Background and Objectives: Family physicians are increasingly making or contemplating various methods of practice transformation, but most report significant barriers to making that transition. Given strong interest in practice transformation, and perceived barriers to doing so, it is important to examine how some practices are implementing changes and overcoming barriers. In this project, Family Medicine for America’s Health Practice Team learned from practices across the United States that are transforming and experiencing the benefits of working in a comprehensive, value-based practice. The objectives of the project were to identify drivers of transformation to value-based care and ways of working with drivers to mitigate potential barriers, and to determine relationships between practice transformation and joy of practice.

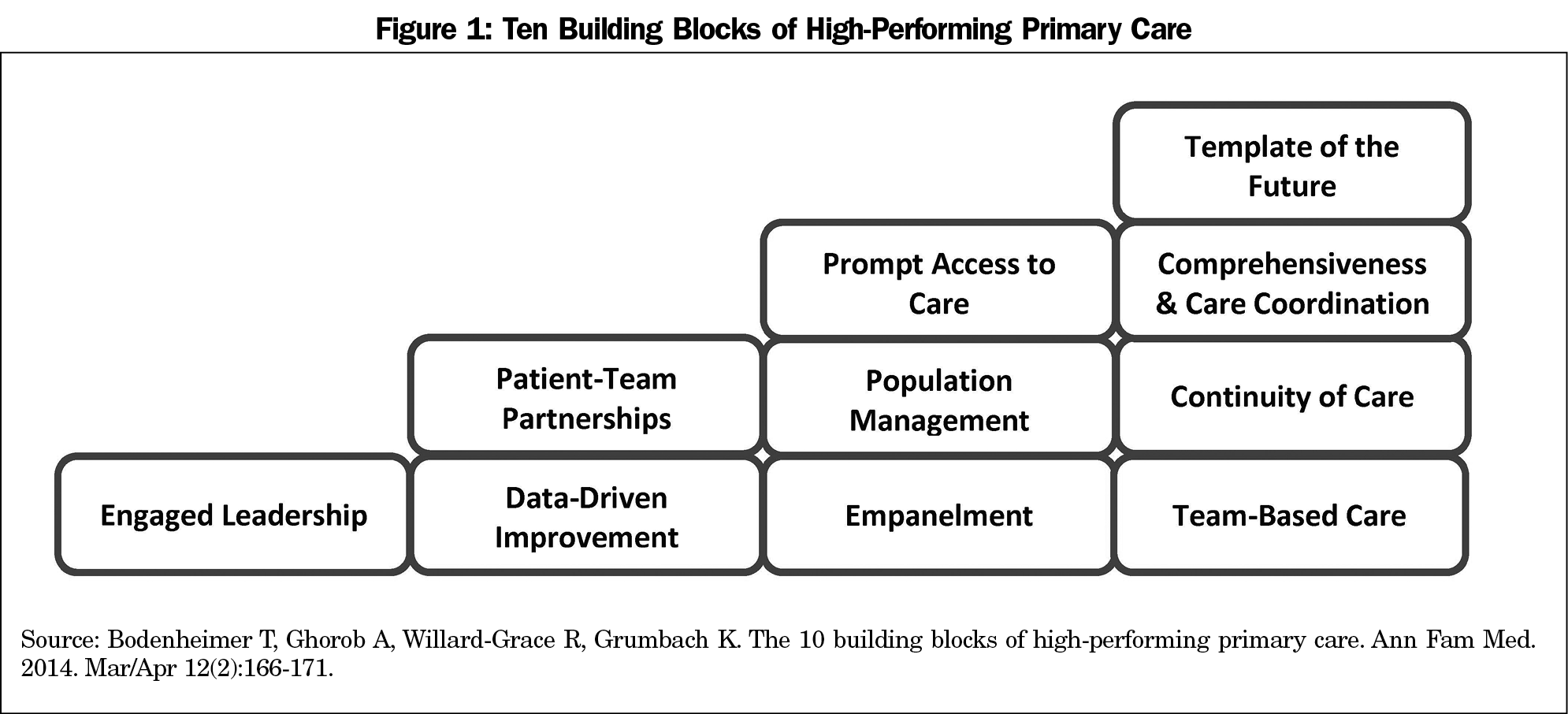

Methods: Fifteen practices of varying size and type from 11 states participated in this project. Practices were sent a short-answer survey about their practice, transformation, and payment structure. Next, practices participated in a 45-60-minute deep-dive interview. All surveys and interviews were iteratively coded to identify themes using Thomas Bodenheimer, MD, et al’s building blocks of high performing primary care framework.

Results: Engaged leadership, data-driven improvement, team-based care, and comprehensiveness and care coordination were primary drivers of transformation, with payment as a needed foundation. Practice transformation helped meet the triple aim and was correlated to joy of practice.

Conclusions: Practices are transforming to comprehensive value-based care delivery and experiencing greater joy in practice; but payment reform is required to spread and sustain practice transformation.

Family physicians are increasingly making or contemplating various methods of practice transformation. A 2017 survey conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) found over half of US family physicians are actively pursuing or developing capabilities to transition to value-based models. In spite of increasing interest, over 90% of family physicians reported facing significant barriers to value-based care delivery and payment.1

Given the increasing interest in practice transformation,2,3,4,5 it is important to examine how practices are implementing changes and overcoming barriers. Throughout the United States there are bright spots in practice transformation that are achieving varying degrees of success in their efforts. Building upon previous qualitative research into the benefits of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) and practice transformation,3,6 Family Medicine for America’s Health’s (FMAHealth) Practice Tactic Team7 sought to identify and learn more about the practice transformation experiences of primary care practices across the United States. The project’s objectives were to identify drivers of transformation and ways of working with drivers to mitigate potential barriers, and to determine relationships between practice transformation and joy of practice. Understanding drivers of practice transformation can provide guidance for practices transitioning their practices to, or contemplating a move toward, value-based care.

This project builds on Thomas Bodenheimer, MD, et al’s 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care framework8 as outlined in Figure 1.

Selection and Description of Participants

Practices from across the United States were recruited to participate in this project, and were identified by peer and self-nominations, FMAHealth board and tactic team members, and a snowball technique utilizing practices identified early in the process to identify others. This project sought practices with different and innovative practice models, with varying percentages of value-based payments, and located in different geographic markets across the United States.

Fifteen practices participated in the project. The practices are located in 11 states: Akansas, California (4), Florida (2), Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania. Practices varied in size from single-physician practices to large practices including one with 14 practice site locations. Practice models differed across sites and included traditional fee-for-service practices (FFS), accountable care organizations (ACO), federally qualified health centers (FQHC), direct primary care practices (DPC), an academic residency practice, and practices participating in the comprehensive primary care9 (CPC) and comprehensive primary care plus10 (CPC+) initiatives through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Neither practices nor participants were compensated for participation.

Materials and Procedures

Practices completed a survey that provided background information about their practice and context for further discussion during the interview. The survey, adapted from Suzanne Houck’s research, contained 37 short-answer responses about practice, practice transformation, and payment structure.11

After practices returned the surveys, interviews were scheduled with leaders at each practice and conducted via conference call. The interview protocol included a brief introduction and several questions about leadership, activities to sustain improvements, approach to prevention and chronic illness, challenges to sustain improvements, advice for others, joy in practice, and additional themes. Each interview lasted 45-60 minutes and was recorded and transcribed. The University of Alabama Institutional Review Board granted the project exempt status.

Analysis

To ensure that the building blocks of a high-performing primary care model8 was an appropriate analytic framework, four project team members blind to the building blocks framework inductively and iteratively coded the survey and interview responses from four of the practices.12 After several analytic iterations, with one exception, discussed below, team members identified themes congruent with the building blocks framework. Given these initial findings, the research team adopted the building blocks as its analytic framework and iteratively coded all surveys and interviews.

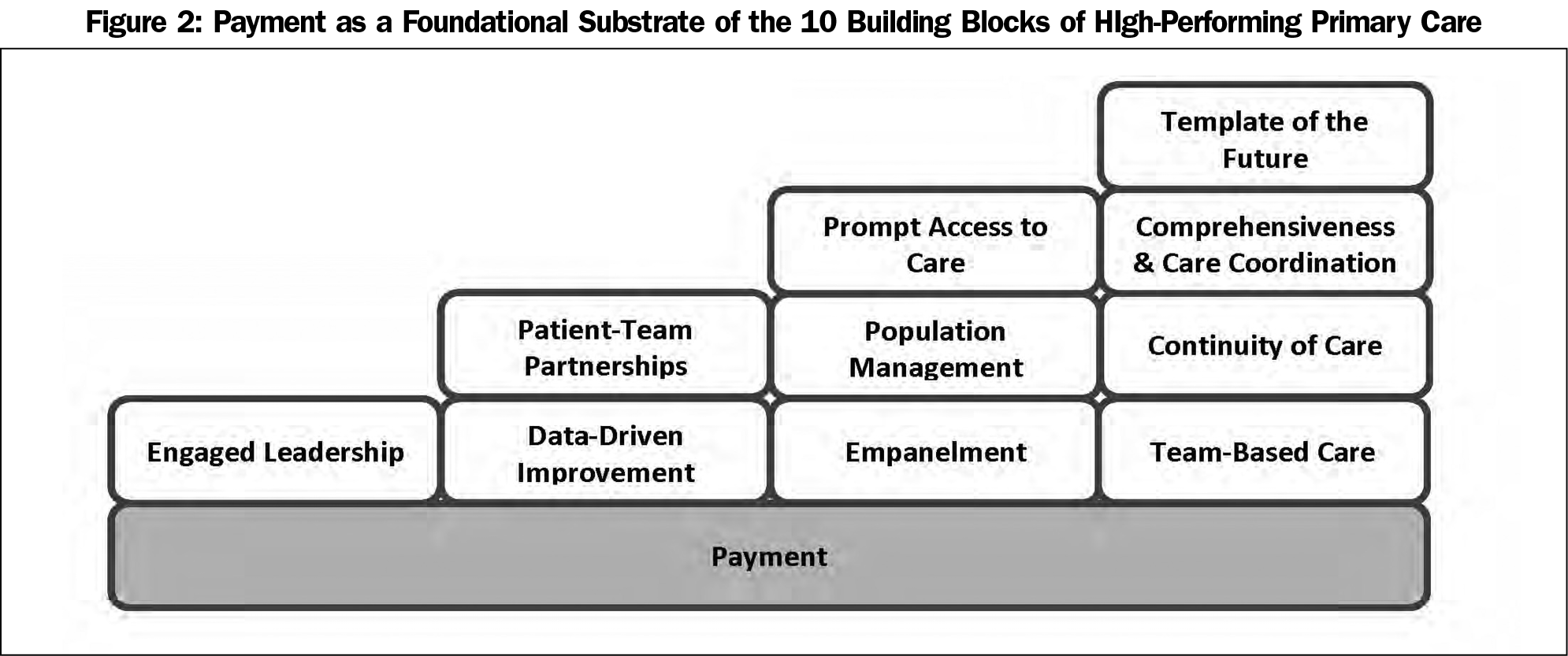

Payment

The theme of payement did not fit within the building blocks framework. Discussion of the importance of payment as part of practice transformation was present in all interviews, and 87% of practices indicated that physician compensation directly affected practice transformation efforts. Practices from this project indicated that payment acts as a foundational driver and foundational barrier to implementing and sustaining practice transformation to value-based care.

Payment as a Foundational Driver of Transformation to Value-Based Care. The DPC and ACO practices interviewed removed insurers from their payment models and created a per-member-per-month (PMPM) fee for primary care services. The resulting steady stream of income and decreased administrative burden allowed the primary care teams to invest more time and resources into population health and prevention, and provided greater flexibility for patient encounters (eg, face-to-face, texts, over the phone, and off hours). Increased payments to ACO, CPC, CPC+, and FQHC practices created opportunities for increased team-based care, comprehensiveness and care coordination, patient-team partnerships, and investments in infrastructure to better implement data-driven improvements. Even within FFS practices, restructured payment allowed for increased team-based care and care coordination, which made it possible to hire additional medical assistants and care coordinators.

Payment as a Foundational Barrier Blocking Transformation to Value-Based Care. Several practices indicated the current payer system and lack of reimbursement were the biggest challenges to transformation. Among practices in this project, FFS was the dominant payer model. Four practices were 100% FFS. Nine practices were FFS dominant, with capitated or quality payment structures from 5% to 25%. Only the ACO practice with 94% capitated payment through payer agreements, and the DPC practice with 100% PMPM, offered a dominant value-based payment structure.

In addition, payment was identified as the foundational barrier blocking transition to value-based care in the future. FFS-dominant practices indicated they had no plans to expand their percentage of value-based payment contracts. Findings from these interviews and other studies suggest that practices are preparing to transition to increased value-based care, but the risk is too great given an uncertain reimbursement climate.1,4,5

In light of the felt risk, practices discussed the challenge of keeping the lights on, to keep their practices afloat, and as an ethical responsibility to their patients. As one practice stated:

You wanna be a little bit ahead of the curve, but you certainly don’t wanna be too far ahead that your internal reality is different than your external reality … [The compensation committee] are certainly willing to push value-based compensation into the double digits. Maybe 20% to 30%, but we do not wanna get ahead of our external reality, but we also wanna be ready for it. So if Medicare does pivot that aggressively, we’re ready for it. If it does not, we will keep this—I’d say we’ll be between 5% and 10% value-based compensation for the next 3 to 5 years unless there’s an external force that shifts this faster.

Because payment acts so strongly as both a driver and a barrier, we propose adding payment as a foundation to the achievement of Bodenheimer’s building blocks of high-performing primary care framework (Figure 2).

Engaged Leadership

All practices interviewed discussed engaged leadership as a necessary precursor and primary driver of practice transformation. Transformation did not happen by chance; it was initiated by a leader who recognized the importance of value-based care and was sustained through engaged leadership. As one practice said,

There’s absolutely no way you can transform a practice without having leadership fully bought in and then engaging other leaders in the organization.

Practices described engaged leadership along three dimensions: strategy, communication, and creating a culture of improvement. Each dimension was consistently discussed when asked about activities important to sustaining practice improvements, and as advice practices would give to others seeking to transform.

Strategy included the vision, goals, and planning for practice transformation. Approaches to strategy differed across practices. Some were centralized and top-down, others were team-based, and CPC and CPC+ practices relied on pilot program guidelines. Regardless of method, engaged leaders carved out time for on-going strategy review. As one practice representative stated,

Strategy needs to be constantly reevaluated because of the shifting dynamics in health care, so that it remains transformational as well as realistic.

Every practice discussed the importance of a systematic communication process to spread vision, rationale, and changes across the organization, and for communication among teams within the organization. One practice representative stated,

Really communicate … it’s not just announcing things to people … communication has to have a process of always kinda filtering through the organization, and it is really challenging to do that in a day-to-day practice.

Another was more succinct, “Communicate, communicate, and communicate. If you don’t the process will fall on its face.”

A culture of improvement was identified as necessary to sustain change. When asked if there was anything they would do differently if beginning again, several practices stated they would have invested in creating a stronger culture of quality improvement. Others stated that dedicated time and commitment to quality were key activities to sustaining improvements. All but two practices had a formal improvement process. Practices used different methods: Plan-Do-Study-Act, LEAN, Six Sigma, and Kaizen. As one practice stated, it does not matter what method a practice chooses as long as quality improvement is effectively embedded within a practice’s culture.

Data-Driven Improvement

Data-driven improvement systems were identified as key drivers for the other building blocks and for a culture of improvement. Practices discussed electronic health records (EHRs) as a burden that required physicians to become information technology specialists but conceded EHRs are a necessary evil. Several practices described struggling to utilize EHRs to pull, organize, analyze, and effectively use data. To overcome this potential obstacle, two practices hired third-party services and consultants to manage their data and sustain their transformation practices. Other practices had to modify documentation and coding so the data could be pulled and used effectively. Those practices stated that, if beginning again, they would pay greater attention to the collection, organization, and use of data at the earliest stages in their transformation process.

Empanelment, Population Management, and Patient-Team Partnerships

All practices empaneled their patients, and all but three actively managed panel size. All but one had population management practices. Examples of population management practices include patient registries, health risk assessment tools, dedicated resources to care for complex patients, structured approaches for prevention and chronic illness care, and patient-centered medical home certification. All but two practices had organized systems and programs to form patient-team partnerships that included health educators, group education programs, self-management, and quarterly patient meetings. No practices reported struggling with these building blocks.

Team-Based Care, Comprehensiveness and Care Coordination

All practices interviewed had moved to team-based care and indicated it was a primary driver of practice transformation. The most common team configuration was one physician and one medical assistant, often in conjunction with a registered nurse to provide care coordination. There were numerous other configurations, with smaller teams working in larger pods, and with various team configurations including combinations of physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, care managers, care coordinators, chronic care coordinators, patient service representatives, nurses, medical assistants, and specialty disciplines (pharmacy, social work, psychology, etc). The goals and indicators of success for teams were for each team member to work to their highest scope of practice, increase workplace efficiency, and maintain the highest quality of patient-centered care.

Increased team-based care strongly influenced care coordination. The presence of medical assistants, care coordinators, and other team members, in conjunction with population management tools, created the opportunity to better understand, manage, and care for individual patients and different populations. Care coordination, in turn, contributed to providing comprehensive care. Most practices were unable to support comprehensive services in house. Therefore, practices relied on care coordinators to ensure that needed referrals were scheduled, and patients could access these additional services.

In addition to engaged leadership, practices consistently described team-based care and the resulting care coordination as critical to the success of practice transformation, and to sustaining practice improvements. Two practices independently called team-based care and care coordination the “secret sauce” to their transformation success, and argued that if nothing else, practices should invest in personnel to develop these building blocks.

Practices noted that moving to team-based care was not trivial and could potentially slow the practice transformation process. Practices also discussed how the three dimensions of engaged leadership could mitigate potential difficulties. They suggested that practices should draw on their culture of improvement to identify and develop optimal team ratios, especially among medical assistants, registered nurses, and care managers, and create a work environment that establishes roles and responsibilities for each team member to operate at the top scope of their license. Once teams are operating efficiently and effectively, then practices need to pay attention to staffing and turnover. Once trained at the highest scope of their licenses, they found medical assistants and registered nurses may leave for promotions as office managers and care managers, respectively, at other local practices.

Continuity of Care and Prompt Access to Care

All practices interviewed offered empaneled continuity of care and worked to provide prompt access to care through multiple service channels, including phone visits, patient portals, group visits, telemedicine, alternative hours, and house calls. As practices strengthened other building blocks, however, barriers to these building blocks arose. Two practices reported that focus on preventative, population medicine and care coordination resulted in greater patient utilization of services. Scheduling prompt follow-up visits became more difficult, and patient wait times increased. This barrier was addressed through improved scheduling, patient flow, and communication. For practices that took those steps, access improved and wait times decreased. Other practices reported that the move to larger team-based models of care created increased cross coverage among team members and decreased continuity of care. They addressed this barrier through improved scheduling and communication among team members about their patients and patient panels.

Joy of Practice

All but one of the practices indicated that their transformation efforts led to increased joy of practice. The one outlier practice indicated increased sense of purpose and mission and did not indicate decrease in joy or well-being, but did acknowledge that increased work necessary for practice transformation moderated increased joy of practice. For all other practices, joy was derived from multiple aspects of the transformation process. One aspect was the correlation between joy and team-based care.

It was the collaborative teamwork that seemed to really be one of the highest indicators of peoples’ satisfaction in the practice … Particularly for complex patients that it’s hard as an individual practitioner to manage complex patients emotionally as well as the actual medical work ... So that turned out to be one of the best parts of, you know, joy in practice.

Joy was correlated to the work structure of teams. In many practices, medical assistants would room patients, ensure all paperwork was printed and complete, and act as scribes entering most of the information into the EHR. This allowed physicians to focus on patients, not the EHR. As one physician stated, “I got to practice medicine again!” Another physician elaborated,

I could be a physician, not an IT specialist. The transformation really significantly decreased that level of paperwork and enabled the clinicians to really focus on the issues that they were better trained to deal with. ... We’ve done satisfaction surveys. ... Its [laughing] improved my well-being.

Finally, joy was correlated with meeting the triple aim. Practice transformation increased the quality of care. Examples included: reduction of hospital admissions by 80%, mitigating the negative impact of racial/ethnic bias in hospice care selection, improving patients’ health care cost savings, and increasing patient satisfaction. With the exception of one outlier practice, meeting these aims increased joy experienced by practices. As one practitioner said,

I think even greater sense of meaning that we’re all working towards the greater good of patient health and well-being, and I think that genuinely energized people, and I think created opportunities where nurses worked much better, perhaps, as teams.

The bright spot practices selected for this project are on a journey of practice transformation and are in various stages of implementing a value-based payment framework. All building blocks were necessary for practice transformation, but several acted as primary drivers that helped accelerate change among the bright spot practices.

Strategy, communication, and a culture of data-driven improvement are key skills and characteristics of engaged leadership that were common to all bright spot practices and fundamental to beginning and sustaining practice transformation. Team-based care and care coordination were identified by some practices as the secret sauce of transformation success. Understanding the importance and challenges attendant with team-based care can direct a practice to make decisions about where to invest time, money, and effort.

Payment was added to the building blocks framework and identified as the foundational driver and barrier of practice transformation. Although practices interviewed were transitioning to value-based care delivery, there was little movement toward value-based care payment. Payment was a driver for value-based payment for all practices, especially the DPC and ACO practices, but a barrier for the FQHC, CPC, CPC+, and FFS practices. Until the payment climate shifts such that practices are reimbursed for the value they provide, most practices included in this study have no plans to move toward increased value-based payments, as practices are not willing to assume the financial risk. That puts continuing and sustaining practice transformation at risk.

In spite of an unproductive payment climate, transformation to value-based care delivery is helping practices meet the triple aim to improve patient outcomes and satisfaction and lower patient costs. This is important because becoming more patient centered within a team-based environment was additionally correlated to increasing joy in practice. This indicates that transformation may help practices meet the quadruple aim (triple aim plus physician well-being): being good by doing good.13

Additional observational research is needed to confirm these findings. Prospective studies of practices beginning practice transformation are needed. Given the central importance of team-based care and care coordination, research is needed to understand the ingredients of the secret sauce of both. It would be useful to examine whether academic practices and the presence of medical students or residents affects this process. In addition, research is needed to examine joy of practice and burnout of the medical assistants and others who have been assigned the challenging task of managing most of the paperwork and EHR data entry.

Family physicians are increasingly making or contemplating the transition to comprehensive, value-based care. Results from this project identified drivers that practices around the United States are deploying today to move transformation forward, and ways to work through potential barriers on the path to transformation. The bright spots practices in this project reinforced the relevance of Bodenheimer’s 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care and its relationship to joy of practice and achieving the triple aim. However, it was also evident that without an adequate payment structure to support the move toward value-based care it was difficult to advance and sustain that transformation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the practices who agreed to participate in this project. They are also thankful for the hard work of all members of the project team including: Jack Janson, Christian Carman, Wyatt Golledge, Larab Ahmed, MD, Alaina Payne, MD, Amanda Shaw, MD, Aaron George, DO, Brad Neaderhiser, PhD, Farhad Modarai, MD, Raymond Tsai, MD, and Kathryn Harmes, MD. Finally, this work would not be possible without the support of the College of Community Health Sciences at the University of Alabama, Venice Family Clinic, CFAR, Inc., and the eight family medicine member organizations that made FMAHealth possible: STFM, AAFP, AAFPF, ABFM, ACOFP, ADFM, AFMRD, and NAPCRG.

The contents of this project were presented at the the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference in May, 2018 in Washington, DC.

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians. 2017 Value-Based Payment Study: AAFP Data Brief. Louisville, KY: Humana, Inc; November, 2017. http://humananews.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Data-Brief2017_Value-Base_FINAL4.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Donahue KE, Newton WP, Lefebvre A, Plescia M. Natural history of practice transformation: development and initial testing of an outcomes-based model. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):212-219. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1497

- Day J, Scammon DL, Kim J, et al. Quality, satisfaction, and financial efficiency associated with elements of primary care practice transformation: preliminary findings. Ann Fam Med. May/June 2013; 11 (Suppl 1): S50-S59.

- Jabbarpour Y, DeMarchis E, Bazemore A, Grundy P. The Impact of Primary Care Practice Transformation on Cost, Quality, and Utilization: A Systematic Review of Research. Washington, DC: The Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative and the Robert Graham Center; July 2017.

- Gill JM, Bagley B. Practice transformation? Opportunities and costs for primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):202-205. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1534

- Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):272-278. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1531

- Family Medicine for America’s Health. Practice Tactic Team. https://fmahealth.org/practice-tactic-team/#1505047641220-931580ff-4436. Accessed June 26, 2018.

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166-171. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1616

- Centers for Medicare and Medicade Services. Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/comprehensive-primary-care-initiative/ Accessed June 26, 2018.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicade Services. Comprehensive Primary Care Plus. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/comprehensive-primary-care-plus. Accessed June 26, 2018.

- Houck S. What Works to Improve Primary Care: Effective Strategies and Case Studies. Boulder, CO: HealthPress Publishing; 2017.

- Glasser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Routledge; 1999.

- Steger MF, Kashdan TB, Oishi S. Being good by doing good: daily eudaimonic activity and well-being. J Res Pers. 2008;42(1):22-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.004

There are no comments for this article.