Background and Objectives: Clinic First residency curricular approaches hold promise as models to successfully prepare primary care residents for future practice. The objective of our study was to estimate the prevalence of the Clinic First model in current family medicine residency training environments, and assess beliefs surrounding curricular structure and postgraduate practice.

Methods: An eight-question survey was conducted among Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD) members in 2017. Data were grouped and analyzed for statistical significance and correlation using analysis of variance, Kendall’s τ, χ2, and Fisher exact test.

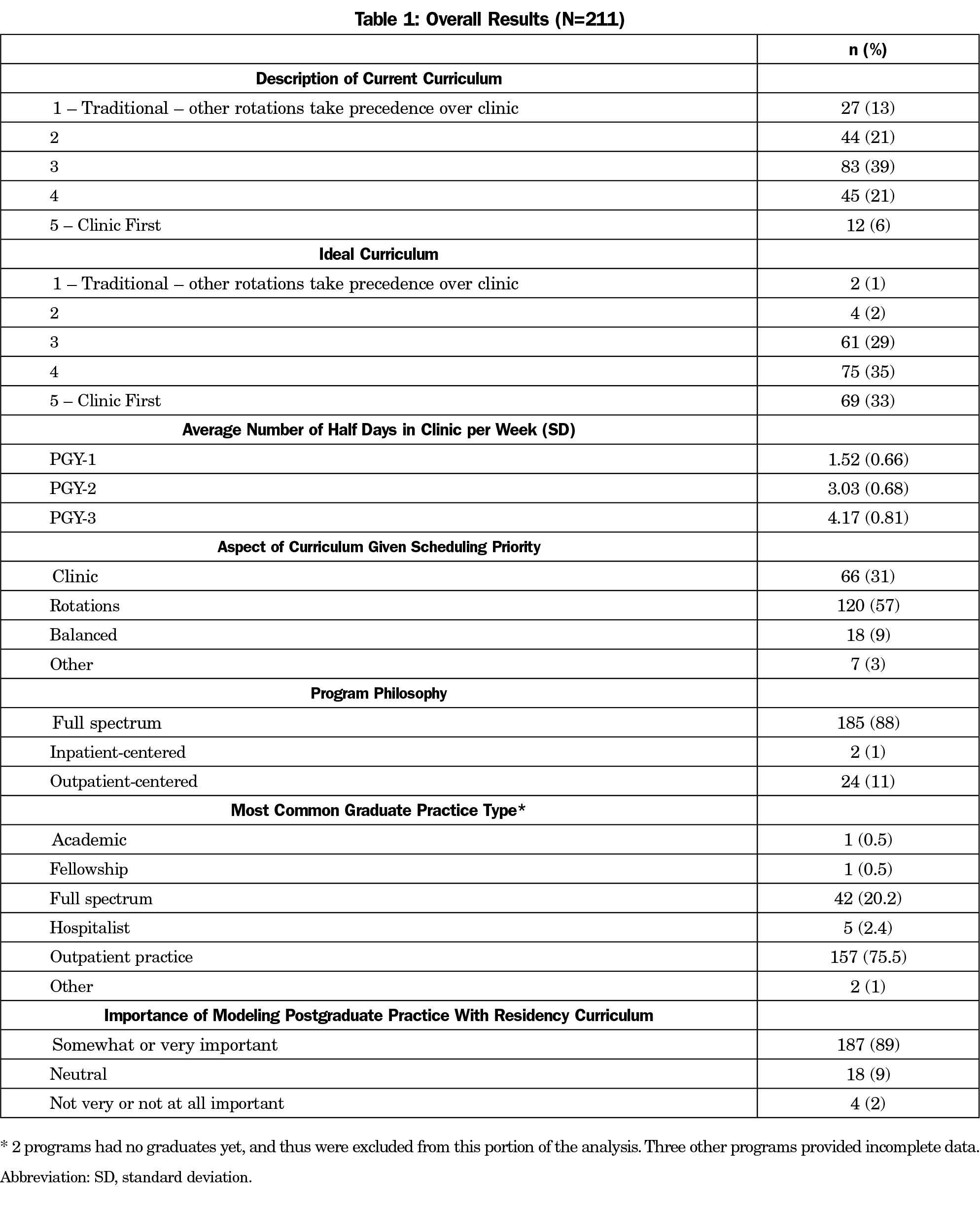

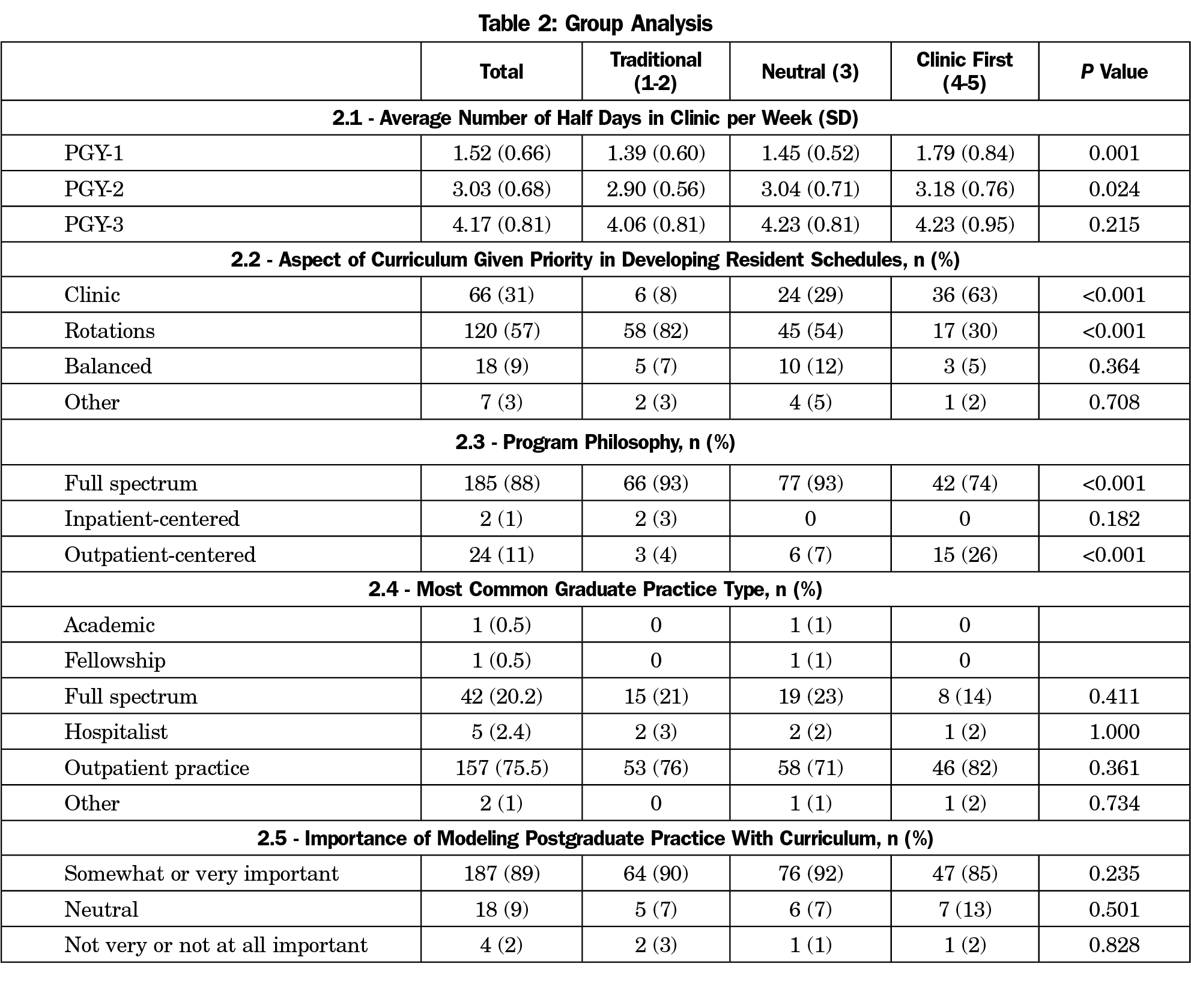

Results: Two hundred-eleven AFMRD members responded to the survey; 27% described their current curriculum as Clinic First; 68% stated that their ideal curriculum is Clinic First. Residents in Clinic First programs spend more half-days in continuity clinic per week compared with traditional programs during PGY1 (1.79, 1.39, P=0.001) and PGY2 (3.18, 2.90, P=0.024). In group analyses, 63% of Clinic First respondents prioritized clinic in developing resident schedules, compared with 8% of traditional respondents (P<0.001). Seventy-four percent of Clinic First respondents described their philosophy as full spectrum, compared with 93% of traditional respondents (P<0.001). Seventy-five percent of respondents listed their graduates’ most common practice type as outpatient practice, and there were no differences between groups (P=0.361). Sixty-one percent of traditional respondents stated that their ideal curriculum is Clinic First (P<0.001).

Conclusions: There is a high level of interest in the Clinic First model as a tool to prepare residents for future practice, but barriers to implementation need to be explored and addressed.

Family medicine residency programs are being challenged to produce physicians who are prepared for the practice of the future. Specifically, future physicians must be equipped with the skills to lead population health initiatives and be capable of effectively leading teams that provide high-quality, cost-effective care to patients within high-functioning patient-centered clinics.1

Residency has been defined as that period of time after medical school when practice habits, attitudes, and professional identity are imprinted on new physicians,2 when requisite patient care experience is obtained, medical knowledge is reinforced and expanded, and interpersonal communication skills are honed. Primary care physicians frequently work in stressful, underresourced clinical environments with little time for appropriate chronic disease management.3 Residents often receive their exposure to outpatient practice in similar settings, namely teaching clinics that are inadequately resourced and dysfunctional.4,5 The 2014 Institute of Medicine report on graduate medical education (GME) highlighted that many physicians lack sufficient training and experience in care coordination, team-based care, costs of care, cultural competence, and quality improvement.6 Additionally, new physicians often have difficulty in managing conditions common to the ambulatory clinical environment, and struggle in performing simple outpatient procedures.7

This discrepancy between what is needed and what is being produced has been attributed to a training gap that currently exists between the inpatient focus of many residency program curricula and the reality that most health care occurs in outpatient settings.8 Whereas a family physician’s practice is most often centered in an outpatient clinic where patients are cared for longitudinally and continuity of care is paramount,9 family medicine residency training is very often hospital-centric, and continuity clinic is often assigned a lower priority than inpatient and other outpatient rotations.10

The Clinic First model is a novel curricular approach that attempts to resolve this disconnect. In this model, ambulatory resident education assumes equal or greater importance than inpatient resident education, continuity and access are emphasized in clinic scheduling, and the teaching clinic provides patient-centered care.11 Clinic First holds promise as a model that can successfully prepare residents for the type of future practice required for health care transformation.12,13 To our knowledge, there has not been an assessment of the nationwide prevalence of Clinic First curricula among family medicine residency programs. The objectives of this investigation were to establish a baseline estimate of the prevalence of such curricular models in current family medicine residency training environments, and to assess beliefs surrounding curricular structure and postgraduate practice.

The authors designed an eight-question survey (see Appendix at https://journals.stfm.org/media/2221/zeller-appendix-fm2019.pdf) in consultation with Clinic First thought leaders and survey design experts, and distributed the survey via the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD) Member Community listserv in November 2017. An initial email provided a link to the REDCap survey platform, which was used for data collection and management. One reminder email was sent to potential participants at a 3-week interval and the survey was closed after 6 weeks. Responses were allowed to remain anonymous, and no detailed program characteristics were collected in order to keep the survey brief. No incentives were provided for survey completion. No formal informed consent was obtained from participants before they completed the survey. Data was exported from REDCap into Microsoft Excel for analysis.

Survey respondents were grouped based on their answers to the first survey question: “On a scale of 1-5, how would you describe your CURRENT residency curriculum?” For this question, “1” was labeled “Traditional – other rotations/experiences take precedence over continuity clinic” and “5” was labeled “Clinic First.” A definition of Clinic First was provided for reference (Figure 1).11 Respondents who chose “1” or “2” were placed in the Traditional group, those who chose “3” were placed in the Neutral group, and those who chose “4” or “5” were placed in the Clinic First group. Respondents were given the opportunity to leave general comments at the end of the survey, and these comments were exported into Excel and reviewed by the authors.

Differences in the number of half days in clinic per week between groups were tested using analysis of variance. Correlation between the respondents’ current group and their ideal group was tested using Kendall’s t. All other analyses among the Traditional, Neutral, and Clinic First groups were tested using χ2 or Fisher exact test for small sample sizes (n<5). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data analyses were completed using R statistical software (R Version 3.0.2). The Greenville Health System Institutional Review Board approved the project.

Overall Results

Two hundred-eleven AFMRD members responded to the survey (206 complete and 5 partial; Table 1). Twenty-seven percent of respondents rated their current curriculum as a 4 or 5 (Clinic First), while 34% rated their ideal curriculum as a 1 or 2 (Traditional). Sixty-eight percent rated their ideal curriculum as a 4 or 5 (Clinic First), while 3% rated their ideal curriculum a 1 or 2 (Traditional). Among all respondents, the amount of time spent in continuity clinic increased from 1.52 half days per week during PGY1 to 4.17 in PGY3.

Overall, 31% of respondents stated that clinic received priority in developing residents’ schedules, while 57% stated that inpatient and/or outpatient rotations received priority. Eighty-eight percent described their program philosophy as full spectrum; 75% stated that their graduates’ most common practice type is outpatient practice; and 89% indicated that it is either “somewhat” or “very” important to them that a program’s educational experience model postgraduate practice.

Group Analysis

Residents in programs described as Clinic First spend more half days per week in continuity clinic than residents in traditional programs, particularly during PGY1 (1.79, 1.39, P=0.001) and PGY-2 (3.18, 2.90, P=0.024; Table 2). Sixty-three percent of Clinic First respondents prioritize clinic in the development of residents’ schedules, while 30% prioritize other rotations over clinic (Table 2). By comparison, 8% of Traditional respondents prioritize clinic in the development of residents’ schedules, while 82% prioritize other rotations over clinic. Regarding most common graduate practice type, there were no statistically significant differences between groups. Eighty-five percent of Clinic First respondents stated that it is either “somewhat” or “very” important to model postgraduate practice during residency, compared with 90% of Traditional respondents.

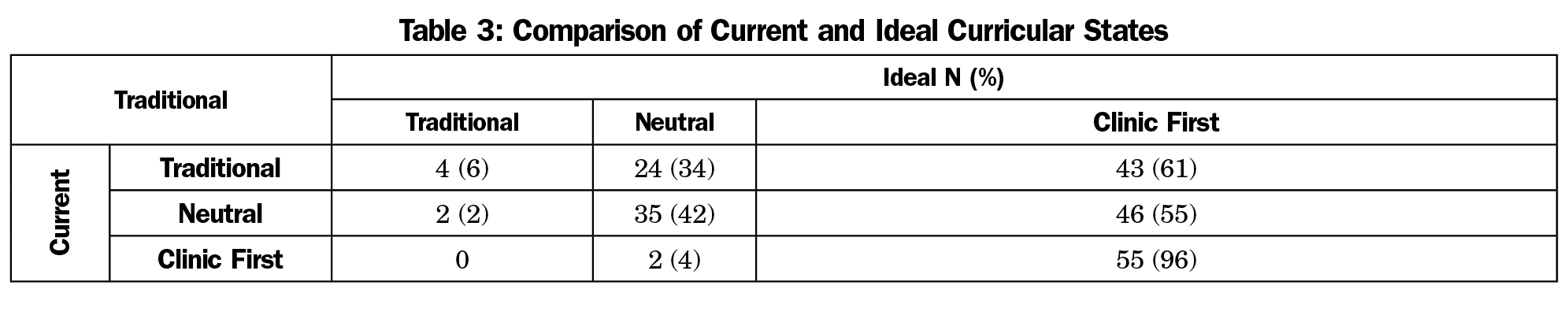

Of the 71 respondents who described their current curriculum as Traditional, 6% stated that their ideal curriculum is Traditional and 61% stated that their ideal curriculum is Clinic First (Table 3). Of the 57 respondents who described their current curriculum as Clinic First, none stated that their ideal curriculum is Traditional and 96% stated that their ideal curriculum is Clinic First. Kendall’s t for this data was 0.264 (P<0.001), demonstrating statistical significance.

Survey Comments

Forty-two respondents (20%) left a comment in the provided open-text box at the end of the survey. Twelve comments were supportive and encouraging, or described a successful implementation of a Clinic First model. Three comments expressed an interest in more information on the Clinic First model. Ten comments described a barrier that prevented implementation or made implementation difficult. Five comments expressed skepticism of or active opposition to the Clinic First model, and 12 comments were general in nature. Barriers described included lack of a clear understanding of the model, lack of felt support from faculty or institution, difficulty reconciling clinic schedule with other rotation schedules, lack of support from residents in the program, lack of funding from CMS or sponsoring institutions to implement the model properly, and a perspective that hospital and specialty rotations are more useful to residents than continuity clinic. Comments skeptical of the Clinic First model included a concern that it would lead to a continued shrinking of the scope of family medicine.

This study reports on the prevalence of AFMRD members who describe a Clinic First program curriculum. The results uncover a discrepancy between current and ideal states for many Traditional respondents. Conversely, respondents that are currently implementing a Clinic First model are highly likely to describe it as their ideal curriculum. For many respondents, there appears to be doubt as to whether a traditional curricular approach is ideal, and a high level of interest in Clinic First as a preferred curricular state. One possible explanation for this level of interest is that many respondents view the Clinic First model as a tool to better prepare residents for future practice. This is suggested by the findings that most respondents’ programs are producing graduates who primarily go on to practice in outpatient settings, the broad general agreement on the importance of modeling postgraduate practice during residency, and the clear evidence from this study that Clinic First models increase the amount of time spent in continuity clinic.

Survey results fell short of validating the concern expressed in comments that widespread adoption of a Clinic First curricular model will contribute to a collective narrowing of the specialty’s scope of practice. While Clinic First respondents were less likely than their Traditional counterparts to describe their program philosophy as full spectrum, a majority of Clinic First respondents still consider their programs to be full spectrum in philosophy. More importantly, no significant differences existed between Clinic First and Traditional respondents with regard to most common graduate practice type. So while there may be differing definitions of the term “full spectrum,” survey results suggest that widespread adoption of a Clinic First model would not necessarily lead to a reduction in scope of practice among graduates, and that a Clinic First model simply prioritizes continuity clinic, the aspect of a program’s curriculum that best models most graduates’ future practice.

Some of the data suggest that there is confusion regarding implementation of the model. Specifically, while 63% of Clinic First respondents prioritize clinic or describe a balanced approach to developing resident schedules, 30% still state that they prioritize other rotations over clinic. Programs may benefit from more education on implementation of a Clinic First model in which ambulatory resident education assumes equal or greater importance than inpatient resident education.

The discrepancy between current and ideal curriculum detected by this study indicates that, while there is a high level of interest, significant barriers exist to implementation of a Clinic First model. While a full analysis of potential barriers is beyond the scope of this study, comments left by some respondents suggest that barriers to implementation fall into categories similar to those found in studies of other family medicine curricular change.14 Future studies are needed to work toward identifying and overcoming specific barriers to implementation of a Clinic First model. This particular study identified 57 AFMRD members who identify their program curriculum as Clinic First; so future research could include prospective studies of the effectiveness of the model within this subpopulation of programs, and could include measures of graduates’ readiness for practice and resulting scope of practice.

Study limitations include use of self-reported data and the nonrandom sampling method employed to gather responses, both of which may have introduced bias. Post hoc groupings (Clinic First, Neutral, Traditional) derived from the data in the first survey question also constitute a limitation, as use of a 5-point scale could have led to a variety of understandings or interpretations of the response options. Different interpretations of terms for which a rigorous definition was not provided may have introduced bias or caused confusion. Additionally, even though a definition was provided, lack of a generally accepted and precise definition of Clinic First likely affected the data. The survey may not have reached all programs, since some program directors and faculty may not be members of the AFMRD, or may not be active on the online Member Community (listserv). Due to the anonymous nature of the survey and the fact that multiple faculty from the same program can participate on the AFMRD listserv, it is possible that some responses described the same program. The survey did not attempt to ascertain program characteristics such as geographic location, size, university affiliation, or the presence of other residencies in the learning environment, and while this kept the survey brief, it also did not allow for further analysis of programs that are attempting to implement a Clinic First curriculum. Survey participation could have been improved by using the Council of Academic Family Medicine Education Research Alliance survey. Future studies should take advantage of established platforms for data acquisition in order to improve the accuracy of the data.

In conclusion, this survey-based study found that a small percentage of AFMRD members describe current implementation of a Clinic First curricular model, yet a majority consider a Clinic First curriculum to be ideal, including a majority who describe current implementation of a more traditional curriculum. While there is a high level of interest in this model as a potential tool to better prepare residents for future practice, barriers to implementation must be explored and addressed.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Margae Knox, MPH, Research Analyst with the Center for Excellence in Primary Care at University of California, San Francisco, for assistance in survey development.

References

- Phillips RL Jr, Bitton A. Tectonic shifts are needed in graduate medical education to ensure today’s trainees are prepared to practice as tomorrow’s physicians. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1444-1445. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000477

- Larson T, ed. Innovations in Graduate Medical Education: Aligning Residency Training with Changing Societal Needs. New York: Josiah Macy Jr Foundation; 2016. http://macyfoundation.org/docs/macy_pubs/JMF_2016_Monograph_web.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2019.

- Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):799-805. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0026

- Nadkarni M, Reddy S, Bates CK, Fosburgh B, Babbott S, Holmboe E. Ambulatory-based education in internal medicine: current organization and implications for transformation. Results of a national survey of resident continuity clinic directors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):16-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1437-3

- Warm EJ, Leasure E. Primary care and primary care training: mirror images. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):5-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1561-0

- Institute of Medicine. Eden J, Berwick D, Wilensky G, eds. Graduate Medical Education that Meets the Nation’s Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014.

- Crosson FJ, Leu J, Roemer BM, Ross MN. Gaps in residency training should be addressed to better prepare doctors for a twenty-first-century delivery system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(11):2142-2148. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0184

- Bodenheimer T, et al. High-functioning Primary Care Residency Clinics: Building Blocks for Providing Excellent Care and Training. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2016.

- Phillips RL Jr, Brundgardt S, Lesko SE, et al. The future role of the family physician in the United States: a rigorous exercise in definition. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(3):250-255. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1651

- Wieland ML, Halvorsen AJ, Chaudhry R, Reed DA, McDonald FS, Thomas KG. An evaluation of internal medicine residency continuity clinic redesign to a 50/50 outpatient-inpatient model. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1014-1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2312-1

- Gupta R, Barnes K, Bodenheimer T. Clinic First: 6 Actions to Transform Ambulatory Residency Training. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(4):500-503. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-15-00398.1

- Barnes K, Morris CG. Clinic First: Prioritizing Primary Care Outpatient Training for Family Medicine Residents at Group Health Cooperative. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1557-1560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3272-z

- Kim JG, Morris CG, Ford P. Teaching Today in the Practice Setting of the Future: Implementing Innovations in Graduate Medical Education. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):662-665. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001510

- Fernald DH, Deaner N, O’Neill C, Jortberg BT, degruy FV III, Dickinson WP. Overcoming early barriers to PCMH practice improvement in family medicine residencies. Fam Med. 2011;43(7):503-509.

There are no comments for this article.