Despite the critical role that procedural competence plays in patient outcomes, assessment of technical skills such as suturing remains highly variable.1,2 While assessments for medical knowledge have become largely objective and reproducible, the evaluation of technical skills continues to depend primarily on subjective faculty impressions.3,4 In an era where patient safety and clinical outcomes are increasingly tied to the precision of hands-on care, the lack of standardized, validated tools to assess suturing ability represents a serious gap in medical education.1,2,4

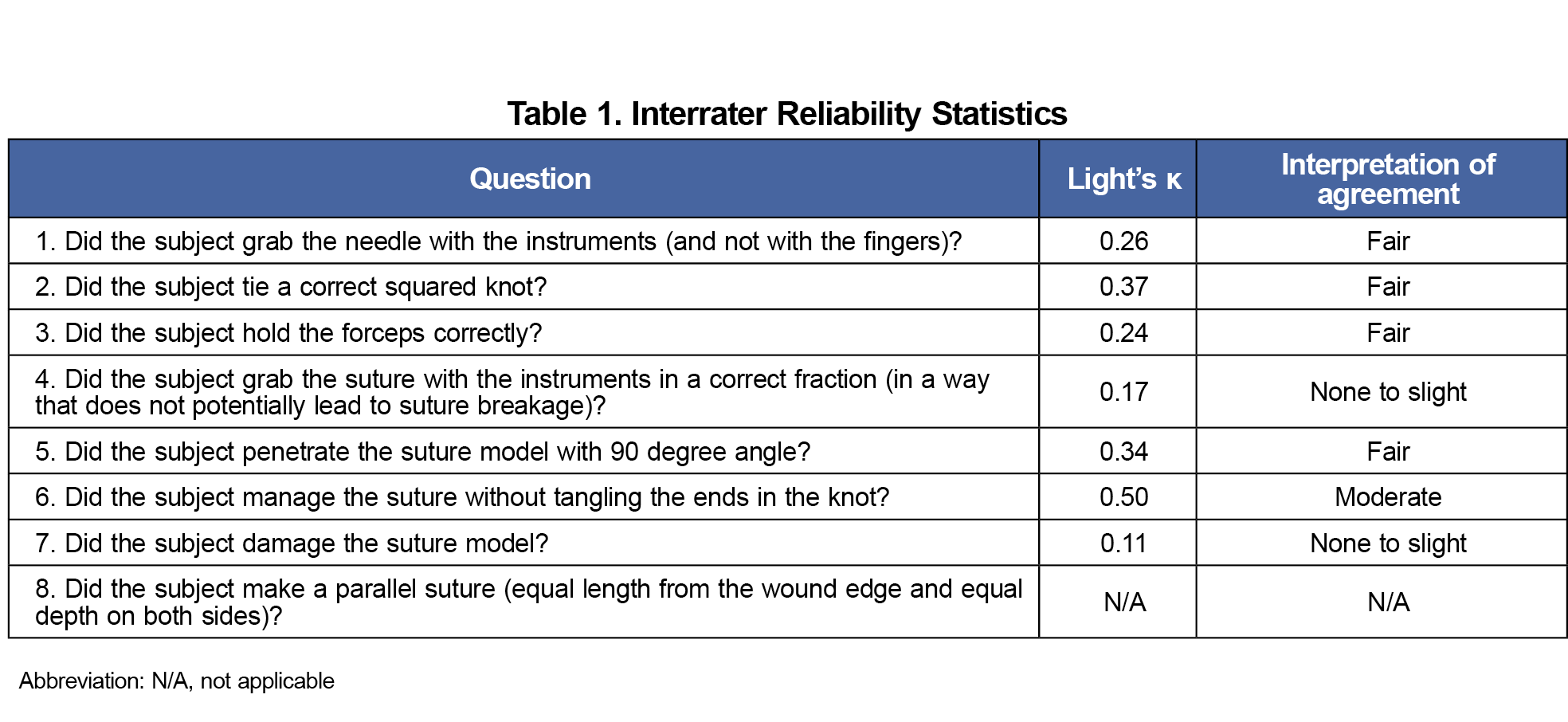

Family physicians frequently perform minor procedures, including suturing, as part of routine practice.5 Yet, procedural skill assessment in family medicine remains highly variable, often relying on informal faculty observation rather than structured, objective tools.6,7 While educators have developed tools aimed at standardizing surgical skill evaluation across surgical specialties, these tools have not been evaluated in family medicine contexts.2-12 For example, the objective structured assessment of technical skills (OSATS) is a performance-based examination aimed at assessing the clinical competence of surgical residents.2,8,10 However, its use remains limited by concerns over predictive validity and sparse application outside traditional surgical settings.3,4 To address these gaps, Sundhagen et al developed an assessment tool specifically for evaluating suturing skills in medical students. Their study demonstrated promising reliability and validity in medical student populations.2

Developing reliable approaches for evaluating suturing performance could enhance both feedback quality and resident skill development. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the interrater reliability of the Sundhagen suture assessment tool when applied to family medicine residents. By doing so, we aimed to determine whether the tool may serve as a feasible, objective framework for procedural skills assessment in family medicine residency training.

There are no comments for this article.