IMG medical school seniors and graduates, with data further broken down by the matched or unmatched status of the applicant. For each group, we extracted the mean number of research experiences and numbers of presentations and publications. We compared these characteristics across different applicant groups within family medicine (MD, DO) and across specialties (ie, internal medicine, pediatrics, and all specialties combined). To simplify the evaluation, we limited comparisons among specialties to the matched MD seniors that made up most of the incoming residency classes for the years studied.

We also extracted the percentage of students who reported considering the availability of research support when selecting and ranking residency programs from the NRMP applicant survey reports for the published years 2015, 2017, 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2023.7 Finally, we extracted the percentage of program directors who reported considering applicants’ “involvement and interest in research” (selected from a list of factors) when making interview and rank decisions from the NRMP program director survey reports for the years 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2021, and 2024.8 Survey data were compared across the specialties of family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, and all specialties combined.

Data Analysis

We compiled the extracted self-reported applicant data and survey data into a structured spreadsheet categorized by year, training background, and specialty. We plotted trends over time and differences across training background and specialties using line and bar graphs to visualize these comparisons. We reported data using descriptive statistics. Because the self-reported research data represented the entire population of applicants for the selected years rather than a sampled subset, inferential statistics were not applied. That is, we did not need to consider sampling variability in order to account for confidence intervals or hypothesis tests.

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board exempted this research from review.

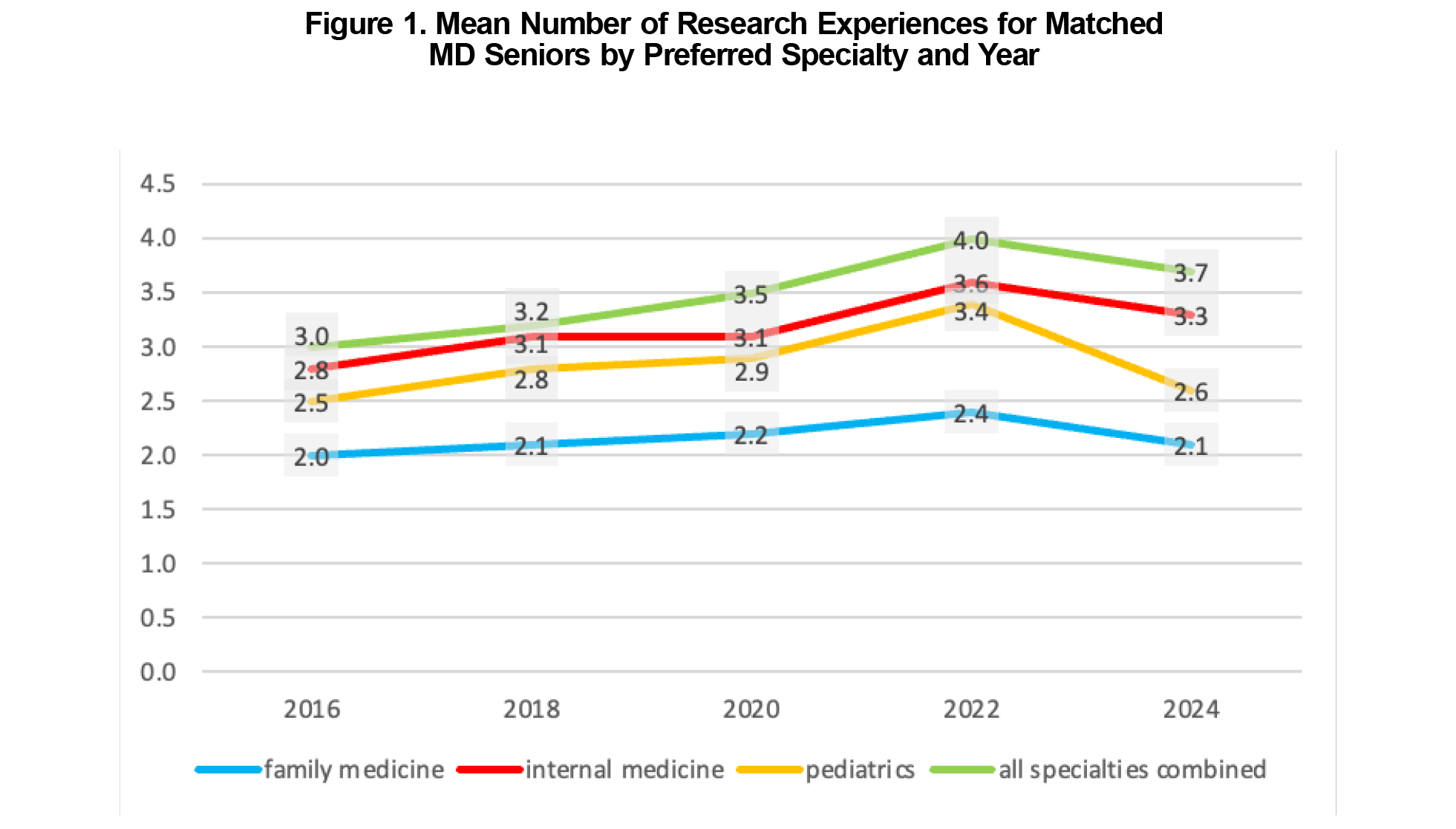

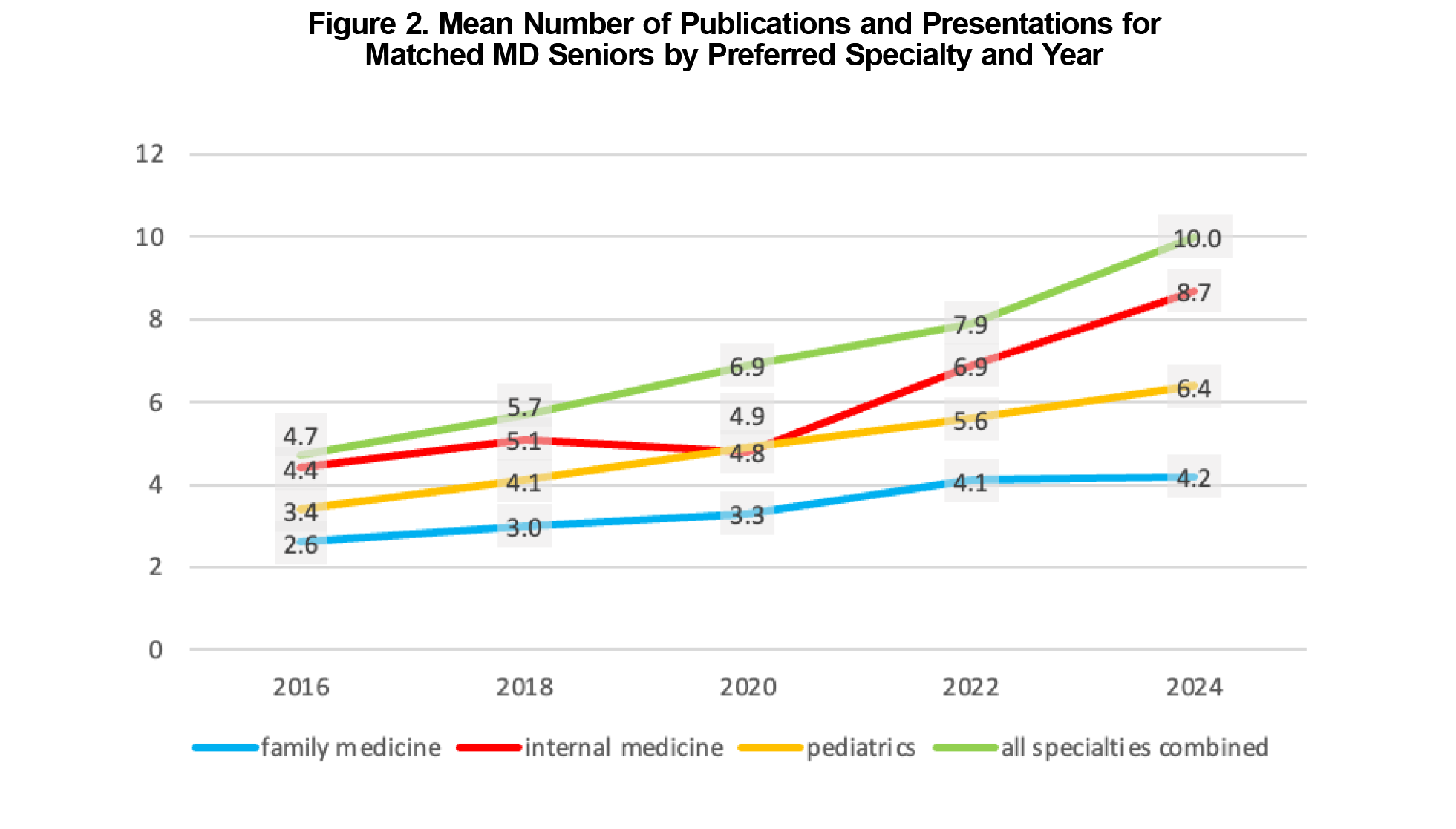

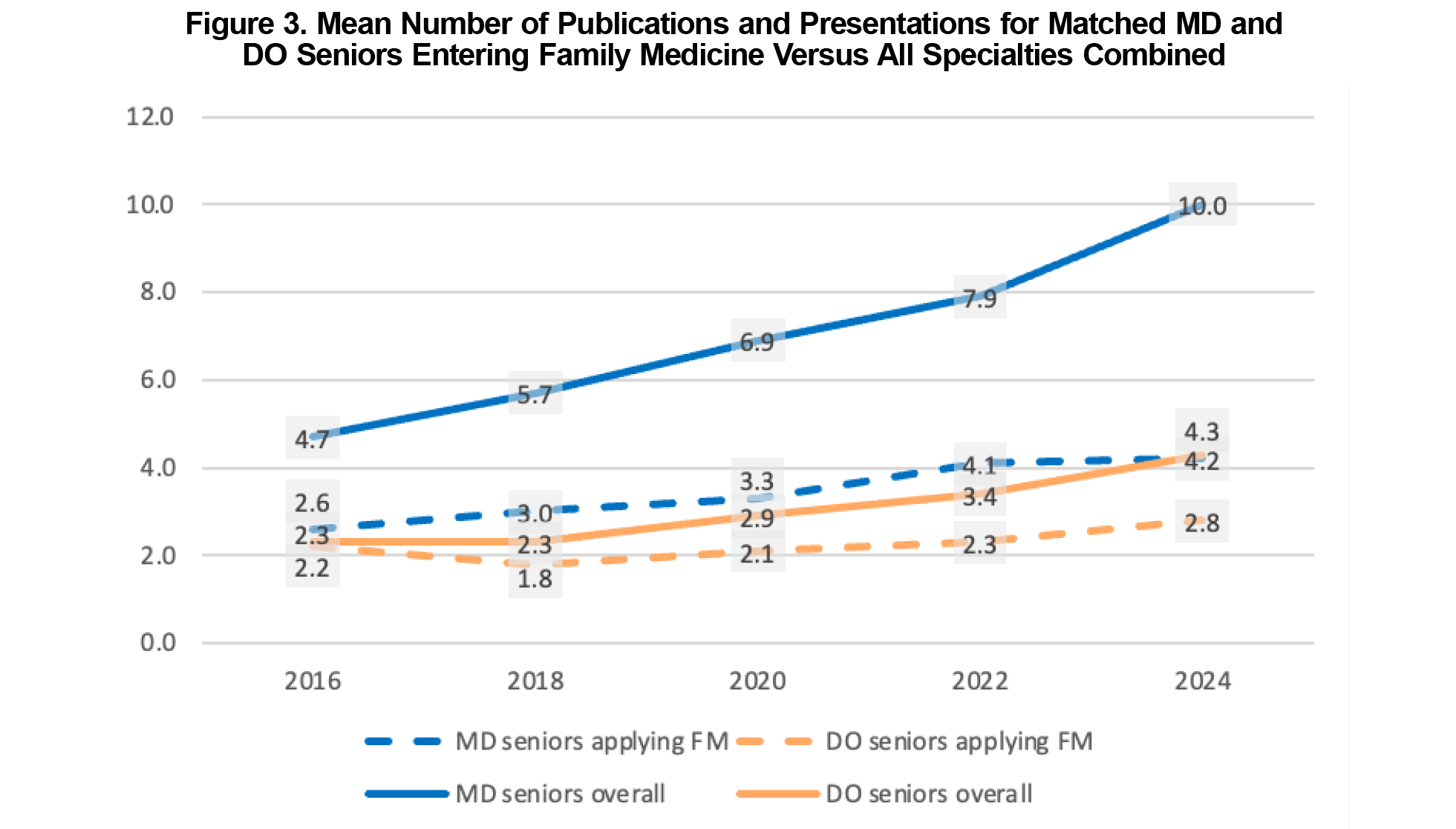

Medical students entering family medicine had fewer average research experiences than those entering internal medicine, pediatrics, and all specialties combined during each year of the analyzed period (Figure 1). They also reported fewer average publications and presentations than their counterparts in other specialties (Figure 2). The number of research experiences and publications increased in all groups over the observed period, though the rate of increase was slowest for family medicine applicants. Applicants matching into family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, and all specialties combined reported more publications than their DO counterparts (Figure 3).

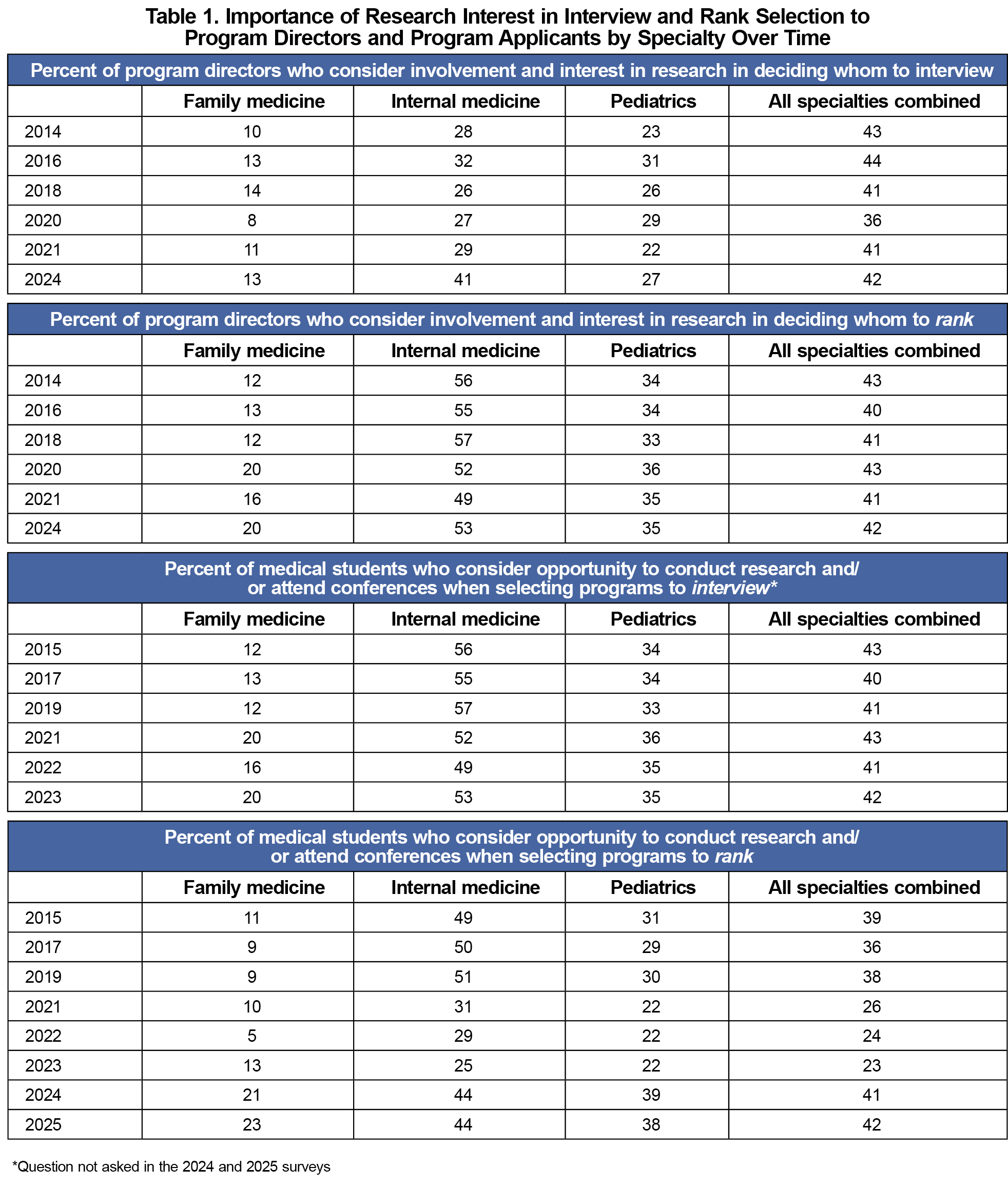

Family medicine residency program directors were less likely than program directors in internal medicine, pediatrics, and all specialties combined to report that they considered applicants’ “involvement and interest in research” in selecting whom to rank. Similarly, family medicine applicants were less likely to report that “opportunity and support to conduct research” was a factor in selecting a residency to rank than those applying to internal medicine, pediatrics, and all specialties combined (Table 1).

The data revealed that applicants to family medicine residencies reported fewer research experiences and less interest in access to research support than applicants to other specialties, and family medicine program directors reported less interest in applicants’ research experiences than their colleagues in other specialties. These findings suggest that residency selection practices play a role in family medicine’s underrepresentation in research. Additionally, osteopathic applicants to family medicine reported the lowest research of any group we evaluated, which may stem from a reduced research emphasis among osteopathic trainees.9

These conclusions were limited by a lack of data regarding other applicant characteristics, including age, gender, test scores, medical school grades, and intent to pursue fellowship, which may play a role in influencing our findings. Our inferences were limited to the evaluated years because we could not analyze past data and cannot know whether future data will continue to follow the observed trends. These factors limited our ability to distinguish whether any influence may stem from events such as the transition to a single graduate medical education accreditation system between 2015 and 202010 or the transition of the US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 exam to pass/fail in 2022.11 Another limitation involved the variability in how applicants self-reported research experiences within the constrained categories of the Electronic Residency Application Service.

Our findings suggest that the limited research exposure of family medicine applicants may contribute to family medicine’s ongoing lag behind other specialties in research involvement. While ongoing efforts to build research capacity within family medicine are helping to correct the existing deficit in research expertise,12-14 increased involvement in family medicine research among medical students should be a key component of strategies for bridging the research gap.9,15,16

References

- Browne A. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians engaged in research in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(9):e2433140. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.33140

- Gotler RS. Unfinished business: the role of research in family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):70-76. doi:10.1370/afm.2323

- Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228-242. doi:10.1002/cncr.23157

- Huffstetler A, Byun H, Jabbarpour Y. Family medicine research is not a federal priority. Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(6):541B-541C.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Active Physicians in the Largest Specialties by Major Professional Activity. AAMC; 2021. Accessed December 10, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-largest-specialties-major-professional-activity-2021

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting OutcomesTM: Characteristics of Applicants Who Match to Their Preferred Specialty. NRMP; August 20, 2024. Accessed December 8, 2024. https://www.nrmp.org/match-data/2024/08/charting-outcomes-characteristics-of-applicants-who-match-to-their-preferred-specialty-2

- National Resident Matching Program. 2024 Charting OutcomesTM: Applicant Survey Report. NRMP; September 3, 2024. Accessed December 10, 2024.https://www.nrmp.org/about/news/2024/09/2024-charting-outcomes-applicant-survey-report-now-available

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting OutcomesTM: Program Director Survey Results, 2024 Main Residency Match®. NRMP; August 8, 2024. Accessed December 10, 2024.https://www.nrmp.org/match-data/2024/08/charting-outcomes-program-director-survey-results-main-residency-match

- Stacey SK, Seidenberg PH. Osteopathic research in family medicine. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(suppl2):S59-S63. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2023.230482R1

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. History of the transition to a single GME accreditation system. Accessed June 10, 2025. https://www.acgme.org/about/transition-to-a-single-gme-accreditation-system-history

- United States Medical Licensing Examination. USMLE Step 1 transition to pass/fail score reporting. USMLE; September 15, 2021. Accessed June 10, 2025. https://www.usmle.org/usmle-step-1-transition-passfail-only-score-reporting

- Nease DE Jr, Westfall JM, Wilson E. Practice-based research networks: asphalt on the blue highways of primary care research. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(suppl2):S129-S132. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2023.230493R1

- Stacey SK, Seidenberg PH, Meadows LM, Schneider D, Ewigman B. Building research capacity (BRC): purposes, components, and activities to date. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(suppl2):S96-S101. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2024.240033R1

- Tallia AF, Ferrante JM, Hill D, et al. Building family medicine research through community engagement: leveraging federal awards to develop infrastructure. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(suppl2):S133-S137. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2024.240007R1

- Beinhoff P, Prunuske J, Phillips JP, et al. Associations of the informal curriculum and student perceptions of research with family medicine career choice. Fam Med. 2023;55(4):233-237. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.862044

- Ringwald B, Gilfoyle M, Bosworth T, et al. Putting trainees at the center of the family medicine research workforce of tomorrow. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024;37(Suppl2):S30-S34. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2023.230499R1

There are no comments for this article.