Introduction: The Age-Friendly Student Senior Connection (AFSSC) is a graduate-level interprofessional (IP) health student service-learning effort launched early in the COVID-19 pandemic to connect older adults to students providing both social support and health resources to seniors through dyad phone calls between IP health students and community-dwelling elderly. Our study aimed to examine changes in students’ attitudes toward older adults after participation in the program.

Methods: IP graduate health students were paired with community-dwelling older adults to engage in weekly remote interactions over a 6 to10-week period. Students completed a postparticipation online survey that included an open-ended qualitative question about program impact on challenging or reinforcing their preconceived notions about older adults. We used descriptive statistics to characterize participants, and conducted thematic content analysis to inductively explore student-reported lessons learned.

Results: Students reported that program participation challenged their preconceived notions of older adults and aging. Commonly identified themes included resilience, continued activity, and social interactions among older adults, observations about health conditions, and the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults.

Conclusions: Study findings demonstrate the positive effects of the AFSSC on health professions students' attitudes toward and perceptions of older adults. Student participation in intergenerational service-learning programs may reduce negative elderly stereotypes by challenging preconceived notions and improving student understanding and appreciation of older adults.

Primary care involves caring for older adults. Geriatrics training for interprofessional (IP) primary care teams is vital and the current workforce is insufficient to meet these needs. 1 A systematic literature review suggests that medical students view elderly patients as complex and intimidating.2 Increased knowledge about older adults may improve health professionals’ ageism, improving their care. 3

Health professions students who were initially intimidated by older adult patients found the challenge “rewarding” after receiving elderly-care training. Improved student attitudes correlated with greater geriatric interest. 2 Multiple health science programs demonstrated favorable student attitudes after working directly with older adults. 4-9

Few studies document IP health students’ older adult virtual/audio interactions.10-11 The studies reported have been almost exclusively with medical students.12-14 The COVID-19 pandemic limited in-person geriatric health visits.15 To address elderly loneliness and social isolation, the Keck School of Medicine of USC (KSOM) Family Medicine Department launched the Age-Friendly Student Senior Connection (AFSSC), a graduate, interprofessional (IP) health professions student effort to: (1) provide social support to community-dwelling older adults, (2) create elderly longitudinal relationships, and (3) introduce students to geriatric health/resource needs.13 This study examined changes in health professions students’ elderly attitudes after AFSSC.

Participants

Participants were master’s and doctoral-level IP students from the University of Southern California (USC), enrolled in medicine, dentistry, physician assistant, occupational therapy, physical therapy, social work, pharmacy, or psychology. In spring 2020, program participants were recruited through class-wide emails and student interest group list servs to “connect USC health professions students with older adults.” Recruited students watched prerecorded video trainings on older adult communication (48 minutes).

Intervention

Each student was paired with an older adult, recruited from the community, who was at least 65 years old, without documented cognitive impairment, and spoke English. The dyads communicated remotely via phone/videoconferencing for at least 30 minutes weekly, but not more than 90 minutes, for 6-10 weeks. Duration of interactions varied based on participants’ availability. Students attended weekly Zoom debrief sessions discussing their experiences with an IP geriatrics faculty facilitator, received weekly communication tips, and utilized a senior referral database. Students did not dispense medical advice; rather, they encouraged their partners to contact their primary care providers for health concerns. Trained faculty facilitators were on call for emergencies.Detailed program information has been previously published.17 While not measured, dyads were given the option to stay in contact poststudy.

Measurements

Students completed a program registration form, providing personal information and their participation goals. This study received a USC Institutional Review Board approval (HS-16-00633). After the program’s conclusion, students received a quantitative and open-ended qualitative question survey17-21 to complete on their experience with their older adults. They also provided proxy older adult partner demographic information. We analyzed one qualitative, open-ended question that asked, “What did you learn that contradicted and/or reinforced your preconceived notions about older adults?” in this study. Additional data have been previously reported.17

Analysis

Descriptive statistics described participant demographic characteristics and reasons for program participation. Two coders (D.C. and J.Y.C) independently conducted thematic content analysis of the open-ended survey question querying student change in perception, inductively identifying commonalities in survey responses. The coders discussed and resolved interrater coding differences to achieve a 95% concordance rate.

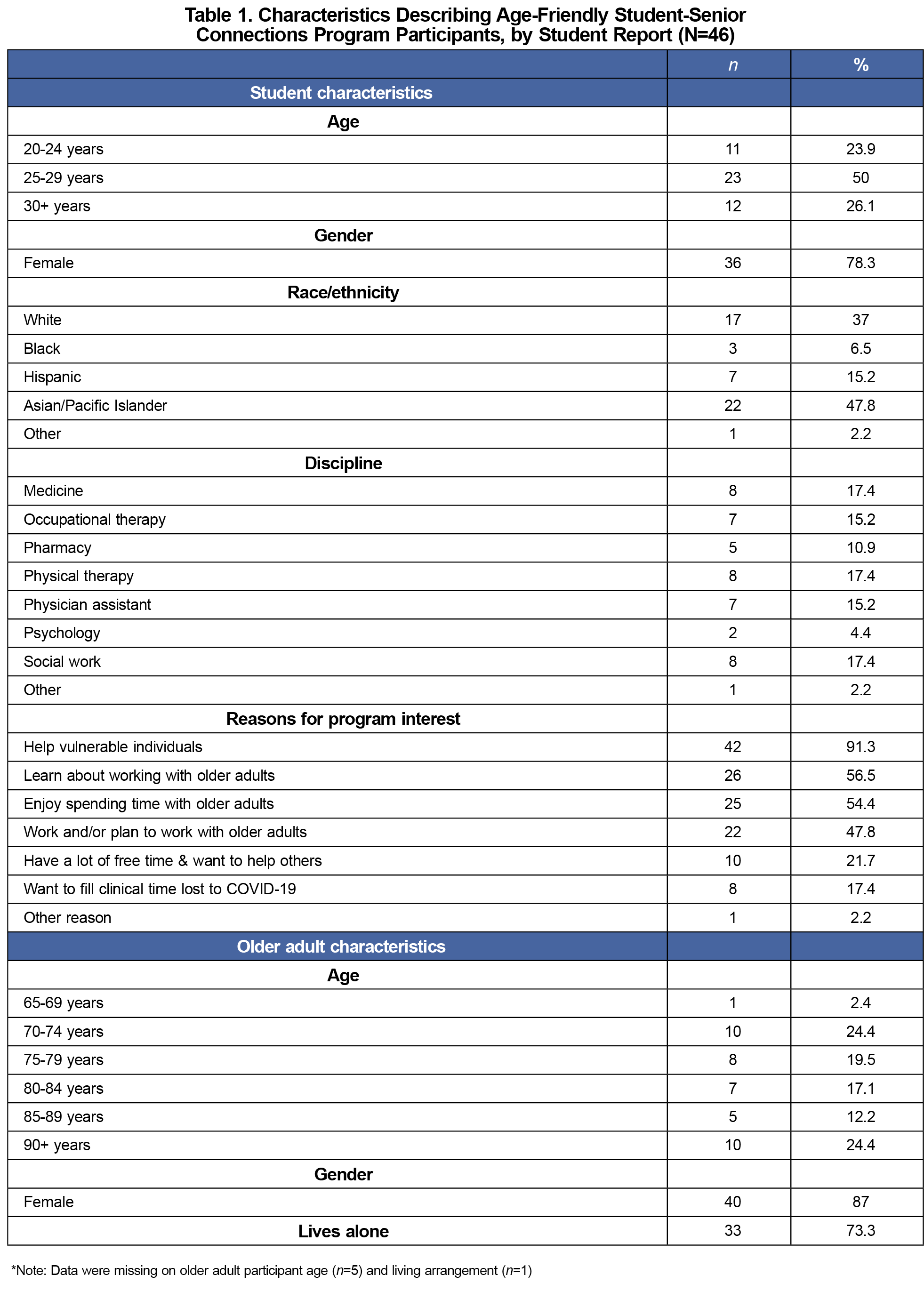

Data were available from 46 IP students, representing a subset (38.6%) of program participants. We found no statistically significant differences between respondents and nonrespondents across age, gender, race, and discipline of study.

Participants (Table 1) were mostly women (78.3%) between the ages of 20-29 years (73.9%) and mostly Asian/Pacific Islander (47.8%) and White (37.0%), reflecting the gender and ethnicity of our graduate health professional student population. Overwhelmingly, 91.3% of students volunteered to participate in the program to “help vulnerable individuals.” Participants also learned to work with (54.4%) or enjoyed spending time with older adults (54.4%). Several students spent free time in AFSSC to help others (21.7%) and fill clinical time lost to social distancing restrictions (17.4%). Their older adult partners were mostly female (87%), living alone (73.3%), and between the ages of 70-84 years (61.0%).

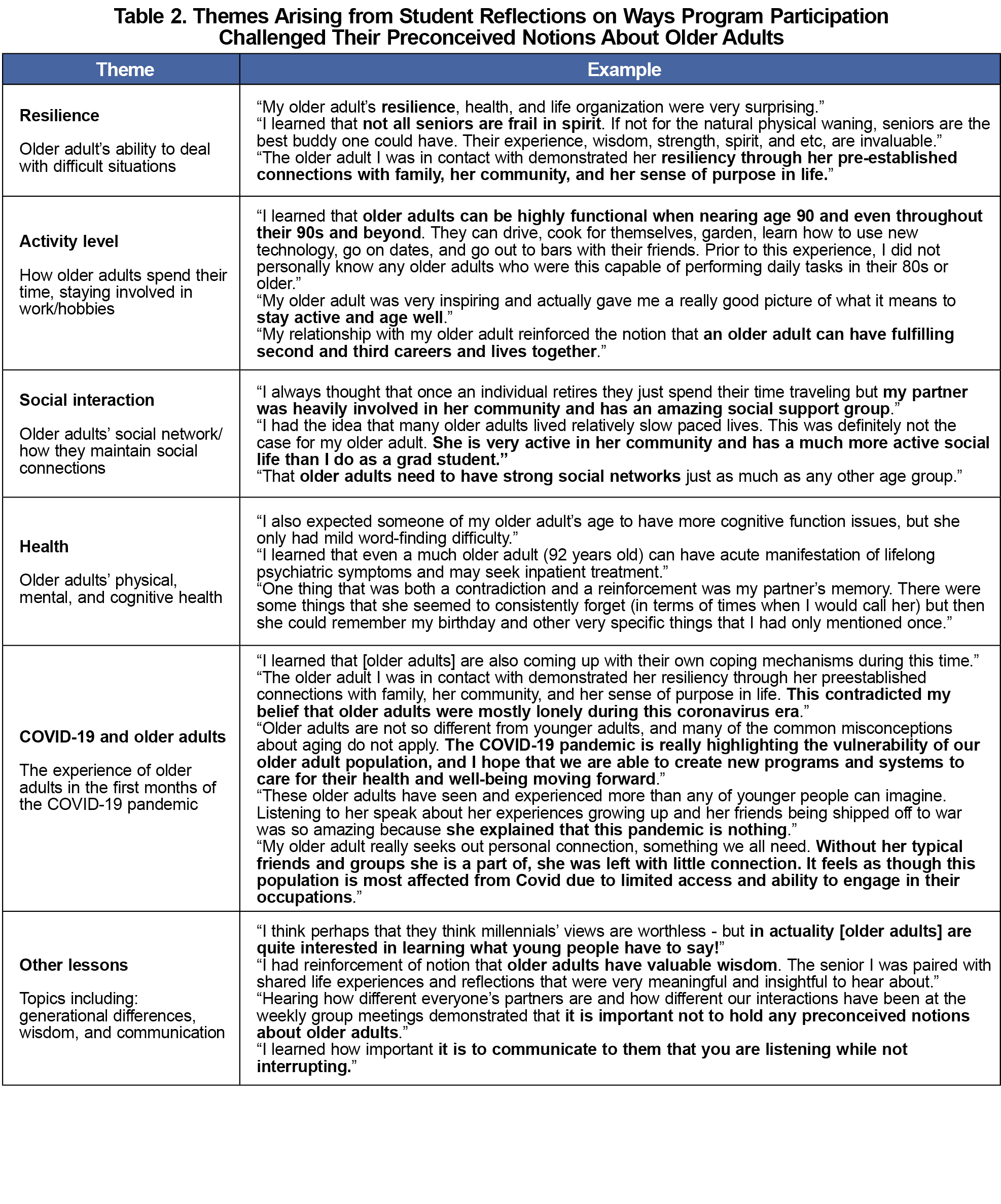

Through their experiences, students reported (Table 2) recognition of older adults’ resilience, activity level, social interactions, and health, noting how observed symptoms varied from their preconceived notions. Students also discussed their partners’ experiences during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting both their resilience and hardships.

Results suggest IP graduate health professions students’ older adult perceptions may become more positive with participation in intergenerational, phone-based service-learning programs. Student response themes suggest that negative older adult perceptions persist in society but may improve through meaningful elderly interactions. Providing students with geriatric educational training may improve patient care quality.

Students volunteering to help vulnerable individuals (91.3%), may have entered the program with negative elderly stereotypes/perceptions consistent with benevolent ageism,22 a paternalistic view that older adults are frail, less competent, and require special accommodations/protection. Challenging these beliefs enables IP students to recognize the diversity in aging and support healthy older adults’ aging and independence in future clinical practice.

Study limitations included possibly underidentifying changes in student perceptions. Because students were asked to remember and report on potentially negative perceptions of older adults prior to program involvement, responses were subject to recall bias and social desirability issues. This may have made them less likely to admit to having ageist beliefs, resulting in underreporting of positive change, overreporting of neutral responses, and lowering response rates. Pandemic issues also limited study follow-up with some students.

This study found that IP health graduate students and older adults engagement challenged students’ negative preconceived notions about aging and the geriatric population. Introduction of weekly, student-older adult telephone/audio interactions was a novel teaching approach necessitated by the pandemic and holds promise for continued geriatric education use. Future studies should consider whether student preconceived notions of older adults is informed by their ethnic/racial and gender backgrounds. Work is needed to more broadly implement the IP geriatric program, assess program efficacy, the magnitude of intervention necessary to challenge stereotypes, and to foster positive attitudes toward aging older adults.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine 2021 Annual Spring Conference, May 2021 (virtual), and the USC Family Medicine Research Day, February 1, 2023 (Los Angeles).

Disclaimer: Dr Yonashiro-Cho’s work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health under award number KL2TR001854 (for salary, fringe, research supplies, and administrative/co-curricular activities) and UL1TR001855 (for administrative/co-curricular activities). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- van Zuilen MH, Granville LJ. Playing the long game: addressing the shortage of geriatrics educators. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):647-649. doi:10.1111/jgs.15901

- Meiboom AA, de Vries H, Hertogh CMPM, Scheele F. Why medical students do not choose a career in geriatrics: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):101. doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0384-4

- Palsgaard P, Maino Vieytes CA, Peterson N, et al. Healthcare professionals’ views and perspectives towards aging. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15870. doi:10.3390/ijerph192315870

- Reilly JM, Stevens G, Halle A,et al. Interprofessional, older adult, team-based home visits: a 6-year prospective analysis. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2020;(May). doi:10.1080/02701960.2020.1758081

- Reilly JM, Halle A, Resnik C, et al. Qualitative analysis of an inter-professional, in-home, community geriatric educational training program. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2021;7(Feb):2333721421997203. doi:10.1177/2333721421997203

- Mendoza De La Garza M, Tieu C, Schroeder D, Lowe K, Tung E. Evaluation of the impact of a senior mentor program on medical students’ geriatric knowledge and attitudes toward older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39(3):316-325. doi:10.1080/02701960.2018.1484736

- Gonzales E, Morrow-Howell N, Gilbert P. Changing medical students’ attitudes toward older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2010;31(3):220-234. doi:10.1080/02701960.2010.503128

- Milutinović D, Simin D, Kacavendić J, Turkulov V. Knowledge and attitudes of health care science students toward older people. Med Pregl. 2015;68(11-12):382-386. doi:10.2298/MPNS1512382M

- Basran JFS, Dal Bello-Haas V, Walker D, et al. The longitudinal elderly person shadowing program: outcomes from an interprofessional senior partner mentoring program. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2012;33(3):302-323. doi:10.1080/02701960.2012.679369

- Ross L, Jennings P, Williams B. Improving health care student attitudes toward older adults through educational interventions: A systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39(2):193-213. doi:10.1080/02701960.2016.1267641

- Moonen G, Perrier L, Meiyappan S, Akhtar S, Crampton N. COVID-19 pandemic partnership between medical students and isolated elders improves student understanding of older adults' lived experience. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):636. Published 2022 Aug 2. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03312-z.

- Fukuma N, Reilly JM. Geriatrics education: phone calls with older adults and medical students. Fam Med. 2023;55(7):471-475. Doi:10.22454/FamMed.149721 .

- Burnett J, Broussard J, Savitz S, et al. Health professional student-led social phone calls to address loneliness in aging -in-place adults after stroke. Innovations in Aging. December 2023. 7(Supplement_1):1052-1057. doi:10.1093/geroni/igad104.3380.

- Nathanson M, Rau S, Jiang E, Phyllis S. Friendly calls to seniors: an interprofessional student volunteer program. Am J of Ger Psych. 2021. 29 (4): S130-S132. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2021.01.126

- Office EE, Rodenstein MS, Merchant TS, Pendergrast TR, Lindquist LA. Reducing social isolation of seniors during COVID-19 through medical student telephone contact. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(7):948-950. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.003

- United Nations. COVID-19 and Older Persons: A Defining Moment for an Informed, Inclusive and Targeted Response. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/news/2020/05/covid19/.

- Joosten-Hagye D, Katz A, Sivers-Teixeira T, Yonshiro-Cho J. Age-friendly student senior connection: students’ experience in an interprofessional pilot program to combat loneliness and isolation among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(5):668-671. doi:10.1080/13561820.2020.1822308

- Karel MJ, Knight BG, Duffy M, Hinrichsen GA, Zeiss AM. Attitude, knowledge, and skill competencies for practice in professional geropsychology: implications for training and building a geropsychology workforce. Train Educ Prof Psychol. 2010;4(2):75-84. doi:10.1037/a0018372

- Koren ME, Hertz J, Munroe D, et al. Assessing students’ learning needs and attitudes: considerations for gerontology curriculum planning. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2008;28(4):39-56. doi:10.1080/02701960801963029

- Rogers AT, Gualco KJ, Hinckle C, Baber RL. Cultivating interest and competency in gerontological social work: opportunities for undergraduate education. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2013;56(4):335-355. doi:10.1080/01634372.2013.775989

- Cowen AS, Keltner D. Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(38):E7900-E7909. doi:10.1073/pnas.1702247114

- Cary LA, Chasteen AL, Remedios J. The Ambivalent Ageism Scale: developing and validating a scale to measure benevolent and hostile ageism. Gerontologist. 2017;57(2):e27-e36. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw118

There are no comments for this article.