Following recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) during the COVID-19 pandemic, graduate medical education (GME) residency programs transitioned to virtual interviews for the 2020-2021 application cycle.1 Since then, studies have highlighted benefits including time efficiency and cost savings, alongside barriers such as technological access.2,3 Given the high cost of American medical education, interview expenses are a significant challenge for applicants.4,5 Although traditional interview costs vary, digital formats have helped reduce some financial burdens.6-10 Nonetheless, there are limited data linking medical students’ debt concern with their experiences of interview formats. We hypothesized students with higher debt concerns would favor virtual interview offers and recommend them for future cycles.

RESEARCH BRIEF

Associations Between Family Medicine Residency Applicants’ Debt Concern and Their Perception of Virtual Residency Interviews

Srilakshmi P. Vankina, BA | Radhika Laddha, BS | Alison N. Huffstetler, MD

PRiMER. 2025;9:15.

Published: 4/18/2025 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2025.898068

Introduction: Since the shift to virtual residency interviews following the COVID-19 pandemic and the initial 2021 and 2022 endorsement from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, applicants and programs have been weighing the benefits and disadvantages of this transition. This study examines the impact of debt concern among family medicine residency applicants and their likelihood of (1) accepting virtual interview offers and (2) recommending the digital format for future application cycles.

Methods: Using responses from the American Academy of Family Physicians 2023 Medical Student Education Survey, we applied descriptive bivariate analysis and rapid cycle thematic evaluation to explore associations between 2023 family medicine residency applicants’ debt concern and their perception of digital residency interviews.

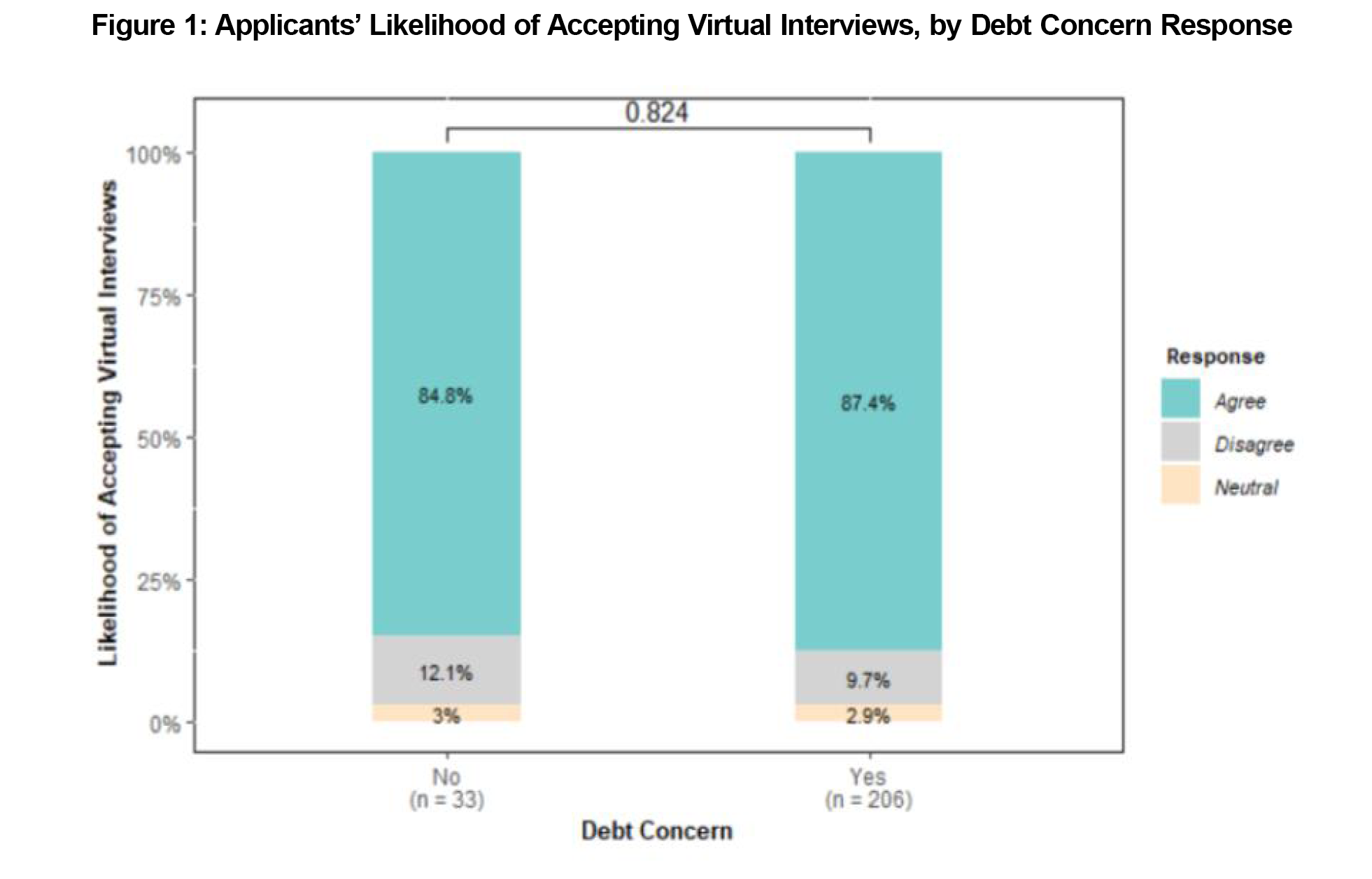

Results: A majority of our study sample (86%) had some level of debt concern. A majority (88.8%) also noted that most of their interviews were virtual. Regardless of debt concern, most students (87.4%) indicated that they accepted offers for virtual interviews that they otherwise may not have accepted if travel time and expenses were involved. Furthermore, most students (87.1%) recommended a virtual component to future residency interviews.

Conclusion: Contrary to our expectations, there was no association between concern for debt and preference for virtual interviews. Most candidates preferred the virtual setting, stating that they were more likely to accept virtual interview offers, and recommended this format for future cycles.

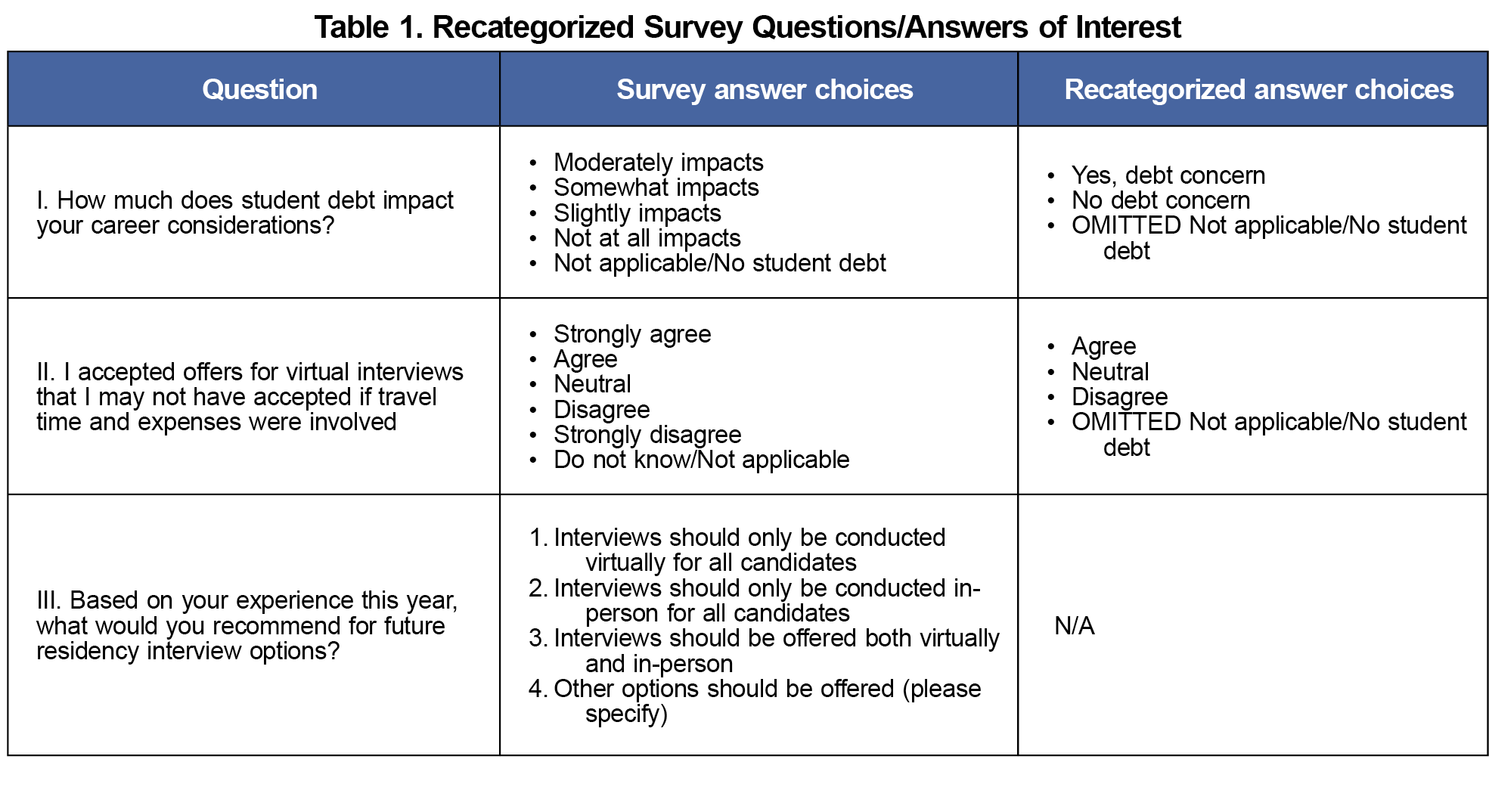

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) Institutional Review Board determined this study to be exempt from review. Using quantitative and qualitative responses from the AAFP 2023 Medical Student Education Survey, we explored associations between applicants’ debt concern and perception of digital residency interviews.11 The AAFP medical education team compiled a 50-item survey through an inductive process with the goals of (1) examining students’ perspectives on family medicine and the AAFP, and (2) identifying ways to better help applicants navigate the residency Match process. The survey was emailed to all 2023 AAFP student members with valid email addresses. If there was no response, two follow-up reminders were sent via a modified Dillman method.12 In addition to demographic questions, the survey covered several topics: Family Medicine Attitudes Questionnaire (FMAQ), AAFP membership and resources, specialty choice, student debt, the match process, and student needs. We focused our study sample on those who applied to match in 2023 and answered questions relating to personal debt and virtual interviews, as recategorized in Table 1. We compared our study sample to the demographics of overall 2023 ERAS applicants using χ2 goodness-of-fit test. We analyzed relationships between applicants’ debt concern and perception of virtual interview formats using descriptive bivariate analysis. Through rapid cycle thematic evaluation, one reviewer examined each open-ended response and categorized them based on evolving themes related to financial barriers and interview formats. Two to three rounds of review ensured consistency and alignment with these themes.

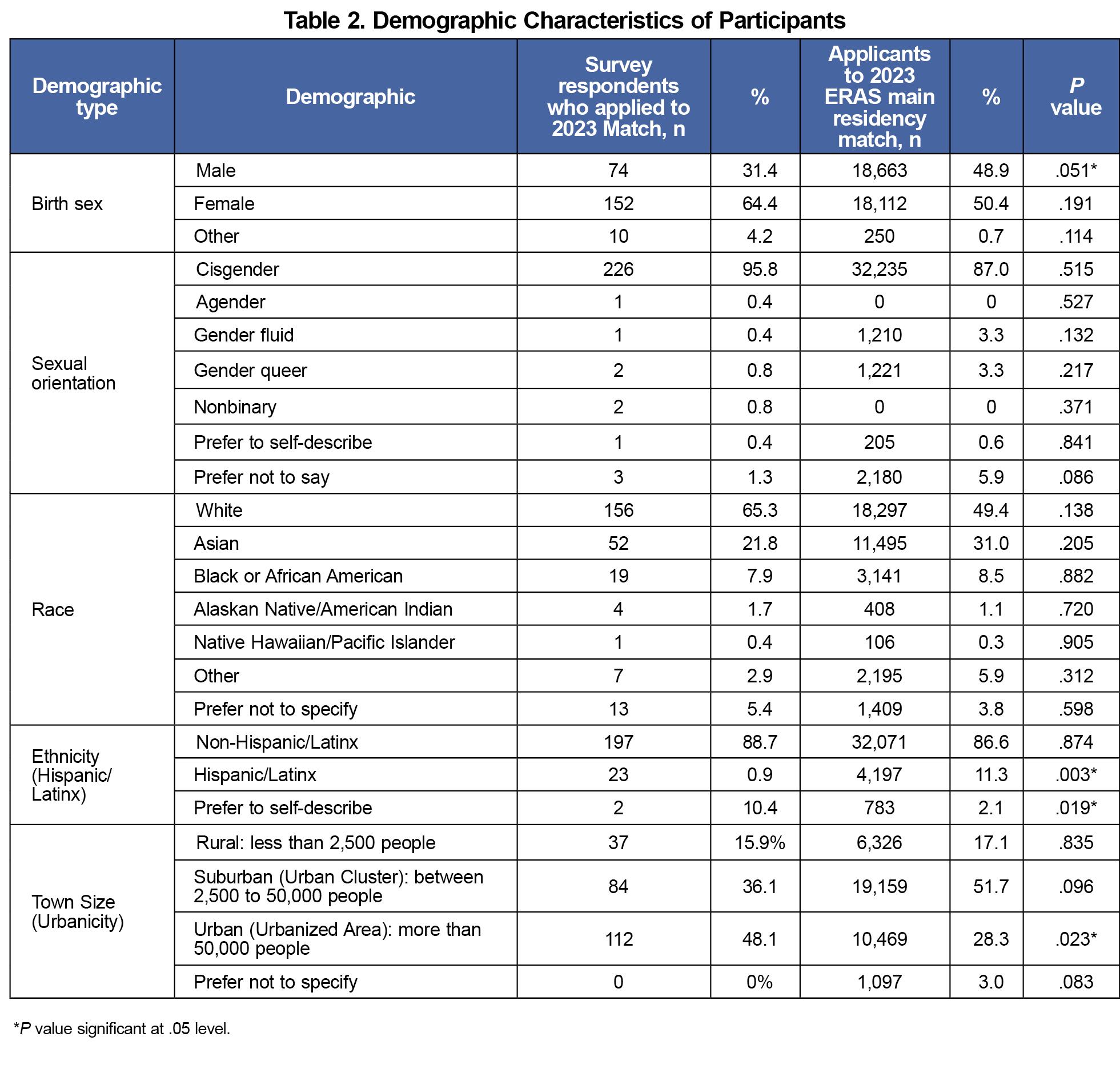

The survey was emailed to 20,585 AAFP student members with a 6.0% response rate, resulting in 1,225 replies. Of the total respondents, 294 participated in the 2023 match. After omitting 32 “not applicable or no student debt” responses for Question I. and 20 “do not know or not applicable” responses for Question II, our final sample size of 239 only included those that answered the study’s questions of interest. When comparing our study population to the demographics of the 42,908 overall ERAS applicants in 2023, our sample had a smaller proportion of male applicants (31.4% vs 48.9%, P=.051), smaller proportion of Hispanic applicants (0.9% vs 11.3%, P=0.003), greater proportion of applicants who prefer to self-describe their ethnicity (10.4% vs. 2.1%, P=.019), and greater representation from urban areas (48.1% vs 28.3%, P=.023, Table 2).13 A majority of our study sample (86%) had some level of debt concern (Question I categorized as slightly, somewhat, or moderately impacts), and most (88.8%) also noted that a majority of their interviews were virtual.

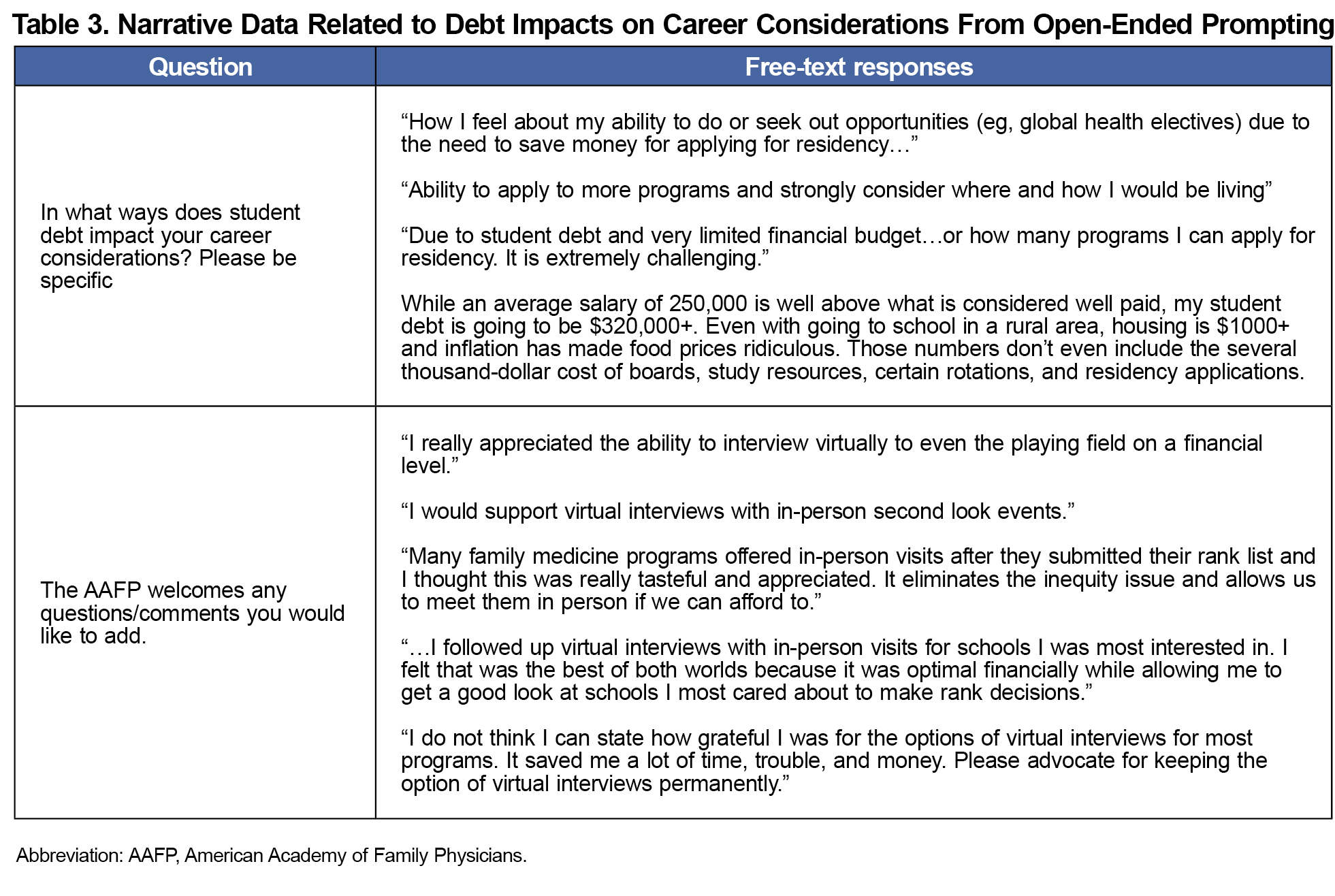

Contrary to expectations, there was no association between debt concern and digital interview preference. Most candidates preferred the virtual format. Regardless of debt concern, most students (87.4%) accepted virtual interview offers that they may not have otherwise due to time and expenses (Figure 1). Additionally, 87.1% recommended a virtual component to future residency interviews. Covariates of sex (P=.006) and MD/DO degree (P=.031) were associated interview format preferences, while race (P=.443) was not. While most accepted virtual interviews, 64.8% also highlighted the importance of visiting programs of interest in-person. Several applicants provided free-response narrative feedback related to debt impacts on career considerations (Table 3). Students described the financial burdens of medical training and how it limited their ability to apply and interview widely. Some appreciated how digital residency interviews reduced financial barriers and noted that in-person second look events were also helpful.

Irrespective of debt concern, virtual residency interview formats are important to students and offer more flexibility within an already expensive and time-consuming process.14-18 This study suggests that factors beyond medical school debt alone may influence applicants’ preference for and recommendation of virtual interviews.

Existing literature supports our study’s narrative feedback, citing cost alleviation, time efficiency, accessibility, and equity as benefits of virtual interviews.19-26 The pervasive fear of not matching also likely plays a role, as online formats offer more feasibility, leading to increased applications.27-30 However, despite reduced costs and application inflation with digital interviews, our data highlight that the financial burden of medical education still limits how broadly applicants apply and interview.

Programs have enhanced virtual interview days with more social engagement, but applicants do still value in-person second look days before finalizing their rank lists. This suggests that students are cognizant of program fit and find in-person days beneficial for decision-making.31-32 However, unless residency programs standardize this process, expand financial accessibility, and ensure that attendance will not impact rank orders, inequity remains.33-37

Our study has limitations, including a low survey response rate resulting in an underwhelming sample size, with some significant demographic differences compared to overall ERAS applicants. Although varied, most email survey response rates are about 25%, possibly influenced by factors such as survey length and postpandemic survey fatigue.38-40 AAFP membership trends also help contextualize this sample. Although many students obtain AAFP membership for a variety of resources, internal tracking show that 11%-17% of student members go on to become resident members. Additionally, debt concern may not accurately reflect financial stressors and does not account for actual debt burden. Variations in debt levels, generational and cultural wealth, and first-generation medical student status, may influence debt perception and residency decisions.41-44

Future studies should better quantify debt burden and incorporate more narrative feedback to understand interview preferences. Residency program directors should weigh applicants’ concerns and preferences in an overburdened application process, while prioritizing equity throughout.

References

- Coalition for Physician Accountability. Final Report and Recommendations for Medical Education Institutions of LCME-Accredited, U.S. Osteopathic, and Non-U.S. Medical School Applicants. AAMC; 2021. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/media/44731/download

- Domingo A, Rdesinski RE, Cheng A, et al. Effectiveness of virtual residency interviews: interviewer perspectives. Fam Med. 2022;54(10):828-832. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.177754

- Domingo A, Rdesinski RE, Stenson A, et al. Virtual residency interviews: applicant perceptions regarding virtual interview effectiveness, advantages, and barriers. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(2):224-228. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00675.1

- Fried J. Cost of applying to residency questionnaire report. AAMC. 2015. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/media/24826/download

- Seifi A, Mirahmadizadeh A, Eslami V. Perception of medical students and residents about virtual interviews for residency applications in the United States. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0238239. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238239

- Fogel HA, Liskutin TE, Wu K, Nystrom L, Martin B, Schiff A. The economic burden of residency interviews on applicants. Iowa Orthop J. 2018;38:9-15.

- Guidry J, Greenberg S, Michael L. Costs of the residency match for fourth-year medical students. Tex Med. 2014;110(6):e1.

- Rohrberg T, Walling A, Gillam M, St Peter M, Nilsen K. Interviewing for family medicine residency: in-person, virtual, or hybrid? Fam Med. 2022;54(10):820-827. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.951860

- Edje L, Miller C, Kiefer J, Oram D. Using Skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):503-505. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-12-00152.1

- Shah SK, Arora S, Skipper B, Kalishman S, Timm TC, Smith AY. Randomized evaluation of a web based interview process for urology resident selection. J Urol. 2012;187(4):1380-1384. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.108

- AAFP Medical Student Survey (2023). STFM Resource Library. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://connect.stfm.org/connections/community-home/librarydocuments/viewdocument?DocumentKey=6f5f8f47-b00b-4ffe-a53b-0191480658ad&CommunityKey=90cceb35-312d-4bba-b27a-695f2da1f418&tab=librarydocuments

- Hoddinott SN, Bass MJ. The Dillman total design survey method. Can Fam Physician. 1986;32:2366-2368.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2023 Main Residency Match.National Resident Matching Program; 2023. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2023-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Book-FINAL.pdf

- Callaway P, Melhado T, Walling A, Groskurth J. Financial and time burdens for medical students interviewing for residency. Fam Med. 2017;49(2):137-140.

- Greysen SR, Chen C, Mullan F. A history of medical student debt: observations and implications for the future of medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(7):840-845. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821daf03

- Wyatt TR, Casillas A, Webber A, Parrilla JA, Boatright D, Mason H. The maintenance of classism in medical education: “time” as a form of social capital in first-generation and low-income medical students. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2024;29(2):551-566. doi:10.1007/s10459-023-10270-7

- Badiee RK, Hernandez S, Valdez JJ, NnamaniSilva ON, Campbell AR, Alseidi AA. Advocating for a new residency application process: A Student Perspective. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(1):20-24. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.07.018

- Kraft DO, Bowers EMR, Smith BT, et al. Applicant perspectives on virtual otolaryngology residency interviews. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2022;131(12):1325-1332. doi:10.1177/00034894211057374

- Nilsen K, Callaway P, Phillips JP, Walling A. How much do family medicine residency programs spend on resident recruitment? A CERA study. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):405-412. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.663971

- Wright AS. Virtual interviews for fellowship and residency applications are effective replacements for in-person interviews and should continue post-COVID. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(6):678-680. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.09.005

- Davis MG, Haas MRC, Gottlieb M, House JB, Huang RD, Hopson LR. Zooming in versus flying out: virtual residency interviews in the era of COVID-19. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(4):443-446. doi:10.1002/aet2.10486

- Hanes JE, Waserman JL, Clarke QK. The accessibility of virtual residency interviews: the good, the bad, the solutions. Can Med Educ J. 2022;13(2):98-100. doi:10.36834/cmej.74107

- Richard K, Chiel L, Kazmerski TM, et al. Virtual interviews and equity: the pediatric pulmonary fellow perspective. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2024;59(6):1731-1739. doi:10.1002/ppul.26983

- Do Tran A, Heisler CA, Botros-Brey S, et al. Virtual interviews improve equity and wellbeing: results of a survey of applicants to obstetrics and gynecology subspecialty fellowships. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):620. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03679-y

- Nguyen JK, Moran SK, Yee JM, Grimm LJ, Heitkamp DE, Chapman T. Moving towards equity, wellness, and environmental sustainability: arguments for virtual radiology residency recruitment and strategies for application control. Acad Radiol. 2022;29(7):1124-1128. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2021.12.014

- Heitkamp NM, Snyder AN, Ramu A, et al. Lessons learned: applicant equity and the 2020-2021 virtual interview season. Acad Radiol. 2021;28(12):1787-1791. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2021.08.005

- Association of American Medical Colleges. ERAS Statistics by Applicant: Family medicine. 2022. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/media/39346/download

- Meyer AM, Hart AA, Keith JN. COVID-19 Increased residency applications and how virtual interviews impacted applicants. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e26096. doi:10.7759/cureus.26096

- Frame KA, Fortenberry KT, Cochella S, et al. Impact of virtual recruitment on costs, time spent, and applicant perspectives within a family medicine residency program. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2023;7:38. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2023.262017

- Antono B, Willis J, Phillips RL Jr, Bazemore A, Westfall JM. The price of fear: an ethical dilemma underscored in a virtual residency interview season. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(3):316-320. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-01411.1

- Moran SK, Nguyen JK, Grimm LJ, et al. Should radiology residency interviews remain virtual? Results of a multi-institutional survey inform the debate. Acad Radiol. 2022;29(10):1595-1607. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2021.10.017

- Hays A, Khare M, Pluta D, Verzal R, Garry JP. First-year resident perceptions of virtual interviewing. Fam Med. 2022;54(10):814-819. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.364201

- Wilson LT, Milliken L, Cagande C, Stewart C. Responding to recommended changes to the 2020-2021 residency recruitment process from a diversity, equity, and inclusion perspective. Acad Med. 2022;97(5):635-642. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004361

- England E, Kanfi A, Tobler J. In-person second look during a residency virtual interview season: an important consideration for radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol. 2023;30(6):1192-1199. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2022.07.015

- Mauricio EA, Coon EA, Driver-Dunckley ED, et al; for Mayo Clinic adult neurology residency program leadership. education research: virtual residency interviews and the second look: the Mayo Clinic neurology tri-site experience. Neurol Educ. 2023;2(4):e200095. doi:10.1212/NE9.0000000000200095

- Hampshire K, Shirley H, Teherani A. Interview without harm: reimagining medical training’s financially and environmentally costly interview practices. Acad Med. 2023;98(2):171-174. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005000

- Transition to Residency. ACOG. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/creog/transition-to-residency

- Fincham JE. Response rates and responsiveness for surveys, standards, and the Journal. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):43. doi:10.5688/aj720243

- Sheehan K. E-mail survey response rates: A review. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2001;6(2):0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00117.x

- de Koning R, Egiz A, Kotecha J, et al. Survey fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of neurosurgery survey response rates. Front Surg. 2021;8:690680. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2021.690680

- Rajapuram N, Langness S, Marshall MR, Sammann A. Medical students in distress: the impact of gender, race, debt, and disability. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12 December). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0243250

- Pisaniello MS, Asahina AT, Bacchi S, et al. Effect of medical student debt on mental health, academic performance and specialty choice: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e029980. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029980

- Thomas A. Exploring the Community Cultural Wealth of Black Medical Students Who Completed Post-baccalaureate Study Prior to Admissions: A Narrative Study.Drexel University; 2022.

- Fokas JA, Coukos R. Examining the hidden curriculum of medical school from a first-generation student perspective. Neurology. 2023;101(4):187-190. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000207174

Lead Author

Srilakshmi P. Vankina, BA

Affiliations: University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN

Co-Authors

Radhika Laddha, BS - Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, Washington, DC

Alison N. Huffstetler, MD - Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, Washington, DC

Corresponding Author

Srilakshmi P. Vankina, BA

Correspondence: University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN

Email: vanki008@umn.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.