Introduction: Over the last three match cycles (2023, 2024, and 2025), a coordinated effort has led family medicine residency applicants to apply to fewer programs, resulting, on average, in 21% fewer US applications for programs to review. Whether this decline is a cause for celebration or concern is unclear. How has the reduction affected the number of applicants programs considered desirable?

Methods: For the past 3 years, the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Family Medicine Residency Program (FMRP) has consistently used a two-faculty review process to decide which applicants are invited to interview. We conducted a χ2 test of independence to assess the relationship between the application year and the percentage of applicants invited to interview in the first round.

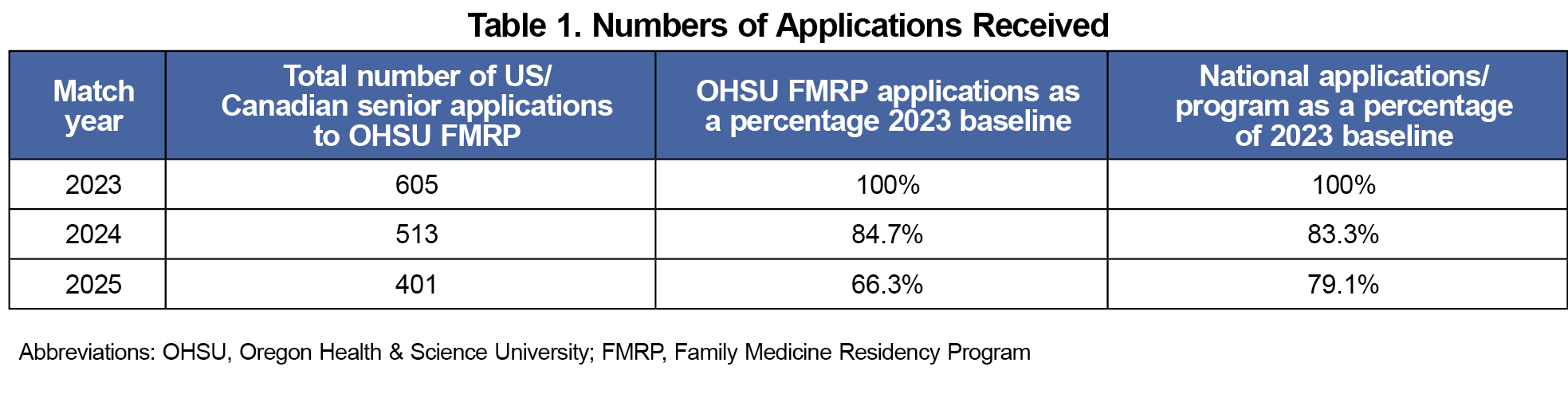

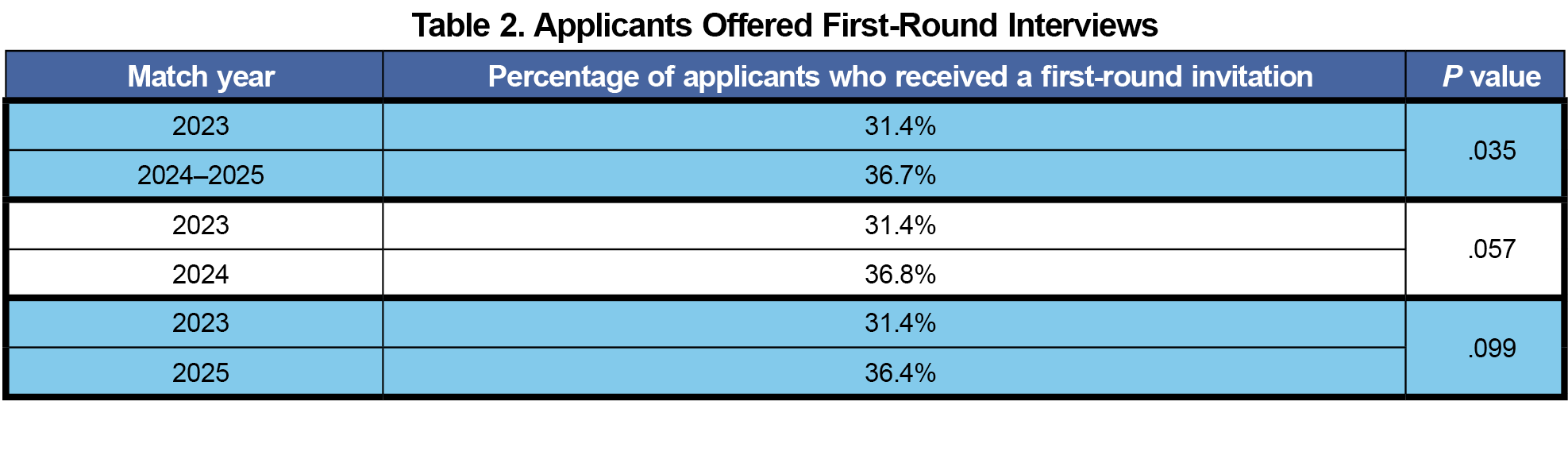

Results: Using 2023 as a baseline, the OHSU FMRP received 15.2% and 33.7% fewer applicants in the 2024 and 2025 match cycles, respectively. Concurrently, 33.7% of applicants in 2024 and 36.4% of applicants in the 2025 match were offered an interview in the first wave of interviews, which is higher than in 2023.

Conclusions: These data indicate that although the number of applicants decreased over the last three match cycles, applicant quality has remained consistent. A broader analysis is needed to understand the impact on programs and the factors influencing applicants’ choice of programs in the era of virtual interviews and program signaling.

The number of applications per applicant for graduate medical education positions in the United States has steadily increased over the last 2 decades.1 This “application fever”2 challenges programs and applicants. Application volume can hinder holistic review3 and encourage filtering by convenience metrics such as medical licensing exam (USMLE/COMLEX) scores that do not clearly predict resident performance.4 By the 2020 match season, family medicine programs received, on average, 293 US senior applications (MD and DO) per program.1

Recently, coordinated efforts have been made to smooth the undergraduate medical education to graduate medical education transition.5,6 These include increased data transparency for applicants7 and the introduction of program preference signals,8 allowing applicants to express interest in a limited number of programs at the time of their application.

Over the last three match cycles (2023–2025), the number of US senior applicants for family medicine has been stable, at 4,270 to 4,163. Meanwhile, the number of applications per applicant declined 13%, resulting in 21% fewer applications per program. In 2025, the average family medicine program received 205 US senior applications.1

For programs, the difference between reviewing 293 files and 205 files per cycle is significant. However, whether this drop is a cause for celebration or concern for program directors is still unclear. As applicants utilize decision-making tools, transparent program data, and preference signals, are they applying to programs with a better fit, or are they simply applying to fewer programs?

For the past three match cycles (2023–2025), we have utilized a stable systematic review of applications. Two faculty members review each file, and a structured process is used to determine who is offered an interview in round one. First-round offers have no quota or cap. Because the process has not changed, the percentage of applicants offered interviews in round one can provide insight into application strength.

This is a single institution descriptive study that evaluates the outcomes of our interview offer rubric and the decline in application volume observed over the last three application cycles. We hypothesized that, despite fewer applications, the proportion of first-round interview offers has remained stable, suggesting that applicant quality has remained stable as application quantity has declined.

Application data from North American MD and DO applicants to the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Family Medicine Residency Program (FMRP) were compiled from the 2023 to 2025 match cycles. All faculty participating in file reviews completed a standardized file norming session (in person or virtual). Interview decision criteria remained consistent across all years. These include review of letters of recommendation, personal statement, medical school recognition/accomplishments, school performance, and board performance. File readers assign a score to letters of recommendation and personal statements. Additionally, they are encouraged to consider the entirety of the application and account for distance traveled and barriers overcome. We analyzed applicant volume and the percentage invited for a first-round interview. We conducted a χ2 test of independence to assess the relationship between application year and first-round interview rates. In addition to comparing 2024 and 2025 independently against 2023, we also compared pooled data from 2024–2025 against 2023 because (a) total number of applications decreased in both 2024 and 2025, and (b) signaling was first introduced in 2024. This project was determined to be exempt from review by the OHSU Institutional Review Board.

Using the 2023 match season as our baseline, we received 15.2% fewer applications from US/Canadian applicants in 2024 and 33.7% fewer in 2025 (Table 1). Concurrently, the percentage of applicants offered first-round interviews ranged from 31.4% in 2023 to 36.4% in 2025 (Table 2).

A χ2 test of independence demonstrated an association between application cycle and the percentage of applicants who received a first-round interview offer when combining results from the 2024–2025 application cycles (P=.035).

Applications to the OHSU FMRP declined in both the 2024 and 2025 match cycles. However, the proportion of first-round interview offers remained stable, and our invitation benchmarks did not change. This finding suggests that applicant quality was consistent or proportionally stronger despite the lower volume.

Several factors may explain the decline. At a national level, we may be seeing early signs of “disruptive innovation” in residency recruitment.9 The shift to virtual interviews during COVID-19 likely inflated applications per applicant;10 current declines may reflect a return to baseline. Additionally, the use of program signals may be influencing applicant preferences and behavior.11 The reduced application volume has lessened faculty and administrative burden while maintaining applicant fit. This shift has freed up time for faculty to focus on high-impact work, including holistic review, curriculum redesign, and resident mentorship, advising, and coaching.

Future areas of interest include examining whether other programs are experiencing similar trends and identifying the key drivers behind applicant program selection to inform effective recruitment strategies.

Important limitations should be considered. Although file reviewers were blinded to total application numbers, awareness of national trends may have influenced decisions. As a 4-year program since 2013, our data may not generalize to 3-year programs, though evidence from the Length of Training Pilot suggests that 4-year training does not negatively affect match outcomes.12 On the other hand, our involvement in curricular innovation (now with the Family Medicine Advancing Innovation in Residency Education Project)13 may serve as a recruitment strength,14 which should be considered by other programs. Finally, as this was a single-institution study, broader research across multiple programs is needed to validate these findings.

There are no comments for this article.