Background and Objectives: Nonphysician faculty are common in academic family medicine departments and residencies. The objective of this study was to examine whether these nonphysician faculty have adopted a professional identity of family medicine and how that relates to job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Methods: In 2017, a survey of nonphysician members of the Council of Academic Family Medicine organizations in the United States and Canada was conducted. The overall response rate for the survey was 52.6% (526/1,001). The current analysis was conducted on the individuals who met all of the inclusion criteria and had complete data on all investigated scales (n=360). Scales on professional identity, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment were examined along with age, gender, race, and professional characteristics.

Results: The respondents indicated a professional identity with family medicine, commitment to their organization, and high job satisfaction. There was a lack of association with gender for these primary variables. Professional identity had a moderately positive relationship with years in family medicine (r=0.23). Professional identity had a moderately strong positive relationship with both commitment to the organization (r=0.41), and job satisfaction (r=0.43). In multivariate regressions, race/ethnicity was associated with both professional identity (P<.05) and job satisfaction (P<.05), with nonwhites having lower professional identity and job satisfaction.

Conclusions: The results of this survey of nonphysician faculty in family medicine indicated a high professional identity to family medicine, high job satisfaction, and commitment to their organization. Strategies including cultural competency training may serve as important tools to avoid dissatisfaction or turnover among this key workforce element in academic family medicine.

Identity is our reflective view of ourselves, including our social identity and our personal identity.1 Social identities are connected to our membership in groups.2 Family physicians typically perceive at least two levels of social identity; one as a physician, an identity they share with other physicians, and a second, more focused identity as a family physician.3

Within academic family medicine, faculties include not only family physicians but also other faculty, including nonphysician health care providers and nonphysician educators and researchers. According to the most recent numbers provided by the constituent organizations, a substantial portion of members of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) and the North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) are not physicians (Jessica Sand and Sarah Eggers, personal communication, 2017). Nonphysician faculty members are often integrated into the education and research activities of academic family medicine.4,5 Until recently, nonphysician faculty were restricted from taking on a role as a core member of residency programs per current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) policy.6 However, we do not know how nonphysician faculty perceive their social identity and role in academic medicine, and their internalization of a professional identity around family medicine is unclear.

One commentary raised the issue of potential conflicting role identities that nonphysician faculty may hold.7 Specifically, does the individual avow the identity of family medicine or does he or she avow the identity of a “home discipline,” such as that of a psychologist, anthropologist, epidemiologist, or pharmacist who is employed in a family medicine department? It can potentially be alienating to primary care physicians for a nonphysician colleague to stress that academic family medicine is not their academic home. Mutual respect for the intellectual contributions of each member of the team is necessary to build cohesiveness and buy-in by all participants.

While these conflicting issues are present, little research has been done to investigate how nonphysician faculty feel about their identity and integration into family medicine organizations. The aim of this study is to use a national survey of academic nonphysician faculty to investigate their feelings of identity in family medicine and the relation of that identity to job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

This study is an analysis of a regularly-conducted survey as part of the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA). CERA is a joint initiative of all four major US academic family medicine organizations (STFM, NAPCRG, Association of Departments of Family Medicine [ADFM], and Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors [AFMRD]). The CERA Steering Committee chose to include our study’s questions as part of the larger omnibus survey in their regular cyclical survey. This study’s questions were evaluated by the CERA Steering Committee for consistency with the overall subproject aim, readability, and existing evidence of reliability and validity. Pretesting was done on family medicine faculty who were not part of the target population. Questions were modified following pretesting for flow, timing, and readability. The project was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board in June 2017. Data were collected from July 5, 2017 to August 13, 2017.

The sampling frame for the survey was nonphysician members of the Council of Academic Family Medicine organizations in the United States and Canada. Participants were selected based on membership type, followed by a screen validating the users’ credentials provided in their profiles. Email invitations to participate were delivered with the survey utilizing the online program SurveyMonkey. The survey was introduced in an email that included a personalized greeting, a letter signed by the presidents of each of the four participating organizations urging participation, and a link to the survey. After the initial email invitation, five follow-up emails were sent to encourage nonrespondents to participate. There were initially 1,016 identified individuals. Of those, 15 emails were undeliverable either as bounced or opted out of SurveyMonkey surveys, resulting in a final pool of 1,001 delivered surveys. The overall response rate for the survey was 52.6% (526/1,001).

For this study, the following exclusion criteria were used to delineate the final data set of participants. The exclusions that were made included participants who held an MD, DO, or equivalent and indicated their primary work setting as other than “at a medical school” or “at a residency program.” In addition, participants with missing data points that did not identify them demographically or had fully incomplete items from all of the scales used were also excluded from the final data set. Overall, 360 individuals completed the survey criteria and met all inclusion criteria.

The survey questions for this study were developed following a review of the literature to identify key concepts and issues suggesting the need for additional knowledge.

Professional Identity (PI)

We used four relevant items from the professional identity scale by Adams8 (1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree) to assess professional identity: “I feel like I am a member of this profession,” “I feel I have strong ties with members of this profession,” “I find myself making excuses for belonging to this profession,” and “Being a member of this profession is important to me.” Some items were reverse scored, meaning a score of 1 equated a score of 5, 2 equated a score of 4, etc.

Job Satisfaction (JS)

To assess job satisfaction, we used a measure similar to the one used by Landon et al10 (Cronbach α=0.82) to assess career satisfaction of primary care physicians. The single item was measured on a 1-5 scale (1=very dissatisfied; 5=very satisfied), “Thinking very generally about your satisfaction with your overall career in family medicine, would you say that you are currently very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, very dissatisfied, or neither satisfied nor dissatisfied?”

Commitment to the Organization (CTO)

We used the three-item scale used by Courcy10 (Cronbach α=0.79) and based on Becker.12 The items (1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree) are “I will probably look actively for another job soon,” “I often think about resigning,” and “It would not take much to make me resign.” Some items were reverse scored, meaning a score of 1 equated a score of 5, 2 equated a score of 4, etc.

Demographics

CERA collected data on age, gender, race/ethnicity, primary professional specialty, credentials, and education. In addition, CERA collected data on the clinical practice/educational settings of the survey respondents, including: (1) a description of their family medicine unit (allopathic, osteopathic, or mixed), (2) how their time was spent in their roles (education/training, research, service, clinical practice, administration, or other, (3) hours dedicated to: residents, medical students, other professional students, faculty, and other, and (4) their attendance at NAPCRG, STFM, and ADFM research events over the past 3 years. CERA did not collect data on salary/salary satisfaction due to a limitation on the quantity of items allowable for the CERA omnibus survey.

Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics to characterize and summarize the respondent sample. All scales were scored resulting in calculating mean and standard deviation for each. Bivariate analysis included stratification of the scale mean scores using demographic variables and clinical practice/educational settings variables. Pearson’s correlations were computed among each of the scales along with years in family medicine. Bivariate analyses included one-way analysis of variance tests and t-tests. Multivariate regression analysis was computed in forced inclusion models. Significance was defined as P<0.05 level of confidence.

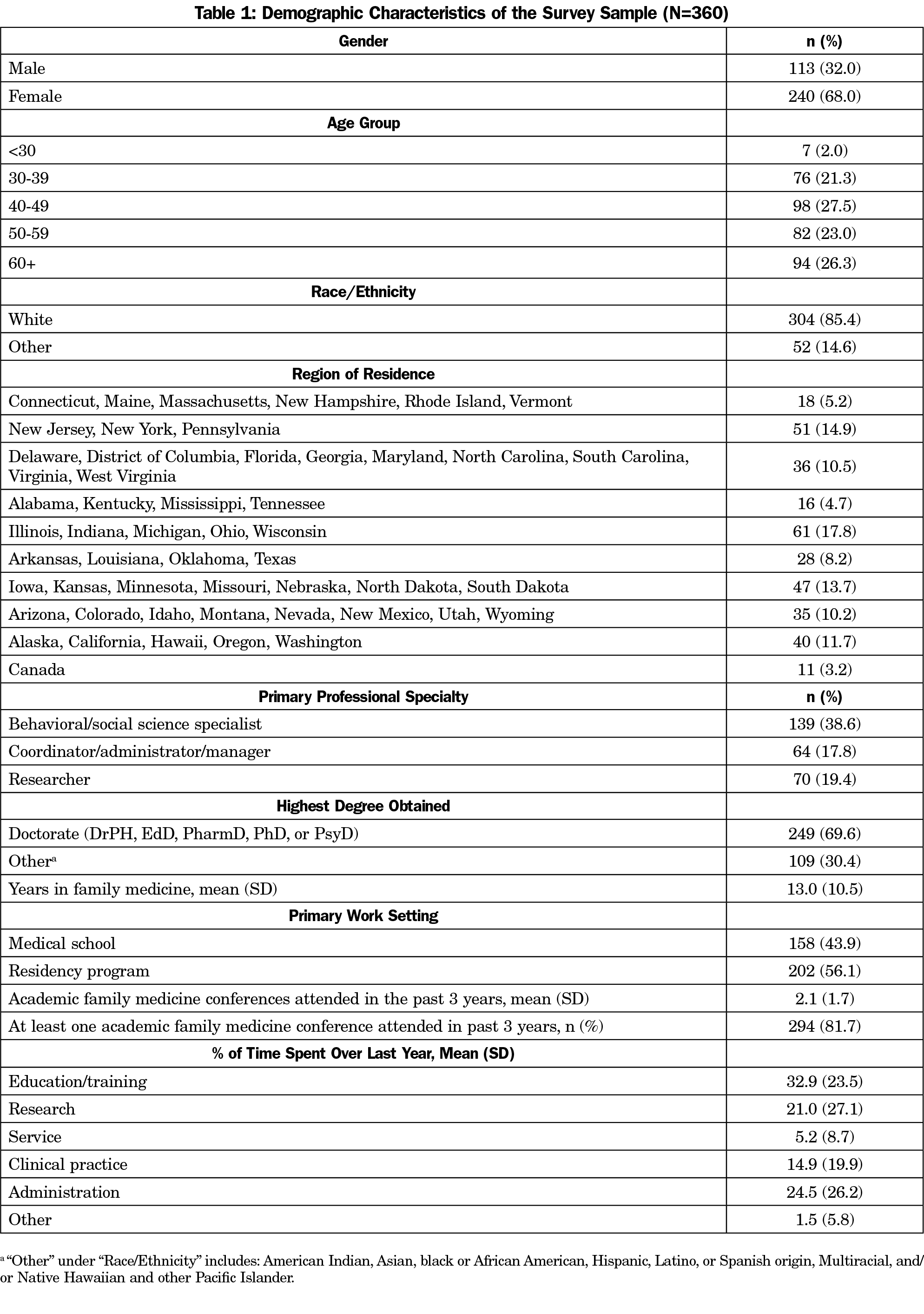

Table 1 indicates that the majority of respondents were white, female, and between the ages of 40 and 49 years old. A majority of respondents had a doctoral-level degree and spent an average of 21% of their time conducting research (SD=27.1). The respondents had worked in family medicine for a mean of 13 years (SD=10.5). They attended an average of 2.1 academic family medicine conferences (NAPCRG Annual Meeting, STFM Annual Spring Conference, ADFM Annual Meeting, STFM Conference on Practice Improvement, STFM Conference on Medical Student Education), in the past 3 years (SD=1.7).

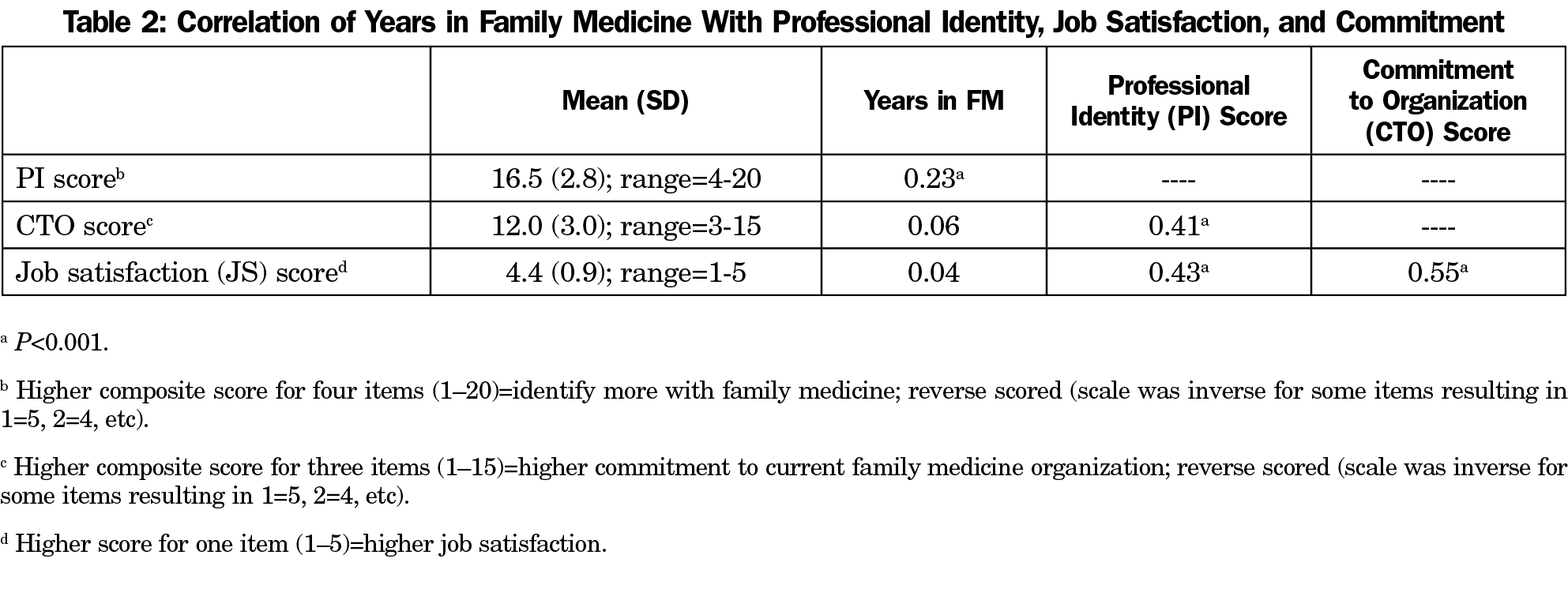

The respondents indicated a professional identity with family medicine, commitment to their organization, and high job satisfaction (Table 2). Professional identity had a moderately positive relationship with years in the family medicine setting. Professional identity had a moderately strong positive relationship with both commitment to the organization and job satisfaction.

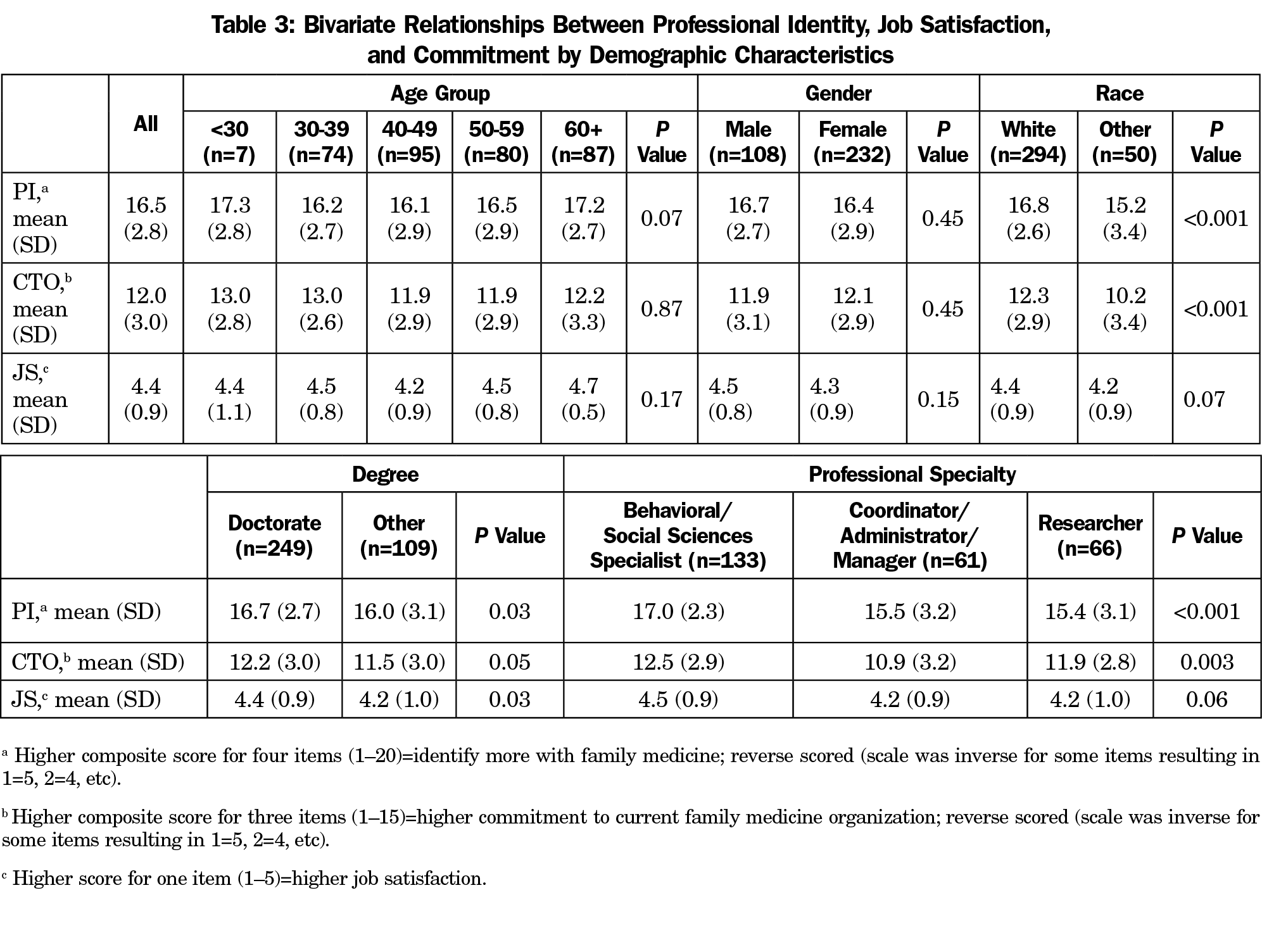

In bivariate analyses, neither age nor gender showed statistically significant differences with professional identity, job satisfaction, or commitment to the organization (Table 3). Professional identity and job satisfaction were statistically higher among those who identified as white versus those who identified as other. Those who indicated “Behavioral/Social Sciences Specialist” as their professional specialty held the highest mean scores for all scales with statistically significant differences present in respondents’ professional identity, and commitment to their organization. There was no statistically significant relationship between race/ethnicity and being a behavioral/social scientist versus coordinator/administrator/researcher (P=0.88).

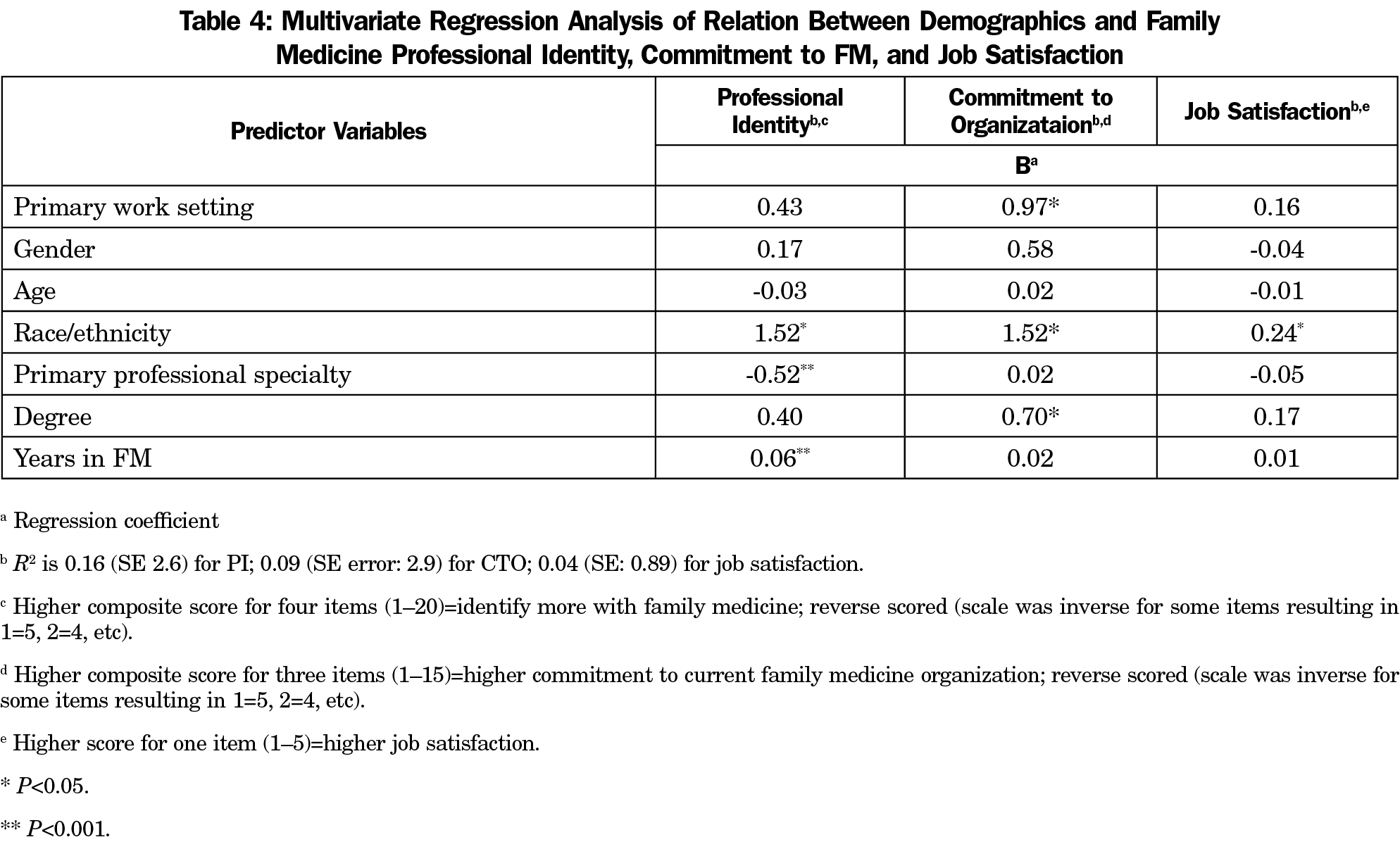

Multivariate regression analysis indicated that participants had lower ratings for sense of professional identity with family medicine (FM), job satisfaction, and commitment to the organization based on their race/ethnicity (Table 4). Their sense of professional identity with FM was positively related to their primary professional specialty and years in FM. Participants’ commitment to their organizations was also positively related to their primary work setting and degree.

The results of this survey of nonphysician faculty in family medicine indicated a high degree of professional identity with family medicine, high job satisfaction, and commitment to their organization. Most respondents held the highest level of education in their field. Stratification by age or gender did not indicate differences in the professional identity of respondents with family medicine.

The high level of identity with family medicine, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment that nonphysician faculty have suggests that currently practiced approaches to integrating these faculty with the physician faculty are working. The result of this study fits the currently expected practice in academic family medicine, which is a setting occupied by medical educators and researchers from varying professional specialties working toward the common family medicine mission. Although respondents may continue to identify with the professional specialty of their education, they are still displaying high job satisfaction and professional identity with family medicine.

The results of this study show that one’s sense of professional identity with FM, job satisfaction, and commitment to the organization were related to race/ethnicity. The underlying causes of the racial differences in professional identity and commitment to the organization require further study. Addressing these and other variables will be important in order to maintain a racially diverse nonphysician faculty involved in family medicine departments and residency programs.

Higher scores for professional identity, and commitment to the organization were found in behavioral/social sciences specialists as compared to coordinators, administrators, managers, and researchers. This finding may be impacted by the current culture of family medicine that values care of patients that involve a behavioral medicine component. Conversely, family medicine faculty and residents may place less value on research as part of their training and career, and this implicit bias may affect these variables in the researcher group. Regardless, job satisfaction was similar in the professional specialties studied and higher in the respondents with a doctorate degree, suggesting this variable is more dependent upon level of training than environment of the department or program.

The method used in this study did not allow us to determine causality in these conceptual relationships; however, the results replicate previous research that professional identity is linked to organizational commitment.13-22 When we facilitate professional identity formation, we may be increasing organizational commitment and thereby reducing employee turnover. Separately but similarly, professional identity is linked to job satisfaction.8,13,20, 23-28 Additionally, we did not collect data on salary/salary satisfaction as a potentially important factor with a potentially unmeasured effect on the primary variables.

There are a few study limitations that should be considered. Due to the mode of sampling used in this study, nonresponse bias could be present due to CERA survey recipients who were unwilling or unable to participate. Though this may be the case, we do not expect this to alter our findings because of the topic and nature of the survey questions, as well as obtaining an adequate response rate. Second, respondents to these questions on the CERA survey could be more satisfied or identify more within the professional field of family medicine resulting in voluntary response bias. Third, racial categories were not split out from ethnic categories by CERA so the comparison of racial groups was completed as “white” versus “other,” creating a clustering of differing racial and ethnic groups for analysis.

In conclusion, factors such as years in family medicine, commitment to the organization, and job satisfaction are associated with professional identification with family medicine. Programs that involve cultural competency training and encourage further cross-cultural collaboration, both racially/ethnically and regarding professional specialty, may serve as important tools to avoid potential pitfalls resulting in nonphysician dissatisfaction or turnover.29 Additional studies are needed to determine the underlying factors associated with these findings. Further, future research may help to better understand issues surrounding race/ethnicity and attachment to the organization in academic family medicine.

Acknowledgments

The CERA survey was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians, June 2017 (#17-295).

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the Department of Defense at large.

References

- Ting-Toomey S. Identity Negotiation Theory: Crossing Cultural Boundaries. In: Gudykunst WB, ed. Theorizing about intercultural communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2005.

- Stryker S. Identity theory: developments and extensions. In: Yardley K, Honess T, eds. Self and Society: Psychosocial Perspectives. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1987.

- Carney PA, Waller E, Eiff MP, et al. Measuring family physician identity: the development of a new instrument. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):708-718.

- Harris DL, Krause KC, Parish DC, Smith MU. Academic competencies for medical faculty. Fam Med. 2007;39(5):343-350.

- Saultz J. Interdisciplinary family medicine. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):739-740.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. 13 November 2017. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ReviewandComment/120-17-FamilyMedicine-2017-11-13-R&C.doc.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2018.

- Wilson S, Mainous AG III, O’Donnell C, Bateman H. The integral role of non-clinical academics in meeting the goals of primary care training and research. Fam Pract. 2005;22(4):355-357. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmi017

- Adams K, Hean S, Sturgis P, Clark JM. Investigating the factors influencing professional identity of first-year health and social care students. Learn Health Soc Care. 2006;5(2):55-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2006.00119.x

- Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Blumenthal D. Changes in career satisfaction among primary care and specialist physicians, 1997-2001. JAMA. 2003;289(4):442-449. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.4.442

- Courcy F, Morin AJS, Madore I. The effects of exposure to psychological violence in the workplace on commitment and turnover intentions: the moderating role of social support and role stressors. J Interpers Violence. 2016;886260516674201; Epub ahead of print.

- Becker TE, Billings RS. Profiles of commitment: an empirical test. J Organ Behav. 1993;14(2):177-190. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030140207

- Wilson ME, Liddell DL, Hirschy AS, Pasquesi K. Professional identity, career commitment, and career entrenchment of midlevel student affairs professionals. J Coll Student Dev. 2016;57(5):557-572. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2016.0059

- Canrinus ET, Helms-Lorenz M, Beijaard D, Buitink J, Hofman A. Self-efficacy, job satisfaction, motivation and commitment: exploring the relationships between indicators of teachers’ professional identity. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2012;27(1):115-132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0069-2

- Marique G, Stinglhamber F. Identification to proximal targets and affective organizational commitment. J Pers Psychol. 2011;10(3):107-117. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000040

- De Vliegher K, Milisen K, Wouters R, et al; Belimage Homecare Group. The professional self-image of registered home nurses in Flanders (Belgium): a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(1):29-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2009.02.001

- Jourdain G, Chênevert D. Job demands-resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(6):709-722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.007

- Seruya FM, Hinojosa J. Professional and organizational commitment in paediatric occupational therapists: the influence of practice setting. Occup Ther Int. 2010;17(3):125-134. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.293

- Klein HJ, Brinsfield CT, Molloy JC. Understanding Workplace Commitments Independent of Antecedents, Foci, Rationales, and Consequences. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Atlanta. 2006.

- Myer JP, Becker TE, Vandenberghe C. Employee commitment and motivation: a conceptual analysis and integrative model. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(6):991-1007. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.991

- Gregg MF, Magilvy JK. Professional identity of Japanese nurses: bonding into nursing. Nurs Health Sci. 2001;3(1):47-55. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00070.x

- Gaziel HH. Sabbatical leave, job burnout and turnover intentions among teachers. Int J Lifelong Educ. 1995;14(4):331-338. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260137950140406

- Moore M, Hofman JE. Professional identity in institutions of higher learning in Israel. High Educ. 1988;17(1):69-79. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00130900

- Johnson M, Cowin LS, Wilson I, Young H. Professional identity and nursing: contemporary theoretical developments and future research challenges. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(4):562-569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.01013.x

- Deppoliti D. Exploring how new registered nurses construct professional identity in hospital settings. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2008;39(6):255-262. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20080601-03

- Horton K, Tschudin V, Forget A. The value of nursing: a literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(6):716-740. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733007082112

- Branch S. Who will I be when I leave university—the development of professional identity, November 2002. http://www.tedi.uq.edu.au. Accessed October 26, 2017.

- Adams A, Bond S. Hospital nurses’ job satisfaction, individual and organizational characteristics. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(3):536-543. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01513.x

- Lightstone E. Professional self-concept of medical-surgical hospital nurses: A conceptual analysis (Master dissertation). Toronto, ON, Canada; Graduate Department of Nursing Science University of Toronto, 1996.

- Pollart SM, Novielli KD, Brubaker L, et al. Time well spent: the association between time and effort allocation and intent to leave among clinical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):365-371. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000458

There are no comments for this article.