Introduction: Teaching graduate medical trainees to conduct forensic medical and mental health evaluations (FMEs) of people seeking asylum fosters knowledge and skills needed to care for displaced and trauma-exposed populations. The national Asylum Medicine Training Initiative (AMTI) is the new standard for training clinicians to conduct FMEs but has not yet been evaluated in graduate medical education.

Methods: We designed a novel, year-long, interdisciplinary, graduate medical elective in asylum medicine that combines AMTI’s asynchronous didactics with experiential learning in the form of small group skills practice and mentored FMEs. We used a formative, mixed-methods approach to evaluate participants’ acquisition of knowledge essential for conducting FMEs, self-reported comfort with relevant skills, and self-reported preparedness for conducting independent FMEs.

Results: Eight trainees participated in the elective from September 2022 to June 2023. The evaluation (response rate 100%, 8/8) showed a significant increase in knowledge essential for conducting FMEs, and most participants felt prepared to conduct FMEs independently. Qualitative analysis showed participants felt they benefited from the experiential learning and that, despite barriers to conducting FMEs, they intend to apply these skills in future work with displaced populations.

Conclusions: Though limited by small sample size and reliance on self-assessment, our results indicate that this novel curriculum helped prepare interdisciplinary trainees to conduct FMEs and improved their comfort with skills applicable to working with displaced populations. This elective could be replicated at other institutions because of the accessibility of the AMTI curriculum and use of virtual space for small groups and mentored FMEs.

As the unprecedented number of displaced persons globally grows, leaders in graduate medical education must prepare trainees to care for these populations.1 Training clinicians to conduct forensic medical and mental health evaluations (FMEs) for people seeking asylum develops competencies essential for working with displaced populations, such as trauma-informed interviewing and examination, cultural competence, and helping them to defend the fundamental human right to asylum.2–10

In an FME, a clinician evaluates an applicant for evidence of alleged persecution and documents their findings in a medico-legal affidavit.2 Traditionally, training involved day-long sessions with expert speakers, though few participants conducted FMEs afterward.11 In 2022, the Asylum Medicine Training Initiative (AMTI)12 sought to improve the existing training paradigm by bringing together 80 stakeholders across more than 40 institutions to create an interdisciplinary, consensus-driven, virtual curriculum that can be paired with experiential learning in a flipped classroom format to better prepare learners.13–15 AMTI has been adopted as the training standard by Physicians for Human Rights, an organization that hosts the largest referral network for pro bono FMEs nationally. However, the AMTI has not been evaluated as a tool in graduate medical education. A few curricula designed to train residents in FMEs have been described,16–18 but they predate the development of the AMTI.

We piloted a year-long, interdisciplinary, graduate medical elective in asylum medicine by pairing AMTI’s curriculum with experiential learning in the form of skills practice and mentored FMEs. Our objectives were to determine if (1) participants acquired knowledge essential for conducting FMEs, (2) participants felt more comfortable with key skills in asylum medicine, and (3) the curriculum helped learners feel prepared to conduct independent FMEs.

Setting and Participants

We piloted the elective at an academic safety-net hospital from September 2022 to June 2023. Our cohort included three internal medicine residents, two family medicine residents, two psychiatry residents, and one clinical psychology postdoctoral fellow. We selected amongst interested trainees by lottery.

Intervention

The elective featured a flipped classroom design informed by experiential learning theory and supported by evidence demonstrating the success of this approach in health professions education.14,19 In semester one, participants independently completed AMTI’s five core modules, then met virtually for four 90-minute small groups (blocks A-D) for skills practice and discussion with faculty experts. In semester two, participants performed three mentored FMEs with increasing independence.

Outcomes Measured

We designed a formative, mixed-methods evaluation to assess knowledge acquisition, skills comfort, and perceived effectiveness in preparing participants to conduct FMEs. The evaluation included surveys at the end of semesters one and two (40-items and 38-items; respectively), a 20-minute semistructured exit interview, and AMTI’s pre-post assessment (68-items).

Surveys and interview questions were developed iteratively with faculty. Questions assessed demographics, prior FME experience, FME skills comfort, elective experience, perceived elective effectiveness, future intentions, and burnout using Likert scales and free-text.

The AMTI assessment was developed iteratively with a national stakeholder working group. Questions assessed demographics, FME knowledge and skills comfort, and direct knowledge acquisition using Likert scales and multiple-choice.

Analyses

We assigned numerical values to Likert questions and compared pre-post change scores using Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests. Knowledge acquisition was assessed using AMTI scores with a paired samples t test for normally distributed data, with significance at P<.05. Free-text responses and interviews were analyzed using a grounded theory approach to develop a codebook. Two researchers double-coded data in Dedoose software (Los Angeles, CA: Sociocultural Research Consultants), systematically identified emerging themes, and resolved discrepancies through consensus. The Cambridge Health Alliance Institutional Review Board approved this study.

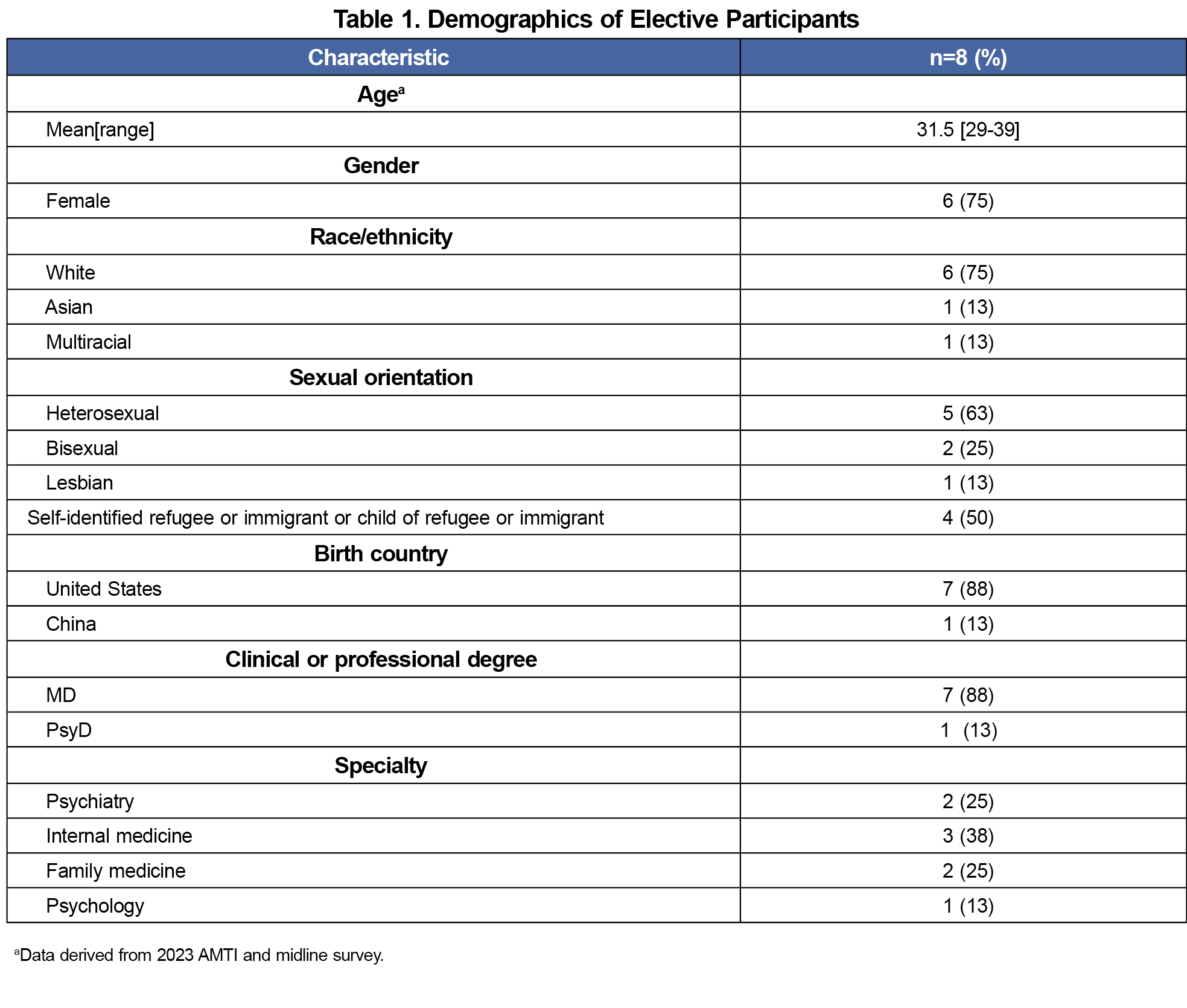

The response rate was 100% (8/8). Half of the participants identified themselves or their parent/guardian(s) as refugees or immigrants, and none had previously conducted a FME (Table 1).

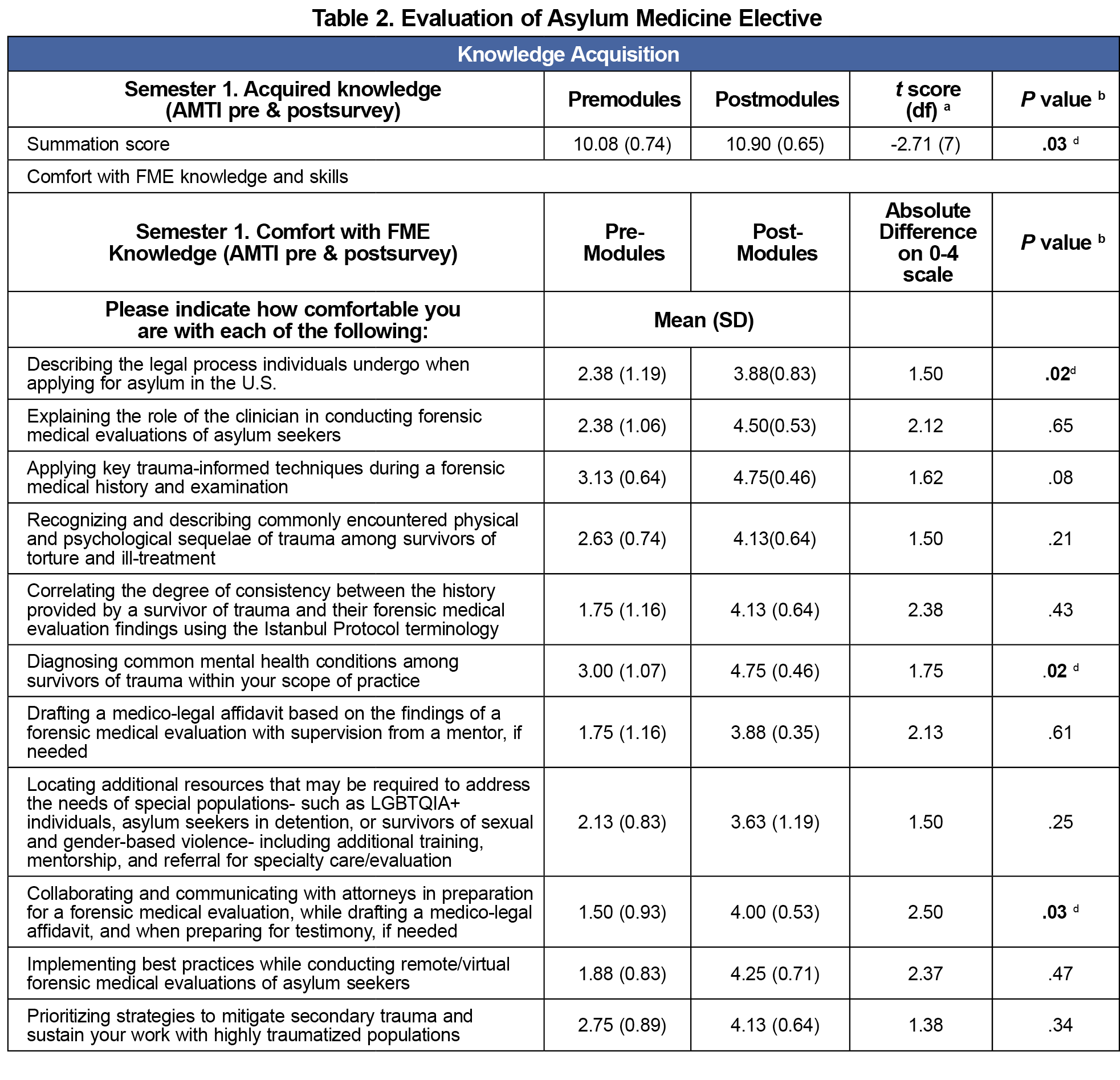

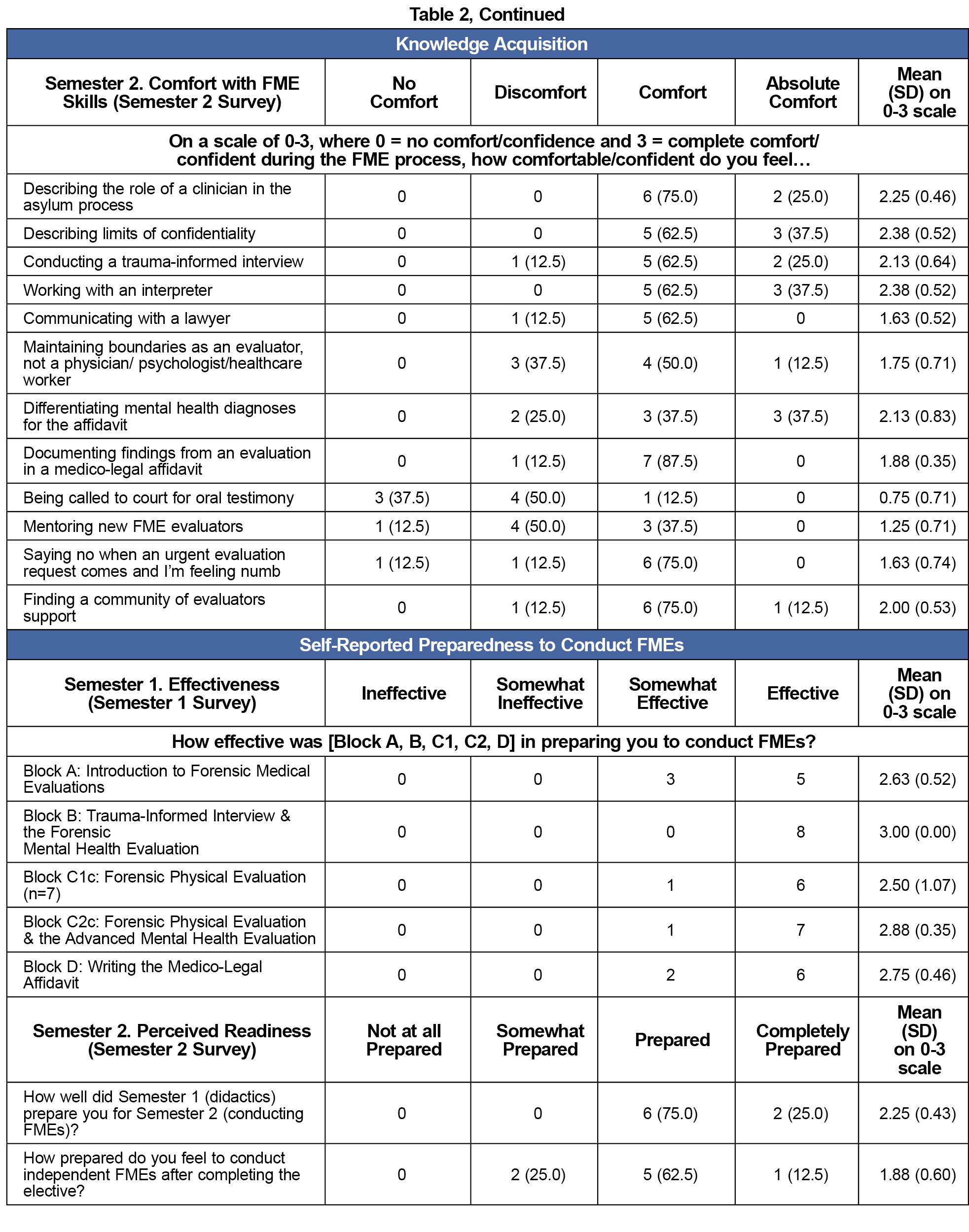

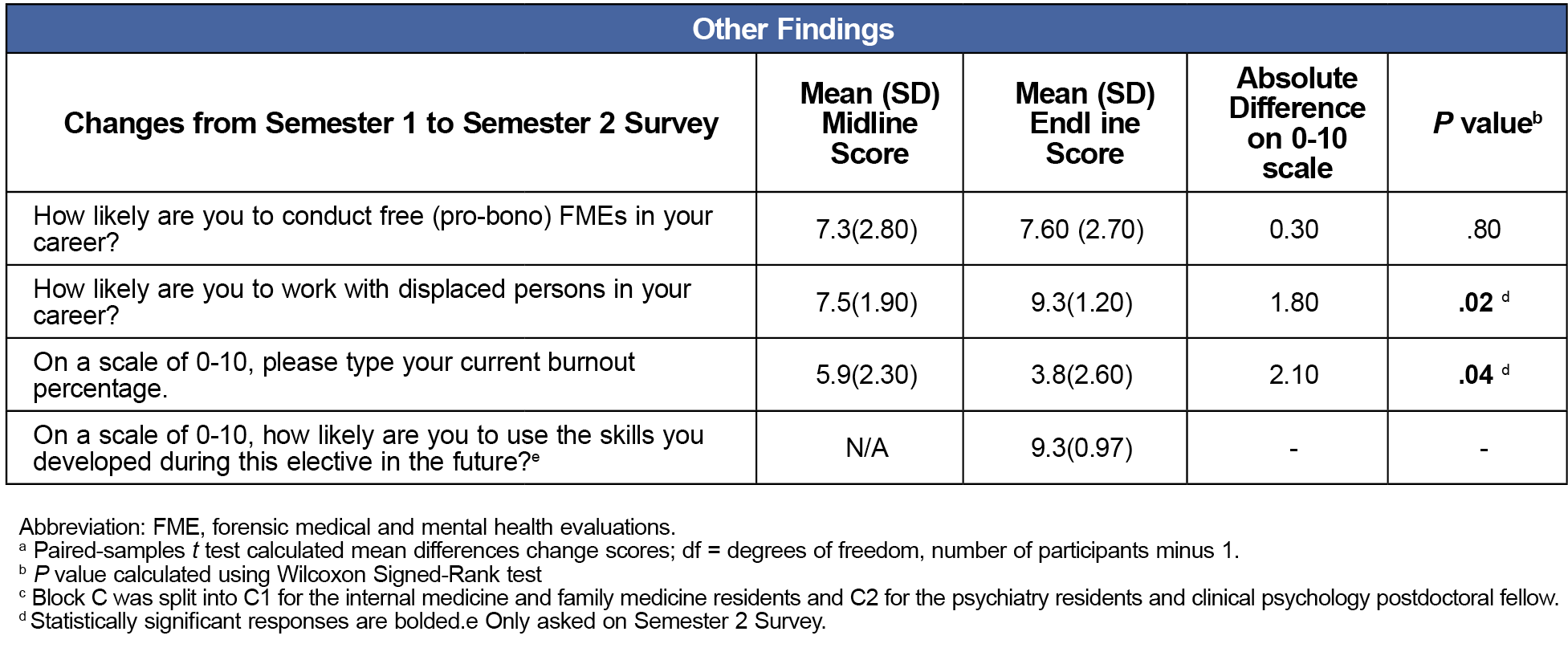

During semester one, AMTI’s direct knowledge assessment revealed a significant increase in knowledge necessary for conducting FMEs. After the elective, participants reported high comfort levels with many key FME skills and 75% (6/8) felt “prepared” or “completely prepared” to conduct FMEs independently. Most participants reported they were likely to use the skills in their future careers and an increased likelihood of working with displaced persons in the future (mean scores: 9.6 and 9.3 on an 11-point scale; Table 2).

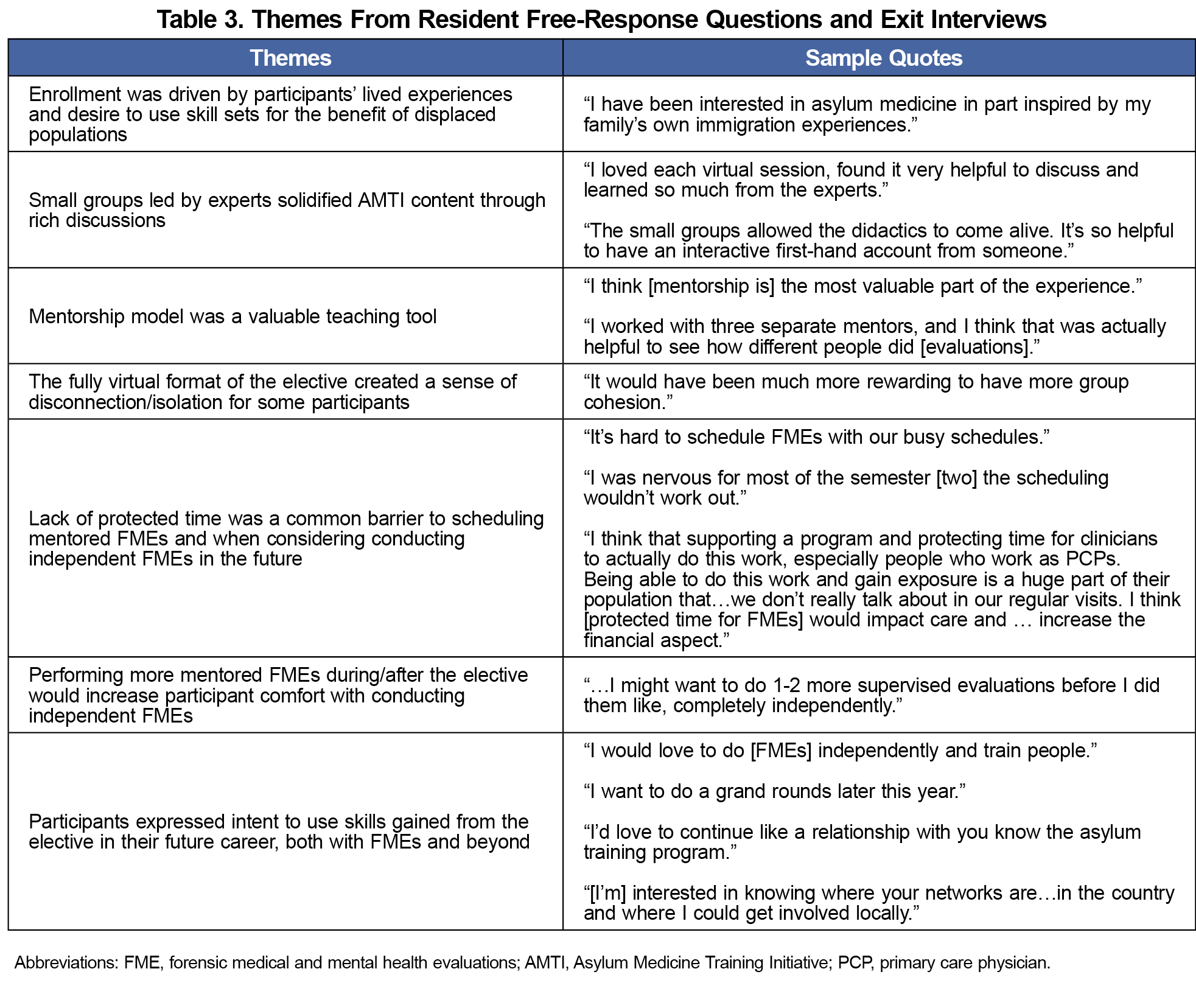

Qualitative analyses revealed seven themes (Table 3). Participants were motivated to participate by their lived experiences and desire to benefit displaced populations. They felt their learning was enhanced by the experiential learning components of the course but desired a stronger sense of community than the fully virtual format created. They identified two barriers to conducting FMEs in the future: lack of protected time and ongoing mentorship. Nevertheless, participants felt they would be able to use the skills acquired in work with displaced populations.

Our study addresses a literature and training gap by presenting a curriculum that integrates AMTI with experiential learning to equip interdisciplinary trainees with essential knowledge for conducting FMEs and enhancing comfort with skills relevant to working with displaced populations. The results of our formative evaluation, though limited by small sample size and a reliance on self-assessment,21 suggest that incorporating experiential learning helped participants feel more comfortable with FME skills and prepared to conduct independent FMEs.9,22

Participants identified lack of protected time and ongoing mentorship as barriers to conducting future FMEs. However, they reported an increased likelihood of working with displaced populations and rated themselves highly likely to use skills learned in the elective, with the potential to decrease burnout.20 Thus, this curriculum has the potential to better equip trainees to deliver general clinical care in today's era of unprecedented migration.23–26

Strengths of this study include the interdisciplinary cohort. Limitations include the small sample size, singular site, and reliance on self-assessment.21 Participants also opted-in, so the results are not generalizable to nonelective contexts. Next steps include direct skills and longitudinal assessments using a larger cohort to determine if/how the skills participants acquired are applied.

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating FME training in graduate medical education using the AMTI curriculum.13 This elective could be replicated at other institutions due to AMTI's accessibility and the use of virtual spaces for small groups and mentored FMEs.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Cambridge Health Alliance Foundation provided financial support for this study.

Conflict Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Presentations:

This study has been presented as follows:

- Kumar A, Santos J, Hahn H, Emery E, Kallivayalil D, Basu G, Snyder S (2023). From a Labor of Love towards a Center of Excellence: Scaling the Cambridge Health Alliance Asylum Program (CHAAP). Presented at Cambridge Health Alliance Academic Poster Session, Somerville, MA.

- Snyder, SA (2024, Mar). Asylum and Mental Health: Increasing Asylum Medicine Awareness & Accessibility. Cambridge Health Alliance | Harvard Medical School. Cambridge, MA.

- Snyder, SA (2023, Nov). Building Capacity, Not Walls: Increasing Asylum Medicine Accessibility & Awareness. Weatherhead Research Cluster on Migration Seminar Series. Harvard University. Cambridge, MA.

- Snyder SA, Wen JX, Kumar A, Kallivayalil D, Emery E (2023, July). Building Capacity, Not Walls: Asylum Medicine Residency Training Elective. North American Refugee Health Conference. Calgary, Canada.

References

- UN Refugee Agency. Global displacement hits another record, capping decade-long rising trend. UNHCR US. Accessed March 16, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/us/news/press-releases/unhcr-global-displacement-hits-another-record-capping-decade-long-rising-trend

- Ferdowsian H, McKenzie K, Zeidan A. Asylum Medicine. Health Hum Rights. 2019;21(1):215-225.

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations. December 10, 1948. Accessed January 29, 2025. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

- Mishori R, Ottenheimer D. Teaching and Learning Asylum Medicine. In: McKenzie KC, ed. Asylum Medicine.Springer International Publishing; 2022:153-161, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-81580-6_11.

- McKenzie KC, Emery EH. Lessons from asylum seekers: how forensic medical evaluations can teach us things we didn’t learn in medical school. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):2121-2122. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06157-7

- Baranowski KA, Moses MH, Sundri J. Supporting asylum seekers: clinician experiences of documenting human rights violations through forensic psychological evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(3):391-400. doi:10.1002/jts.22288

- Singer E, Eswarappa M, Kaur K, Baranowski KA. Addressing the need for forensic psychological evaluations of asylum seekers: the potential role of the general practitioner. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112752. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112752

- Jaradeh K, Sergi F, Kivlahan C, Nava Gonzales C, Cury M, DeFries T. Implementing a trauma-informed approach at a student-run clinic for individuals seeking asylum. Acad Med. 2023;98(3):332-336. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005064

- Rezaei SJ, Twardus S, Collins M, Gartland M. Utilizing a participatory curriculum development approach for multidisciplinary training on the forensic medical evaluation of asylum seekers. J Forensic Leg Med. 2024;105:102718. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2024.102718

- McKenzie KC, Mishori R, Ferdowsian H. Twelve tips for incorporating the study of human rights into medical education. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):871-879. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1623384

- Gu F, Chu E, Milewski A, et al. Challenges in founding and developing medical school student-run asylum clinics. J Immigr Minor Health. 2021;23(1):179-183. doi:10.1007/s10903-020-01106-2

- Emery E, DeFries T. Asylum medicine training initiative: asylum medicine introductory curriculum. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://asylummedtraining.org

- Green A, Emery E, Shadid O, Gartland M, Saadi A. Applied learning in advanced asylum medicine: piloting experiential learning in forensic medical evaluations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2025;27(1):171-176. doi:10.1007/s10903-024-01642-1

- Hew KF, Lo CK. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):38. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z

- PHR Trainings and Webinars for Health Professionals. Physicians for Human Rights. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://phr.org/issues/asylum-and-persecution/asylum-network-trainings/

- Metalios EE, Asgary RG, Cooperman N, et al. Teaching residents to work with torture survivors: experiences from the Bronx Human Rights Clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1038-1042. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0592-2

- Asgary R, Saenger P, Jophlin L, Burnett DC. Domestic global health: a curriculum teaching medical students to evaluate refugee asylum seekers and torture survivors. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):348-357. doi:10.1080/10401334.2013.827980

- Jelousi S, Montejano D, Jaradeh K, Kivlahan C, Shinkai K, Chang AY. Evaluation of a pilot forensic dermatology curriculum in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(12):2296-2298. doi:10.1111/ced.15380

- Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102-e115. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.650741

- De Marchis E, Knox M, Hessler D, et al. Physician burnout and higher clinic capacity to address patients’ social needs. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(1):69-78. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.01.180104

- Morley CP. Moving on from self-assessment. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2024;8:5. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2024.624901

- Kwok MJJ, Jacob W. Framework for implementing asylum seekers and refugees’ health into the undergraduate medical curriculum in the United Kingdom. Health Educ Res. 2024;39(2):170-181. doi:10.1093/her/cyae002

- Council on Foreign Relations. Migration Today. CFR Education from the Council on Foreign Relations. October 19, 2024. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://education.cfr.org/learn/reading/migration-today

- Connell BJ, Shin AJ. Fed up: the global ascension of the federal reserve in the era of migration. Int Stud Q. 2023;67(2):sqad029. doi:10.1093/isq/sqad029

- UN Refugee Agency. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023. Published online June 13, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2023

- Mohammadi M, Jafari H, Etemadi M, et al. Health problems of increasing man-made and climate-related disasters on forcibly displaced populations: a scoping review on global evidence. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2023;17:e537. doi:10.1017/dmp.2023.159

There are no comments for this article.