Introduction: Physicians’ biased attitudes toward people who use drugs (PWUD) can impact the care they deliver. Despite recommendations from national organizations, treatment of substance use disorders and harm reduction are often absent from medical school curricula. This absence may influence how medical students, as future physicians, perceive PWUD and therefore, impact the care they provide. Our study aimed to assess medical students’ attitudes and, to a lesser extent, knowledge and self-confidence regarding substance use and harm reduction by identifying factors associated with positive beliefs about PWUD and students’ self-confidence in managing their care.

Methods: We emailed an optional, anonymous Qualtrics survey of multiple-choice and Likert-type questions to all students at Florida International University’s Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine (FIU HWCOM). The survey included demographics, prior exposure to PWUD, attitudes regarding drug acceptability, and substance use treatment.

Results: Of 496 medical students who received the survey, 172 (34.7%) responded to all questions. The primary outcome was attitudes, while secondary outcomes were knowledge and self-confidence. Clinical students reported significantly more positive attitudes toward PWUD compared with preclinical students. Similarly, students with personal or professional experience with PWUD had more positive attitudes and reported increased knowledge about substance use and treatment.

Conclusion: Our findings show that exposure to PWUD may positively impact medical students’ attitudes and knowledge in caring for patients with substance use disorders. However, gaps in knowledge and self-confidence persist, particularly in preclinical years. Introducing harm reduction and substance use topics earlier in the curriculum may address knowledge gaps, shift attitudes, and ultimately equip students to provide equitable care.

According to the Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration, in 2023, 54.2 million people needed substance use treatment, and drug use cost the United States $151.4 billion.1 Recognizing this, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education and Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommend including clinical education on substance use disorders (SUD) and treatments in medical school curricula.2 However, medical education on these topics remains sparse, with programs averaging only 12 hours of curricular time on substance use, which may limit the impact of the delivered content.2-3

Stigma among health care providers has been found to affect patient satisfaction and self-esteem, leading to suboptimal treatment outcomes.4 Negative beliefs and attitudes likely contribute to medical professionals’ stigmatization of people who use drugs (PWUD), leading to substandard care, such as the underutilization of medications for opioid use disorders (MOUD), and in some case studies, punishment of already vulnerable populations. Data demonstrate that medical students are particularly likely to hold negative attitudes toward PWUD. Due to the implications for patient care and outcomes, evaluating attitudes and intervening as indicated become a critical aspects of addressing barriers to care.5-8

Importantly, research has shown that didactic education on substance use and harm reduction positively affects medical students’ knowledge of these topics.7 Therefore, integrating these topics into undergraduate medical education curricula is crucial for creating physicians who provide compassionate and competent care.9,10 Considering that attitudes in addition to knowledge influence clinical practice, a better understanding of medical student attitudes toward PWUD and the factors that influence those attitudes can inform educational interventions with the goal of ultimately improving outcomes.8

At the time of this study, curricular education on SUD at our South Florida medical school was limited to diagnostic criteria and discussion of abstinence. Noting these limitations, the primary aim of our study was to assess medical students’ attitudes and factors associated with such attitudes toward PWUD. Secondarily, we sought to assess knowledge and confidence managing SUD.

We sent an optional, anonymous Qualtrics survey consisting of 15 multiple-choice and Likert-type questions via email list serv to all Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine students between August 1, 2023 and October 31, 2023 (see Appendix 1). This study was approved by the Florida International University Institutional Review Board.

Questions assessed demographic data, including education level, political affiliation, race, and ethnicity. Prior personal and professional experience and attitudes towards PWUD, as well as knowledge and confidence in treating SUD were assessed.

The questions were stratified into the primary domain, attitudes (Appendix 1: statements 2, 4, and 8); and secondary domains, perceived self-confidence (Appendix 1: statement 5), and knowledge (Appendix 1: statements 6 and 7). Statements 1 and 3 were excluded from analysis because they assessed overlapping domains (eg, attitudes and self-confidence).

Analytical Methods

We used R programming language version 4.3.1 to analyze quantitative data. Five submissions were excluded for having multiple unanswered questions. Three submissions had no responses, and two submissions lacked responses regarding attitudes. We conducted descriptive analyses, including univariate frequencies. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to analyze factors associated with more positive attitudes, knowledge, and self-confidence.

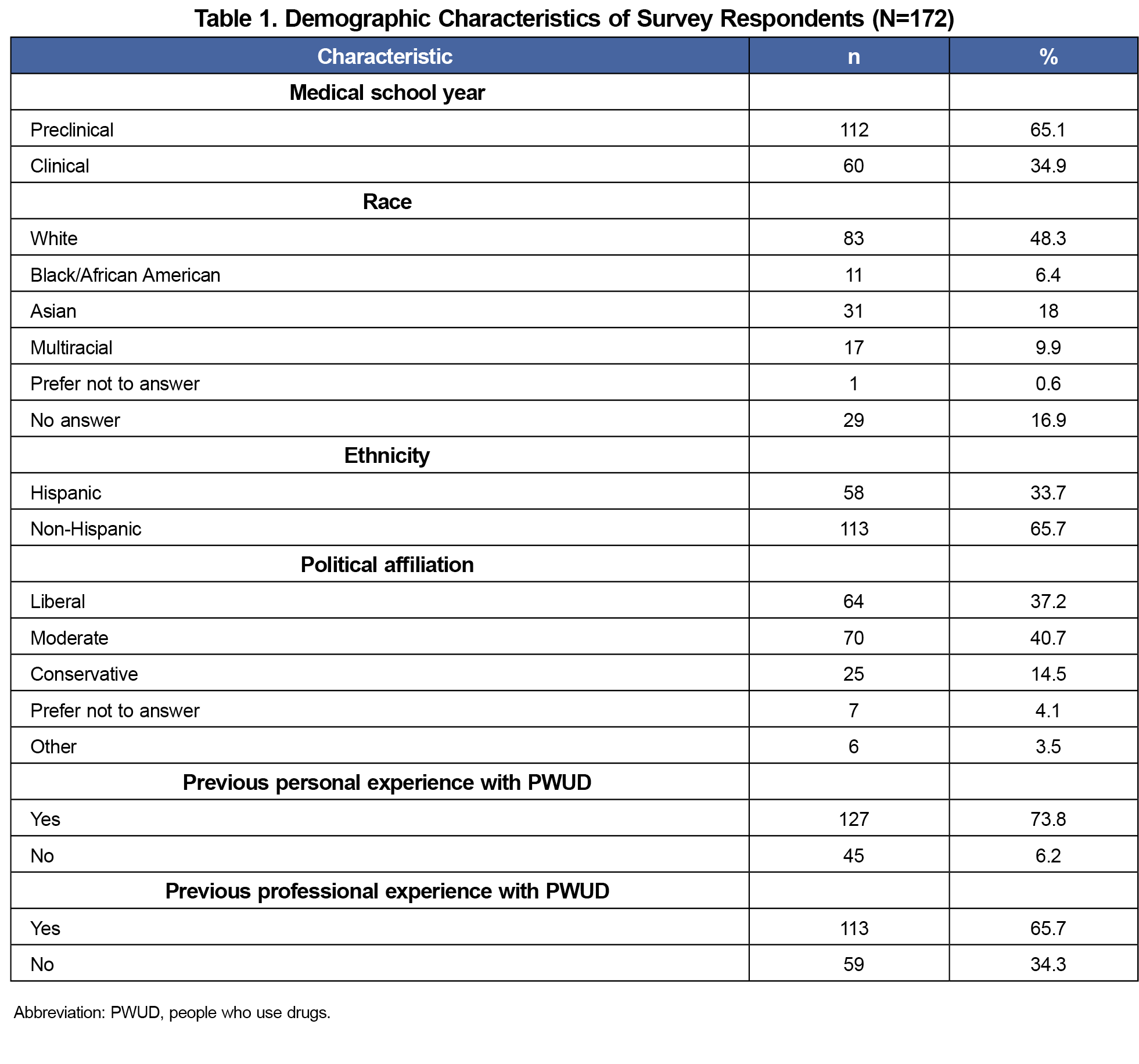

Of 496 medical students, 172 (34.7%) responded to all questions on the survey and were included in the analysis. Most students (65%) were in their preclinical years. Forty-eight percent identified as White and 33.7% as Hispanic. Most reported previous personal (74%) or professional (66%) experience with PWUD (Table 1).

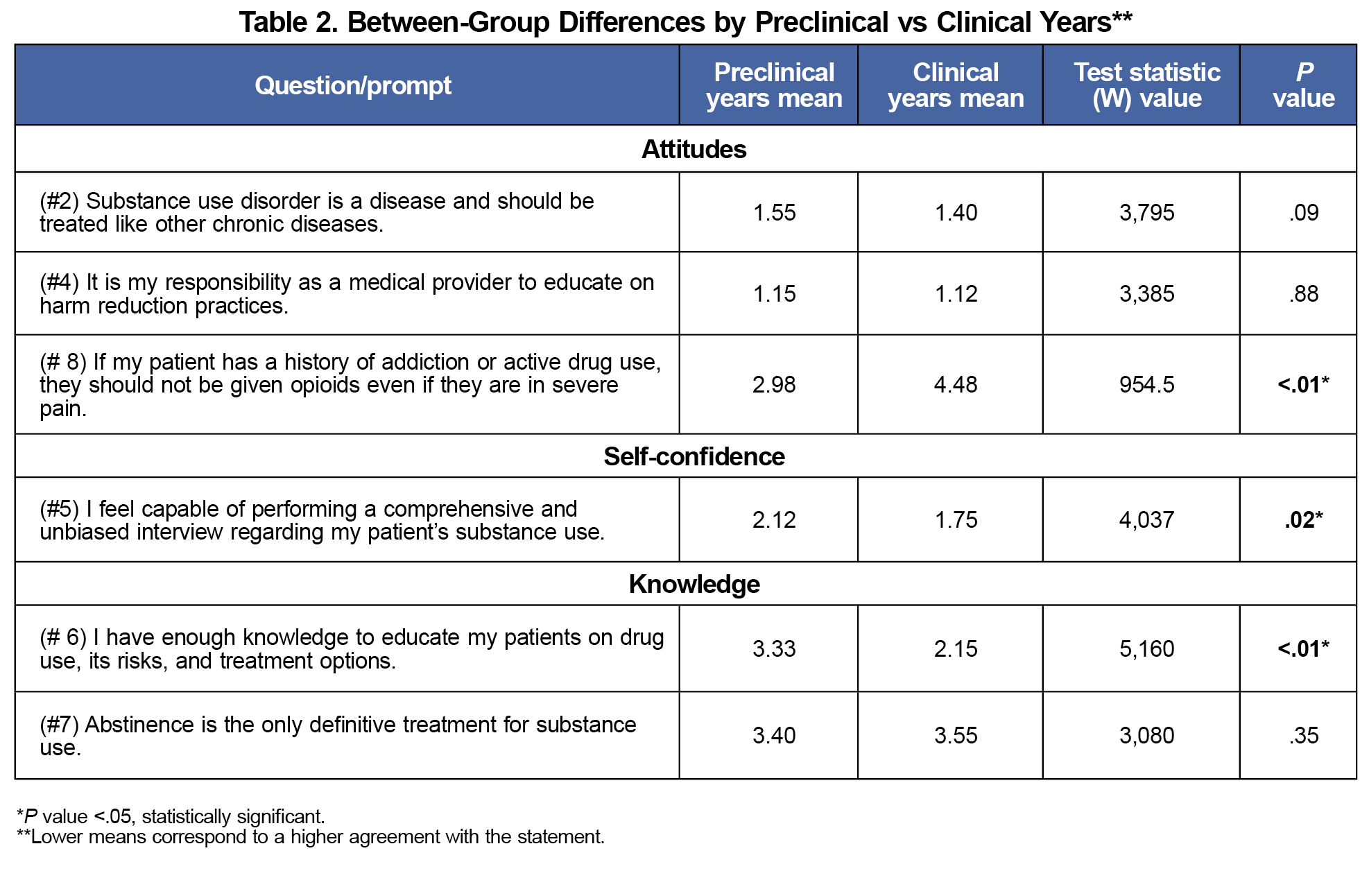

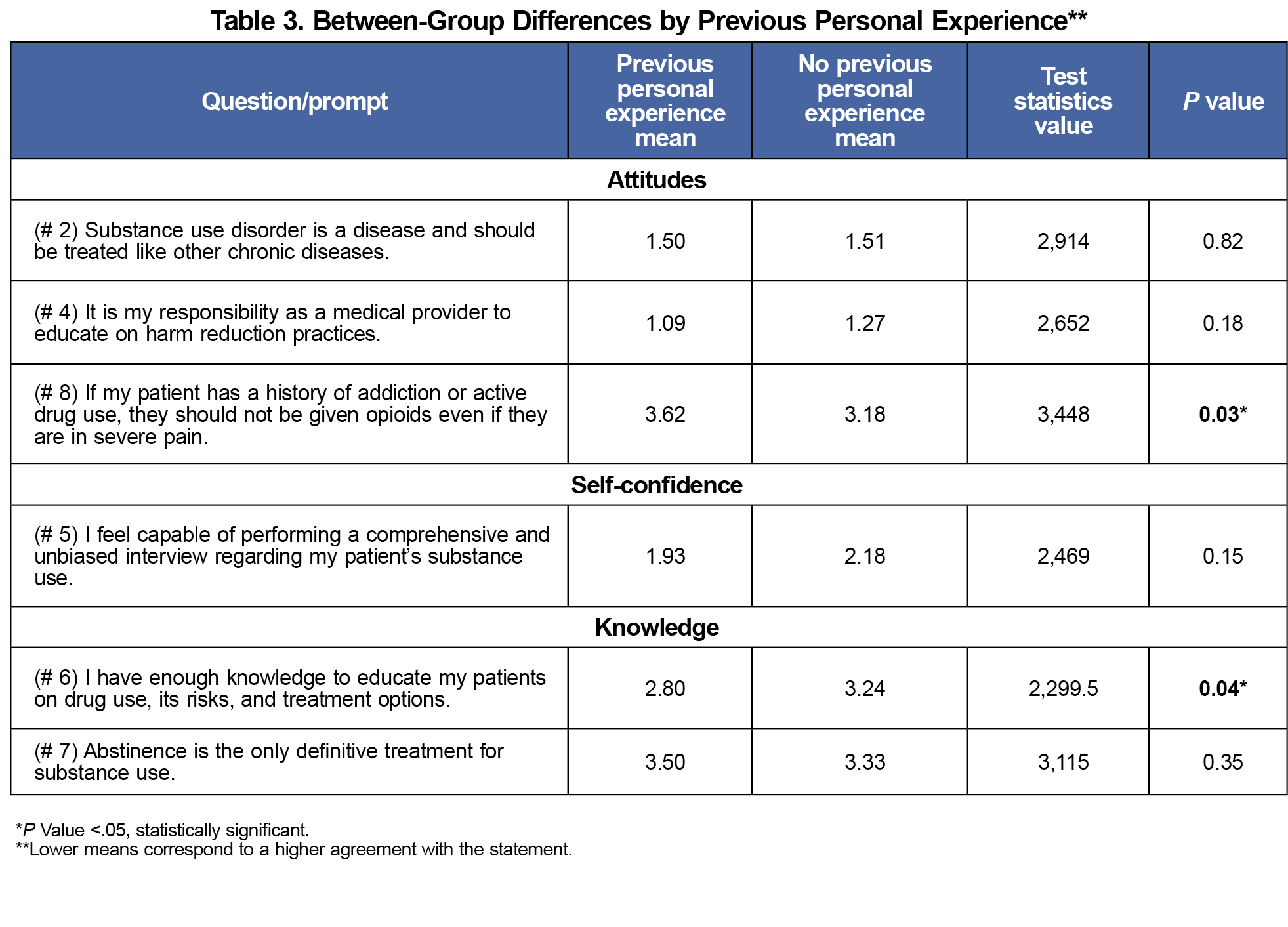

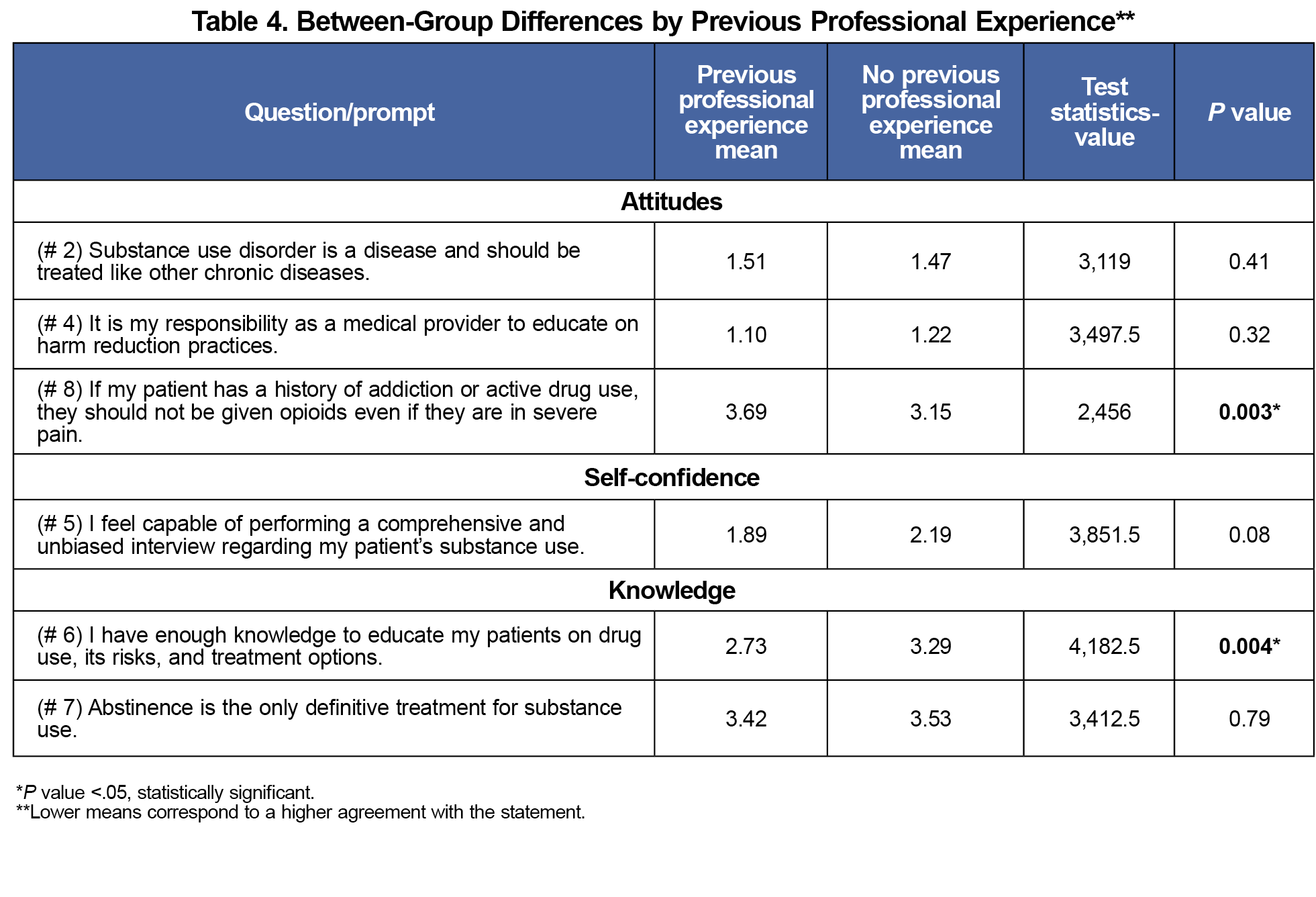

For the primary outcome, over 90% reported positive attitudes (Appendix 1: statements 2 and 4) for statements that legitimized SUD as a chronic disease and acknowledged a provider's responsibility to endorse harm reduction. However, only approximately half (55%) of students responded positively regarding opioid use for pain control in active users. Preclinical medical students had significantly more negative attitudes (W=955, P<.01, Table 2). Those with previous personal experience with PWUD had more positive attitudes regarding opioid use for pain control (W= 3448, P=.03) as well as those with previous professional experience compared to those without (W= 2456, P=.003).

Additionally, preclinical students reported less knowledge on educating their patients on the risks of drug-use and treatment options (W=5160, P<.01). Students with previous personal experience with PWUD reported greater knowledge of treatment options (W=2299.5, P=.04). Similarly, previous professional experience was associated with higher reported knowledge of drug use and treatment options (W= 4,182.5, P=.004).

Regarding perceived confidence, only 50% of respondents felt confident in their knowledge of substance use and treatment. There was no significant difference in reported self-confidence in obtaining a history from a PWUD between students with and without previous personal experience (W= 2,469, P=.15, Table 3). Finally, there was no difference in self-confidence in ability to work with PWUD between students with and without previous professional experience with this population (W=3,851.5, P=.08, Table 4).

Political affiliation was not statistically significant for any findings; however, students who identified as conservative were more likely to favor the belief that abstinence is the only treatment option.

Our findings demonstrate that increased exposure to PWUD is associated with more positive attitudes. There are significant differences between preclinical and clinical year students’ attitudes toward PWUD and reported comfort level completing a comprehensive and unbiased interview regarding substance use. These findings suggest that experience working with PWUD could mitigate negative attitudes toward and foster comfort in working with this population. Our findings align with studies that have shown differences in stigmatization correlating with the level of exposure to PWUD, supporting the idea that it is important for preclinical students to be exposed to PWUD. Learning opportunities focused on working with PWUD increases awareness, sensitivity, and empathy for this population.12

Secondarily, exposure was also associated with increased perceived knowledge. In our survey, preclinical students reported less confidence in educating patients on drug use, its risks, and treatment options for SUD, thereby suggesting a curricular gap. However, it is well known that perceived confidence may not reflect true competence; therefore, future studies should objectively evaluate student performance through clinical evaluations or observed structure clinical evaluations (OSCEs).13

The AAMC recommends 8 hours of instruction on the treatment and management of opioid and other SUD without significant guidance on breadth, depth, or evaluation of curriculum, including whether harm reduction should be an included topic.13 Our results showed uniformity in students’ recognition that SUD, in general, is a medical condition. However, larger differences in responses were noted when students were asked to assess specific scenarios, like opioid prescriptions for users in pain, suggesting attitudes were more positive in theory than when in practice.

Limitations of this study include self-reporting bias and a limited sample size at this single institution, thereby limiting external validity. Additionally, self-perceived notions of knowledge and self-confidence may not accurately reflect actual knowledge or skills.13 Nonetheless, these thoughts and perceptions can help inform curricular interventions aimed at increasing comfort in engaging with PWUD. Previous exposure to PWUD was assessed in a dichotomous question, in which the extent of exposure cannot be assessed, thus limiting the ability to compare the amount of previous exposure and differences between groups. Some of the statements in the survey may also have assumed skills beyond the training of a medical student, such as performing an unbiased interview about substance use. Future studies should compare specific educational interventions in preclinical and clinical years and objectively assess student knowledge and skills.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented at the Florida Harm Reduction Conference, November 6-8, 2023, i Miami, Florida.

Conflict Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP24-07-021, NSDUH Series H-59). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2024. Accessed October 24, 2025. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-annual-national-report

- Kothari D, Gourevitch MN, Lee JD, et al. Undergraduate medical education in substance abuse: a review of the quality of the literature. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):98-112. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff92cf

- Ram A, Chisolm MS. The time is now: improving substance abuse training in medical schools. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(3):454-460. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0314-0

- Fong C, Mateu-Gelabert P, Ciervo C, et al. Medical provider stigma experienced by people who use drugs (MPS-PWUD): development and validation of a scale among people who currently inject drugs in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108589. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108589

- Brown AR. Health professionals’ attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder. Subst Abus. 2022;43(1):598-614. doi:10.1080/08897077.2021.1975872

- Richelle L, Dramaix-Wilmet M, Roland M, Kacenelenbogen N. Factors influencing medical students' attitudes towards substance use during pregnancy. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):335. Published 2022 May 2. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03394-8

- Feeley RJ, Moore DT, Wilkins K, Fuehrlein B. A focused addiction curriculum and its impact on student knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in the treatment of patients with substance use. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(2):304-308. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0771-8

- van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018

- Muzyk A, Smothers ZPW, Akrobetu D, et al. substance use disorder education in medical schools: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1825-1834. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002883

- Jawa R, Saravanan N, Burrowes SAB, Demers L. A call for training graduate medical students on harm reduction for people who inject drugs. Subst Abus. 2021;42(3):266-268. doi:10.1080/08897077.2021.1932697

- Kabli N, Liu B, Seifert T, Arnot MI. Effects of academic service learning in drug misuse and addiction on students’ learning preferences and attitudes toward harm reduction. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(3):63. doi:10.5688/ajpe77363

- Magnan E, Weyrich M, Miller M, et al. Stigma against patients with substance use disorders among health care professionals and trainees and stigma-reducing interventions: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2024;99(2):221-231. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005467

- Morley CP. Moving on from self-assessment. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2024;8:5. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2024.624901

There are no comments for this article.