Background and Objectives: The Family Medicine for America’s Health Workforce and Education Team aims to increase the number of medical students choosing family medicine to address the projected primary care physician shortage. This aim can be achieved by developing a well-trained primary care workforce. Our student- and resident-led FMAHealth work group aimed to identify factors that influenced fourth-year medical students’ choice to become family physicians. The secondary objective compared such factors between the 10 medical schools with the highest percentage of students matching into family medicine and non-top 10 medical schools.

Methods: Fourth-year medical students nationwide participated in 90-minute virtual focus groups. Reviewers coded deidentified transcriptions and identified key themes and subthemes that were found to influence student choice.

Results: Fifty-five medical students participated in focus groups over a 2-year period. Three key themes were found to influence students: perspective, choice, and exposure. Subthemes included: (1) the importance of high-quality preceptors practicing full-scope family medicine, (2) the value of a rural experience, and (3) institutional support to pursue family medicine. Physician compensation and loan repayment concerns were not major factors influencing student choice.

Conclusions: Many factors influence student choice of family medicine including preceptors, clinical exposures, and institutional support. These factors varied by institution and many were found to be different between top 10 and non-top 10 schools. Addressing these factors will help increase students’ choice of family medicine and reduce the primary care shortage.

The United States will face a significant shortage of primary care physicians due to ongoing population growth, aging of the US population, and retirement of practicing physicians. A recent study estimated that the US will experience a shortage of over 33,000 primary care physicians by 2035.1 While advocacy efforts have focused on increasing the number of primary care residency positions, attention must also be given to whether these positions are being filled. According to the National Resident Matching Program, 119 of the 3,629 family medicine residency positions offered in 2018 went unfilled and only 44.9% went to US medical school graduates.2

The Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) Workforce and Education Team is dedicated to increasing the number of medical students choosing family medicine to address the projected primary care shortage. While prior quantitative studies have suggested that exposure to family medicine through required family medicine clerkships, rural experiences, and pipeline programs lead to increased knowledge and improved attitudes toward family medicine, impact on ultimate specialty choice is mixed.3-7 A conceptual framework for primary care specialty choice was also developed for students based on their matriculation predispositions toward primary care and the many categories of influence that may affect them, including but not limited to lifestyle, financial considerations, student interests and perceptions, and curriculum experience.8

To further understand the factors influencing specialty choice, the FMAHealth work group conducted semistructured focus groups with allopathic medical students across the United States. Focus groups were designed primarily to elucidate the factors affecting student choice of family medicine with a secondary aim to compare perspectives of students from the 10 US medical schools with the highest percentage of students applying to family medicine residencies (Table 1) with those from other US allopathic medical schools (non-top 10 schools).

Recruitments

Institutional review board approval was obtained through Ellis Medicine.* Between November 2016 and March 2018, fourth-year US allopathic medical students matching into any specialty were invited to participate in one of several nationwide focus groups. The work group recruited students through multiple contact sources including the Family Medicine Interest Group (FMIG) Network, class Facebook groups, FMIG faculty advisors, and sign-ups provided at family medicine conferences. A $10 gift certificate to Amazon was offered to all participants.

Focus Group Structure

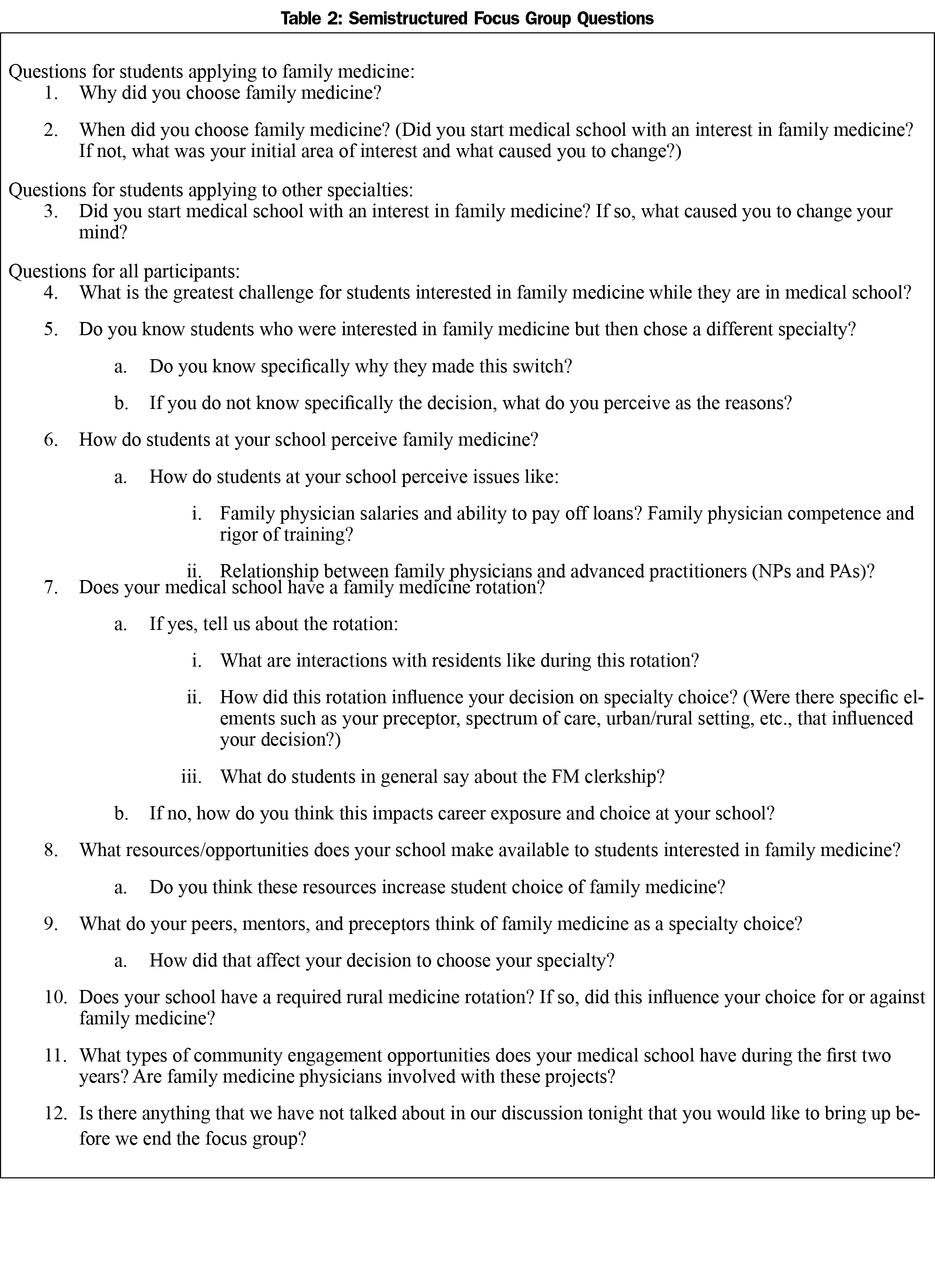

Prior to the focus groups, participants consented to participation including audio recordings and deidentified transcriptions. Students participated in semistructured 90-minute virtual sessions moderated by a work group leader. Discussion included 10-12 open-ended questions (Table 2) to identify what factors that influenced students’ specialty choice. Focus group size ranged from two to six participants.

Data Analysis

Qualitative content analysis with an inductive coding approach was used to analyze the first cohort of focus groups. Deidentified transcripts were reviewed by two to three coders who independently noted themes and subthemes among the group responses. The work group discussed discrepancies between coders and reviewed the themes until a consensus was reached. The finalized themes and subthemes were then applied to the analysis of subsequent focus groups.

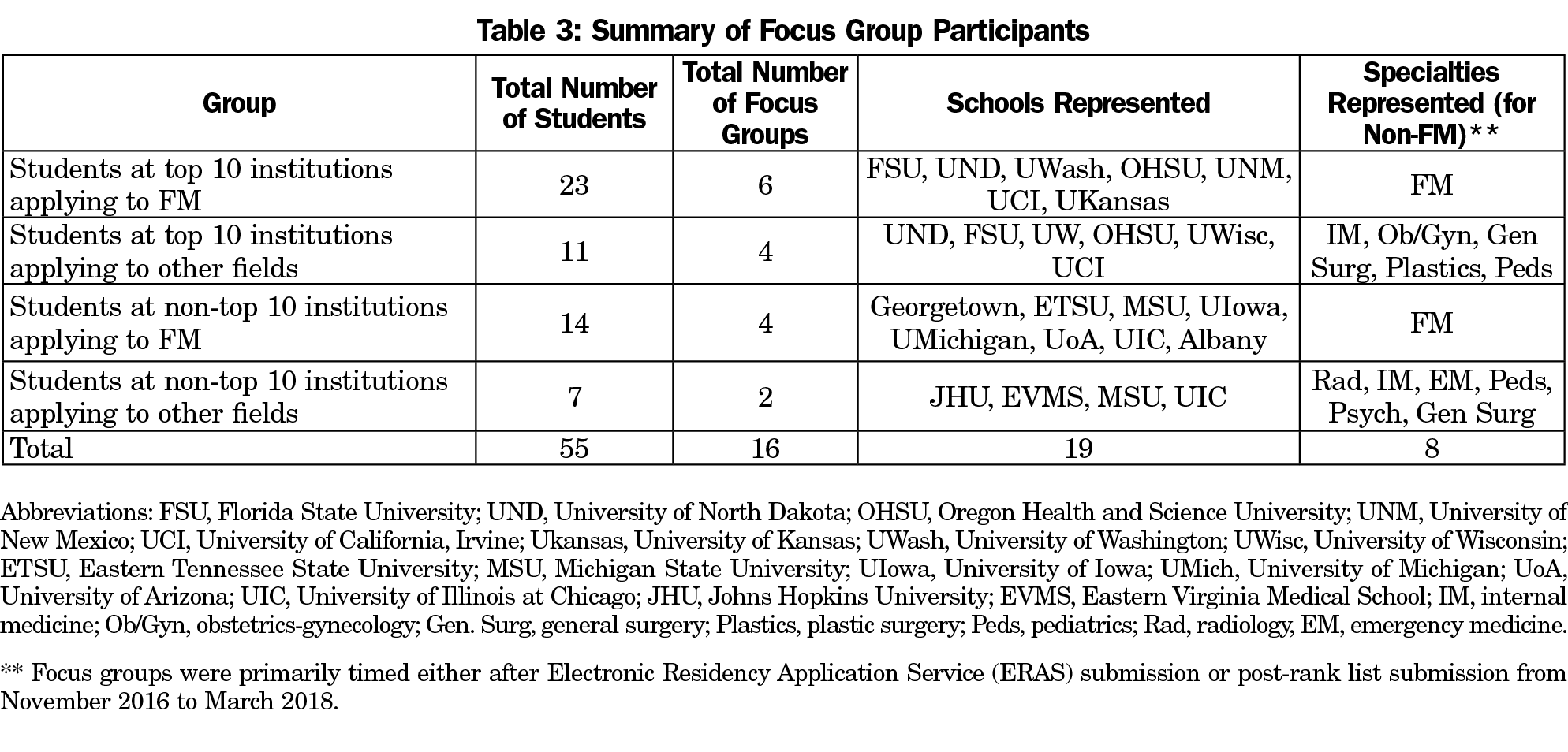

Focus group sessions were conducted from November 2016 through March 2018 with 55 medical students from 19 institutions participating. Students fell into one of four groups listed in Table 3.

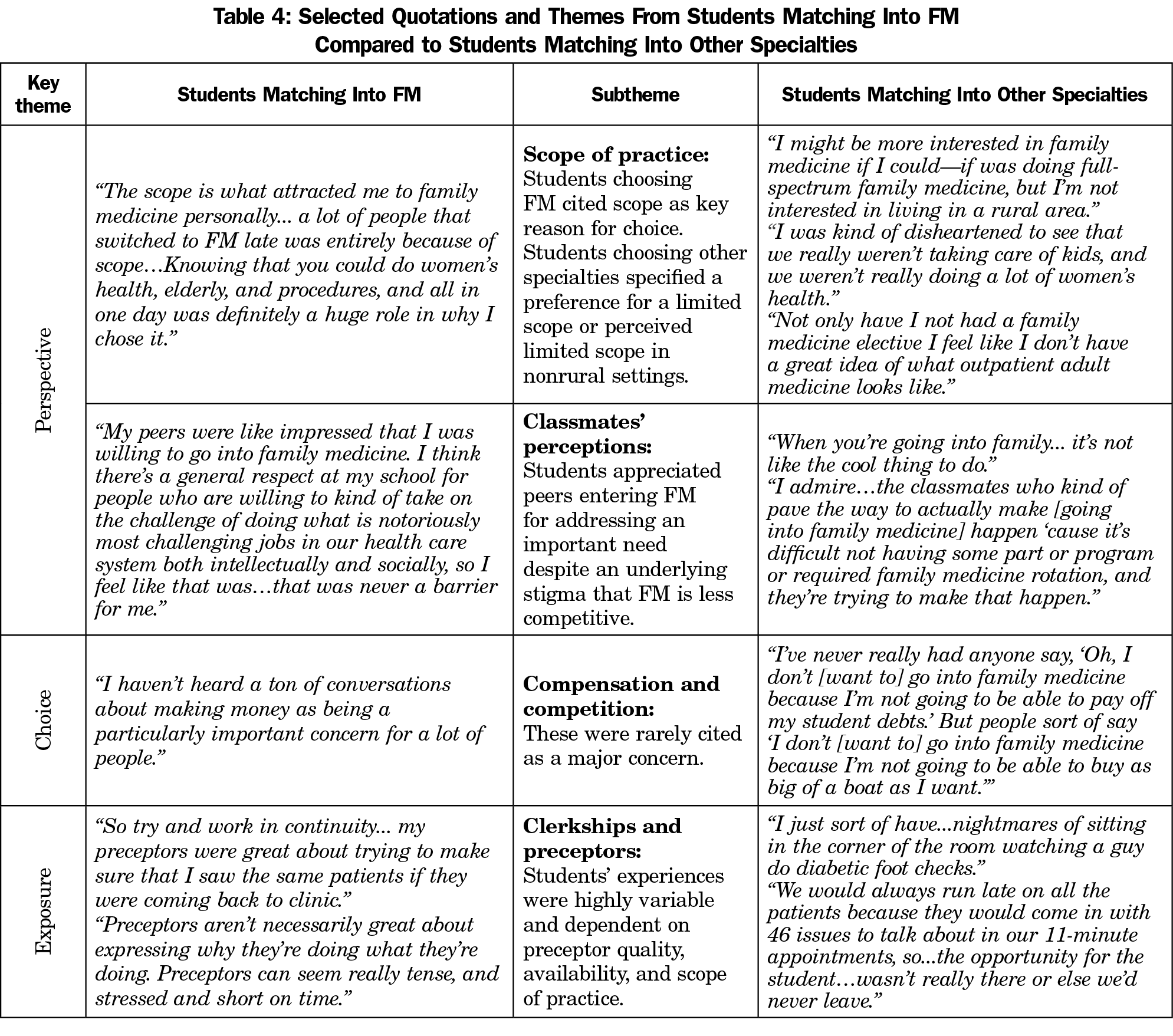

The three key themes identified as factors influencing student choice of family medicine were perspective, choice, and exposure. Perspective included the students’ view of family medicine as well as views from mentors, faculty, specialists, family members, and peers. Choice encompassed the students’ initial interest in family medicine followed by barriers or encouragement encountered throughout their medical training. Exposure related to students’ experiences on their family medicine rotations, the institution’s family medicine culture, and opportunities to explore family medicine. Themes are illustrated through key quotes in Tables 4 and 5. Subthemes and summarization of student comments are highlighted in the middle column.

Three key issues were echoed across focus groups. The most consistently identified factor was the need for high-quality family medicine preceptors who express enthusiasm for the field and practice full-scope family medicine exhibiting the breadth of this specialty. The second highly praised factor was the value of a rural family medicine experience, mainly due to the broad scope of practice. Lastly, students reiterated the importance of top-down institutional support of primary care, specifically family medicine. This was best highlighted when family medicine faculty were integrated into the preclinical curriculum.

Participants from top 10 institutions, both applying into family medicine as well as other specialties, held family physicians in high regard. These students reported a better understanding of family medicine due to their early exposure throughout the preclinical curriculum as well as on clinical rotations. They also echoed the importance of influential preceptors and felt that the mission of their schools placed a stronger emphasis on primary care. Students from the top 10 schools specifically highlighted the discrepancies between urban versus rural family physician scope of practice and were less likely to pursue family medicine if they planned to practice in an urban setting.

Students from the non-top 10 schools explicitly highlighted institutional stigmas against family medicine. These students spoke about the underappreciation of family medicine, the lack of prestige of the specialty, and the encouragement of competitive students to choose other fields. Students also reported less exposure to family medicine and were more likely to perceive the scope as limited to outpatient chronic disease management. Compared to top 10 schools, public health and social justice issues were more often mentioned by these students as motivation to choose family medicine. Physician compensation was not found to be a driving factor amongst students in any group however was mentioned more often by these students.

Regardless of institutions, students choosing other specialties agreed that administrative burden and the perceived broad scope of family medicine pushed them away from family medicine.

Limitations of this study included unequal representation from students not choosing family medicine, lack of representation of all top 10 medical schools, lack of generalizability between schools, exclusion of osteopathic medical students and international medical graduates, small population size, and subjectivity of qualitative research analysis. The investigators also had limited training in qualitative focus group research prior to this study.

In conclusion, students from all groups consistently highlighted the importance of having high-quality preceptors and rural family medicine experiences as positive factors for choosing family medicine. The positive and negative top-down institutional influences are also important in student choice. These concepts are similar to those highlighted by the conceptual framework developed by Bennett and Phillips.8 Important barriers facing students from non-top 10 schools included the lack of exposure to family medicine and the need for family physician mentors to model a broad scope of practice. In addition, students not pursuing family medicine described how the broad scope of practice and underappreciation of family physicians deterred them from pursuing the specialty.

* Ellis Medicine is a teaching hospital in Schenectady, New York affiliated with the Ellis Family Medicine Residency Program. Coauthor KrisEmily McCrory is on faculty at this residency (IRB#-IRB00008111; FWA-FWA00017254).

Acknowledgments

Data from this manuscript were presented at the AAFP National Conference for Students and Residents in 2017, and Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Medical Student Education Conference in 2018.

Financial Support: Amazon gift cards were funded through Family Medicine for America’s Health.

References

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the residency expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):107-114. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1760

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2018 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018.

- Kane KY, Quinn KJ, Stevermer JJ, et al. Summer in the country: changes in medical students’ perceptions following an innovative rural community experience. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1157-1163. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299fb5d

- Phillips J, Charnley I. Third- and Fourth-Year Medical Students’ Changing Views of Family Medicine. Fam Med. 2016;48(1):54-60.

- Rabadán FE, Hidalgo JL. Changes in the knowledge of and attitudes toward family medicine after completing a primary care course. Fam Med. 2010;42(1):35-40.

- Wilkinson JE, Hoffman M, Pierce E, Wiecha J. FaMeS: an innovative pipeline program to foster student interest in family medicine. Fam Med. 2010;42(1):28-34.

- Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Wortman JR. Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: a systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):235-243. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318163789b

- Bennett KL, Phillips JP. Finding, recruiting, and sustaining the future primary care physician workforce: a new theoretical model of specialty choice process. Acad Med. 2010;85(10)(suppl):S81-S88. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4bae

- Kozakowski SM, Fetter G Jr, Bentley A. Entry of US Medical School Graduates Into Family Medicine Residencies: 2014-2015. Fam Med. 2015;47(9):712-716.

There are no comments for this article.