Today’s medical students have different priorities and expectations for work-life balance than previous generations.1,2 Stress and long work hours during residency training often lead to burnout, depression, suboptimal patient care, and an inferior educational experience.3-5 Studies of the few programs offering part-time options show that residents have less burnout, better faculty evaluations, and equivalent board pass rates compared to full-time colleagues.6 We hypothesized that the majority of medical students would desire flexible residency training schedules.

BRIEF REPORT

Medical Student Interest in Flexible Residency Training Options

Madison Piotrowski, BA | Debra Stulberg, MD | Mari Egan, MD, MHPE

Fam Med. 2018;50(5):339-344.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.169078

Background and Objectives: Medical residents continue to experience high rates of burnout during residency training even after implementation of the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty-hour restrictions. The purpose of this study is to determine medical student interest in flexible residency training options.

Methods: Researchers developed an 11-question survey for second through fourth-year medical students. The populations surveyed included medical students who were: (1) attending the 2015 American Academy of Family Physicians National Conference, the 2015 Family Medicine Midwest Conference, and (2) enrolled at University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago, Drexel University College of Medicine, and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

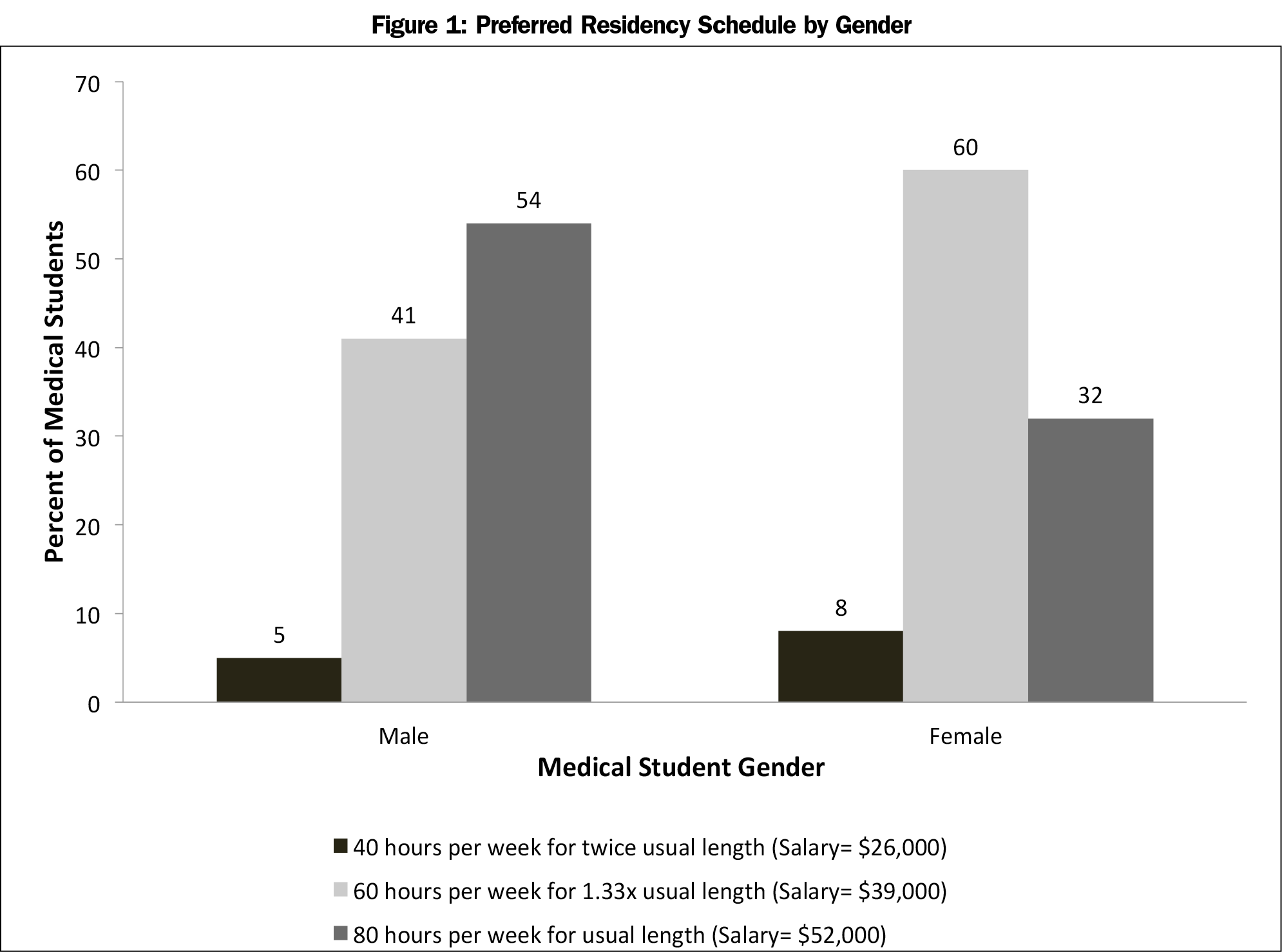

Results: The survey was completed by 789 medical students. Over half of medical students surveyed indicated that they would be interested in working part-time during some portion of their residency training (51%), and that access to part-time training options would increase their likelihood of applying to a particular residency program (52%). When given the option of three residency training schedules of varying lengths, 41% of male students and 60% of female students chose a 60-hour workweek, even when that meant extending the residency length by 33% and reducing their yearly salary to $39,000.

Conclusions: There is considerable interest among medical students in access to part-time residency training options and reduced-hour residency programs. This level of interest indicates that offering flexible training options could be an effective recruitment tool for residency programs and could improve students’ perception of their work-life balance during residency.

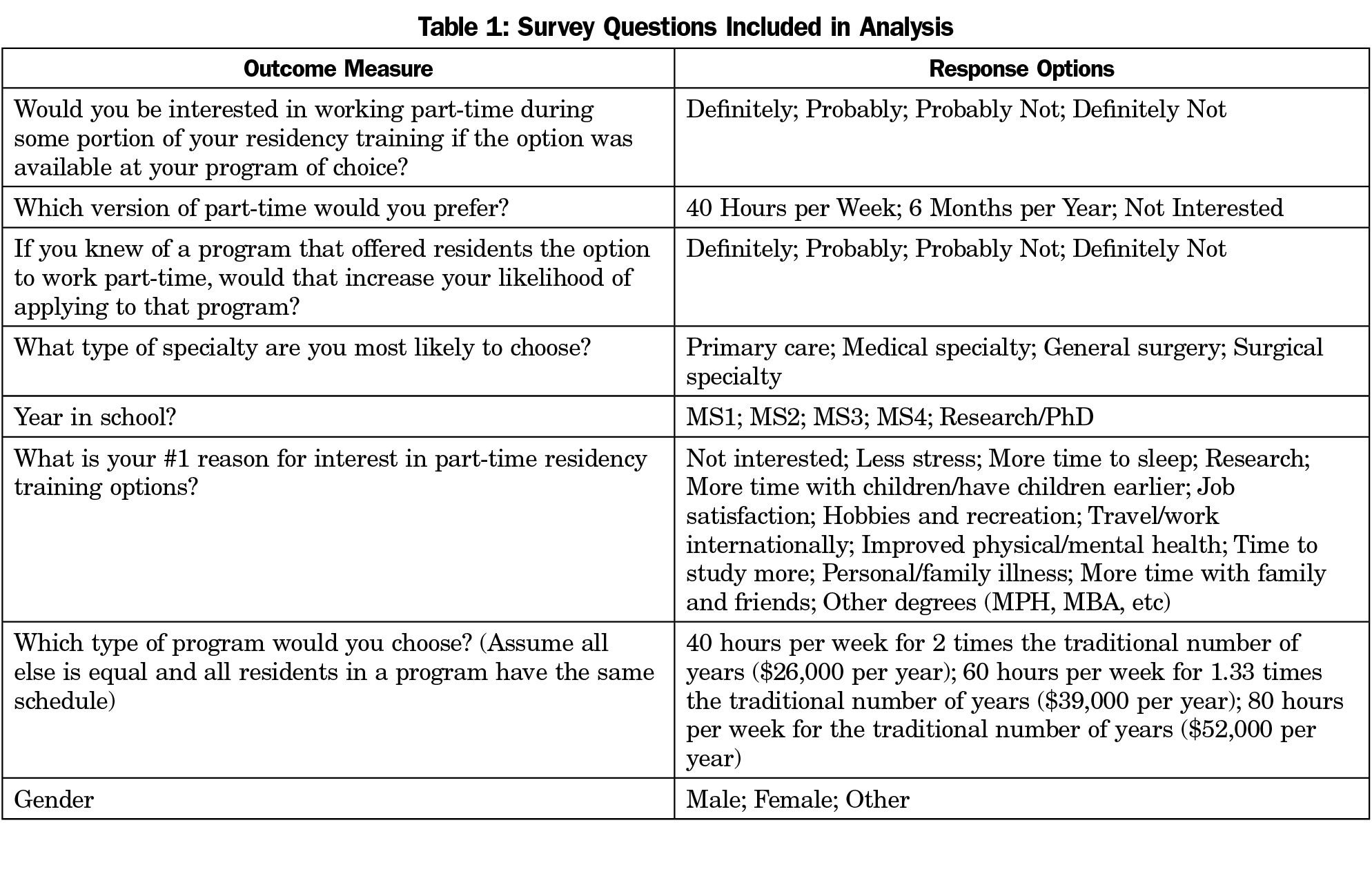

To assess medical students’ interest in flexible residency training options we developed an 11-item survey using a combination of expert opinion, literature review, and a pilot study at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. We designed one question based on an instrument utilized in a prior study with similar intent at the Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1976.7 The survey questions included in this analysis are listed in Table 1. This study received an exemption from the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. We surveyed second through fourth-year medical students at (1) the 2015 American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) National Conference of Family Medicine Residents and Medical Students, the 2015 Family Medicine Midwest Conference, and (2) the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago, Drexel University College of Medicine, and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

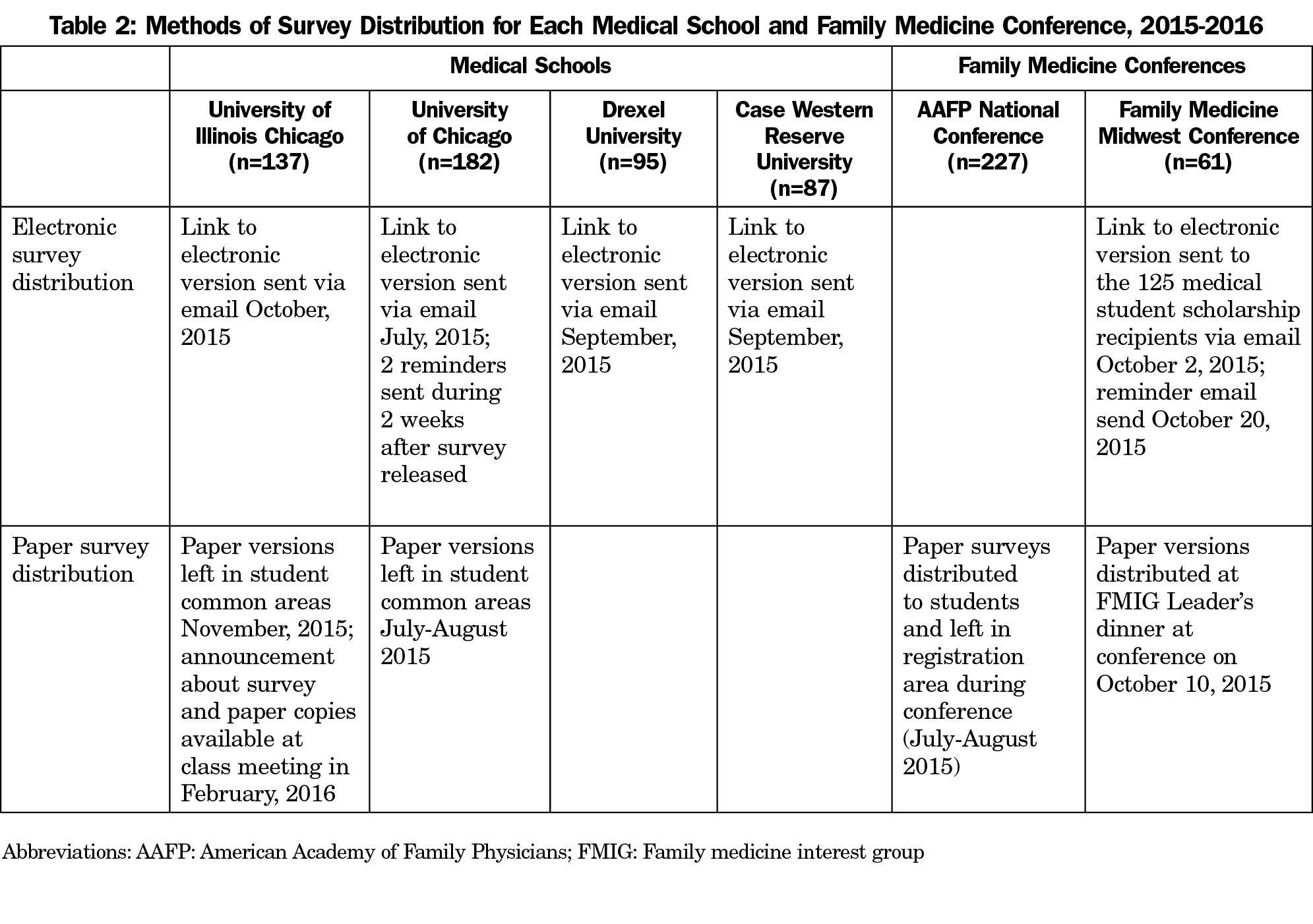

Data was collected between July 2015 and February 2016. Surveys were printed and an identical electronic version utilized SurveyMonkey. No incentives were offered for survey completion. Distribution methods are explained in Table 2. We analyzed data using Stata 14 (College Station, TX) and used two sample tests of proportions and chi-square tests to compare preference for flexible training by survey subgroup, gender, specialty choice, and medical school year.

Participants

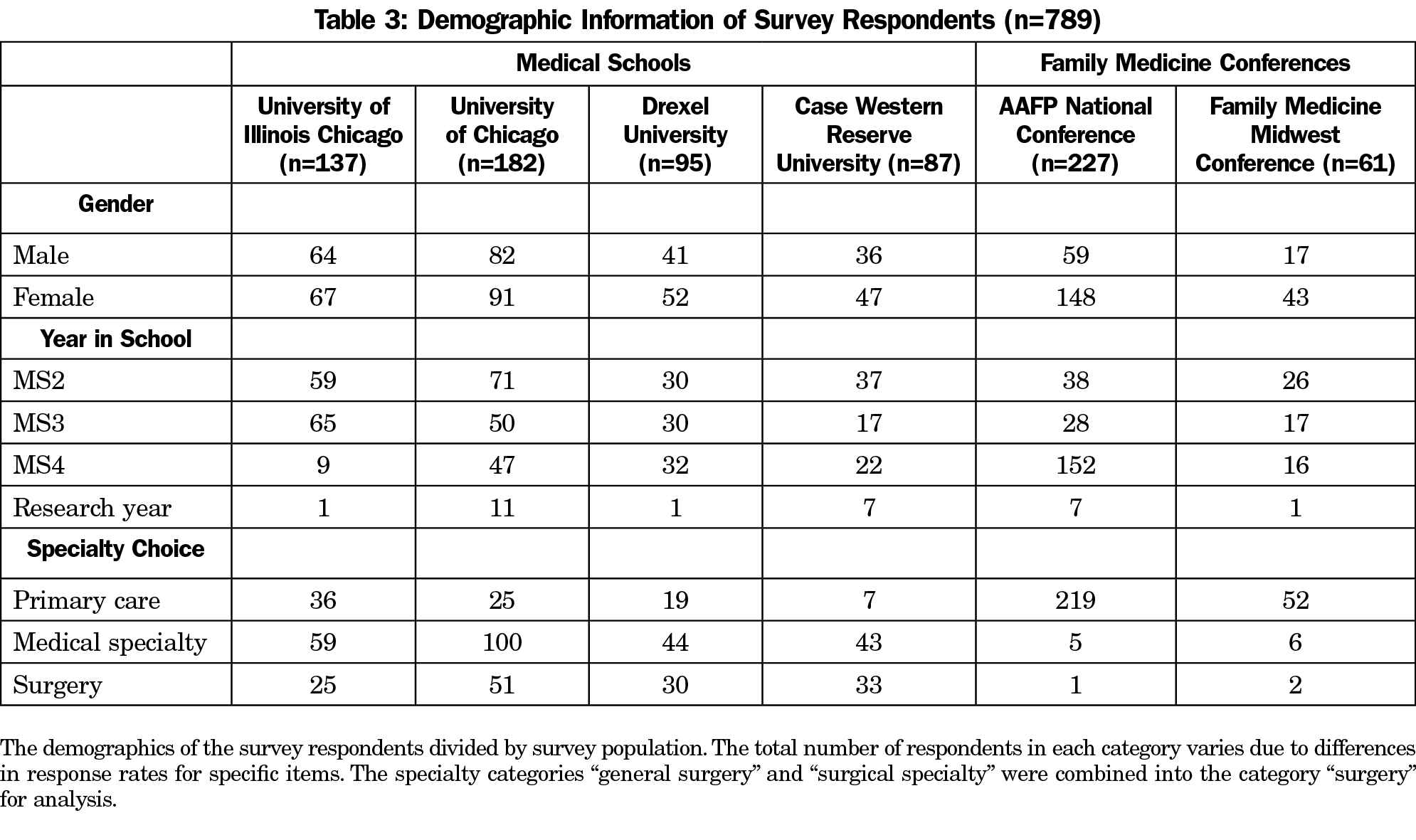

The survey was completed by 789 medical students; 227 students at the 2015 AAFP National Conference (19% response rate),8 61 students at the 2015 Family Medicine Midwest Conference (53% response rate), 182 students at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine (67% response rate), 137 students at University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago (13% response rate), 95 students at Drexel University College of Medicine (12% response rate), and 87 students at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine (14% response rate). There is a large difference between the response rates at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine and the other three medical schools surveyed, however we found no statistically significant difference between student responses regarding interest in part-time options (P=.188) or reduced-hour residency schedules (P=.389). Table 3 presents respondents’ demographic information.

Interest in Access to Part-time Training Options

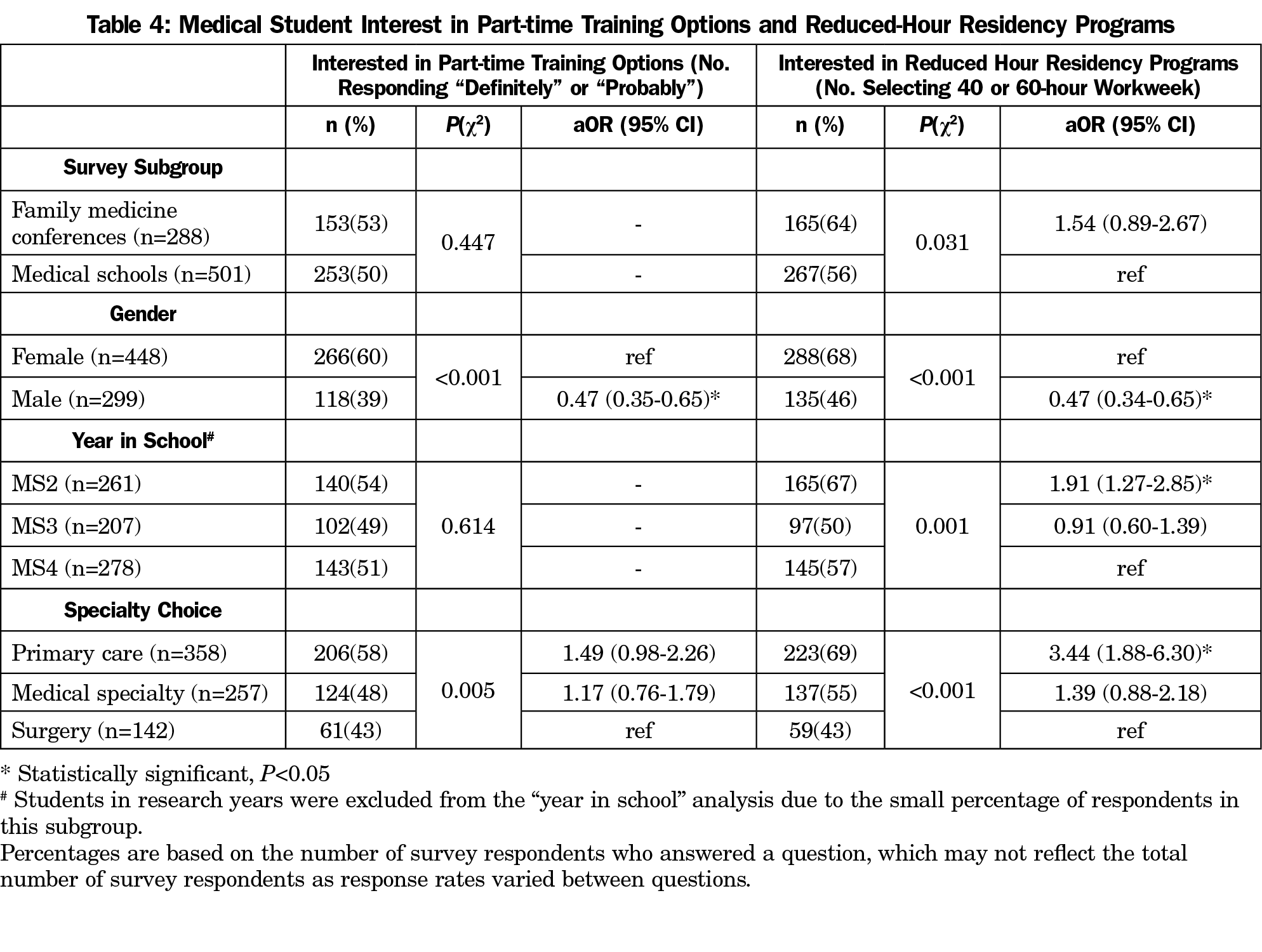

The majority of survey respondents (51%, n=406) said they were “definitely” or “probably” interested in working part-time during a portion of residency training. The most commonly cited reason for interest in part-time residency training options was “more time with children/ have children earlier.” When given the option of either working 40 hours per week or 6 months per year, 69% (n=423) of students who expressed interest in part-time options preferred the 40-hour workweek. Over half (52%; n=408) of students reported that they would be more likely to apply to a residency program that offered part-time training options. Interest in part-time training is significantly higher among women than men, even controlling for potential confounders (Table 4). In bivariate analysis, specialty choice was significantly associated with interest in part-time training options (primary care: 58%, medical specialty: 48%, surgery: 43%; P=.005), however controlling for gender, specialty choice was no longer significant.

Selection of Program Type

As an alternative to part-time options, we described three schedule variations and told students that all residents within the program would have the same schedule. Schedules were as follows:

- 40 hours per week for twice the residency length (salary=$26,000 per year)

- 60 hours per week for 1.33 times the residency length (salary= $39,000 per year)

- 80 hours per week for the traditional residency length (salary= $52,000 per year).

The 40 and 60-hour schedules will be referred to together as reduced-hour residency program schedules. Well over half of students (59%; n=432) selected a reduced-hour schedule; interest was significantly higher for women than men (68% vs 46%, P<.001; Figure 1) and varied by specialty choice (primary care: 69%, medical specialty: 55%, surgery: 43%; P=<.001; Table 4).

Even after the implementation of duty-hours restrictions, resident burnout continues to be a pervasive problem—in a 2014 study, 60% of residents met criteria for burnout.9 Our study examines medical student interest in flexible residency training options. Over half of students desired part-time training options and even more selected reduced-hour programs; the most popular schedule was a 60-hour workweek. Within a residency program, this would mean four reduced-schedule residents could fill three full-time-equivalent positions. However, although there are currently residency programs offering residents the option of working part-time for a portion of their residency training, we do not know of any training programs which have all reduced-time residents.10

We found that interest in flexible residency training options was higher among women and students interested in primary care. Female residents were more likely than male residents to choose part-time (60% vs 39%, P<.001) or reduced hour (68% vs 46%; P<.001) training options. We posit that this difference is likely at least in part related to the disparity in childcare responsibilities managed by female and male resident physicians. Recent studies have shown that over 40% of residents have children before or during their graduate medical education training,11-13 and resident fathers are twice as likely as resident mothers to have a partner who performs a greater percentage of childcare duties.12 As for students interested in primary care, we hypothesize that they were more willing to extend their residency to take advantage of flexible training options because their residency training is of a shorter duration.

In addition to improving resident work-life balance,14 flexible training options may reduce residency scheduling and coverage challenges, enhance medical student recruitment, and improve resident learning due to instruction occurring over more time.14,15 However, there are also several potential downsides to less than full-time training, notably the reduction in salary at a time when average medical student debt is over $189,000.16 Additionally, in a reduced-hour program, residents may not be able to revert to a full-time training schedule if they change their mind about their willingness to extend residency training and accept a reduced salary. If flexible training options were to become more common within residency programs, further studies would be necessary to evaluate the impact of these alternate schedules on continuity of care, quality of care, and professional relationships.14

Limitations

Our response rates at the AAFP National Conference and three of the four medical schools sampled were disappointingly low (12% to 19%), and our results, therefore, may have been affected by nonresponse bias. Additionally, the medical students responding to our survey represented a convenience sample, and conference attendees were a fundamentally different cohort of medical students than those from the four medical schools. The dissemination methods varied, as students at the AAFP National Conference did not have access to the electronic version of the survey, and students did not have access to paper versions of the survey at two of the four medical schools, which may have biased students sampled. First-year medical students were excluded from the survey population as the survey period began before the new academic year started. The survey did not specify which fields of medicine were considered primary care versus medical specialties, so this was left to students’ interpretation. A further limitation of this study is that after the implementation of the 80-hour workweek duty-hours restriction, residents work approximately 68 hours per week when averaged between specialties over the course of their training, so it is unclear in our reduced-hour residency program scenario how many hours per week residents would end up working on average for the 40 and 60-hour workweek options.17

Future Studies

It is unknown what effects flexible residency training options might have on the physician workforce. If part-time options or reduced-hour residency programs were to become more prevalent, future studies would be warranted to determine whether these training options would influence projected physician shortages. These alternatives to traditional residency training could theoretically influence future physician productivity based on their potential effects on demand for part-time work, retention within the workforce, timing of childbearing, and the timing and nature of partial-retirement for physicians ending their careers.

In conclusion, our survey found that there is a strong interest among medical students in access to flexible residency training options. Over half of students surveyed indicated that access to part-time training options would increase their likelihood of applying to a particular program. Nearly half (46%) of male students and over two-thirds (68%) of female students stated that they would choose a 40 or 60-hour workweek residency schedule rather than the current 80-hour workweek residency schedule despite the extension of residency length and reduction in annual salary. This high level of medical student interest indicates that offering flexible training options could be a strong recruitment tool for residency programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Irma Hasham Dahlquist, Dr Janice Benson, Dr Barrett Fromme, and Dr Jeanne Farnan for their guidance and feedback while designing the survey and drafting this paper. The authors would also like to thank the many medical students who completed the survey and especially Rachel Stones, Emily Graber, Ruth Whitfield, Ariana Melendez, Brian Park, and Emily Stott for their help in distributing the survey to their medical school classmates.

Presentations: Poster presented at Family Medicine Midwest, Indianapolis, October 8, 2016.

References

- Gander P, Briar C, Garden A, Purnell H, Woodward A. A gender-based analysis of work patterns, fatigue, and work/life balance among physicians in postgraduate training. Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1526-1536.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eabd06. - Pew Research Center. Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to Change. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/02/24/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change/. Published February 24, 2010. Accessed August 7, 2015.

- Hoekelman RA. Stress experienced during pediatric residency training. Its causes, consequences, recognition, and solutions. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143(2):177-180.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150140063021. - Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358-367.

https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. - Martini S, Arfken CL, Balon R. Comparison of burnout among medical residents before and after the implementation of work hours limits. Acad Psychiatry. 2006;30(4):352-355.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.30.4.352. - Holmes AV, Cull WL, Socolar RR. Part-time residency in pediatrics: description of current practice. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):32-37.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0127. - Burkett GL, Gabrielson IW. A study of the demand for part-time residency programs. J Med Educ. 1976;51(10):829-835.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. AAFP National Conference Exhibitor Information. http://www.aafp.org/events/national-conference/exhibitors.html. Accessed May 23, 2016.

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134. - University of California San Francisco. Training Program-Flexible Pathway. http://medicine.ucsf.edu/education/residency/program/flexpath.html. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- Blair JE, Mayer AP, Caubet SL, Norby SM, O’Connor MI, Hayes SN. Pregnancy and paternal leave during graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):972-978.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001006. - Holliday EB, Ahmed AA, Jagsi R, et al. Pregnancy and parenthood in radiation oncology, views and experiences survey: results of a blinded prospective trainee parenting and career development assessment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92(3):516-524.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.02.024. - Snyder RA, Tarpley MJ, Phillips SE, Terhune KP. The case for on-site child care in residency training and afterward. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):365-367.

https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-12-00294.1. - Kamei RK, Chen HC, Loeser H. Residency is not a race: our ten-year experience with a flexible schedule residency training option. Acad Med. 2004;79(5):447-452.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200405000-00015. - Gordon MB, Sectish TC, Elliott MN, et al. Pediatric residents’ perspectives on reducing work hours and lengthening residency: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):99-107.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3498. - Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC FIRST. Medical student education: debts, costs, and loan repayment fact card. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2016_Debt_Fact_Card.pdf. Published October 2016. Accessed January 31, 2017.

- Jagsi R, Weinstein DF, Shapiro J, Kitch BT, Dorer D, Weissman JS. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s limits on residents’ work hours and patient safety. A study of resident experiences and perceptions before and after hours reductions. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(5):493-500.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2007.129.

Lead Author

Madison Piotrowski, BA

Affiliations: Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Co-Authors

Debra Stulberg, MD - Department of Family Medicine, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Mari Egan, MD, MHPE - Pritzker School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, University of Chicago

Corresponding Author

Madison Piotrowski, BA

Correspondence: 5841 S Maryland Ave, MC 7110, Suite M-156, Chicago, IL 60637. 203-216-7773.

Email: mcrocker@uchicago.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.