Developing a national medical education curriculum presents challenges including institutional differences, multiple stakeholders, competing priorities, and varying perspectives on educational best practices. Factors that contribute to successful curriculum design and implementation include a systematic approach, careful planning, intentional collaboration, and active inquiry. Modeled after Kern’s 6-Step Approach for Curriculum Development for Medical Education, we authors provide a practical and iterative framework for other medical education leaders to utilize when creating and disseminating large-scale curricula across institutions. We share insight and tips from the experience of developing a national family medicine subinternship curriculum that was based on specialty values and competency-based assessment. We provdie an example of how this framework can be best utilized for development of durable and relevant curriculum that will provide a reliable standardized clinical experience that is also flexible enough to allow individual institutions to customize the rotation to their unique characteristics.

Subinternships are widely recognized by both faculty and residents to be one of the most critical experiences for preparing students to transition into residency.1-2 In 2011, the Alliance of Clinical Education recommended that each specialty develop a standardized subinternship curriculum.3 Internal medicine and pediatrics responded in turn,4-5 but family medicine had not yet developed a comparable standardized curriculum by 2019.

Standardized clinical rotation curricula serve many purposes; they fulfill medical school and residency program requirements, establish shared goals and objectives across training sites, and provide structure and quality of shared learning experiences.6 Recognizing these advantages, we identified a clear need for a standardized curriculum tailored to family medicine’s unique breadth of scope. We initiated a 3-year process to develop a durable, nationally-relevant, specialty-specific subinternship curriculum that could meet the needs of diverse stakeholders across institutions.

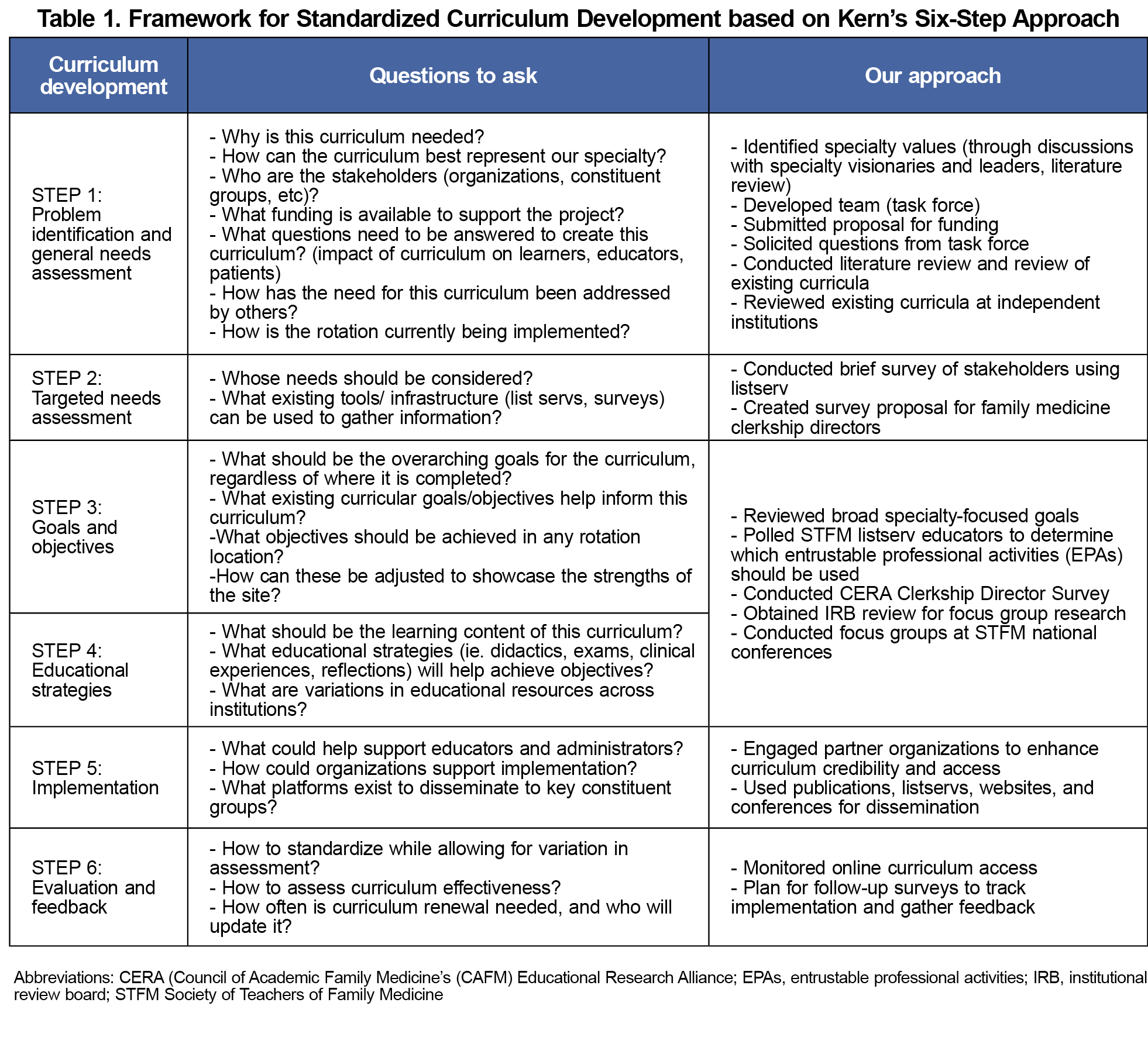

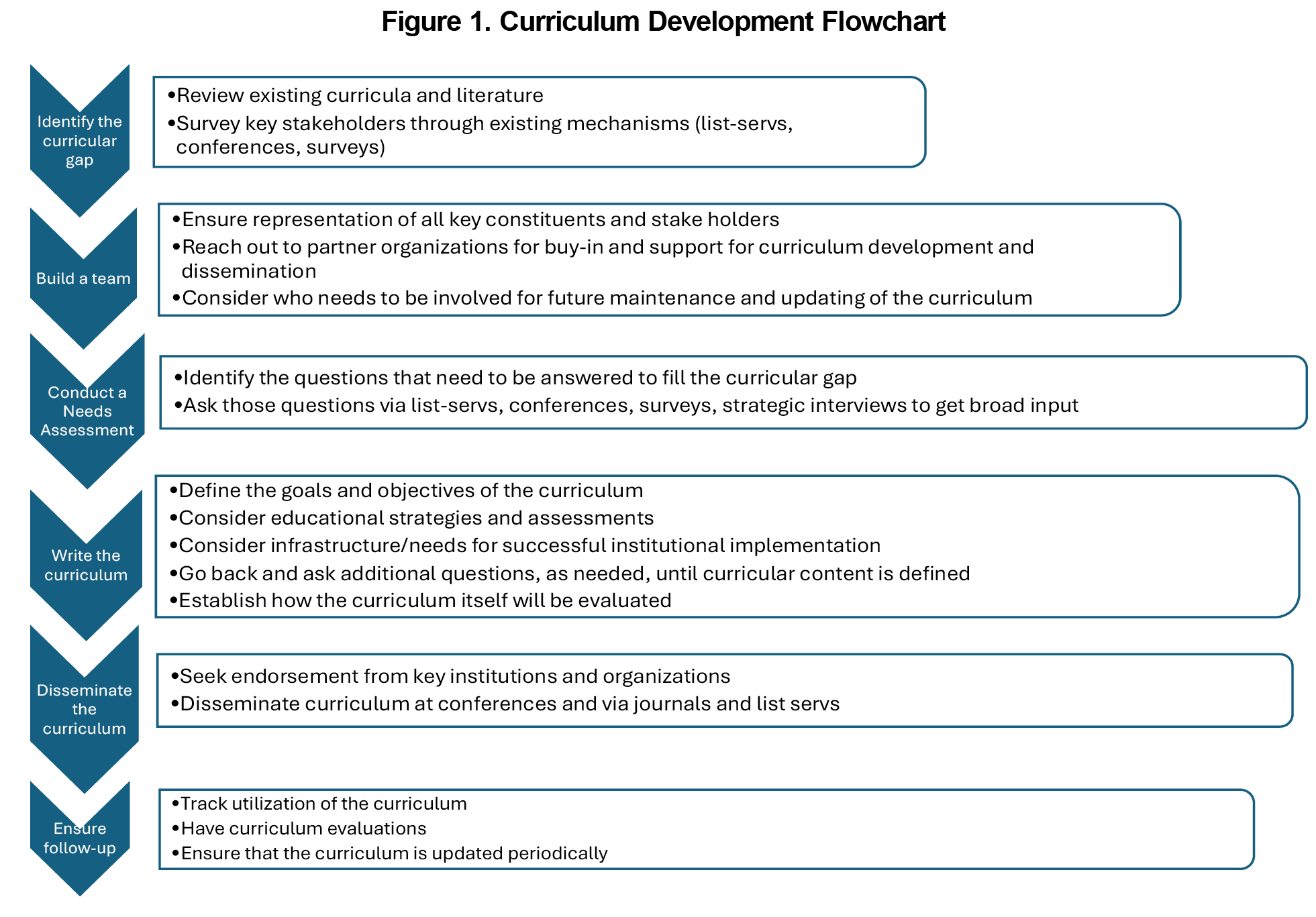

Developing such a curriculum presented challenges, including significant variability in existing family medicine subinternship structures and the need to carefully consider both the needs of learners and institutional priorities. Using Kern’s Six-Step Approach to Curriculum Development,7 we designed an adaptable model for medical educators to create curricula for broad implementation across institutions (Table 1). Here, we illustrate the framework’s application, with examples from our family medicine subinternship curriculum. Our guided model integrates components of each step in the order we recommend (Figure 1). However, the process is often iterative rather than strictly linear, so we encourage readers to review the full six-step model in advance.

Step 1: Problem Identification and General Needs Assessment

Start by identifying the problem and asking big questions, such as the curriculum’s purpose, overarching goals, relevant stakeholders, and intended outcomes. Analyzing both the current and ideal approaches to the problem will inform the curricular gap. Early consideration of available resources (eg, funding, staff support, partnerships) can facilitate a more efficient development process and increase the likelihood of successful implementation.

We decided family medicine values would be the foundation of the subinternship curriculum. We assembled a task force with key constituents representing a diversity of perspectives. We reviewed relevant curricula from internal medicine and pediatrics subinternships, and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Family Medicine National Clerkship (NCC).8 A review of 10 randomly-selected family medicine subinternships revealed wide variation in structure and content. To address this, we planned a step-wise process to identify core curricular elements to develop national standards. Our partnership with STFM provided access to its national network, committees, funding, and staff support.

STEP 2: Targeted Needs Assessment

Assess whose needs should be considered for the targeted needs assessment, and plan for how that can be obtained. Identify high-priority, specific questions and review existing resources for data gathering in advance to avoid a potentially overwhelming process.

Initially, we gathered information from family medicine undergraduate medicine educators through the STFM collaborative list serv. Next, we surveyed clerkship directors through the Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA)9 to evaluate curriculum outcomes and gathered preferred evaluation methods.

STEP 3: Goals and Objectives

Articulate the overarching goals of the curriculum, which should be guided by primarily by findings from step 1, and objectives from step 2. Receive feedback from stakeholders and focus on what is practical and realistic to implement, as too much specificity can decrease utilization. We learned that focus groups generated valuable content from more nebulous questions, but list-serv polls and surveys were more helpful when questions were well-defined.

A mixed-methods approach helped us answer remaining critical questions. We polled an STFM list serv to determine which entrustable professional activities (EPAs) should be considered for the subinternship. Focus groups at STFM national conferences helped extract specific needs regarding curricular content, structure, setting, and assessment.

STEP 4: Educational Strategies

Consider essential content to include in your curriculum and the educational strategies (ie, readings, didactics, exams, clinical experiences, reflection pieces, etc) that will help achieve your objectives. Consider the variations in educational settings and resources across institutions.

Through our focus groups, we learned that direct patient care with supervision was the preferred method of learning and assessment by educators and learners on a subinternship rotation. Based on continuity-of-care principles, participants recommended that students experience at least two different patient care settings (eg, inpatient, outpatient, labor and delivery, home, telehealth, etc). To support the undergraduate to graduate medical education continuum, EPAs were mapped to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones as a framework for evaluation. The STFM National Clerkship Curriculum became our recommended prerequisite rotation.

Consider existing platforms to ensure that the curriculum is disseminated to key constituent groups. Request endorsement from strategic organizations that can support the distribution of the curriculum. Providing faculty and staff support recommendations as part of the curriculum can facilitate successful curriculum implementation at each site.

We used a modified Kemp model to showcase our curriculum for its flexibility in design, highlighting the interdependence of the core components, 11 and presented the curriculum at national conferences. Engaged partner organizations were key to enhancing validity and access to the curriculum. The curriculum was approved by the STFM Board of Directors, American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD). The curriculum became available to download via the STFM website.12 An announcement was published in the Annals of Family Medicine13 and the curriculum was disseminated through STFM Messenger and STFM member list servs. We learned the importance of ongoing dissemination of the curriculum, as we observed spikes in downloads after conference presentations.

STEP 6: Evaluation and Feedback

Plan for how to gather feedback for curricular refinement, considering how frequently the curriculum should be reviewed, and who will be responsible for updates. Most experts recommend conducting formal medical school curriculum reviews every 3-5 years to ensure alignment with evolving health care needs, educational practices, and accreditation standards.14-15 Establish these plans prior to curriculum rollout, as they are challenging to integrate retrospectively. Consideration of the curricular context may guide timely updates to stay relevant and useful, accounting for changes in GME milestones, the shift toward competency-based education, and the evolving landscape of family medicine and healthcare delivery.

We designed two editable evaluation forms: one for students and one for the subinternship site.16-17 This allowed a standardized approach to subinternship learner evaluations while accommodating individual programs' differences. The STFM Medical Student Education Collaborative steering committee would be responsible for periodically reviewing and updating the curriculum.

Successful development of a national curriculum requires navigating challenges of varying stakeholder needs and opinions through careful planning, collaboration, and evidence-based inquiry. Through our multimodal engagement with numerous stakeholders and curricular constituents, we learned that zooming in and out, having flexibility between big-picture planning, and considering each step were key to our success. No curriculum fits every institution, and balancing specificity with adaptability is essential to creating a useful curriculum.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The Curriculum Task Force received $10,000 from the STFM Special Project Fund.

Previous Presentations on Related Content:

- Sairenji T, Stumbar S, de la Cruz M, et al. What Do You Envision From a Family Medicine Subinternship? Seeking Input to Create a National Curriculum. Symposium at STFM Conference on Medical Student Education. Portland, OR. February 2020.

- Stumbar S, Babalola D, Kelley D, de la Cruz M, Olsen M, Sairenji T. Creating a National Family Medicine Sub-internship Curriculum: Seeking Input from Specialty Stakeholders! Breakfast session at STFM Conference on Medical Student Education. Portland, OR. February 2020.

- Sairenji T, Stumbar S, Stubbs C, et al. National Sub-internship Curriculum- Updates and Final Input. Live lecture-discussion at STFM Conference on Medical Student Education. 2021. Virtual.

- Stumbar S, de la Cruz M, Adams C, Babalola D, Kelley D, Sairenji T. STFM National Sub-internship Curriculum: Presentation and Implementation. January 2022. Virtual.

- Sairenji T, Stumbar S, Onyekaba C, Stumbar S. Family Medicine National Sub-internship Curriculum: Feedback and Implementation. Panel Discussion at STFM Annual Spring Conference, Tampa, FL. May 2023.

- Sairenji T, Stumbar S, Chessman A. STFM Research Paper of the Year: Using Research to Inform the Development of the Family Medicine Sub-internship Curriculum. Completed research presentation at STFM Annual Spring Conference. Tampa FL. May 2023.

Conflict Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Lyss-Lerman P, Teherani A, Aagaard E, Loeser H, Cooke M, Harper GM. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):823-829. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a82426

- Pereira AG, Harrell HE, Weissman A, Smith CD, Dupras D, Kane GC. Important skills for internship and the fourth-year medical school courses to acquire them: a national survey of internal medicine residents. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):821-826. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001134

- Reddy ST, Chao J, Carter JL, et al. Alliance for clinical education perspective paper: recommendations for redesigning the “final year” of medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(4):420-427. doi:10.1080/10401334.2014.945027

- Vu TR, Angus SV, Aronowitz PB, et al; for the CACTI Group. (CDIM-APDIM Committee on Transitions to Internship). The Internal Medicine Subinternship – More Important Now Than Ever: A Joint CDIM-APDIM Position Paper. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1369-1375. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3261-2

- Council on Medical Student Education in Pediatrics; Association of Pediatric Program Directors. Pediatric sub internship curriculum. 2009. Available at: https://media.comsep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/30172802/COMSEP-APPDF.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2024.

- Elnicki DM, Gallagher S, Willett L, et al; Clerkship Directors in Internal MedicineAssociation of Program Directors in Internal Medicine Committee on Transition to Internship. Course offerings in the fourth year of medical school: how U.S. medical schools are preparing students for internship. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1324-1330. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000796

- Kern DE. Patricia A Thomas, and Mark T Hughes. Curriculum Development for Medical Education : A Six-Step Approach. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. STFM National Clerkship Curriculum. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine; 2023. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://www.stfm.org/media/1828/ncc_2018edition.pdf

- Sairenji T, Stumbar SE, Garba NA, et al. Moving Toward a Standardized National Family Medicine Subinternship Curriculum: Results From a CERA Clerkship Directors Survey. Fam Med. 2020;52(7):523-527. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.209444

- Morrison GR, Ross SM, Kemp JE, Kalman H. Designing effective instruction.6th ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Sub-internship curriculum. 2022. Available at: https://www.stfm.org/teachingresources/curriculum/subicurriculum/. Accessed Nov 25, 2024.

- Walters E, Sairenji T. STFM Task Force releases a standardized family medicine sub-internship curriculum. Ann Fam Med. 2022;20(3):289-290. doi:10.1370/afm.2839

- Gruppen LD, Mangrulkar RS, Kolb SJ. The promise and practice of competency-based medical education. Med Educ.2017;51(1):11-19. doi:10.1111/medu.13183

- Harden RM. Developing and implementing a competency-based curriculum for the health professions: the time for change. Med Teach. 2001;23(5):466-472. doi:10.1080/01421590120075521

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2014. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/cbme/core-epas. Accessed May 20, 2025.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Family Medicine Milestones. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2019. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/FamilyMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2025.

There are no comments for this article.