Introduction: Underrepresented in family medicine (URiFM) physicians hold 14.42% of US family medicine faculty positions. Scholarship is critical to academic advancement. We explored family medicine department chairs’ racial allyship, their identification of scholarship barriers faced by URiFM faculty, and the existence of initiatives to increase scholarship.

Methods: We used the 2022 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) Department Chair survey to examine the percentage of chair-perceived URiFM departmental faculty members and their scholarly productivity and chair-perceived barriers to productivity and initiatives. We measured chairs’ racial allyship. We calculated descriptive statistics, weighted means, and used regression to identify whether chair characteristics or allyship scores were associated with support of URiFM faculty scholarship initiatives and identification of the minority tax.

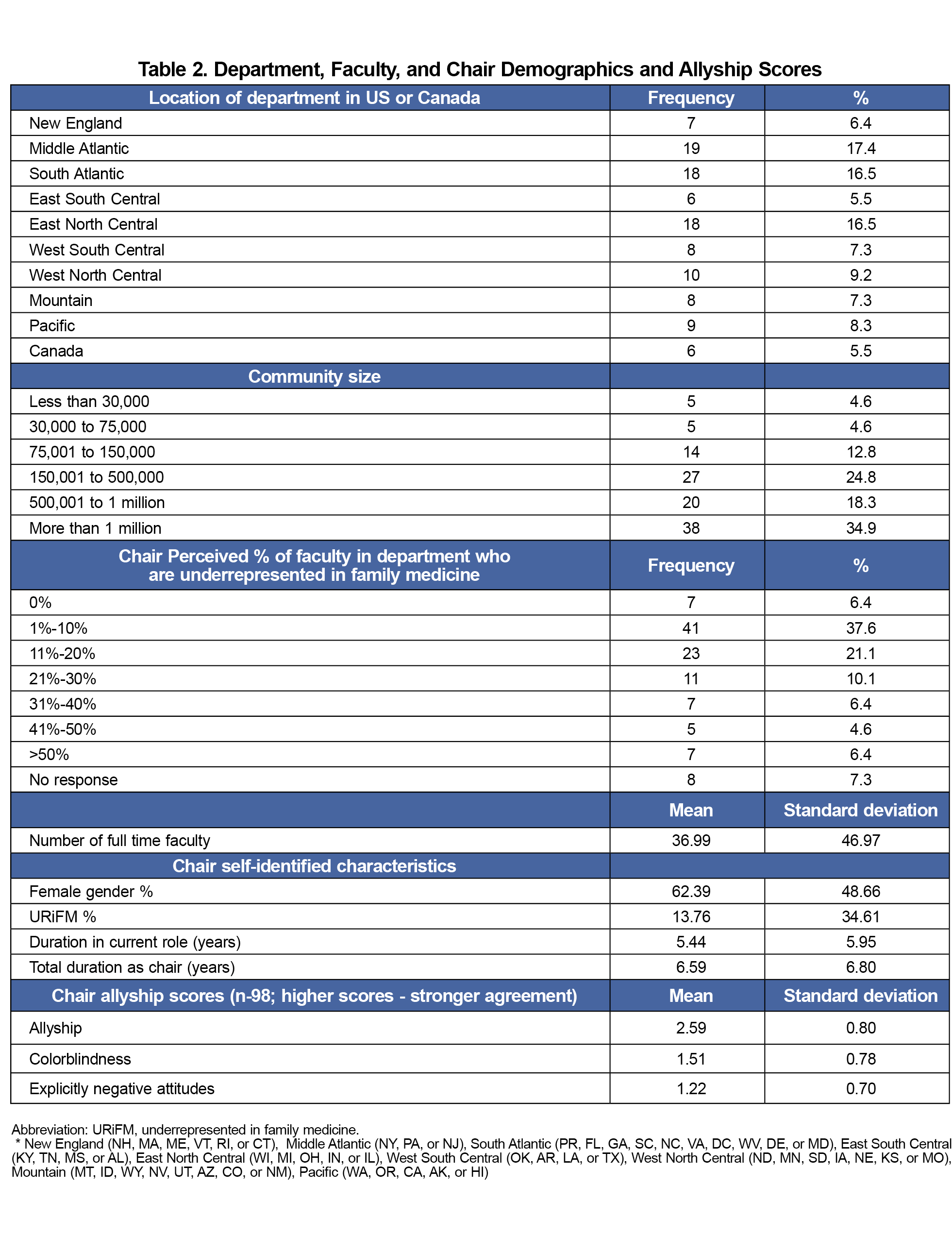

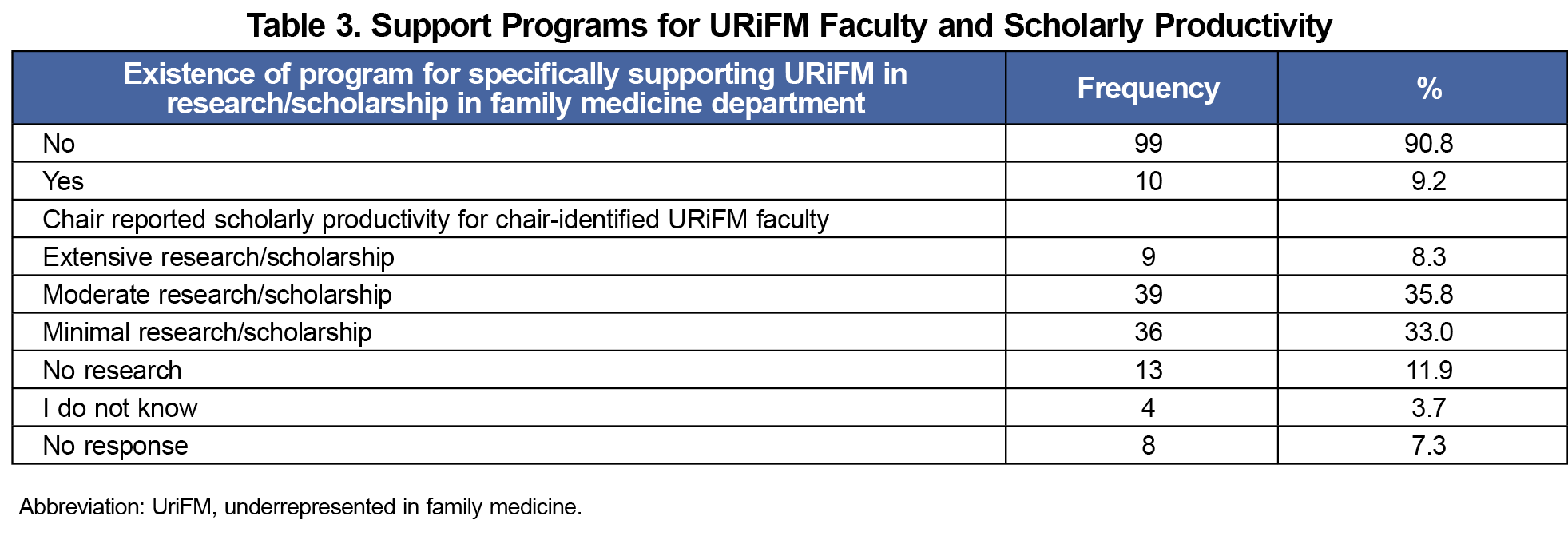

Results: One hundred nine chairs completed the survey (response rate 48.4%); 13.76% identified as URiFM; 6.4% reported they perceived more than 50% of their faculty were URiFM; 90.8% of chairs did not report programs supporting URiFM scholarship; and 44.9% described URiFM faculty scholarly output as minimal or none. Department chairs’ mean allyship score was 2.59 (SD = 0.80) out of 5. Chairs ranked lack of research skills and lack of funding for protected time higher than the minority tax from a list of scholarship barriers. We found no association between chair allyship scores, chair characteristics, total department full-time equivalents, and the existence of a URiFM faculty scholarly support program.

Discussion: Despite chairs reporting low URiFM faculty scholarly output, few departments have a dedicated support program. Chair allyship scores were not associated with identification of scholarship barriers or existence of scholarship programs.

Among underrepresented in medicine (URiM) faculty, including those who identify as Black or African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or Hispanic or Latina/o, representation remains low at 14.42% compared to 41.6% of the US population identifying as a race or ethnicity other than White.1-3 Although the term “underrepresented in medicine” (URiM) has been widely cited and is commonly attributed to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), a formal definition is no longer available on a public webpage. As an adaptation of this term, throughout this paper we use underrepresented in family medicine (URiFM) to specifically denote physicians from these groups within the academic family medicine workforce.

Scholarship productivity is essential for academic promotion, yet URiFM faculty face unique barriers including inadequate mentoring, discrimination and the minority tax. Here, “minority tax” is defined as the expectation that URiFM faculty lead diversity efforts, mentor minority learners, and serve as diversity representatives, while these activities rarely count toward promotion.4-5 Given the documented impact of the minority tax on URiFM faculty advancement, we elected to examine this variable as an exploratory aim to assess whether chairs who demonstrate higher allyship are more likely to recognize this as a specific barrier. Department leadership support is fundamental to faculty research success. Racial allyship—a situation in which a person in a position of power works in solidarity with marginalized groups to address racial injustice—may be critical for URiFM faculty advancement.6-7 However, the role of department chair allyship in supporting URiFM scholarship remains unexplored.8-9

Our study aimed to (1) characterize department chairs' racial allyship and existing URiFM faculty in family medicine scholarship support programs, (2) identify chairs' perceived barriers to URiFM productivity and initiatives, and (3) examine associations between chair allyship and both their recognition of the minority tax as a barrier and the existence of programs to increase URiFM productivity in their departments.

Chair recognition of the minority tax may change the way departments are structured or the criteria for promotion and increase URiFM production indirectly. Chairs also can implement programs to directly increase URiFM scholarship. Racial allyship may be a quality that improves URiFM scholarship in a department.

We collected data through the 2022 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) Department Chairs survey, conducted in August and September 2022.10 After excluding six individuals no longer serving as chairs, the final sampling frame included 225 department chairs (208 United States,17 Canadian). The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved this study.

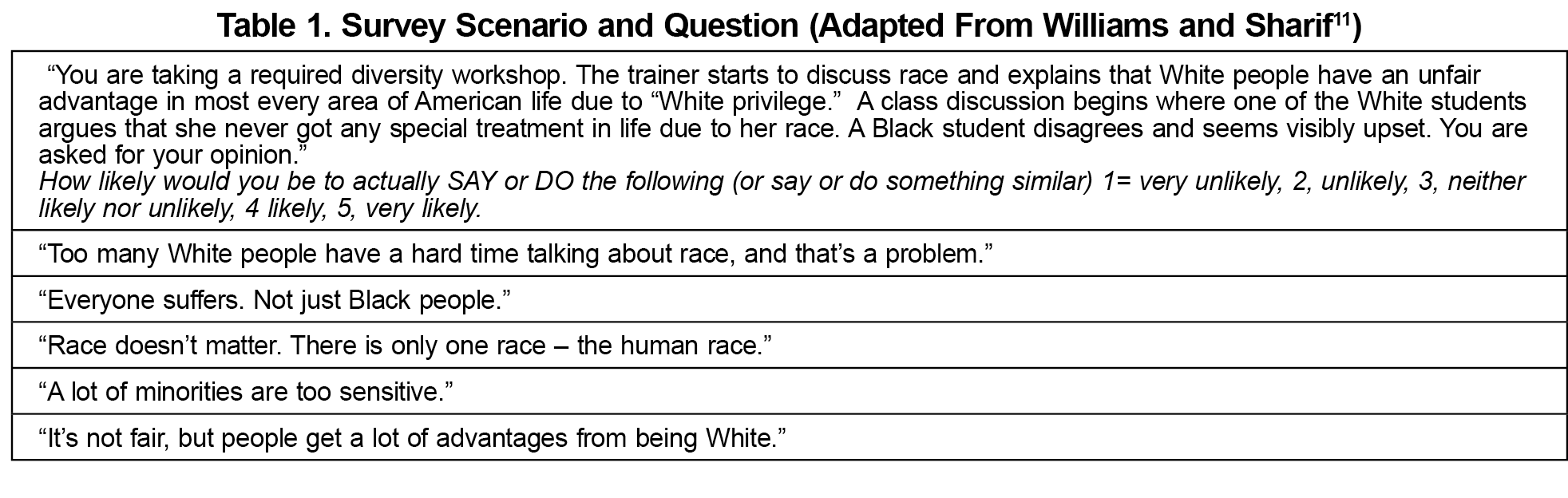

This cross-sectional survey included standard recurring CERA demographic questions, and items specific to chair-perceived URiFM departmental representation, chair-perceived URiFM scholarly output, support programs for URiFM scholarly activity, perceived barriers, and an adapted version of a validated racial allyship instrument (Table 1).11 The original instrument included eight different scenarios with 44 different statements to respond to, a length that was impossible to replicate because this survey was part of a larger national survey limited to 10 total items. We selected the scenario chairs were most likely to have experience with (a diversity training) and that captured three different constructs. This adaptation may limit construct validity compared to the full instrument. However, the constraints of the CERA survey necessitated this approach. We calculated an allyship score (readiness to act in solidarity with racially marginalized individuals) from the mean of responses to the first (a) and fifth (e) statements, a colorblindness score (tendency to downplay the significance of race or systemic racism) by the mean of responses of the second (b) and third (c) statements, and an explicitly negative attitudes score (overt prejudice that blames or disparages minoritized groups) from the response to the fourth (d) statement. Because a Likert scale is used, higher values suggest stronger agreement or endorsement of each construct.

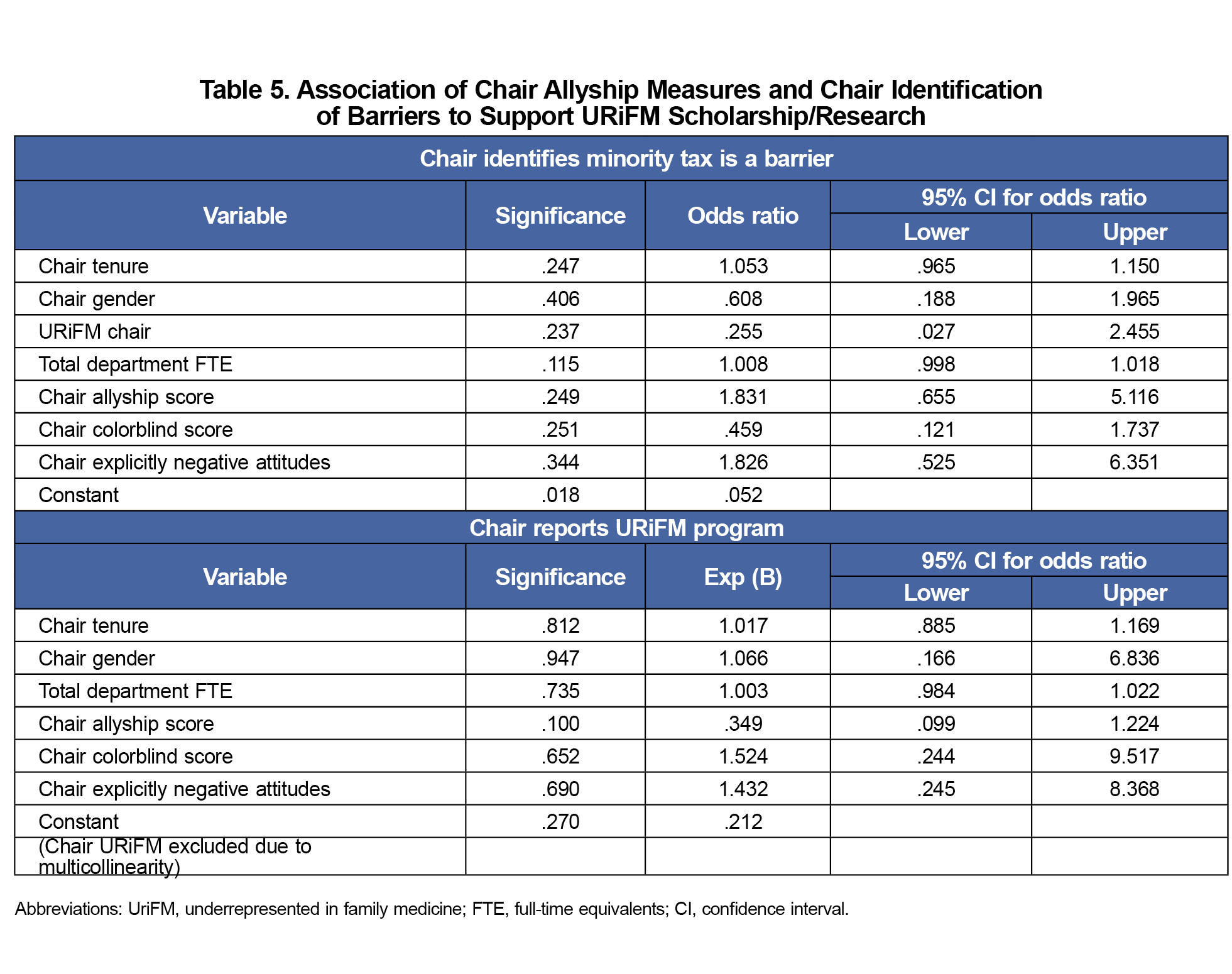

We used descriptive statistics to characterize departments, chair characteristics, existing support programs, and scholarly productivity. We calculated weighted ranks for chair-perceived barriers to URiFM scholarly productivity and barriers to initiatives to support productivity. Two logistic regression analyses, adjusted for total faculty full-time equivalents (FTE), chair gender, chair URiFM status, and chair tenure, examined the association between allyship scores and recognition of the minority tax as a barrier and the presence of a URiFM scholarship program. We conducted all analyses using SPSS software, version 29 (IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was set to α=0.05 (two-tailed).

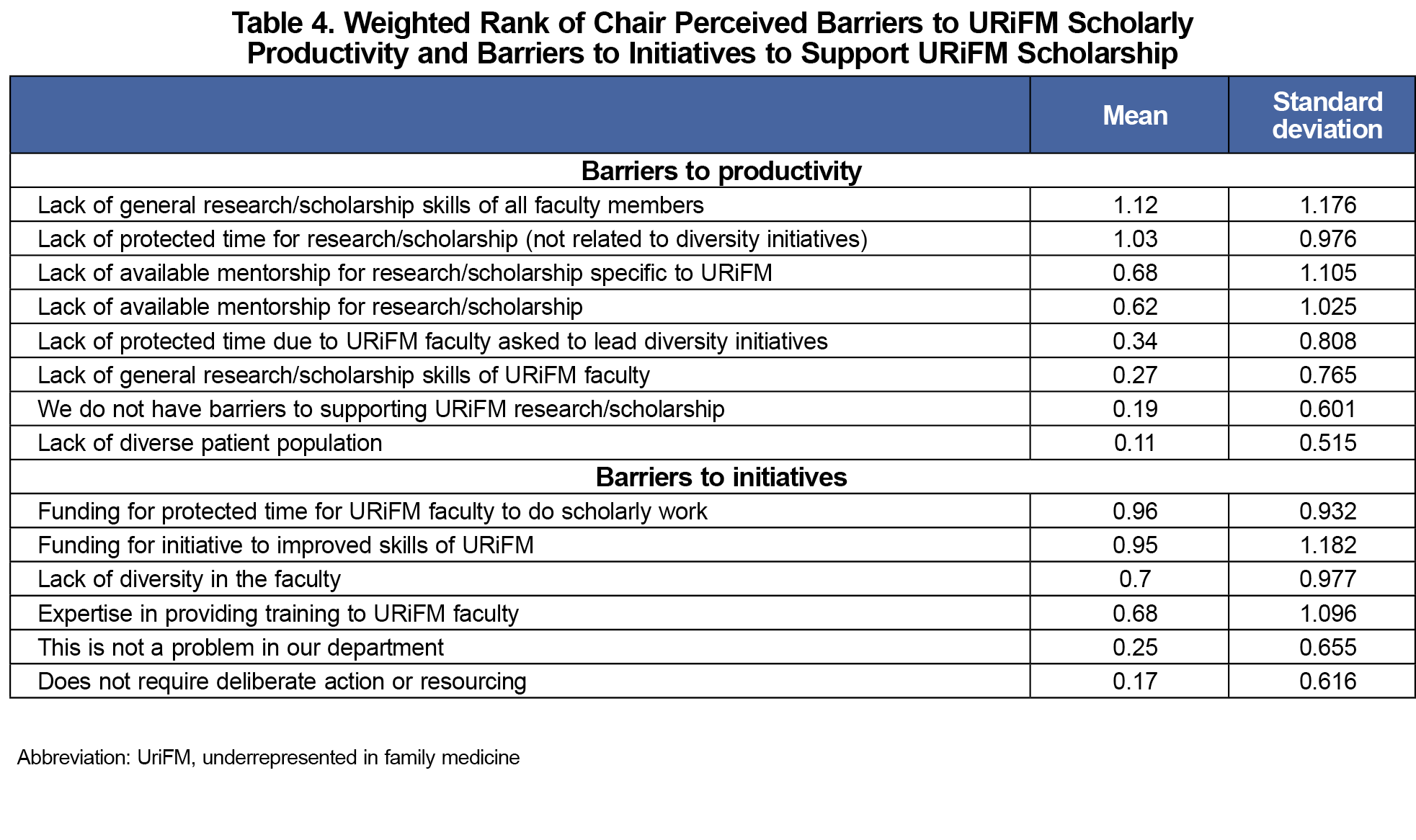

Among 225 eligible chairs, 109 chairs completed all 10 survey items (48.4%). Department, faculty, and chair characteristics and allyship scores are shown in Table 2. Fewer than one in ten departments reported a program dedicated to URiFM scholarship, and nearly half reported URiFM scholarly output as minimal or absent (Table 3). Lack of general research skills was the most common barrier to productivity and lack of funding for protected time for URiFM faculty was the most common barrier for program development, whereas the minority tax (lack of protected time due to URiFM faculty asked to lead diversity initiatives) was ranked fifth out of eight potential barriers (Table 4). Given that the minority tax analysis was exploratory, these descriptive findings should be interpreted with caution.

In adjusted models, no variables uniquely predicted chair identification of the minority tax as a barrier to scholarship, including allyship measures and no variables predicted chairs reporting a program to support URiFM scholarly productivity (Table 5).

Our findings suggest that URiFM faculty in family medicine remain scarce among family medicine chairs and faculty, and dedicated programs to support URiFM scholarship are rare. In addition, few departments offer programs to support URiFM scholarly advancement. Chair allyship scores, chair characteristics, and department FTE did not predict if a department had a program to support URiFM scholarly productivity. Our findings also suggest that most department chairs do not recognize the minority tax as a potential barrier to URiFM scholarship. Although our exploratory analysis of minority tax recognition was limited by the constraints of adapting a validated instrument for the CERA survey, this finding may warrant further investigation with more comprehensive measures.

This study did not find evidence that lower allyship was associated with inequitable distribution of resources for URiFM. Rather, the scholarly environment for family medicine appears to be underresourced in general, suggesting that allyship alone may be insufficient for URiFM individuals to overcome the structural barrier of departmental funding.13-15

Our study has limitations. Chairs reported their perceptions of percentage of URiFM faculty in their departments and their scholarly productivity. Both reports may be inaccurate. Levels of minimal, moderate, and extensive research/scholarly activity were not defined in survey questions which could also lead to inaccuracy. Although validated measures of allyship were used, respondent bias (eg, recall bias, social desirability) may exist; furthermore, only a subset of the items from the original scale were used, which could limit validity. Although the response rate to the survey was adequate, nonresponders might be significantly different from those who responded. Finally, although we had a North American sample of department chairs, only 109 chairs were included, limiting the power to detect smaller effects.

Based on the findings in our study, areas for future research include expanding the sample size to increase power, as larger data sets may reveal more subtle trends or differences. Asking URiFM faculty directly about their experiences and scholarly output could capture a broader range of perspectives and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the barriers URiFM faculty face. Focus groups of URiFM faculty with and without programs to support their scholarly productivity could be deployed to better understand their potential impact. The impact of federal changes around programs to support workforce diversity in academic medicine should also be explored.

The academic family medicine workforce is persistently less diverse than the populations that physicians serve. This study found most department chairs report low scholarly output for URiFM faculty and lack programs to support them. Allyship scores were not associated with department chair actions to promote URiFM scholarship, suggesting that barriers are more systemic.16 Addressing structural obstacles such as insufficient protected time, research funding, and inadequate mentorship is necessary to create a more equitable academic environment.

Acknowledgments

Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD, Kim Kardonsky, MD, and Kristen Bene, PhD worked on the original CERA survey submission but declined additional involvement in this manuscript.

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Family Medicine Facts: Table 3. AAFP. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.aafp.org/about/dive-into-family-medicine/family-medicine-facts/table3.html.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Faculty Roster: U.S. Medical School Faculty. AAMC. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/faculty-institutions/report/faculty-roster-us-medical-school-faculty.

- S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: United States. U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045224.

- Collazo A, Walcher CM, Campbell KM. Underrepresented in medicine (URiM) faculty development: trends in biomedical database publication. J Natl Med Assoc. 2024;116(2 Pt 1):165-169. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2024.01.005

- Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6. doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

- Ellis D. Bound together: allyship in the art of medicine. Ann Surg. 2021;274(2):e187-e188. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004888

- Bresier V, Silver JK, Fleming TK. Achieving equity in academic medicine: a call for allyship. Acad Med. 2023;98(9):975-976. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005281

- Liaw W, Eden A, Coffman M, Nagaraj M, Bazemore A. Factors associated with successful research departments: a qualitative analysis of family medicine research bright spots. Fam Med. 2019;51(2):87-102. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.652014

- Kalet A, Libby AM, Jagsi R, et al. Mentoring underrepresented minority physician-scientists to success. Acad Med. 2022;97(4):497-502. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004402

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- Williams M, Sharif N. Racial allyship: novel measurement and new insights. New Ideas Psychol. 2021;62:100865. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2021.100865

- Kaplan SE, Raj A, Carr PL, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Race/ethnicity and success in academic medicine: findings from a longitudinal multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):616-622. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001968

- Ogbeide S, George D, Sandoval A, Johnson-Esparza Y, Villacampa MM. Clinical efforts double disparity for nonphysician URiFM faculty: implications for academic family medicine. Fam Med. 2024;56(6):346-352. PMID:38805629 doi:10.22454/FamMed.2024.553188

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Syed ZA, Shakil A, Schneider FD. Trends in tenure status in academic family medicine, 1977–2017: implications for recruitment, retention, and the academic mission. Acad Med. 2020;95(2):241-247. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002890

- Nilsen K, Walling A, Kellerman R. Family medicine faculty 2010-2019: gaining numbers, losing ground. Fam Med. 2020;52(5):376-378. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.159367

- Braxton MM, Infante Linares JL, Tumin D, Campbell KM. Scholarly productivity of faculty in primary care roles related to tenure versus non-tenure tracks. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):174. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02085-6

There are no comments for this article.