Introduction: Poster displays are commonly used to present scholarly activity. Most current research evaluates posters’ visual appeal. Isolated studies looking at knowledge transfer have evaluated standalone posters. The innovation of BetterPoster highlighted the idea that design may be as important as poster content for knowledge transfer. The objective of this study was to evaluate the difference in knowledge transfer between poster designs.

Methods: We randomized participants to two different poster designs (48 viewed a traditional poster design; 46 viewed the BetterPoster model). We obtained baseline knowledge via anonymous 5-question pretest. Participants viewed their assigned poster then completed a 10-question posttest. Eight questions tested general medicine knowledge about the topic and two questions tested the case’s scholarly question and conclusion. We used a full factorial model analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to analyze test scores between the two posters for the 10-question posttest and the 2-question subset.

Results: A total of 94 participants recruited at a family medicine conference completed the study. We conducted a full factorial model ANCOVA of the 10-item posttest summed score, which was not found to be significant. A similar analysis on the two posttest learning point items showed that participants viewing the BetterPoster scored significantly higher, (F [1, 91]=8.00, P=.006).

Conclusion: Our study was designed to move past evaluating visual appeal of poster design to effectiveness of knowledge transfer. We found that poster design did not impact knowledge transfer of the general case topic; however, it did improve knowledge related to key concepts of the case.

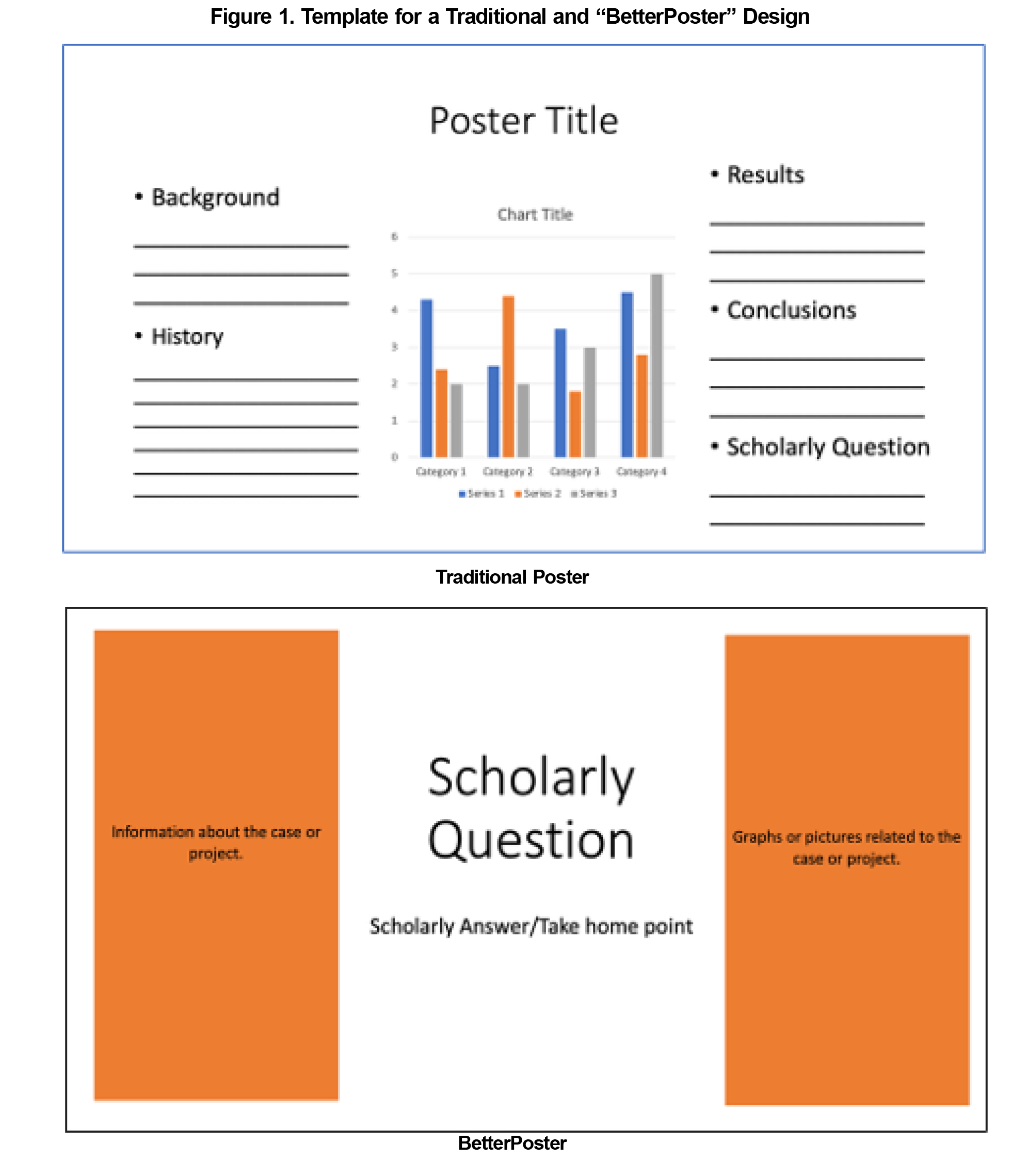

The academic poster is a popular format for disseminating clinical knowledge. The traditional poster design is predominantly used to present information (Figure 1). The traditional poster design is characterized by ample charts and graphs while mirroring the configuration of a written publication.1-3 However, this design often leads to dense text blocks, a cluttered appearance, and even omission of important information to increase aesthetic appeal.1-3

Recently, new layouts have emerged to further optimize and display information. One popular iteration is the BetterPoster (“Poster 2.0”) design (Figure 1).4 Compared to traditional academic posters, BetterPoster is graphically redesigned to display research conclusions prominently in a large and easy-to-read font. This central focus is then flanked by abbreviated introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections, along with relevant figures and graphs. Preliminary data from the BetterPoster design team shows it is a preferred layout for engagement compared to the traditional design by both conference presenters and attendees at three different conferences5 Evidence also suggests that BetterPoster displays attracted more visitors compared to traditional posters.5

To date, research regarding the acquisition of clinical knowledge between poster formats is limited. A 2009 pilot study found that 39% of respondents believe posters are a good medium for transferring knowledge and are a valid form of academic publication.6 A 2013 review of 15 studies evaluated standalone posters and concluded knowledge transfer occurs best in the setting of additional educational materials; however, none of the studies evaluated change in knowledge, behaviors, or attitudes.7 A 2016 study examining knowledge retention from family medicine poster presentations demonstrated retention rates of general knowledge at 14.9% (30 days) and 11.3% (90 days).8 No studies to date have directly compared academic research poster designs regarding transfer of knowledge. Our aim was to fill this gap and evaluate the role of poster design in immediate knowledge transfer. Given the preliminary evidence from the BetterPoster design team,5 we anticipated that knowledge transfer would be higher with BetterPoster.

We used a randomized, single-blinded, controlled trial study format. The study was determined to be exempt from review by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board. We recruited participants at the Uniformed Service Academy of Family Physicians (USAFP) 2023 Annual Meeting. A previously presented poster from the USAFP 2022 meeting was used for the traditional design (see Supplement 1) and a second poster using the same content was made, applying BetterPoster design (Supplement 2). Participants were excluded if they self-reported familiarity with the case or did not have a medical degree. An online randomization tool was utilized.9 Participants were given a sealed envelope with their randomization number, assigning them to view either the traditional or BetterPoster design.

Participants provided basic demographic data and completed an anonymous pretest consisting of five general knowledge questions about the topic (Supplement 3). After the pretest, participants were directed to a viewing area according to their assignment. Participants were instructed to engage as they would any poster display hall; no data were collected regarding time spent viewing the poster. There were no presenters for the posters. Following the viewing, participants were directed away from sight of the poster to complete the posttest.

The posttest contained 10 questions, eight asking general information about the case and two questions specific to the scholarly question and conclusion (considered key take-away points of the case). Of these two questions, one included a three-part answer (graded by one of the authors), and the second question was true/false, resulting in four total answers for grading in these two questions. Two of the authors, both experienced medical educators, developed the pre/posttest questions. To ensure the were no significant differences between the two groups, we conducted the following statistical analyses on the demographics: χ2 test (gender), Fisher exact test (level of medical training), and independent samples t tests (age). We used a two-sample t test to compare pretest scores. Since significance for this test was P=.05, we used a full factorial analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for pretest score for the posttest analysis. Evidence of knowledge transfer, the primary outcome, was measured by the number of correct questions on the 10-item posttest. We then conducted exploratory analysis on the two questions focused on the scholarly question and conclusion to see if the BetterPoster design impacted acquisition of key concepts.

Although we could not approach all the estimated 500 conference attendees, 97 did opt to participate. However, three did not complete the posttest (Figure 2). Of the remaining 94 participants, 48 were randomized to the traditional poster design and 46 to the BetterPoster. Demographic analysis of self-reported age, gender, and level of training showed no significant differences between the groups (Table 1).

As the primary outcome, the average correct score for the traditional poster was 6.83 (SD ±1.96) compared to 7.33 (±SD 1.35) for the BetterPoster design. Analysis of the full 10-item posttest score found the results were not statistically significant. Given these results, we added an exploratory analysis on the two-question posttest score. In this follow-up analysis, the average number of correct questions for the traditional poster was 1.45 (SD±0.57) compared to 1.75 (SD ±0.35) for the BetterPoster. For this two-question posttest, the BetterPoster scored statistically significantly higher (F [1, 91]= 8.00, P=.006, P<.01; Table 2).

Contrary to our hypothesis, our study’s results indicate no difference in overall knowledge transfer between poster designs. However, the exploratory analysis suggests that viewers of BetterPoster design were more likely to walk away understanding key concepts (ie, scholarly question and conclusion) of the poster compared to viewers of the traditional design. Furthermore, the National Training Laboratories learning pyramid reports 10% of information is retained through a passive visual learning experience such as our poster designs.10 As a learning tool the poster is categorized as a passive virtual learning experience, and thus as educators we maintain that the 15% difference in average post-test scores for the 2-question test represents an educationally significant difference for the attendee.

This study is limited by a small sample size at a single conference and specialty, thus our findings should be interpreted with caution. Although efforts were made to conceal the posters until after participants were assigned, we acknowledge the possibility that some participants may have unintentionally seen the posters prior to the study. There should be consideration for alternate poster designs outside of these two structures. Finally, a study to assesses long-term retention would help support a specific poster design.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to move beyond poster engagement to evaluate the role of academic poster design in immediate knowledge transfer. This is important because of the ubiquitous and nearly unquestioned application of traditional poster designs for the dissemination of academic medical information. Thus, the goal of our study was to evaluate the role of poster design in the immediate transfer of knowledge. While we acknowledge that engagement is important, conference attendees’ desire may be to walk away from a poster with a “pearl” of information. Although the ideal format for this experience has not yet been determined, our study represents an important first step in addressing this question.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christy Ledford, PhD, for her assistance with data analysis, Anna Pendrey, MD, for her assistance with study design, and Dr Anne Myers for her assistance with editing.

Presentations: This study was presented as follows:

- Is Better Smarter? – An RCT of knowledge transfer based on poster design. Podium presentation for Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians. New Orleans, LA. March 2024.

- imPOSTER: Does Poster Design Impact Knowledge Transfer? A Randomized Look at New vs Traditional Poster Design. Completed Research Project presentation at Society of Teachers of Family Medicine 2024 Annual Spring Conference. Los Angeles, CA. May 2024.

Conflict Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, US Department of Defense, US Air Force, or US government.

References

- Gemayel R. How to design an outstanding poster. FEBS J. 2018;285(7):1180-1184. doi:10.1111/febs.14420

- Calbraith D. How to develop and present a conference poster. Nurs Stand. 2020;35(9):46-50. doi:10.7748/ns.2020.e11468

- Shelledy DC. How to make an effective poster. Respir Care. 2004;49(10):1213-1216.

- How to create a better research poster in less time (#betterposter Generation 1). YouTube [video]. July 13, 2020. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RwJbhkCA58&t=1171s

- Flemming P. What is the optimal design for a scientific poster? insights from the founder of the #betterposter movement. The Publication Plan. August 25, 2020. Accessed July 1, 2023. https://thepublicationplan.com/2020/08/25/what-is-the-optimal-design-for-a-scientific-poster-insights-from-the-founder-of-the-betterposter-movement/

- Rowe N, Ilic D. What impact do posters have on academic knowledge transfer? A pilot survey on author attitudes and experiences. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9(1):71. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-9-71

- Ilic D, Rowe N. What is the evidence that poster presentations are effective in promoting knowledge transfer? A state of the art review. Health Info Libr J. 2013;30(1):4-12. doi:10.1111/hir.12015

- Saperstein AK, Lennon RP, Olsen C, Womble L, Saguil A. Information retention among attendees at a traditional poster presentation session. Acta Med Acad. 2016;45(2):180-181. doi:10.5644/ama2006-124.178

- Randomly assign subjects to treatment groups. GraphPad. https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1.cfm

- Outside S. Pushing your teaching down the learning pyramid. Science Outside. Published May 19, 2020. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.scienceoutside.org/post/pushing-your-teaching-down-the-learning-pyramid

There are no comments for this article.