In late 2015, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) was charged with the Family Medicine for America’s Health’s (FMAHealth) Workforce Education and Development Core Team’s task of identifying, developing, and disseminating resources for community preceptors.

SPECIAL ARTICLES

Preceptor Expansion Initiative Takes Multitactic Approach to Addressing Shortage of Clinical Training Sites

Mary Theobald, MBA | Ann Ruttter, MD, MS | Beat Steiner, MD, MPH | Christopher P. Morley, PhD

Fam Med. 2019;51(2):159-165.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.379892

In late 2015, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) was charged with Family Medicine for America’s Health’s (FMAHealth) Workforce Education and Development Core Team’s task of identifying, developing, and disseminating resources for community preceptors.

The charge from FMAHealth came at a time when STFM was discussing strategies to address the critical shortage of clinical training sites for medical students. STFM hosted a summit to identify the most significant reasons for the shortage of community preceptors and shape the priorities, leadership, and investments needed to ensure the ongoing education of the primary care workforce.

Summit participants were asked to propose solutions to achieve the following aims: (1) decrease the percentage of primary care clerkship directors who report difficulty finding clinical preceptor sites, and (2) increase the percentage of students completing clerkships at high-functioning sites.

The outcome of the summit was an action plan with five tactics that are being implemented now:

Tactic 1: Work with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to revise student documentation guidelines.

Tactic 2: Integrate interprofessional/interdisciplinary education into ambulatory primary care settings through integrated clinical clerkships.

Tactic 3: Develop a standardized onboarding process for students and preceptors and integrate students into the work of ambulatory primary care settings in useful and authentic ways.

Tactic 4: Develop educational collaboratives across departments, specialties, professions, and institutions to improve administrative efficiencies for preceptors.

Tactic 5: Promote productivity incentive plans that include teaching and develop a culture of teaching in clinical settings.

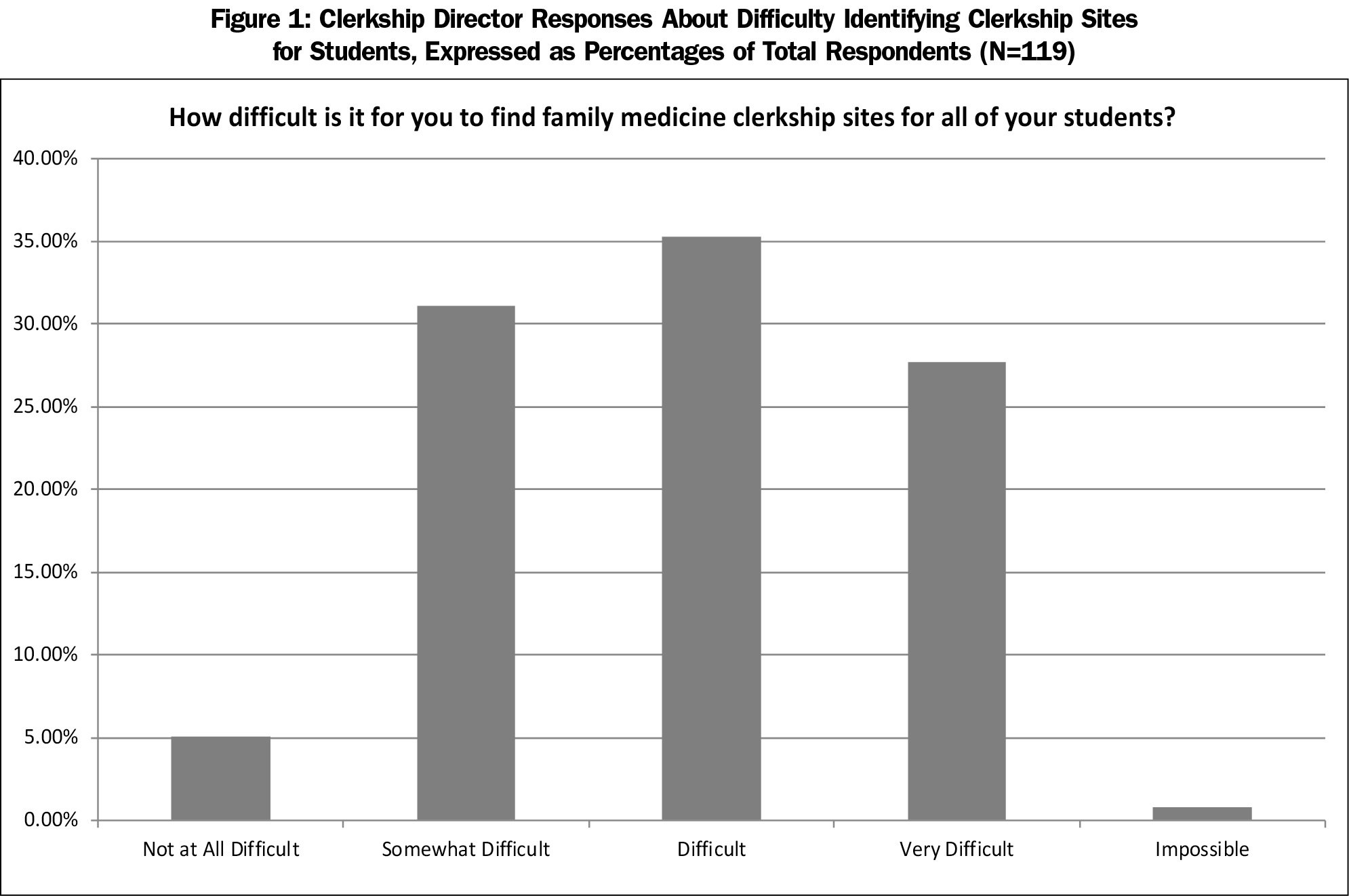

The charge from FMAHealth came at a time when STFM was discussing strategies to address the critical shortage of clinical training sites for medical students. A 2013 survey by the Association of American Medical Colleges found that 47% of allopathic family medicine clerkship directors were having difficulty finding core clinical training sites.1

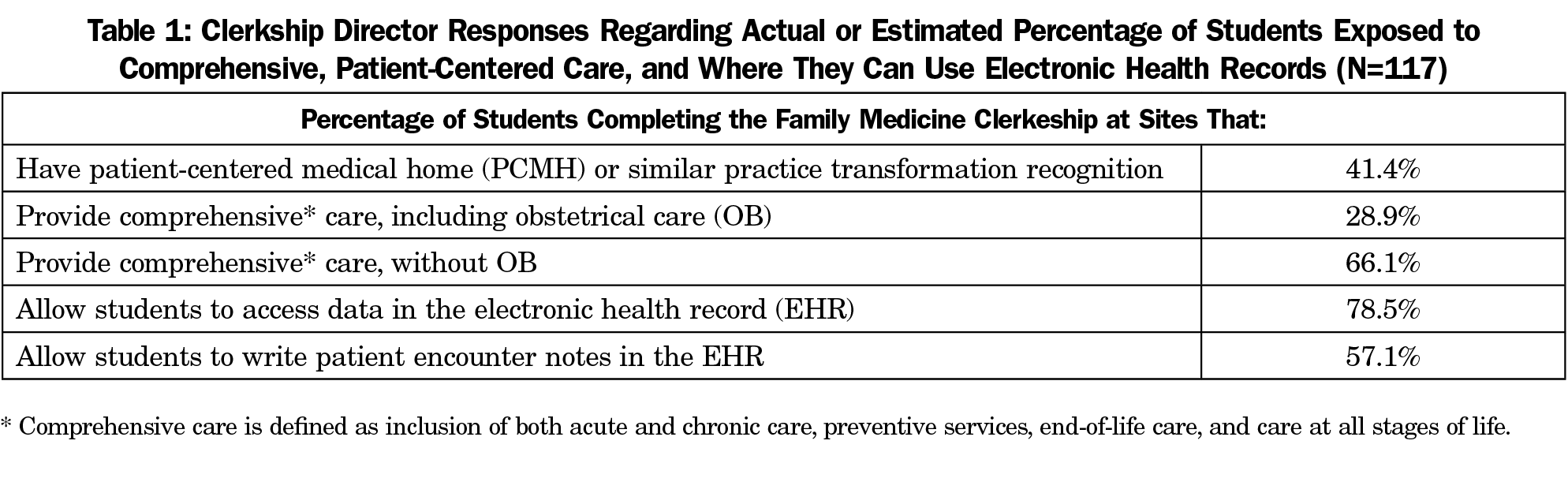

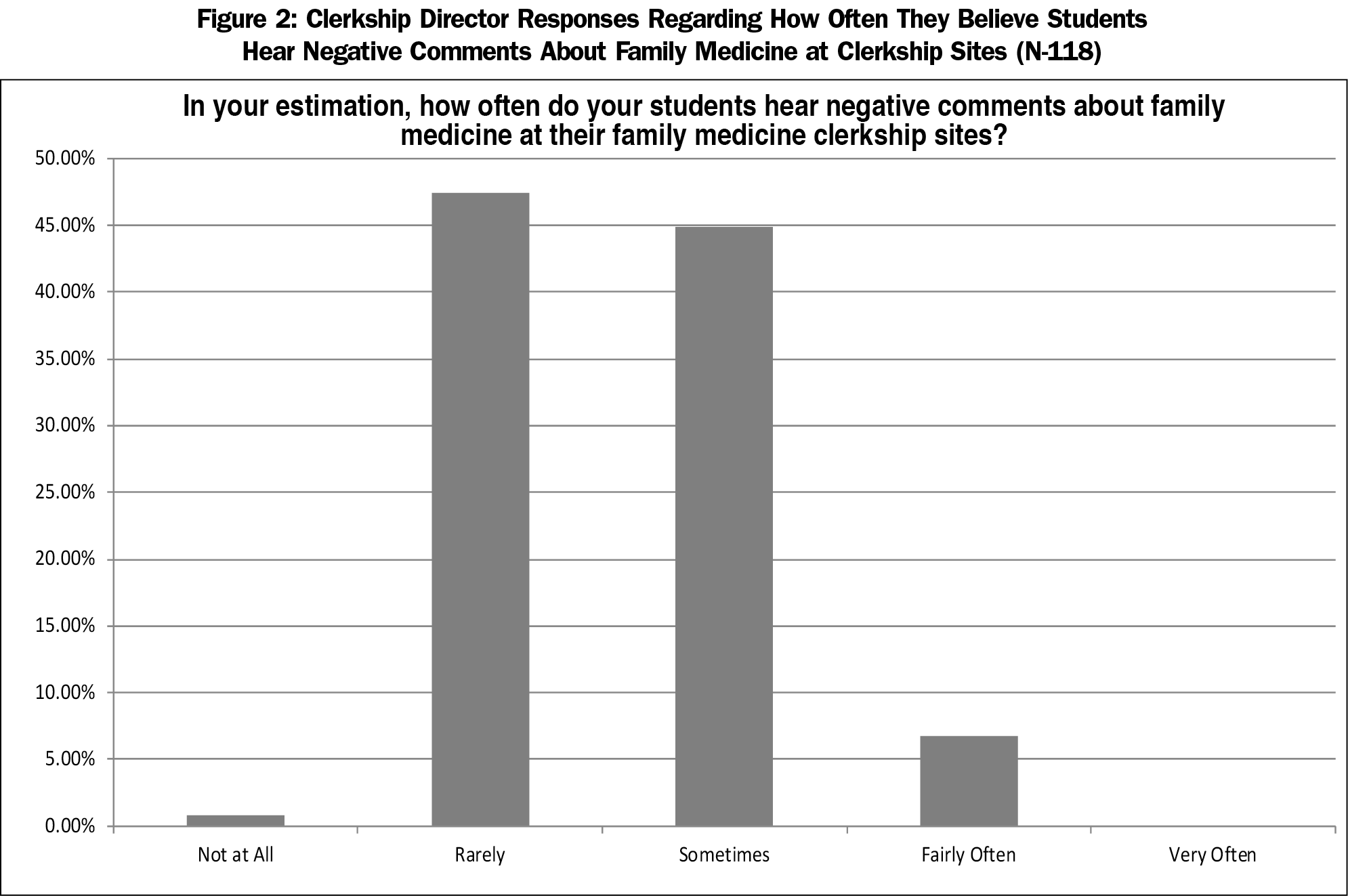

STFM set an aim to decrease the percentage of allopathic family medicine clerkship directors who report difficulty finding clinical preceptor sites from 47% to 35% by 2020. Equally important to finding enough sites was ensuring that family medicine rotations provided high-quality educational experiences. Toward that end, STFM set a goal to increase the percentage of students completing family medicine clerkships at high-functioning sites. While “high-functioning” is based on many factors and is somewhat subjective, for measurement purposes, high-functioning sites were defined as those that didn’t criticize or complain about family medicine as a specialty, offered students an opportunity to experience comprehensive, patient-centered care, and allowed students to document patient visits in electronic health records.

In order to set a baseline for the high-functioning family medicine clerkships, we gathered and analyzed data through the 2016 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors. CAFM is an initiative of four major academic family medicine organizations: STFM, the North American Primary Care Research Group, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine, and the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors.

The CERA survey was emailed to 125 US and 16 Canadian family medicine clerkship directors on August 9, 2016. The survey closed on October 9, 2016. The American Academy of Family Physicians’ Institutional Review Board approved the study. The overall response rate to the CERA survey was 86% (121/141).

The survey confirmed the shortage of family medicine training sites and provided information about the culture and scope of training opportunities at community practices that were training family medicine students (Figure 1, Table 1, Figure 2).

In August 2016, STFM hosted a 1½-day summit to identify the most significant reasons for the shortage of community preceptors and shape the priorities, leadership, and investments needed to ensure the ongoing education of the primary care workforce. The summit was funded by the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Foundation and STFM. Based on a recommendation by the ABFM Foundation, the scope of participants and aims were expanded beyond family medicine, since the preceptor shortage permeates primary care. The 52 summit participants included health system leaders, organizational representatives, policy experts, clerkship directors, clerkship coordinators, community preceptors, physicians who do not precept, and students.

Summit participants were asked to propose solutions to achieve the following aims:

- Decrease the percentage of primary care clerkship directors who report difficulty finding clinical preceptor sites, and

- Increase the percentage of students completing clerkships at high-functioning sites.

During the 1½-day summit, participants identified key solutions that fell into five areas or tactics. The tactics are described below.

The outcome of the summit was an action plan. Through a call for applications, five tactic team leaders were selected to direct the implementation of the plan. Each tactic team leader was assigned a project manager. The tactic team leaders are part of a larger, interdisciplinary, interprofessional Oversight Committee that is charged with:

- Ensuring that work is progressing,

- Ensuring that plans align with project goals and don’t duplicate or interfere with the work of others involved in the plan implementation, and

- Developing solutions to barriers.

The Oversight Committee (chaired by Annie Rutter, MD) includes representatives from STFM, CAFM, Physician Assistant Education Association (PAEA), Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine, American Association of Nurse Practitioners, American Academy of Physician Assistants, and Association of American Medical Colleges, as well as a community preceptor.

Five work teams have developed and begun implementing plans with targeted steps, timelines, and budgets to achieve their goals. Following is a list of tactics with their status as of September 2018.

Tactic 1: Work With the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to Revise Student Documentation Guidelines

The rules regarding the use of student notes for billing purposes have hampered medical education and placed an unnecessary administrative burden on preceptors.2-4 These guidelines limited the student documentation role to review of systems and/or past family and social history and prohibited preceptors from referring to a student’s documentation of other parts of the history, physical exam findings, or decision-making.5 This team was tasked with exploring with CMS and other federal bodies ways to revise student documentation guidelines to relieve unnecessary administrative burdens on preceptors and increase the active learning of students.

Tactic 1 addresses the project aims by increasing the percentage of students who are allowed to document patient visits in the medical record (high-functioning sites), and could potentially increase the number of clinical preceptors (decrease difficulty finding preceptor sites) through a reduction in the administrative burden of precepting.

Status: The Tactic 1 team and others invested in the clinical education of students created a concise request for change. Members of the team then met with CMS in December 2017, providing arguments in favor of a guidelines change and proposing revised transmittal language. At that meeting, CMS requested data to quantify the amount of time this change would save in a clinical visit. The tactic team created an online, anonymous survey, and a link to that survey was distributed through multiple listservs connected with STFM and other organizations and individuals connected to the Preceptor Expansion Initiative. The survey received 1,900 responses in 11 days.

Respondents reported that if CMS allowed the student note (with appropriate teaching physician involvement, supervision, and responsibility) to be used as documentation for billing purposes it would save them administrative time. The bulk (48.3%) said they would save between 31 and 60 minutes per half-day session, and an additional 30% said it would save up to 30 minutes per half-day session. The change would also enable them to spend more time teaching (97% agreed or strongly agreed); 85.3% agreed or strongly agreed they would consider precepting additional students, and 93% agreed or strongly agreed they would enjoy the practice of medicine more. The survey results were sent to CMS on January 24, 2018.

On February 2, CMS released a revised transmittal, Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing Manual, that “allows the teaching physician to verify in the medical record any student documentation of components of E/M services, rather than redocumenting the work.”6

The new CMS transmittal generated compliance questions. An FAQ document, based on correspondence with CMS, is available at https://stfm.org/preceptorexpansion. Additional work is being done by the tactic team to encourage CMS to make the guidelines more inclusive of physician assistants and nurse practitioners, and to provide clarity on documentation guidelines in instances when both residents and students are in a teaching setting.

Tactic 2: Integrate Interprofessional/Interdisciplinary Education Into Ambulatory Primary Care Settings Through Integrated Clinical Clerkships

Clinicians are stretched between the demands of their practices and precepting responsibilities.7 This tactic explores a means to increase the number of learners at a given site without putting more pressure on the clinician’s shoulders. This means transforming education away from the 1:1 preceptor/student model. The team is approaching this by developing simple interprofessional workflow models that demonstrate how multiple learners can learn from and add value to practice and patient care processes. The workflow models will be distributed at national and regional conferences, and the dissemination plan will develop champions that can teach interprofessional education at the local level.

Tactic 2 addresses the project aims by increasing the percentage of students who are learning team-based care (high-functioning sites, as team-based care is a principle of PCMH), and could reduce the number of clinical preceptors needed (decrease difficulty finding preceptor sites) by placing multiple students in one practice.

Status: The team has completed a draft workflow model that will be vetted with faculty and community preceptors. The next step will be to transition the model into resources and training materials.

Tactic 3: Develop a Standardized Onboarding Process for Students and Preceptors and Integrate Students Into the Work of Ambulatory Primary Care Settings in Useful and Authentic Ways

The administrative burden of practicing medicine has become immense8 at the same time that security and legal requirements of teaching (eg, affiliation agreements, immunizations, background checks) have become more stringent and time consuming. This tactic seeks to reduce administrative inefficiencies by standardizing—across departments, specialties, and health professions—the onboarding of students and community preceptors. It also seeks to ensure that students have a consistent level of foundational training before beginning their clerkships, so preceptors know what to expect and can focus on the teaching of clinical and practice skills.

Tactic 3 addresses the project aims by potentially increasing the number of clinical preceptors (decreasing difficulty finding preceptor sites) through a reduction in the administrative burden of precepting and increasing the value of students in the practices.

Status: As a first phase, the team is creating the following for onboarding of students:

- A student passport, which is a fillable document that captures a student’s basic information (address, emergency contact, a color photo, and a brief professional bio), previous training, and verification of malpractice insurance, screenings, and immunizations;

- A “How to Be Awesome in an Ambulatory Clinic Rotation” document to give students tips and strategies to hit the ground running at their clerkship sites; and

- Three online training modules: “How to Create a High-Quality, Billable Note,” “How to Perform Medication Reconciliations,” and “Motivational Interviewing.”

For preceptor onboarding, the team is working on:

- A campaign to promote the standardized use of the AAMC Uniform Clinical Training Affiliation Agreement (https://www.aamc.org/members/gsa/343592/uniformaffiliationagreement.html);

- A faculty appointment onboarding process where administrative personnel at the school/department assist new preceptors in developing and formatting CVs during a phone interview; and

- A collection of best practices and resources for onboarding preceptors (eg, training in giving feedback, completing evaluations, setting expectations with students).

Tactic 4: Develop Educational Collaboratives Across Departments, Specialties, Professions, and Institutions to Improve Administrative Efficiencies for Preceptors

More than 50% of respondents to the 2013 Multidiscipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey rated “administrative elements” as an important or very important challenge in developing new MD/DO clerkship sites.1

This tactic team will conduct three national projects to pilot, evaluate, and disseminate innovative approaches to standardize the onboarding of students and engage community preceptors. Selected family medicine departments, ideally in collaboration with other specialties and professions, will test the materials and processes being developed as part of Tactic 3, as well as recognition and incentive programs being developed as part of Tactic 5.

The sites will: (a) participate in learning communities to share/learn about intervention approaches; (b) provide status reports; (c) disseminate their findings broadly and agree to participate in a multigrantee synthesis report; and (d) conduct standardized pre/postmeasurement to include the impact of the intervention on preceptors’ administrative burden, learning experience for students, and other metrics specific to the interventions.

Tactic 4 addresses the project aims by potentially increasing the number of clinical preceptors (decrease difficulty finding preceptor sites) through a reduction in the administrative burden of precepting, increasing the value of students in practices, and incentivizing teaching.

Status: A call for applications for pilot departments is being developed in concert with the onboarding materials. The Robert Graham Center has been selected to lead the evaluation of the pilot projects.

Tactic 5: Promote Productivity Incentive Plans That Include Teaching and Develop a Culture of Teaching in Clinical Settings

The unifying theme of the tactics under this umbrella is creating the incentives and culture to expand the pool of preceptors. The target for these efforts is the practices and health systems that employ community preceptors. Tactic 5 addresses the project aims by potentially increasing the number of clinical preceptors (decreasing difficulty finding preceptor sites) by incentivizing teaching.

Status: This tactic team worked with ABFM to create a pilot program that allows academic units (Sponsors) to develop and oversee the completion of performance improvement projects that meet the ABFM Family Medicine Certification requirements (formerly called Maintenance of Certification, Part IV). To receive credit, a teaching physician must complete at least 180 1:1 teaching hours and implement an intervention (approved by the Sponsor) to improve the teaching process. The pilot launched on April 2, 2018 with 41 participating academic units. The Precepting Performance Improvement Program—with modifications based on the results of the pilot—will be open to all interested Sponsors in early 2019.

In order to build a business case for teaching, the team is compiling information on incentives for teaching. This list will be made available to preceptors, health systems, and academic institutions. The business case is also being made through presentations, articles, essays, blog posts, and reflective papers advocating for and delineating the benefits of creating cultures and systems that encourage and reward teaching.

The team has also drafted criteria and benefits for a national recognition program for systems and practices that meet quality teaching criteria.

The Preceptor Expansion Initiative is funded by STFM, the ABFM Foundation, and PAEA. FMAHealth is supporting evaluation of the ABFM/STFM Precepting Performance Improvement Program pilot project.

STFM plans to conduct a repeat CERA survey of family medicine clerkship directors to ascertain if the interventions described above have had a meaningful impact on the percentage of family medicine clerkship directors reporting difficulty finding community-based clinical training sites and the number of students completing their family medicine clerkships at high-functioning sites. Other participating organizations may choose to independently evaluate the impact of the project on their specialties and professions.

While the original plan was to measure success by 2020, several of the projects have expanded in scope and won’t be complete by that date. The Oversight Committee may decide to conduct interval evaluations, in addition to the evaluations of individual projects being done within each tactic.

It will be a challenge to measure the success of this initiative. While it is feasible to do a postmeasurement of the percentage of clerkship directors who report difficulty finding clinical preceptor sites, there is no definitive answer as to what would be a successful result. The number of medical schools and medical school enrollment continues to increase,11 as does the number of PA and nurse practitioner students.12,13

The tactics within this project were born out of a summit that convened leaders representing various stakeholders. A component noticeably missing from any tactic is payment for teaching in community settings. There are medical schools that pay their preceptors to teach, but the majority of allopathic medical schools do not pay their community faculty for teaching medical students.9 While payment for teaching was discussed as the action plan was being developed, there wasn’t agreement by participants at the summit that preceptors should be paid (or how much they should be paid) or that it was feasible for all schools to pay preceptors. Even though payment was intentionally left out of the action plan, it is a topic that is frequently brought up by those who are struggling to recruit preceptors. The American Medical Association is addressing resolutions to

pursue legislative and/or regulatory avenues that promote the regulation of the financial compensation which medical schools can provide for clerkship positions in order to facilitate fair competition among medical schools and prevent unnecessary increases in domestically-trained medical student debt.10

Continued collaboration outside of family medicine and outside of medical student education will be imperative for sustained progress. STFM’s partnership with PAEA brought in leadership, perspectives, and funding for this initiative. The Oversight Committee representation from multiple organizations, specialties, and professions allows for diverse perspectives and experiences leading to meaningful change. A necessary next step will be making a case to health systems leaders—who employ an increasing percentage of family physicians—that creating cultures of teaching is both an opportunity to build and train their organizations’ workforces and critical to sustaining the health care system.

Capitalizing on opportunities as they arise will be extremely important. For example, leveraging the fact that the presidential administration was in favor of decreasing administrative burden allowed this group to make headway on the CMS student documentation guidelines.2,14 Future endeavors can consider other seemingly insurmountable obstacles that may be primed for change.

Our work has been driven by a shared belief that the current model of medical education, where health professions are competing for 1:1 clinical training opportunities with volunteer faculty, is not sustainable. Providing high-quality ambulatory clinical experiences to an increasing number of students in a health care system that demands high-volume patient care is going to require creativity and shifts in thinking about how students are educated.

Acknowledgments

This project is being funded by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, the American Board of Family Medicine Foundation, and the Physician Assistant Education Association. Family Medicine for America’s Health is supporting evaluation of the ABFM/STFM Precepting Performance Improvement Program pilot project.

Presentations: Information about this project was presented at:

- STFM 2018 Annual Spring Conference; May 5-9, Washington, DC

- STFM 2018 Medical Student Education Conference; Feb 1-4, Austin, TX

References

- Association of American Medical Colleges, American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, Physician Assistant Education Association, American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Recruiting and Maintaining U.S. Clinical Training Sites: Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/clinical Training Site Survey. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/13-225wcreport2update.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Patients over paperwork. Patients over paperwork newsletter. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/Partnerships/POPSeptember2018Newsletter.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- Hammoud MM, Dalymple JL, Christner JG, et al. Medical student documentation in electronic health records: a collaborative statement from the Alliance for Clinical Education. Teach Learn Med. 2012;24(3):257-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2012.692284

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Position Statement on Medical Student Use of Electronic Health Records.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs-Items/CMS018912.html. Accessed January 7, 2019.

- Department of Health & Human Services C for M and MS. CMS Manual System Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing SUBJECT: E/M Service Documentation Provided by Students (Manual Update). 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/2018Downloads/R4068CP.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- Fazio SB, Chheda S, Hingle S, et al. The challenges of teaching ambulatory internal medicine: faculty recruitment, retention, and development: an AAIM/SGIM position paper. Am J Med. 2017;130(1):105-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.09.004

- Mazzolini C. The 86th annual physician report: why administrative burdens keep physicians away from patients. Med Econ. 2014; 10;91(21)12-13.

- Anthony D, Jerpbak CM, Margo KL, Power DV, Slatt LM, Tarn DM. Do we pay our community preceptors? Results from a CERA clerkship directors’ survey. Fam Med. 2014;46(3):167-173.

- Kirk LM. Proceedings of the 2017 Interim Meeting of the American Medical Association House of Delegates. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/hod/i17-cme-reports.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. U.S. Medical School Enrollment Up 28% Since 2002. https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/enrollment-05252017/. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- Dehn R, Lessard D, Miller AA, et al. Physician Assistant Education Association, By the Numbers. Program Report. 2016;31. https://doi.org/10.17538/PS31.2016

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. AANP - More than 234,000 licensed nurse practitioners in the United States. Press Releases and Announcements. https://www.aanp.org/press-room/press-releases/173-press-room/2017-press-releases/2098-more-than-234-000-licensed-nurse-practitioners-in-the-united-states. Published 2017. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Patients over Paperwork. Patients over Paperwork Newsletter.

- The White House. Presidential Executive Order on Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-executive-order-reducing-regulation-controlling-regulatory-costs/. Published January 30, 2017. Accessed January 7, 2019.

Lead Author

Mary Theobald, MBA

Affiliations: Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, Leawood, KS

Co-Authors

Ann Ruttter, MD, MS - Albany Medical College, Albany, NY

Beat Steiner, MD, MPH - University of North Carolina School of Medicine Family Medicine Residency, Chapel Hill, NC.

Christopher P. Morley, PhD - S.U.N.Y. Upstate Medical University

Corresponding Author

Mary Theobald, MBA

Correspondence: 11400 Tomahawk Creek Pkwy, Suite 240, Leawood, KS 66211, 913-906-6000, ext 5406.

Email: mltheobald@stfm.org

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.