Introduction: Competency-based medical education (CBME) provides a paradigm shift in graduate medical education focusing on predefined competencies rather than time. This approach emphasizes frequent assessment along with resident-driven learning plans to promote continuous growth. We assessed how implementation of CBME was perceived by residents, affected resident knowledge, and impacted assessment data.

Methods: This was a single-institution, observational study conducted from July 2024 to June 2025. The curricular change included using a direct observation evaluation form, creation of individualized learning plans, and training faculty to be coaches. Perception of CBME implementation was evaluated through a survey sent to all residents. Pre- and postexposure data were collected on in-training exam scores, milestone subcompetency scores, and total evaluations completed. We used descriptive statistics and a one-sided Welch’s t test for analysis.

Results: Resident survey data showed residents agreed that implementing CBME, direct observations evaluations, and coaching were positive changes. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education survey data showed an increase in satisfaction with faculty feedback from 3.7/5.0 to 4.0/5.0 postexposure. In-Training Examination scores increased after the exposure across all postgraduate years (P<.00005). The number of total evaluations increased from 646 pre-exposure to 1,173 postexposure. Milestone subcompetency scores did not increase postexposure.

Conclusion: Residents found implementation of CBME within a family medicine residency program to be generally positive. There was a dramatic increase in the number of evaluations completed and satisfaction with faculty feedback. Elements of CBME can be successfully implemented and improve evaluation processes used in family medicine residencies.

Graduate medical education emphasizes that residents must meet predefined competencies before graduation and board certification. The goal of competency-based medical education (CBME) is to evaluate these competencies in predefined outcomes rather than prespecified metrics. However, the process and the impact of evaluating competency needs to be better defined. Recent literature suggests that successful implementation of CBME involves an assessment system, timely evaluation, and monitoring progress during training.1-3 A narrative review of CBME methods found a lack of research on competency-based assessments methods and implored programs to evaluate resident perceptions of CBME.1

During the 2024-2025 academic year, The Ohio State University (OSU) Family Medicine Residency Program implemented CBME through on-demand assessments, structured individualized learning plans (ILPs), and faculty coaching of residents, based on recommendations from the Society of Teachers in Family Medicine (STFM) CMBE Task Force.4 Our study aims to assess residents’ perceptions of implemented components of CBME, determine if implementation of CBME resulted in increased competency and knowledge, and evaluate whether on-demand evaluations provided more comprehensive data on resident milestones.

Study Design

We conducted a single-institution educational program implementation evaluation from July 2024 to June 2025, utilizing both retrospective and prospective data. This study was conducted at OSU and received institutional review board approval (ID 20250296). The study was conducted while the residency participated in the STFM CBME pilot program.5

Participants

The study sample included 36 family medicine residents at OSU, including 27 active residents and nine residents who graduated in 2024. There were no exclusion criteria for this study. Retrospective data were collected for a year pre-exposure as a baseline. Residents in training during the study period were consented to complete a survey.

Description of Curricular Change

Elements of CBME were implemented in July 2024 including using a direct observation evaluation form created by STFM, requiring completion of quarterly individualized learning plans (ILPs) utilizing a template created by STFM , and having faculty serve as coaches.4-5 Faculty were encouraged to complete direct observation evaluations frequently, with the goal of each resident receiving one evaluation per week. Faculty also received training on how to serve as a coach and guide learners in developing ILPs.

Measurements

Resident perception of CBME was assessed via a one-time postexposure survey using questions with a Likert scale. Data were also collected from the 2024 and 2025 Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) surveys on “Satisfaction With Faculty Members Feedback.” We evaluated resident knowledge by collecting in-training exam (ITE) scores from 2023 and 2024. Additionally, all 19 milestones subcompetency scores were compared for each resident stratified by postgraduate year (PGY) from preexposure to postexposure. We assessed the impact of direct observation evaluations by evaluating the total number of evaluations from pre-exposure to postexposure. As the evaluations mapped to milestone subcompetencies, we also assessed how many milestone subcompetencies had data directly populated from the evaluations, comparing pre-exposure to postexposure.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics for survey data, number of evaluations completed, and number of milestone subcompetencies with data. Given unequal variances, we used a one-sided Welch’s t test to compare differences of ITE scores and milestone subcompetency scores.

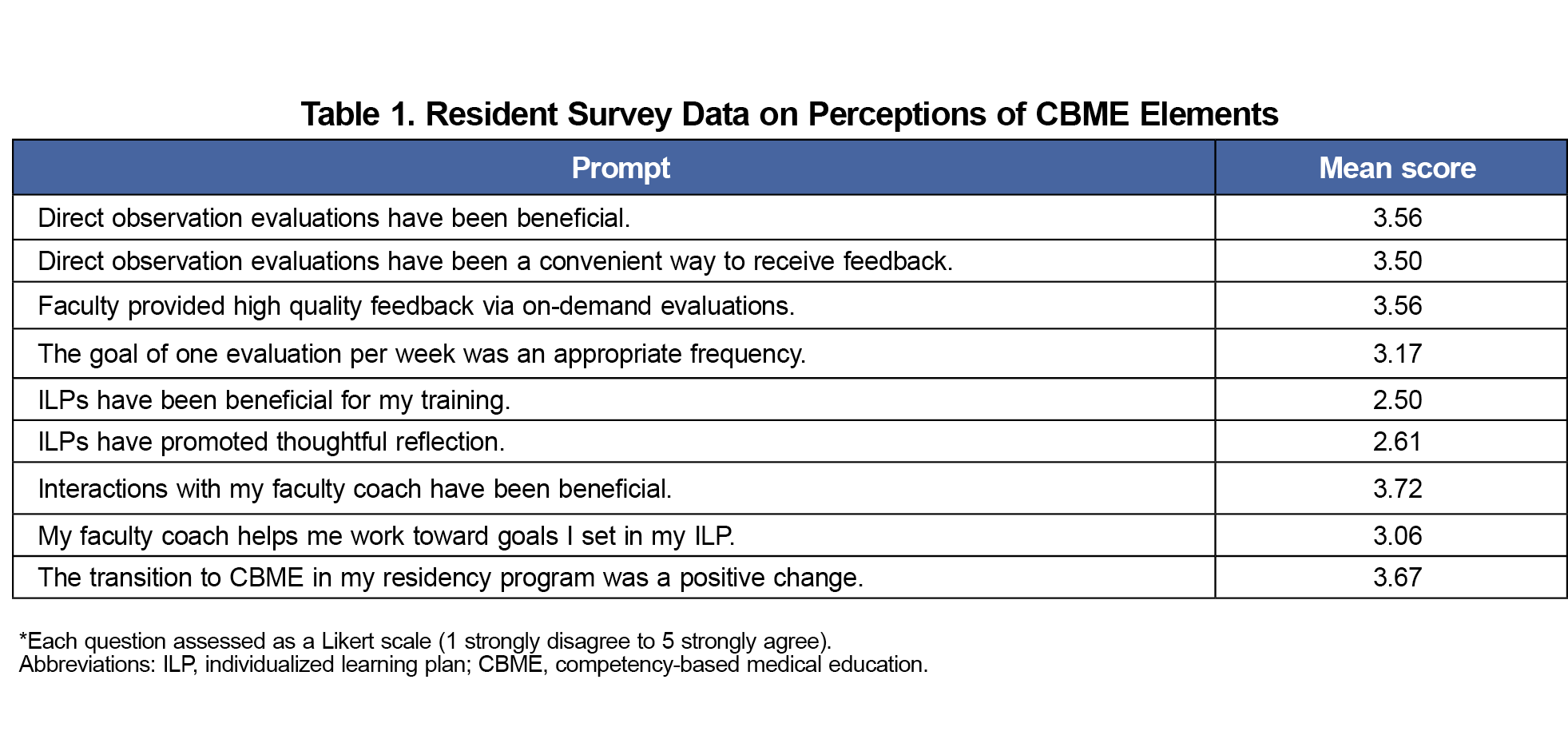

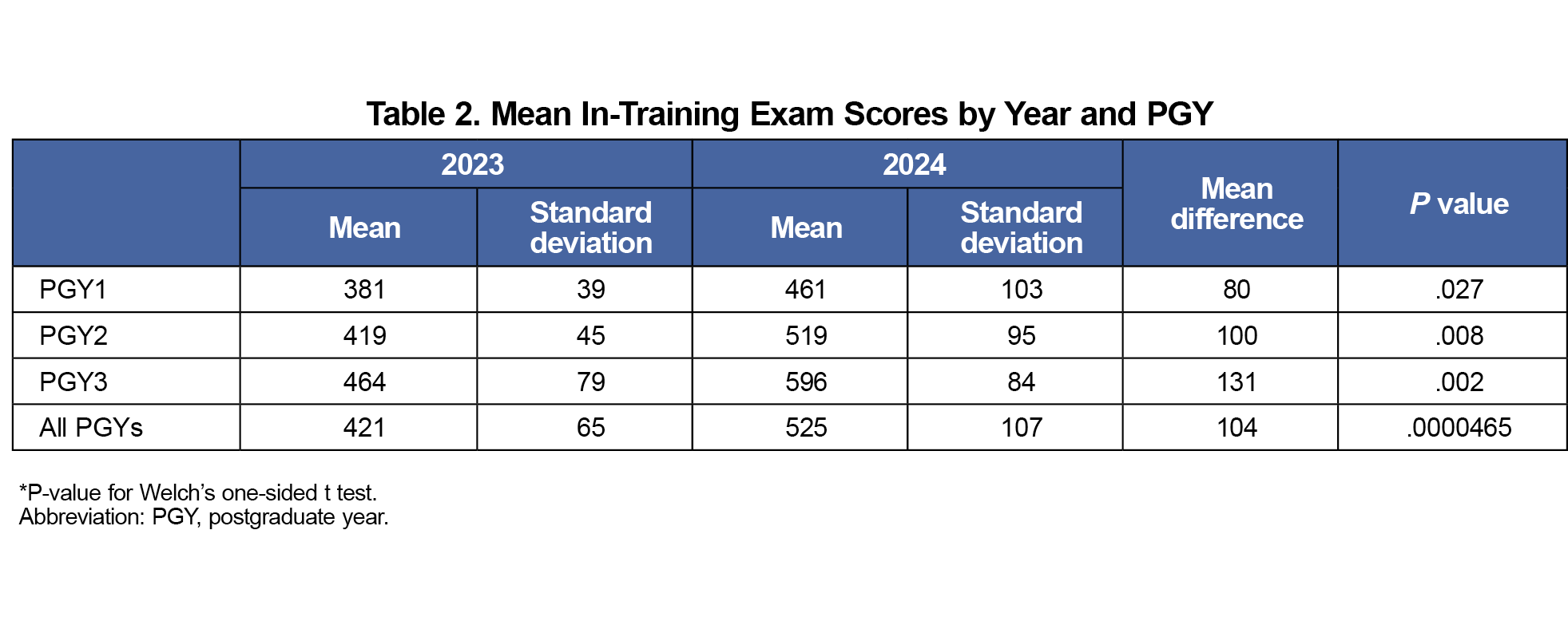

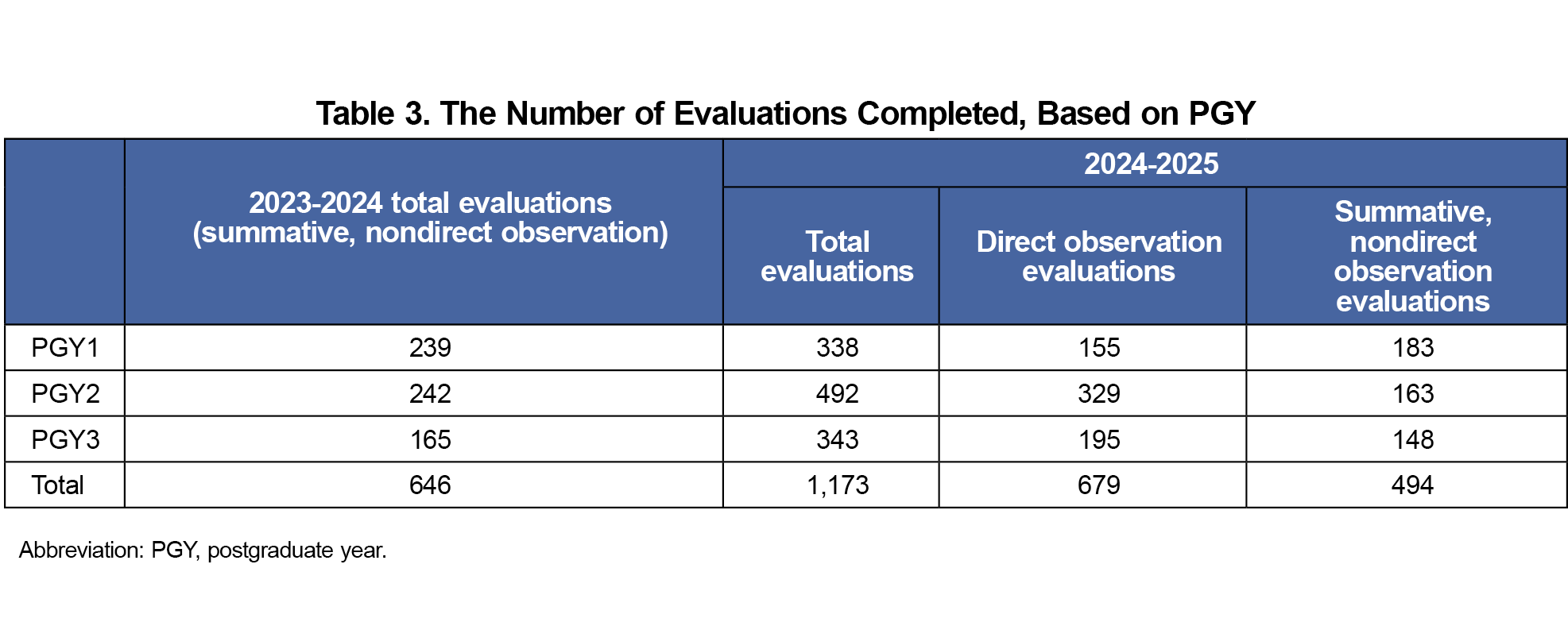

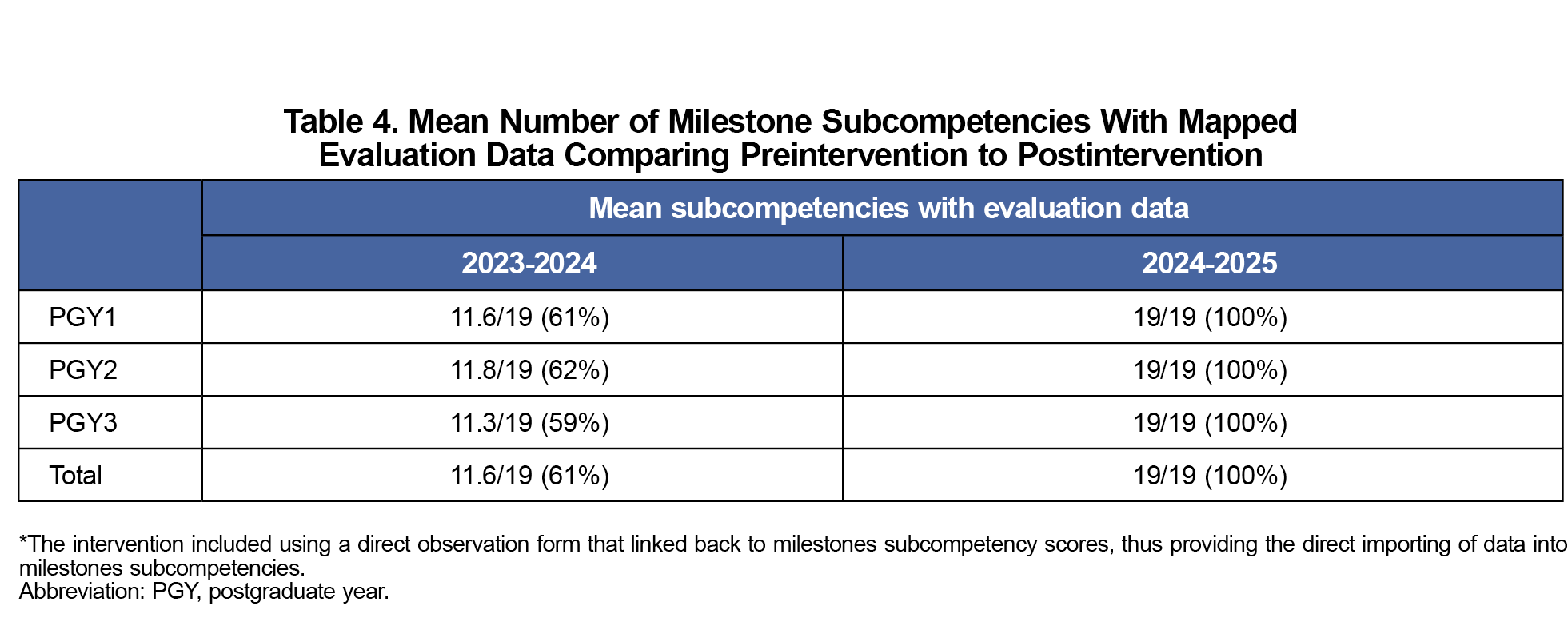

The resident survey was completed by 18 of the 27 eligible residents (Table 1). On average, residents agreed that implementing CBME was a positive change, and direct observations were beneficial. Residents were neutral on the benefits of ILPs. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education survey data showed an increase in satisfaction with faculty feedback from a 3.7/5.0 pre-exposure to 4.0/5.0 postexposure. ITE scores increased from a mean of 421(SD=65) pre-exposure to 525 (SD=170) postexposure across all PGYs (P<.00005) and for each individual PGY (Table 2). Except for statistically significant increases in SBP 1 and SBP 4 for PGY2s, no other milestone subcompetencies showed a significant change postexposure. The number of total evaluations increased from 646 to 1,173 postexposure, of which 679 evaluations were direct observation evaluations (Table 3). Out of the 19 milestone subcompetencies, a mean of 11.6 had linked data available pre-exposure, and all 19 had data available postexposure (Table 4).

Overall, residents viewed direct observations positively for evaluation of competency and resulted in an 82% increase in evaluations completed. Although implementing CBME did not directly improve milestone subcompetency scores, it did increase milestone data mapped from evaluations providing invaluable quantitative and qualitative data to the Curriculum Competency Committee. Faculty coaching was viewed positively, but the overall attitude toward performing ILPs was mixed.

Evaluating for competency rather than time-based requirements in medical education is an important shift for training residents transitioning from medical school to independently-practicing physicians.4 Survey data from program directors suggest many have graduated residents despite concerns.6-7 This highlights the importance in the shift toward competency-based, time-variable training in medical education, an approach that has been embraced in higher education in other fields for many years.8-9 This study highlights how elements of CBME can be used to gather high volumes of data, which can be used to identify gaps in competency and guide learning plans for learners to achieve competency. A study of implementing CBME at Canadian family medicine residencies also found an increase in evaluations, with an average of 150 evaluations per resident over 3 years.10 Increased assessment data helped these residencies identify red flags and competency trajectories sooner.10

It is important to note increased quantity of evaluations does not correlate with quality, as one study showed implementation of a CBME evaluation system led to variable assessment quality, distracted from learning, and was associated with resident anxiety.11

Limitations of this study include a small study sample and short duration of study. Although there was a large increase in the quantity of evaluations, most evaluations were completed by a few faculty, often at times when reminders were sent. Therefore, although exposure led to increased evaluations and coaching, the workload for faculty may not be sustainable. Future research and policy should focus on improved workflows and faculty protected time to allow for implementation of CBME. Although ITE scores improved with our exposure, the ITE was completed 3 months after implementation. Therefore, confounding factors such as class differences and didactic changes may better explain improvements in ITE scores.

The results of this 1-year project indicate a positive trajectory for implementation of CBME in that it leads to more frequent assessment and guidance for learners. Further investigation should occur to assess long-term impact of CBME on practice outcomes. Furthermore, validation studies should occur for current direct observation assessment forms, to ensure they capture appropriate stages towards competency.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Erin Frey for her help in coordinating the research and collecting data.

Conflict Disclosure: Hiten Patel has done consulting work for GE healthcare for the Point-of-care ultrasound division, primarily in helping with product design and understanding scope of point-of-care ultrasound in family medicine. The work is not relevant to this study.

References

- Danilovich N, Kitto S, Price DW, Campbell C, Hodgson A, Hendry P. Implementing competency-based medical education in family medicine: a narrative review of current trends in assessment. Fam Med. 2021;53(1):9-22. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.453158

- Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, Swing SR, Frank JR. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):676-682. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2010.500704

- Lockyer J, Carraccio C, Chan MK, et al; ICBME Collaborators. Core principles of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2017;39(6):609-616. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1315082

- Tulshian P, Montgomery L, McCrory K, et al. National recommendations for implementation of competency-based medical education in family medicine. Fam Med. 2025;57(4):253-260. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2025.866091

- Theobald M. New resources help programs transition to competency-based medical education (CBME). Ann Fam Med. 2024;22(4):363-364. doi:10.1370/afm.3154

- Schumacher DJ, Kinnear B, Poitevien P, Daulton R, Winn AS. Advancing, graduating, and attesting readiness of pediatrics residents with concerns. Pediatrics. 2025;155(6):e2025070594. doi:10.1542/peds.2025-070594

- Santen SA, Hemphill RR. Embracing our responsibility to ensure trainee competency. AEM Educ Train. 2023;7(2):e10863. Published 2023 Apr 1. doi:10.1002/aet2.10863

- Nodine T. How did we get here? A brief history of competency-based higher education in the United States. J Competency-Based Educ. 2016;1(1):5-11. doi:10.1002/cbe2.1004

- Goldhamer MEJ, Pusic MV, Nadel ES, Co JPT, Weinstein DF. Promotion in place: a model for competency-based, time-variable graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2024;99(5):518-523. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005652

- Schultz K, Griffiths J. Implementing competency-based medical education in a postgraduate family medicine residency training program: a stepwise approach, facilitating factors, and processes or steps that would have been helpful. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):685-689. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001066

- Day LB, Colbourne T, Ng A, et al. A qualitative study of Canadian resident experiences with Competency-Based Medical Education. Can Med Educ J. 2023;14(2):40-50. Published 2023 Apr 8. doi:10.36834/cmej.72765

There are no comments for this article.