Background and Objectives: Trainees—medical students and residents—are an important constituency of family medicine. The Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) Workforce Education and Development (WED) Tactic Team attempted to engage trainees in FMAHealth objectives via a nationally accessible leadership development program. We discuss a how-to mechanism to develop similar models, while highlighting areas for improvement.

Methods: The Student and Resident Collaborative recruited a diverse group of trainees to comprise five teams: student choice of family medicine, health policy and advocacy, burnout prevention, medical student education, and workforce diversity. An early-career physician mentored team leaders and a resident served as a liaison between the Collaborative and WED Team. Each team established its own goals and objectives. A total of 36 trainees were involved with the Collaborative for any given time.

Results: Including trainees in a national initiative required special considerations, from recruitment to scheduling. Qualitative feedback indicated trainees valued the leadership development and networking opportunities. The experience could have been improved by clearly defining how trainees could impact the broader FMAHealth agenda. To date, the Collaborative has produced a total of 17 conference presentations and four manuscripts.

Conclusions: Although trainees felt improvement in leadership skills, more robust trainee involvement in FMAHealth core teams would have made the leadership initiative stronger, while simultaneously improving sustainability among family medicine and primary care reform strategies. Nonetheless, the unique structure of the Collaborative facilitated involvement of diverse trainees, and some trainee involvement should be integrated into any future strategic planning.

Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) aimed to examine the challenges and opportunities currently facing the specialty of family medicine.1 The Workforce Education and Development (WED) Tactic Team was charged to: (1) improve the evaluation of family medicine education to meet the standards of the Entrustable Professional Activities; (2) increase student choice of family medicine through multiple strategies, including enhanced resident and faculty mentoring, with emphasis on building a diverse workforce that addresses health disparities; and (3) increase the strength, impact, and prosperity of family medicine departments and residency programs through recruitment, development, and retention of faculty and preceptors.2 Given that these goals are linked to the experience of trainees, the FMAHealth WED Tactic Team (WEDTT) piloted a Student and Resident Collaborative. The purpose of the Collaborative was to (1) aid the WEDTT in achieving their tactic goals, and (2) engage family medicine trainees in leadership development.

The future of family medicine lies in its trainees, and the major achievement of the WEDTT was agreement among organizations to have 25% of allopathic and osteopathic medical students choosing family medicine by 2030.3 Trainee involvement in planning for the future of family medicine is the key to successful engagement in and sustainability of the field. Although numerous national organizations have one to two elected trainee representatives,4,5 a large presence of trainees in national initiatives is uncommon, obscuring the contribution of this important demographic.

Trainee viewpoints are a window into the strengths and weaknesses of the medical education system. Residents provide feedback on family medicine-specific training, while medical students aid in identifying educational weaknesses. As the health care landscape evolves and the role of physicians changes, trainees can speak to both the desires and ambitions of early-career physicians and the current demands of medicine. Additionally, family medicine has higher rates of burnout than other specialties, with younger family physicians experiencing the highest rates in the field.6,7 Thus, determining strategies to promote long-term commitment to the profession is crucial.

Numerous sources acknowledge the need for leadership development among trainees, noting that leadership skills can improve health outcomes.8,9,10 Yet, neither undergraduate nor graduate medical education are consistently designed with formal leadership curricula to prepare trainees for the evolving health care industry.8,9,10,11 If medical education improved trainee leadership, the health care system would benefit from a cadre of physician leaders; however, this requires significant effort and investment that programs may lack. National organizations can provide some of this training, and involving specialty organizations may signal an investment in the trainee and thus increase retention and the robustness of our workforce.

In this paper, we describe the process of creating a national team of trainee representatives and the challenges we faced. We also identify strategies to improve trainee involvement in future strategic planning for a specialty and leadership development among new and training physicians.

Method of Addressing the Charge

In order to provide trainee feedback on what is now known as FMAHealth, approximately 30 students, residents, and early career physicians were invited to meet with various national family medicine stakeholders. These individuals were nominated in 2014 by each of the eight family medicine organizations, prior to the formal launch of FMAHealth.

Once the FMAHealth structure was created, the WEDTT incorporated trainees by piloting the now-called Student and Resident Collaborative. Initially, the WEDTT leader contacted previously involved representatives and trainees in national leadership positions. This workgroup brainstormed and generated an original collaborative model that was presented to approximately 20 trainees in an open forum for feedback at the 2015 American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) National Conference for Students and Residents.

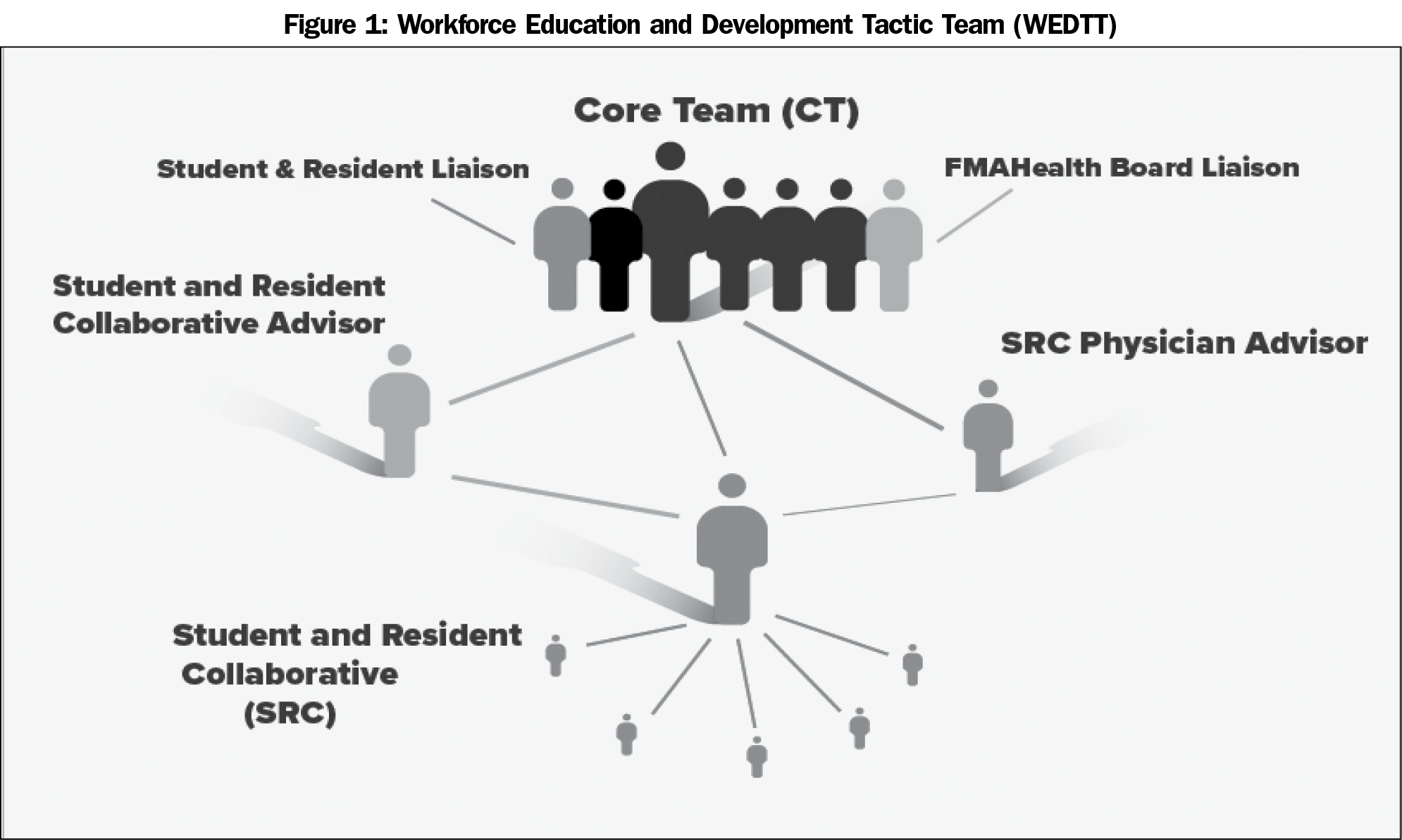

Once the structure of the Collaborative was revised and finalized, medical students and residents were recruited in several ways: a sign-up booth at the 2015 AAFP National Conference for Students and Residents, a general call for involvement via listserv emails, and direct contact by the WEDTT Leader. Each family medicine organization used their own listservs to publicize FMAHealth, inviting the medical community, including trainees, to be involved. Individuals contacted directly were targeted due to involvement in national or local family medicine organizations or through connections with FMAHealth board members. Ultimately, the Collaborative welcomed any interested trainee, regardless of prior participation in family medicine leadership positions. Trainees could join at any point throughout the existence of the Collaborative. At the start, 29 trainees were involved. One early-career physician was chosen by the WEDTT leader as a mentor to provide coaching, support, and oversight (Figure 1).

In July of 2015, the WEDTT leader hosted a webinar orientation to discuss FMAHealth’s mission and the goals of the Collaborative with trainees. The orientation itself was relatively unstructured, but included discussion of project team development. Participants then submitted topics of interest from which the WEDTT leader and physician mentor created and divided trainees into five project teams: student choice of family medicine, health policy and advocacy, medical student education, burnout prevention, and workforce diversity.

Initially, each of these five teams had two trainees who were a designated team leader and a team advisor, selected by the same aforementioned individuals based on their application interests. The leaders were to manage their team members via creating goals and objectives, establishing timelines, delegating work, and ensuring progress. The team advisors were intended to be consultants, connecting the work of the individual teams to the broader FMAHealth initiative. Based on trainee feedback, these roles eventually evolved into coleader positions to eliminate the unclear hierarchy.

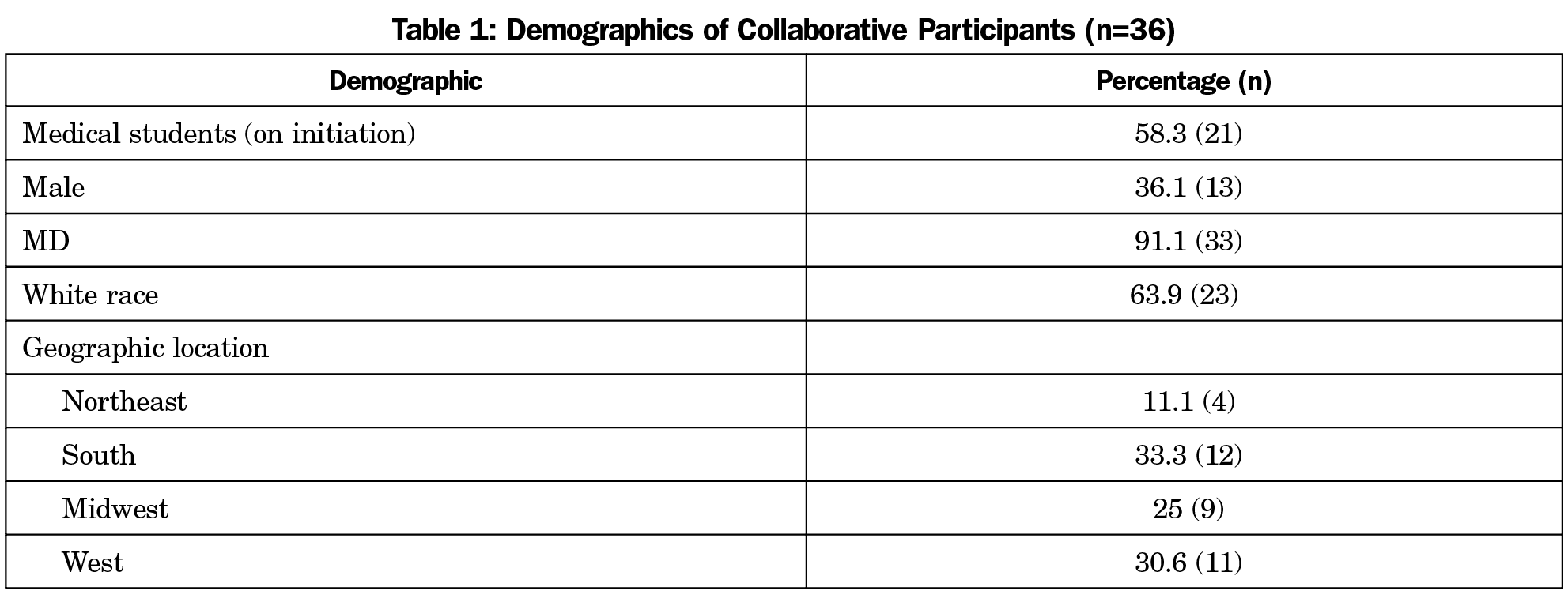

Each team consisted of additional trainee members to help with organization and tasks (Table 1). Led by the coleaders, the teams developed their own goals and objectives. These goals were not necessarily informed by the WEDTT objectives and strategies, but it was assumed that the goals would relate. Each team had a volunteer physician advisor who supported, but did not lead, the team with logistics such as research approval processes, and finding relevant articles or resources outside of FMAHealth. These advisors were chosen by the WEDTT leader after teams had decided upon objectives and did not necessarily have a role within FMAHealth.

To provide the WEDTT with trainee insights, one resident member acted as a liaison between the Collaborative and the WEDTT (Figure 1), with intention to communicate the opinions of the Collaborative on specific WEDTT projects.

To encourage leadership development and reach individual team objectives, multiple approaches were taken. First, the early-career physician hosted monthly evening webinars through a video-based online conference tool for the 10 project coleaders and the WEDTT liaison. These webinars included three components: (1) leadership development, (2) coleader check-ins, and (3) updates from the resident liaison. Leadership development activities included discussions on leadership articles, such as identifying one’s leadership style, conducting effective meetings, or innovation within family medicine. The coleader check-ins allowed teams to share progress, which invited feedback from the group. The liaison check-in updated the Collaborative on the larger WEDTT and asked for insight on specific questions.

Second, each Collaborative team met on their own, typically monthly. Each team determined how to share tasks, recognizing individuals’ schedules. Most teams used multiple communication platforms, allowing trainees to complete work on their own schedules and maintain accountability. To accomplish their objectives, each team utilized various methods, including surveys, focus groups, presentations, research, and establishing external collaborations. The level of interaction with each team’s assigned physician advisor was unique; for some, the advisor was present at monthly meetings, while others consulted the advisor ad hoc.

Finally, teams engaged in ad hoc meetings with the early-career physician who provided consulting and coaching, while allowing independence of the actual problem solving. These meetings were done to structure goals or with teams who wanted additional guidance.

Throughout the timeline of the Collaborative, teams developed new projects and trajectories based on workload, the interest of team members, evolution of leadership, or identified need (subjective or objective). The number of team members fluctuated, with members both leaving and joining; a total of 12 members were involved for the entire duration and 24 additional members were involved at any point. Sixteen additional individuals were associated with the Collaborative through leadership positions within collaborative workforce diversity organizations (eg, Latino Student Medical Association, Gay and Lesbian Student Medical Association).

All positions were voluntary and involved no costs. The online communication platform did have a monthly fee, but was also used by the broader FMAHealth teams and no costs were passed down to trainees. Minimal financial support was given toward survey fees and conference costs.

Given the unique recruitment process, the Collaborative consisted of diverse participants, both in terms of experience, geography, and ethnicity (Table 1). Unfortunately, there was minimal representation from the osteopathic community, with only three of 33 members. Outcomes for the Collaborative focused on three domains: (1) leadership development, (2) tangible outputs (ie, presentations, publications, etc), and (3) overall impact on the WEDTT objectives.

There was no formal pre- and posttesting to measure leadership outcomes. However, participants provided informal feedback through a survey administered 1 year after the end of the Collaborative and through open-ended qualitative feedback throughout the process. The survey response rate was 56% (20/36); multiple emails bounced back from individuals who had graduated from either medical school or residency. On a scale, participants ranked how beneficial involvement in FMAHealth was in regards to their overall future career, to leadership development, and to networking opportunities. The mean response for all questions was 6/10. Regarding satisfaction with the Collaborative and with FMAHealth overall, the mean responses were also 6/10.

Qualitatively, trainees reported improvements in organization, project management, communication, and research. Notably, members felt that their involvement provided valuable relationships with like-minded colleagues and mentors (ie, networking), resilience in their profession, and excitement about improving family medicine.

My work with FMAHealth has expanded my view of what leadership in our specialty can be…There is true benefit and value in working with others who are solely driven by passion and that sharing in that experience can be incredibly rewarding.

I graduated from a medical school that lacked a department in family medicine. FMAHealth provided me with the mentorship I struggled to find locally. My decision to pursue family medicine is continuously validated by our projects in FMAHealth and it makes me excited for the future of primary care.

FMAHealth allowed me to present at the AAFP National Conference...To engage with physicians, residents, and medical students across the nation was a truly valuable experience.

When asked about improvements in the Collaborative structure, multiple participants stated that the initial direction of FMAHealth or the Collaborative was unclear. Clearly-defined roles and objectives were needed—both for individual teams and for how trainees would integrate into broader FMAHealth objectives. Most trainees wanted a more integral role in FMAHealth. One participant suggested having trainees on all core teams; another propositioned a core team solely comprised of students and residents. The need for “less over-burdened” mentors was emphasized. One participant stated that having dedicated mentors (ie, with no other roles) would have improved both integration into FMAHealth and team productivity. Finally, many respondents wanted more meetings, specifically in-person to facilitate networking and meet project timelines. The need for financial support was emphasized for in-person meetings and leadership development activities such as conference presentations; residency continuing medical education funds or medical school scholarships were not sufficient.

Many people were talking about change, but we weren’t producing actionable items.

Choosing something that you are passionate about without a clear vision about how it will fit into the bigger picture [isn’t helpful] …we need a better process.

FMAHealth was a large enterprise with a lot of groups and subgroups. The student and resident sub-groups seemed separate from similar groups with faculty. Perhaps we could integrate these groups better.

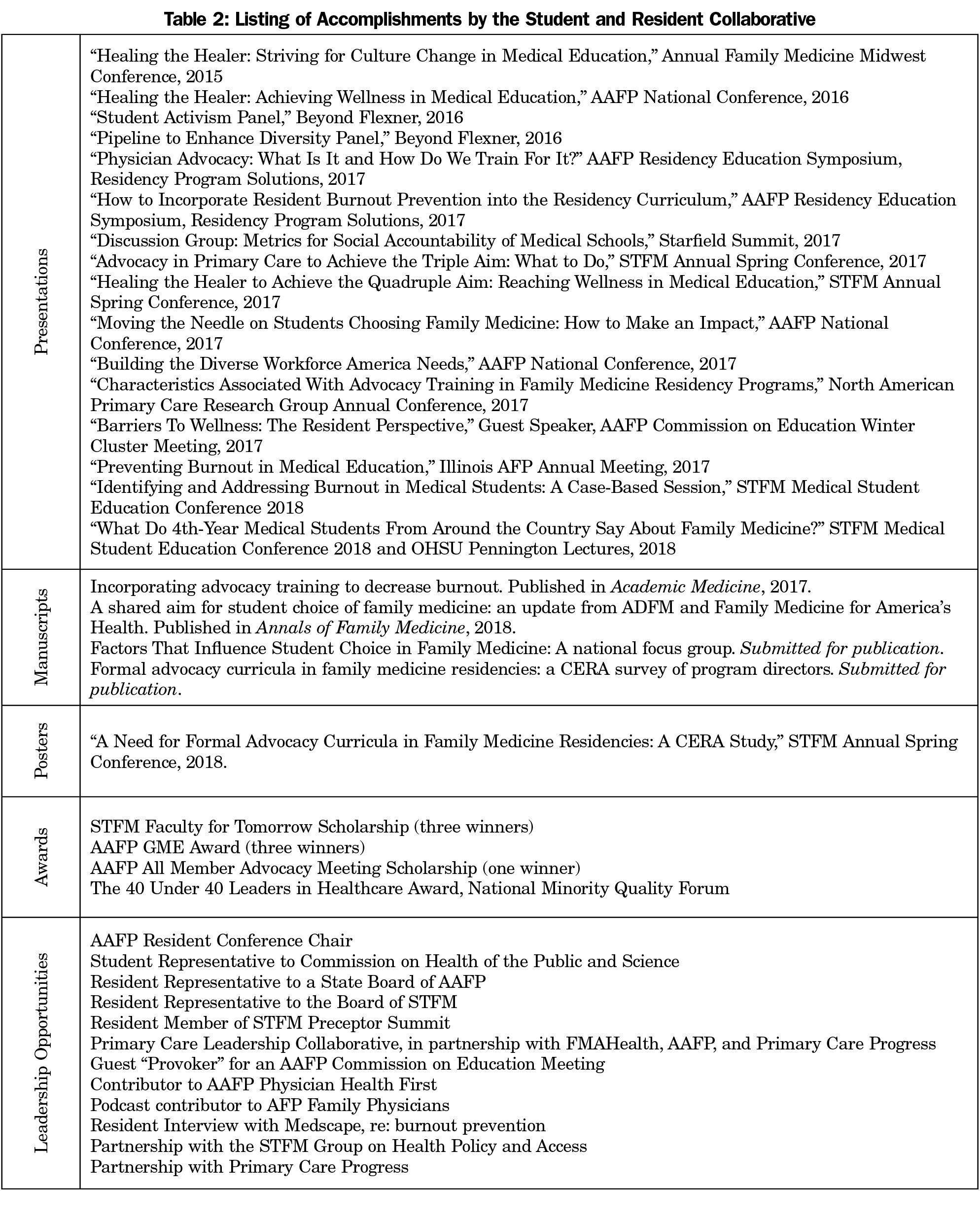

Despite these critiques, the Collaborative provided trainees with opportunities to present at professional conferences, publish in academic journals, sit on committees to contribute opinions, gain advocacy experiences, and develop relationships with colleagues (Table 2). A total of 17 presentations were given, four manuscripts submitted, and numerous additional awards and positions; all included trainees as main contributors, mostly first authors/presenters.

Lessons Learned and Advice for the Future

The Collaborative had two goals: (1) to advise the WEDTT and (2) to engage family medicine trainees in leadership development. By integrating trainees into its structure, FMAHealth had the opportunity to gain insight from, as well as facilitate the development of, family medicine’s next generation of leaders. Although these goals were realized, challenges arose with involving trainees in national organizations. In the following sections, we discuss methods to improve upon our experiences for future initiatives.

Goal #1: Integration With the WEDTT

There were numerous challenges with integrating the Collaborative with WEDTT and FMAHealth. Overall, the Collaborative had minimal interaction with the core FMAHealth teams, including the WEDTT, with the exception of the WED team leader. Although there was a trainee liaison, there was limited bidirectional communication, and the liaison was not included in initial goal development with WEDTT. Additionally, because of residents’ clinical schedules, trainees struggled to attend WEDTT and FMAHealth national meetings. Although the project teams had a physician advisor, this position did not always improve interaction with the WEDTT. Not all physician advisors were members of the WEDTT, and most had limited contact with the team, only interacting with the WEDTT leader.

A. Include Multiple Trainee Representatives on Core Teams and on the Board. This would improve sustainability, engagement, and ownership of the overall strategies, as well as increase diversity of recommendations and reflect the current state of medical training. Ensure these trainees are involved throughout project timelines.

B. Have Clear Objectives to Connect Trainees With the Broader Structure. Collaborative teams were based on trainee interest and coleaders developed any goals desired, which provided engagement in topics individuals were passionate about, but little direction as to how these goals would feed back into the broader FMAHealth structure. Overall, having too much independence led to feelings of nonintegration. Clear, relevant goals should be set and described during orientation to provide structure.

C. Ensure Dedicated Time. Balancing the demands of medical school and residency with outside leadership responsibilities is difficult. No program gave trainees administrative or leadership time to work on projects. There was also no minimum time commitment set by FMAHealth. It is critical for training institutions to (a) recognize leadership involvement as crucial to physician development and (b) provide dedicated time for such involvement.

Goal #2: Trainee Leadership Development

Overall, participants were satisfied with involvement. Yet, because this type of leadership training is rare, comparison of its effectiveness is limited. As an initial model, much of the development was ad hoc and nonuniform; this could be improved in future strategies.

A. Ensure Broad Recruitment. The Collaborative avoided traditional recruitment strategies by not requiring a formal application or election. Through this, the Collaborative improved accessibility, increasing the numbers of involved trainees compared to similar boards, and strengthening the future of family medicine leadership. This process generated improved diversity, a wider breadth of ideas, and provided participants with insight into the challenges and benefits of collaboration. Further work is needed to encourage those who may not seek out opportunities, but have valuable contributions.

B. Create a Clear Structure for Support, Including Financial Support. Trainees were expected to develop their leadership skills by leading a team, but also create a new structure and individual goals. Multiple roles were helpful to leadership development, but required trainees to find a balance between personal leadership development and providing support, guidance, and mentorship to others. Again, clearly defining roles for trainee leaders and for their support structure may help mitigate this. Available staff or a point person for administrative-related questions would help avoid overburdening physician mentors and allow them an integral role in trainee leadership development.

Additionally, if a goal of trainee leadership development is to present at conferences or attend stakeholder meetings, financial support should be set aside or requested from trainee development stakeholders, such as academic family medicine departments or state organization chapters.

C. Emphasize Evaluation.9,10,11,14 The Collaborative was not based in a leadership framework, nor was there rigorous or formal evaluation. Instead, our evaluation relied on feedback through an anonymous survey distributed by the early-career mentor and ongoing informal qualitative feedback. Presentations and manuscripts are both signals of leadership development, but more indicators are necessary. A validated or commonly used assessment of leadership milestones is needed.

Trainee involvement in the WEDTT facilitated leadership development among future family physicians. These trainees now have an improved understanding of advocating for change, program development and management, and establishing team relationships. Future endeavors should continue to facilitate a forum for students and residents to share ideas and collaborate. Including trainees in a structured, integral way would further improve this.

FMAHealth had the potential to include trainees in the strategic planning and execution of a large, national initiative, but the Collaborative’s engagement in the overall WEDTT and FMAHealth structure was cursory and could have been improved. Involving trainees earlier in the process of development, assigning them core positions, or using them as focus group leaders could all strengthen organizational goals. This could improve engagement in the process, increasing the retention, impact, and strength of future family medicine community leaders and academic departments. Using formal evaluations of leadership development can assist in achieving program goals and refining future models. As trainees become family physicians poised to change the health care landscape, family medicine should continue to create a collaborative environment for trainee involvement, emphasizing the culture of family medicine as one that fosters tomorrow’s leaders.

References

- Phillips RL Jr, Pugno PA, Saultz JW, et al. Health is primary: family medicine for America’s health. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(suppl 1):S1-S12. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1699

- Family Medicine for America’s Health. Workforce Education and Development Tactic Team. https://fmahealth.org/workforce-education-development-tactic-team/. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Kelly C, Roett MA, McCrory K, et al. A shared aim for student choice of family medicine: an update from ADFM and Family Medicine for America’s Health. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(1):90-91. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2191

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Leadership development opportunities: residents and students. http://www.stfm.org/CareerDevelopment/FMLeadershipDevelopmentOpportunities/ResidentsandStudents. Accessed July 18, 2018..

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Student & Resident Leadership Opportunities. https://www.aafp.org/membership/involve/lead/students-residents.html. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Medscape. National Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2018. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235#3. Accessed September 17, 2018.

- Puffer JA, Knight HC, O’Neill TRm et al. Prevalence of burnout in board certified family physicians. JABFM. 2017;30:125-126.

- Jardine D, Correa R, Schultz H, et al. The need for a leadership curriculum for residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):307-309. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-07-02-31

- Webb AMB, Tsipis NE, McCellan TR, et al. A frist step toward understanding best practices in leadership training in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1563-70.

- Blumenthal DM, Bernard K, Bohnen J, Bohmer R. Addressing the leadership gap in medicine: residents’ need for systematic leadership development training. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):513-522. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824a0c47

- Hargett CW, Doty JP, Hauck JN, et al. Developing a model for effective leadership in healthcare: a concept mapping approach. J Healthc Leadersh. 2017;9:69-78. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S141664

- National Matching Services, Inc. Summary of Positions Offered and Filled by Program Type. https://natmatch.com/aoairp/stats/2018prgstats.html. Accessed September 17, 2018.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. 2018 Match Results for Family Medicine. https://www.aafp.org/medical-school-residency/program-directors/nrmp.html. Accessed September 17, 2018.

- Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, Bradley EH. Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):656-674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1

There are no comments for this article.