Background and Objectives: The program director (PD) position is challenging. PDs are faced with many competing priorities and risk of burnout. Short PD tenure may contribute to training program challenges. The tenure of family medicine residency directors has not been rigorously studied. Our objective was to study family medicine program director tenure and change in tenure over time, and compare these to available Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) data.

Methods: We analyzed the 11 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance PD surveys from 2011 through 2017. We calculated mean and median responses to the question “How long have you been program director at your current program?” We compared these results to data from the ACGME Data Resource Book for all specialty programs.

Results: Of 2,577 responses in 11 PD surveys over 7 years, mean family medicine PD tenure was 6.5 years and median tenure was 4.5 years. Tenure did not change significantly from 2011-2017, and 30.5% of PDs have been in their position 0, 1, or 2 years. The right skew in our data (ie, median substantially less than mean), is similar to that seen in other specialties.

Conclusions: Mean family medicine PD tenure is 6.5 years and median tenure is 4.5 years. The short tenure and large number of new PDs annually may impact program quality and suggests more resources and support may be needed for PDs new in their position.

The program director (PD) position is challenging. As one author notes, “We need to be honest. The job is tough. Not everyone can do it. Fewer still, it seems, are willing to do it for very long.”1 A PD mentors, teaches, leads faculty, cares for patients, develops curriculum, assesses leaners, produces scholarly output, all while managing graduate board certification requirements and increasingly complex accreditation mandates. PDs cite administrative duties, clinical load, family obligations, teaching responsibilities, and research demands as among their greatest stressors.2 One of the most common Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) citations is related to PD responsibilities.3 “It all starts and ends with the PD.”3

It is not known which skills or experience help a PD maintain an excellent residency program. PD participation in a leadership and management skills fellowship may improve program quality.4 Surveys show many PDs plan to step down in the next 1 to 2 years5,6 and burnout may be a factor.6,7 Between 11% and 14% of residency programs across specialties have at least one PD change annually.8 Some hypothesize that short average tenure of a PD may limit the strength of residency programs.5,9 While published articles have commented on PD tenure,1,2,5 and noted the “short life span,”2 PD tenure has not been rigorously studied and no study has tracked change in tenure over time.

The objective of our study was to describe the current tenure of family medicine residency directors, assess change from 2011 through 2017, and compare our results to nationally available data in family medicine and other specialties.

We analyzed data from 11 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) PD surveys from 2011-2017.10 CERA has developed the structure and expertise to administer an omnibus survey to key educators in family medicine.11,12 Data from the CERA omnibus surveys are freely available to members of Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) organizations. The Institutional Review Board of the American Academy of Family Physicians approved this CERA study.

Each of the 11 CERA PD surveys from 2011-2017 asked the question “How long have you been program director at your current program?” We calculated mean and median duration of service and analyzed differences over time using a Kruskal-Wallis test. This is a nonparametric test, as is used when data are not normally distributed.

We also visually compared data from the CERA survey to data from the publicly available ACGME Data Resource Book,8 which tracks PD tenure for departing PDs in all specialties. No statistical analysis could be performed to compare these, as only mean and median values are reported.

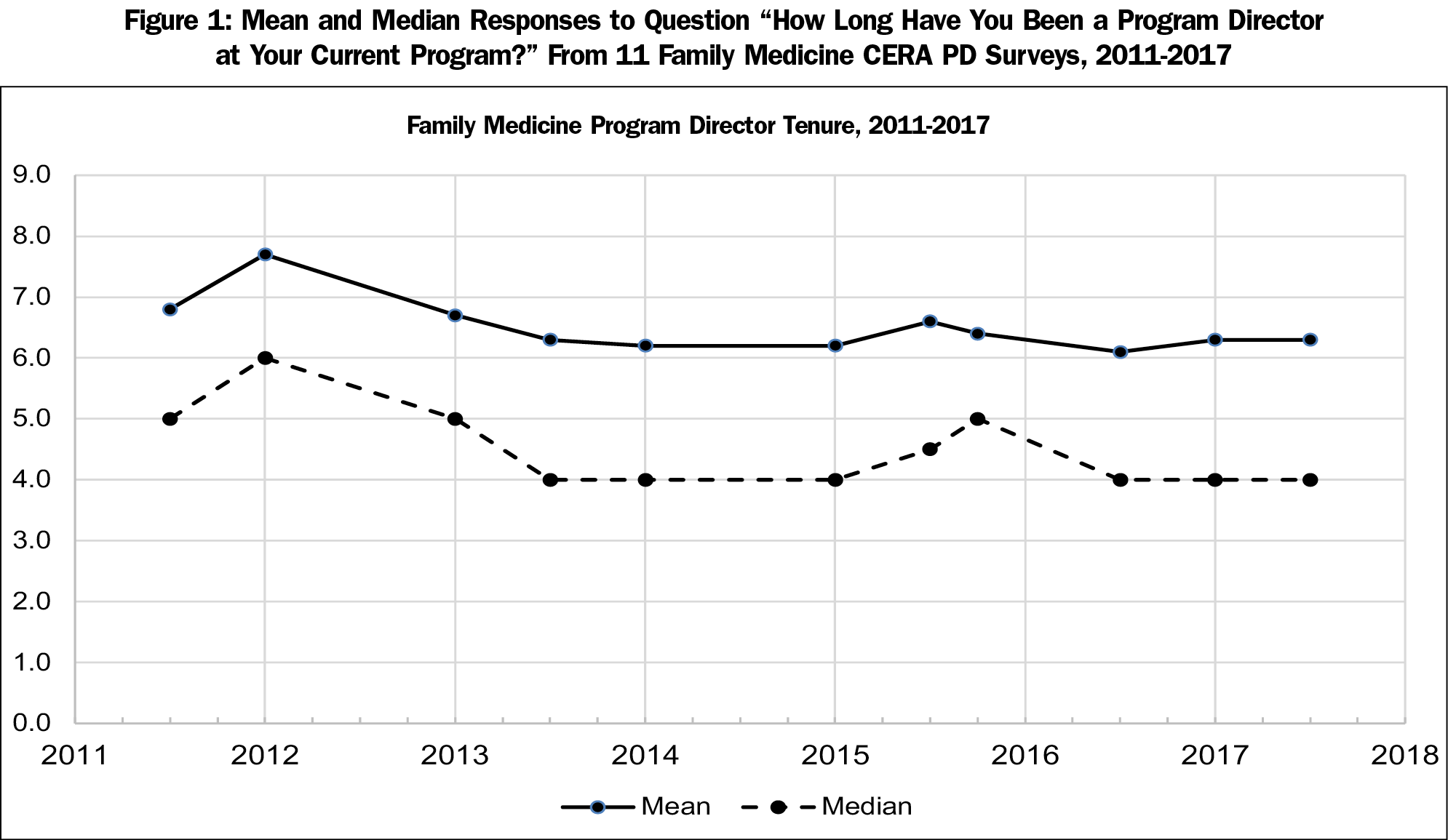

Response rates on CERA PD surveys from 2011-2017 varied from 38% to 54%.10 Figure 1 shows responses to the question: “How long have you been program director at your current program?” Means range from 6.1 to 7.7 years, and medians range from 4 to 6 years. Since 2013, the median PD tenure on the CERA survey has been 4, 4.5, or 5 years. There is no significant difference in values over time (P=0.068).

Figure 2, a histogram displaying 2,577 CERA PD responses over 11 surveys, shows a nonnormal, right-skewed distribution, with a mean of 6.5 years and a median of 4.5 years; 30.5% of responding PDs had been in their position 0, 1, or 2 years.

ACGME data shows that from 2007 through 2017, the mean duration of tenure for family medicine program directors leaving their position was 7 years, and the median 5.2 years.8

We found that the recent mean family medicine PD tenure is 6.5 years and has not changed significantly over the past 7 years. Median program director tenure is lower—4.5 years—meaning that half of PDs have been in their role 4 to 5 years or less.

Our data aligns with data reported by the ACGME 2007-2017, and highlights a challenge facing residencies in many specialties. Of the eight specialties with the most programs (family medicine, internal medicine, general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, pediatrics, diagnostic radiology and emergency medicine), all have median PD tenure shorter than their mean by 1 to 3 years. Four of these specialties have shorter mean and/or median tenure compared to family medicine PDs. The ACGME statement “on average, PDs of ACGME-accredited specialty programs spend approximately 7 years in this role,”8 while true, may be misleading, as median tenure is substantially lower. Many residents will be in their program longer than their PDs.

With the complexity of the PD position, tenure may be an important factor in program excellence. Factors associated with PD turnover include overall job satisfaction, low satisfaction with colleague relationships, high percentage of administrative work, perceiving the job as a stepping stone, and having had formal training to deal with problem residents.9 Our findings highlight the need for specific training and support for PDs in their first few years.

A weakness of our study is that our results are based on surveys with response rates from 38% to 54%. We are unable to determine if there is a difference in tenure between PDs who responded to the CERA survey and those who do not.

The reason that PD tenure is relatively short is not known. Further study is needed to understand why the PD may be “especially vulnerable.”2 Burnout may be a factor.1,2,6,7 Study of PD wellness and how to improve it may yield interventions to improve length of service. PDs may move to positions such as department chair or chief medical officer. An analysis of why PDs depart and what positions they accept after departure would be instructive. Further study could also reveal if short PD tenure truly decreases program quality or the experience of trainees.

In conclusion, median family medicine program director tenure is 4.5 years. Average tenure has not changed in the past 7 years and is similar to that seen in other ACGME-accredited programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Board of Directors of the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors and their Executive Director Deanne St George who inspired this report. Thank you to Stacy Potts, MD. One author (S.B.) would like to thank colleagues, residents, faculty, and staff who have supported him in his program director position for over 7 years.

References

- Neher JO. The unofficial guide to residency director selection. Fam Med. 2006;38(8):577-578.

- Barton LL, Friedman AD. Stress and the residency program director. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148(1):101-103. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170010103024

- Lypson M, Simpson D. It all starts and ends with the program director. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):261-263. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-03-02-33

- Carek PJ, Mims LD, Conry CM, Maxwell L, Greenwood V, Pugno PA. Program director participation in a leadership and management skills fellowship and characteristics of program quality. Fam Med. 2015;47(7):536-540.

- Mitchell K, Maxwell L, Bhuyan N, et al. Program director turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):482-483. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1703

- De Oliveira GS Jr, Almeida MD, Ahmad S, Fitzgerald PC, McCarthy RJ. Anesthesiology residency program director burnout. J Clin Anesth. 2011;23(3):176-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.02.001

- Porter M, Hagan H, Klassen R, Yang Y, Seehusen DA, Carek PJ. Burnout and resiliency among family medicine program directors. Fam Med. 2018;50(2):106-112. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.836595

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Data Resource Book 2007-2017. http://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/Graduate-Medical-Education-Data-Resource-Book. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- Beasley BW, Kern DE, Kolodner K. Job turnover and its correlates among residency program directors in internal medicine: a three-year cohort study. Acad Med. 2001;76(11):1127-1135. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200111000-00017

- Council on Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance. CERA Data Clearinghhouse. http://www.stfm.org/Research/CERA/CERADataClearinghouse. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2228

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

There are no comments for this article.