Background and Objectives: Family medicine is continuously advanced by a reinforcing research enterprise. In the United States, each national family medicine organization contributes to the discipline’s research foundations. We sought to map the unique and interorganizational roles of the eight US family medicine professional organizations participating in Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) in supporting family medicine research.

Methods: We interviewed leaders and reviewed supporting materials from organizations participating in FMAHealth. We explored existing activities, capacity, and collaboration. We identified areas of strength and opportunities for growth and synergy with respect to how the family of family medicine nurtures family medicine research.

Results: The FMAHealth organizations support certain aspects of the family medicine research infrastructure. Six domains were identified through this work: showcasing scholarship, communication and dissemination, workforce development, data-driven initiatives, performing primary research, and advocacy for family medicine research. Each organization’s areas of emphasis differ, but we found substantial collaboration on initiatives across organizations, possibly attributable to the fact that many members belong to more than one organization.

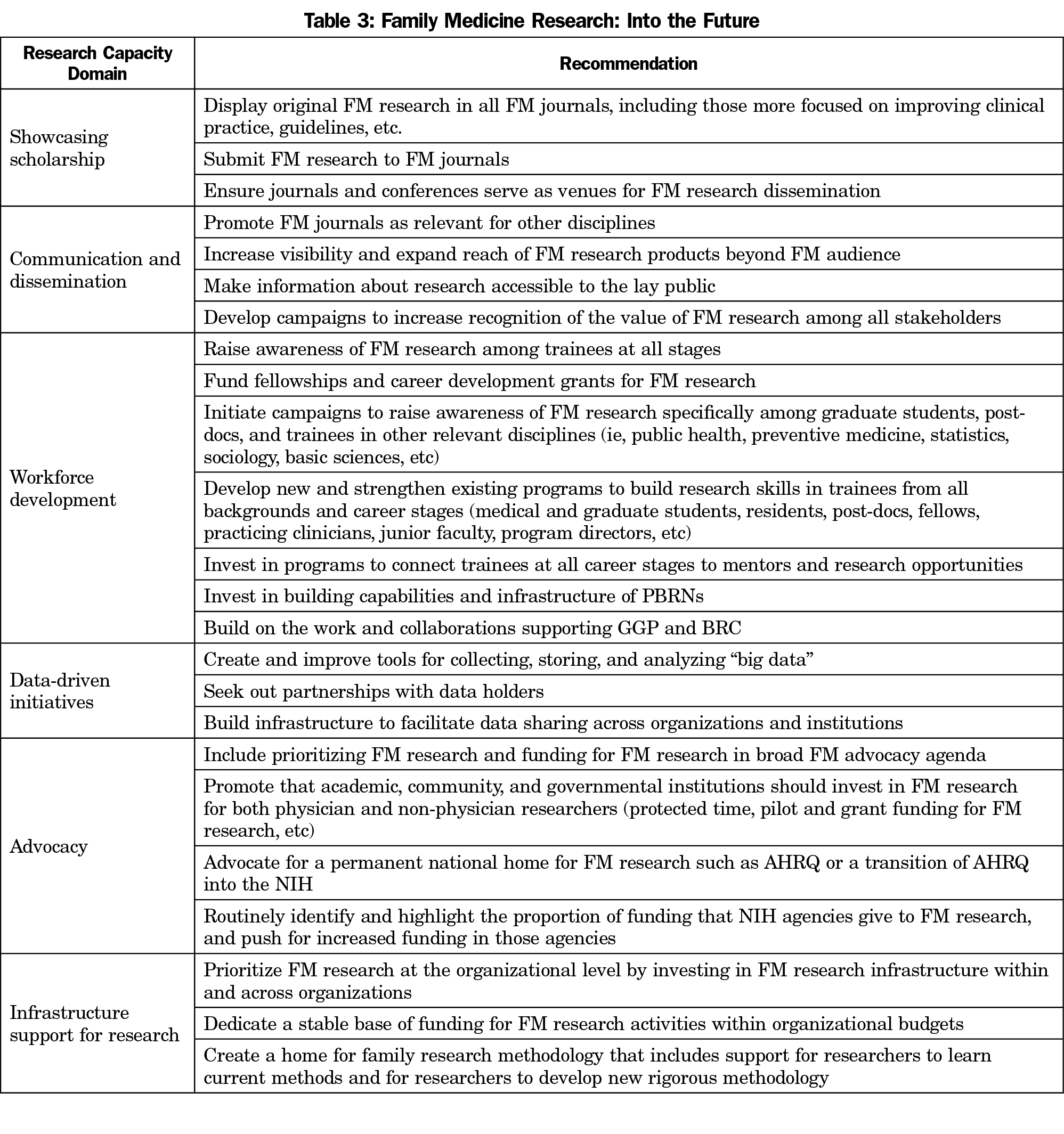

Conclusions: Deliberate contributions to each of the six domains identified herein will be important for the future success of family medicine research. Key opportunity areas described here include coordinated and strategic advocacy for increased funding for family medicine research, dedicated investment in training opportunities, protected effort to grow the next generation of family medicine researchers, pilot funding to build a research base for future high-impact research, and infrastructure to facilitate cross-institutional collaboration and data sharing.

As the United States strives for a more patient-centered and cost-effective health care system, there is critical need for strong primary care built on a robust research foundation.1-3 Family medicine research contributes to that foundation and has expanded in size and breadth over the past several decades. However, the field continues to struggle both to define itself and garner attention from federal funding agencies proportional to its disciplinary peers.4-7 Ongoing research is vital to advance the specialty of family medicine, to solve important problems relevant to family medicine, health care systems, and population health, and to improve care delivery and patient outcomes.

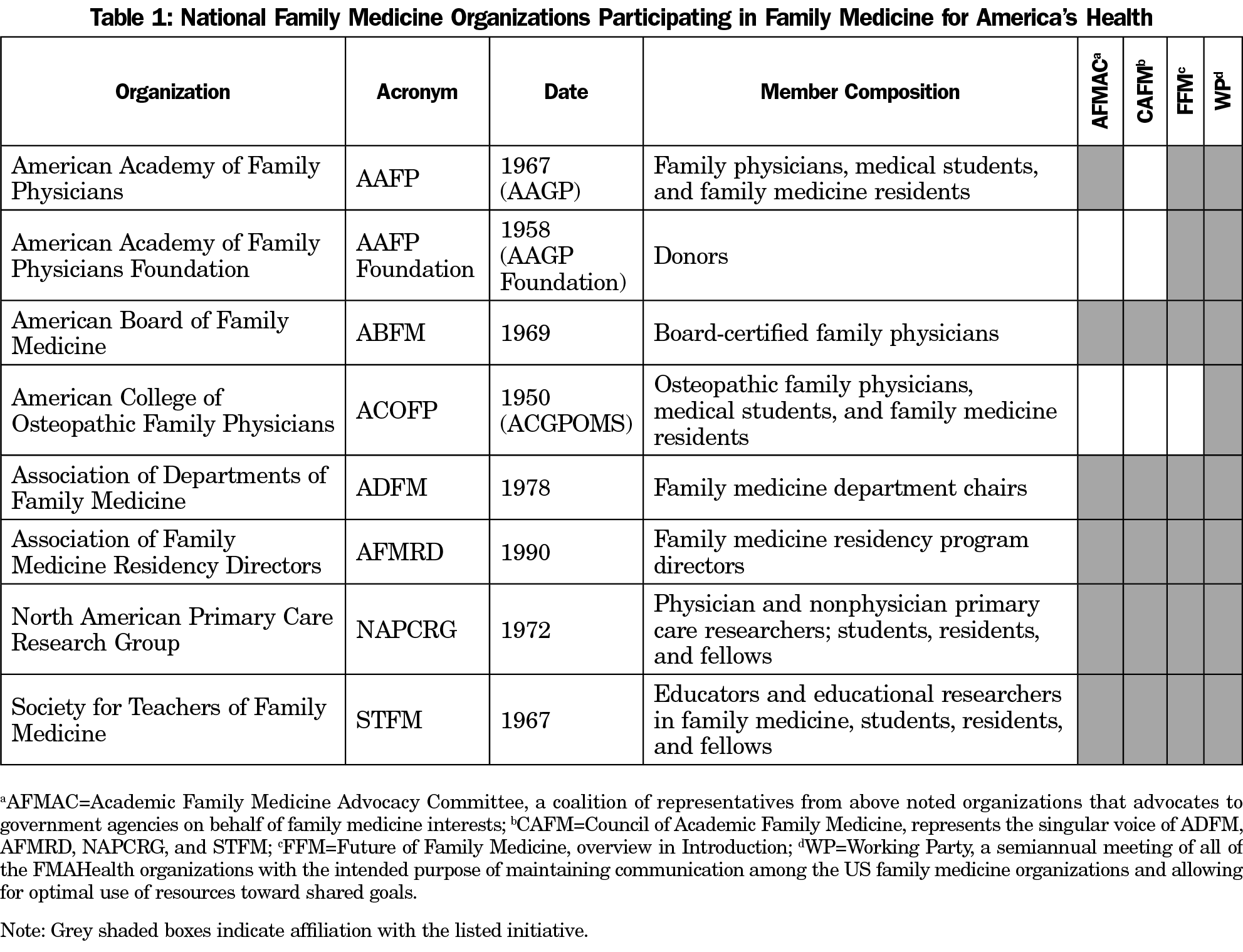

Since the inception of family medicine as a discipline in 1967, family medicine leaders have pushed to develop and strengthen a research agenda with adequate infrastructure.8,9 The North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) was formed in 1972 to promote and provide support for family medicine and primary care research.8 In 2002, the Future of Family Medicine (FFM) initiative, sponsored by seven US family medicine organizations (AAFP, AAFP Foundation, ABFM, ADFM, AFMRD, NAPCRG, and STFM; see Table 1), aimed to solidify a strategy for transforming the discipline of family medicine to accommodate the changing needs of patients and health care in the United States.10 From the FFM initiative, three driving themes for family medicine research emerged: (1) a push for practice-based rather than academic health center-based research, (2) an emphasis on research as an integral part of medical education at all stages, and (3) a glimpse into the future of informatics and big data, especially regarding quality improvement and chronic disease registries. In the nearly two decades since FFM, family medicine research has grown in these three key areas and beyond, with the leading national family medicine organizations taking on varying degrees of responsibility to support family medicine research.

To date, no studies have comprehensively catalogued and mapped the roles that family medicine’s national organizations play in support of family medicine research. In 2013, the seven family medicine organizations from FFM, with the addition of the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians (ACOFP), launched a new project, Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth).11 FMAHealth built on the FFM project with a “new commitment…to strategically align work to improve practice models, payment, technology, workforce and education, and research to support the Triple Aim.”12,13 In the work reported here, the FMAHealth Research Tactic Team identified and described the infrastructure, resources, and overall research capacity supported by the FMAHealth organizations, including strengths, synergy, and future opportunities for the organizations to bolster the family medicine research enterprise.

Primary data was collected in this qualitative descriptive study through semistructured interviews. Key informants were leaders of the FMA Health organizations who could address organizational roles and efforts in support of family medicine research. Key informant candidates were identified based on their leadership positions within the eight FMAHealth organizations, likelihood of being familiar with research-related initiatives within their organization, and willingness to be interviewed. Informants were invited by email to participate in a 1-hour semistructured interview. The interview guide (34 questions and probes across domains; available upon request) addressed five domains of the informant’s organization: (1) capacity for undertaking or supporting research endeavors, (2) communication and dissemination of research, (3) organizational planning, (4) research priorities, and (5) global contextual considerations. Thirteen key informants were interviewed in person or by phone between August 2017 and April 2018. The interviewer took detailed notes during each interview, but interviews were not recorded. The same investigator (C.M.H.) conducted all interviews. Each informant also provided the interviewer with documents describing specific initiatives and strategic plans from their organization. These documents, as well as the Research Tactic Team members’ personal knowledge of the organizations, supplemented the information provided in the interviews. The AAFP Institutional Review Board approved this study (Study #17-298).

Analysis

A grounded hermeneutic approach guided the analysis.14 Two independent coders (C.M.H., V.J.) reviewed and coded the notes from all interviews. Codes and categories were identified and informed the development of themes that arose from the interviews. After initial coding of the interview notes, the themes, codes, and categories identified by the coders were brought to the FMAHealth Research Tactic Team (A.B., J.K.C., J.E.D., G.B.E., W.P.D., C.M.H., V.J., A.K., W.L., R.N., T.V.) for further refinement and contextual interpretation. Themes were refined over a series of meetings and through member checking with key informants until the group reached consensus on the final set of overarching themes. Information from documents and sources other than interview notes was also reviewed and evaluated for cataloguing activities and initiatives.

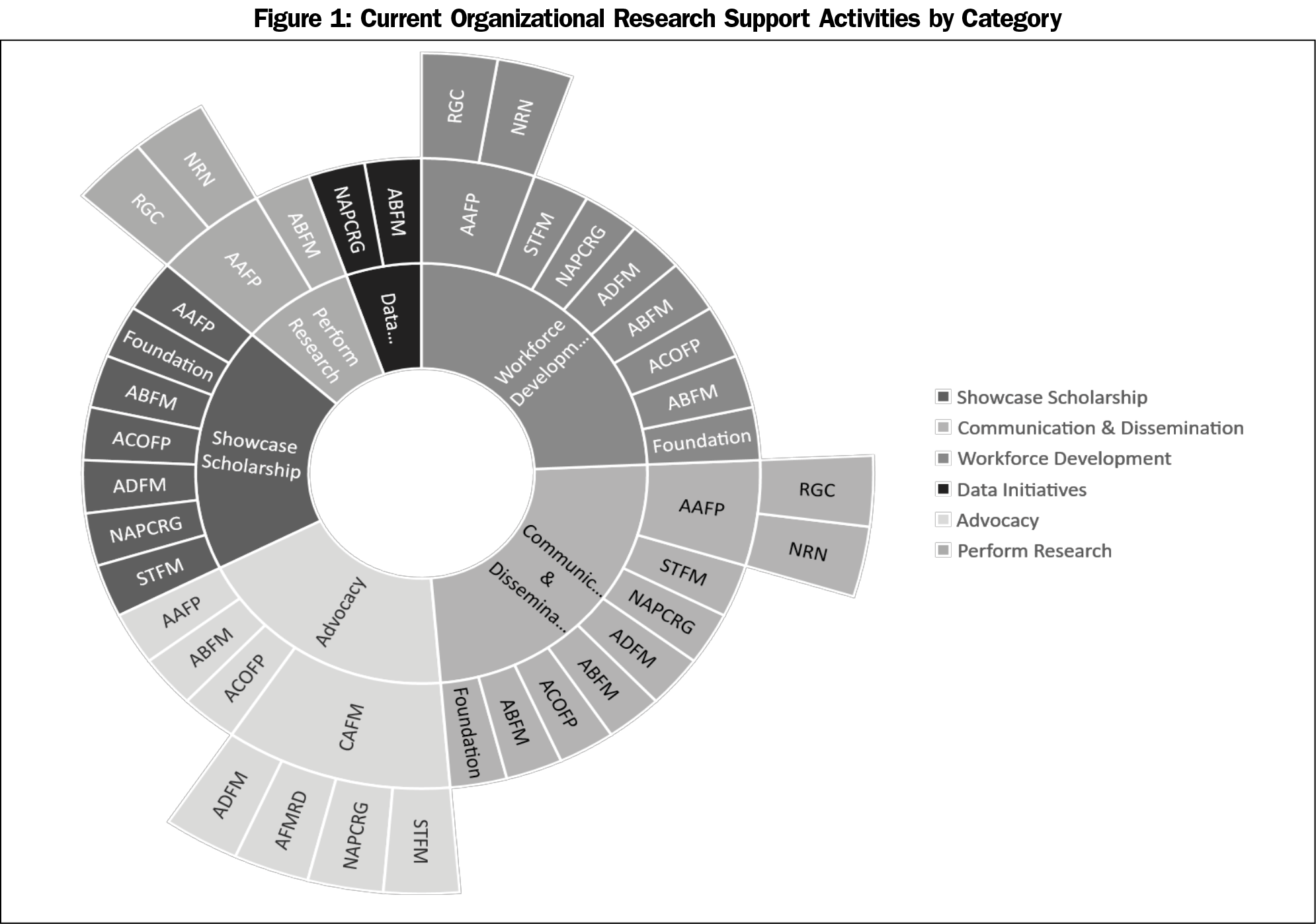

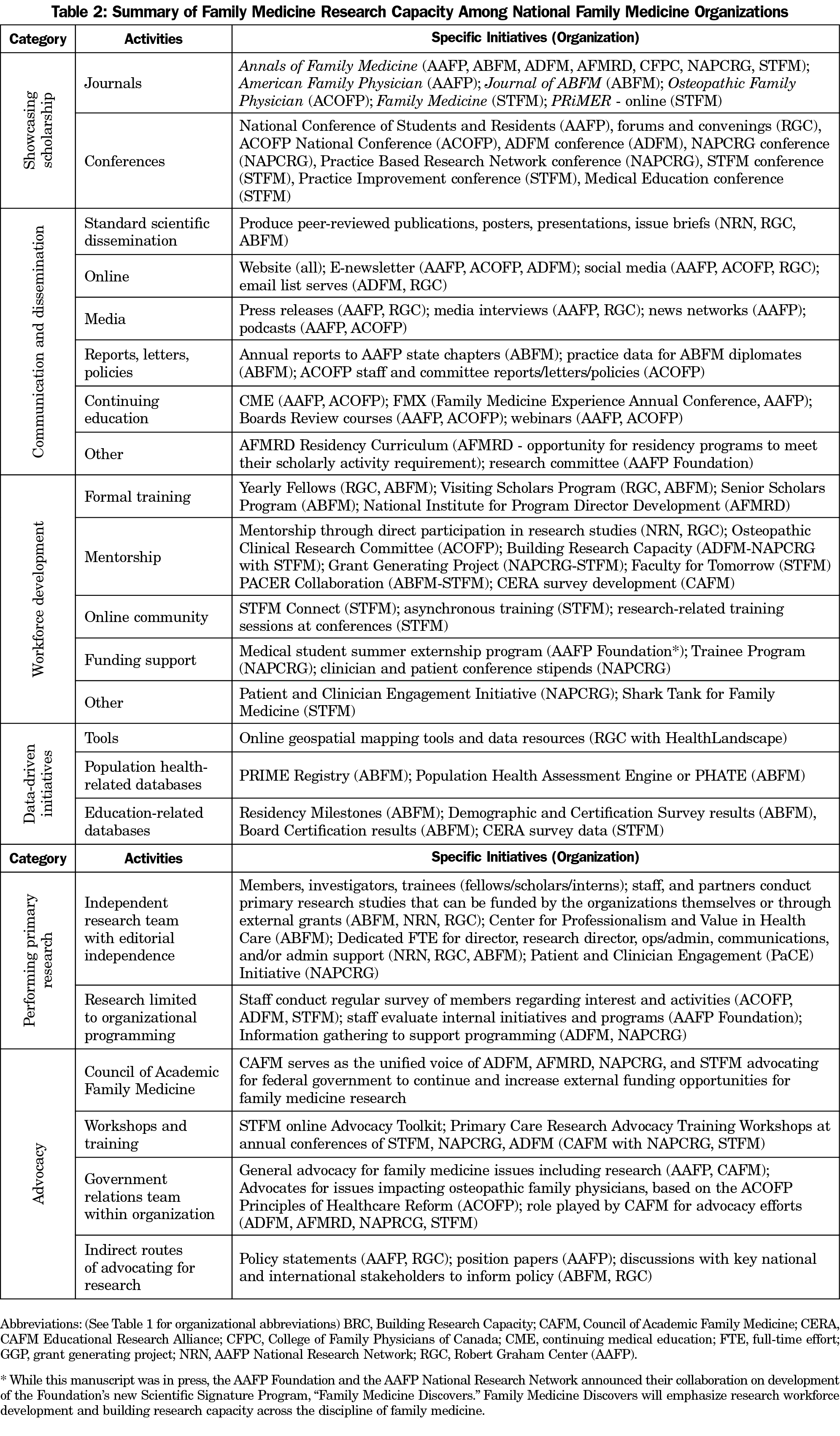

The themes identified during this investigation were the following, and are described in more detail below: showcasing scholarship, disseminating new knowledge, workforce development, support for data-driven initiatives, advocacy for family medicine research, and infrastructure for original research (Figure 1, Table 2). These themes have been addressed below as they relate to family medicine research priorities; current organizational activities; and challenges, gaps, and opportunities for the future. As this study was intended to be a mapping exercise, and the key informant community is very small, participant quotes are omitted to protect confidentiality.

I. Reported Family Medicine Research Priorities

There was strong agreement that family medicine research is uniquely poised to address whole-person care, family- and community-centered perspectives, health across the lifespan, and population health. Most key informants also held that family medicine research should address the clinical needs of both practitioners and patients and support the quadruple aim,15 and that research on reducing clinician burnout is critical. There was also strong sentiment that family medicine research should be undertaken with the family physician in mind and with the goal of ensuring that clinical needs drive research.

Practice-based research and reinforcing the infrastructure for practice-based research networks (PBRNs) were reported to be critical for undertaking family medicine research in the real-world setting. Key informants expressed that research undertaken in family medicine or other primary care clinical settings exposes limitations to protocols early on, provides information about what happens with complex patients, and reveals problems with integration into clinical flow.

Finally, health information technology and big data were raised as priority areas for family medicine research to make a difference in population health and to reduce administrative burden for physicians and other practitioners. The development of data registries and repositories was recognized to allow for exploration of population level trends and complex retrospective and longitudinal natural experiments that have not previously been possible.

II. Current Organizational Activities

Activities of each organization that support research are listed in Table 2 and displayed by theme in Figure 1.

Showcasing Scholarship, Disseminating New Knowledge, and Workforce Development. Of all organizational activities supporting research, the most frequently described were those efforts to create opportunities to showcase scholarship. Organizations sponsor an array of peer-reviewed journals and conferences as venues dedicated to original research. In addition, organizations communicate and disseminate new knowledge through issue briefs, reports, letters, policy statements, social media, and other means. Finally, several initiatives develop the research workforce through structured training programs (fellowships, conference sessions), mentorship opportunities, online communities, and funding support for students, residents, and midcareer researchers.

Support for Data-Driven Initiatives, Research Infrastructure, and Performing Original Research. Many interviewees mentioned that having an organized infrastructure for gathering and storing large datasets is essential for primary care researchers to respond to new questions that arise in a rapidly changing health care landscape. ABFM and the Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM, see Table 1 for organizations composing CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) support initiatives and infrastructure for gathering and storing large datasets. The CERA survey gathers data from important family medicine workforce stakeholders and provides mentorship and education for junior researchers throughout the process. ABFM launched its PRIME registry in 2017, a population health and performance improvement tool that extracts patient data from the electronic health record and turns it into actionable measures for clinicians and practices, and the Population Health Assessment Engine (PHATE), will map electronic health record data and overlay community metrics.

The AAFP and ABFM house dedicated leadership, staff, and trainees who perform original research. These teams pursue independent grant funding to support a large portion of their operational costs. The AAFP currently houses two research centers, the Robert Graham Health Policy Center (RGC) and the National Research Network (NRN), in addition to the HealthLandscape innovation program. NRN and RGC conduct research intended to inform and impact clinical practice, population and public health, payment and measurement, health information technology, and health policy. Similarly, ABFM, has a research team focusing on medical education research topics (eg, ACGME requirements, value of certification programs, graduate career paths), as well as projects relating to clinical practice, population health, and alternative payment models.

Advocacy and the Voice of Family Medicine. Interviewees emphasized the increasing importance of advocacy for family medicine research and the unified voice of family medicine; however, few examples were given regarding successful outcomes that have resulted from specific advocacy efforts. Over the last decade, family medicine research advocacy has centered around increasing funding and creating a stable home for primary care research at the national level. These advocacy efforts are mainly led by CAFM, with a lobbyist on staff representing the unified voice of ADFM, AFMRD, NAPCRG, and STFM. STFM has created an online advocacy training toolkit for their members and stakeholders and has partnered with NAPCRG to offer in-person training at both organizations’ conferences. While the family medicine community has successfully partnered with others in advocating for continued funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), AHRQ’s overall funding is stagnant, and there is still no designated funding stream for the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research, currently housed at AHRQ. The AAFP and ACOFP each have their own government relations staff to advocate on a broad range of issues impacting family physicians. In addition to direct lobbying efforts, AAFP and ABFM also publish policy statements and position papers on various issues and participate in discussions with key national and international stakeholders to inform policy changes.

III. Challenges, Gaps, and Opportunities for the Future

Interviewees from all of the organizations noted short- and long-term goals for expanding the capacity both individually and collectively to strengthen the family medicine research enterprise.

Showcasing Scholarship, Disseminating New Knowledge, and Workforce Development. All leaders cited a need to improve communication and dissemination of the important work done by family medicine researchers to the lay media, public and political officials, and local communities. Raising the visibility of family medicine scholarship to a broader audience was reported as important for building legitimacy and expanding support for family medicine research as an academic endeavor with real-world impact.

Several interviewees also emphasized the continued need for workforce development and that expanded fellowship opportunities and other programs supporting research across the career continuum were needed. Sustainability of successful pilot initiatives was noted as an ongoing challenge, particularly with respect to funding and limited staffing within individual organizations.

Support for Data-Driven Initiatives, Research Infrastructure and Performing Original Research. Beyond the research units of ABFM and AAFP, family medicine organizations view their roles in building FM research capacity and infrastructure more as providing support for their members rather than directly contributing to original research studies. For example, several key informants noted that their organization wanted to expand efforts to develop a sustainable infrastructure that organizes and stores large datasets. Cross-organizational efforts are ongoing to track and catalogue family research activities longitudinally, and ADFM is leading efforts to create a tracking system for academic research and a core dataset of standardized measures to be used by family medicine departments over time.

Advocacy and the Voice of Family Medicine. Several leaders noted the lack of prominent advocacy for family medicine research beyond work done by CAFM. These key informants highlighted that research advocacy is not always seen as a high priority among the largest family medicine organizations who primarily focus their advocacy efforts on practice and payment policies. Because family medicine research is not prioritized by the organizations with the most robust advocacy programs, those interviewed pointed toward a general need for more interorganizational leadership that values research and knowledge generation as organizational priorities. On a local level and in the academic world, several highlighted the need to help family medicine researchers advocate for increased research support from their home institutions with tangible investments such as pilot funding, protected faculty time, or sustained investment in research infrastructure (eg, community laboratories, practice-based research networks).

Over the past few decades, family medicine organizations have continuously enhanced their contributions to a growing family medicine research enterprise. Although each family medicine organization has its own mission and serves a unique membership, they all value research as a crucial aspect of family medicine, both for maturation as an academic discipline and for advances toward achieving the quadruple aim.

The leaders interviewed for this work agreed that family medicine research should advance care delivery and patient outcomes and should be carried out where care is delivered as much as possible (ie, in PBRNs). High value was placed upon research workforce development as well as communicating research findings to reach broad audiences, and the activities of the organizations reflect these priorities (Figure 1). The importance of family medicine research advocacy arose as a global contextual consideration in the interviews, with a recognition that family medicine generally has a robust advocacy agenda, but specific family medicine research advocacy efforts were concentrated within the academic organizations represented by CAFM. It was also evident that the family medicine organizations not represented by CAFM and with substantial resources dedicated to general family medicine advocacy (with minimal emphasis on advocacy for research) often need to rely on the findings from relevant research in furthering their advocacy priorities. Thus, increased advocacy for family medicine research will indirectly benefit these other efforts. Importantly, many of the respondents acknowledged the need for the organizations to work toward finding areas of synergy in the future and to build collaborations with one another to more efficiently use their limited funding and staff to support family medicine research.

Findings here indicate that, as organizations continue to build their own research capacities in the various categories of activities of workforce development, advocacy, supporting data-driven initiatives, etc, all are open to finding new ways to collaborate and utilize one another as partners and advisors. Collaboration among individuals is already prevalent, as many individuals are members of multiple organizations; however, the impact multiple membership has on real organizational collaboration is not quantifiable from this work. The AAFP and ABFM frequently collaborate and share ideas for research projects. Nearly all NAPCRG initiatives for workforce development (ie, the Grant Generating Project, [GGP], and Building Research Capacity [BRC]) exist in collaboration with other organizations. One of the longest standing collaborative efforts, the Annals of Family Medicine, exemplifies a partnership among seven family medicine organizations that formed when funding collapsed for two previous journals in 2003.8 NRN, STFM, and the AAFP Foundation expressed interest in collaborating with other family medicine organizations on research pipeline activities, tying nicely with the interest of ADFM, AFMRD, and NAPCRG to increase support specifically for their respective memberships. As the organization inheriting the mission and work of the FMAHealth Research Core Team and central connector for family medicine research among the eight organizations, NAPCRG mentioned a need to “develop collaboration with the AAFP Foundation for research trainee support.” The expression of this goal is in line with the Foundation’s current and past work dedicated to workforce development. Current advocacy efforts for family medicine research also arise out of the collaboration of academic organizations through CAFM.

Overall, much of the organizations’ current attention is focused on strengthening the research workforce and broadening the audience for disseminating family medicine work, while new emphasis has been placed on ramping up advocacy, especially with regard to increasing funding support for family medicine and primary care research. Key informants demonstrated a keen awareness of current workforce development activities, interests, limitations among their own and other organizations, and an eagerness to build new resources and programs. To optimize future success, maximize impact, and increase the likelihood of sustainability despite limited resources across organizations, it is imperative that family medicine organizations seek innovative collaboration opportunities, actively engage top research leaders in collective efforts to augment family medicine’s research capacity and infrastructure, and deliberately avoid creating duplicative groups and programs. Opportunities identified during the thematic analysis (Table 3) synthesize the current activities and areas of focus with recommendations resulting from this study and grouped by research capacity domain. Finally, in order to bolster all efforts to reinforce the family medicine research infrastructure, the majority of organizations view raising the visibility and expanding the reach of family medicine research to a broader audience as clear next steps for the discipline.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this mapping project. First, the interviews were not recorded, and the perspective of the interviewer may have influenced note taking. Known or unknown biases of coders and team members involved in analysis may have influenced interpretation of both interview notes and additional information informing this work. The biases and knowledge of the key informants also influence their interview responses and may have led to responses that did not accurately reflect the full scope of capabilities of a given organization to support research and contribute to the family medicine research infrastructure. Because interviews were time limited, some organizational activities were never discussed. Also, these eight organizations, their projects, collaborations, funding sources, and staffing, are dynamic. Thus, this work is a snapshot of the period in which the interviews took place. In the current chaotic funding environment and with the demand for volunteer work from those already overworking in other roles, it is difficult to interpret how key informants’ and team members’ perspectives may be impacted by the current context in which they operate.

Importantly, family medicine research capacity depends on factors far beyond the support provided by the eight organizations involved in FMAHealth. In addition to academic family medicine departments, there are large and small PBRNs that contribute a great deal to enabling research design. Furthermore, much of family medicine research involves interdisciplinary teams that include researchers in disciplines such as public health, epidemiology, sociology, other medical specialties, and health policy, etc. The research capacity of these other fields of study also contributes to the productivity of family medicine.

Summary

In light of limited resources and funding, organizations must look to increase collaboration where synergies exist to expand and strengthen current initiatives and to develop new opportunities in the research arena. The findings and recommendations presented here are expected to catalyze new collaborations and empower organizations to develop independent and unified plans to address the needs and gaps accounted for here and to be expected in the future. Deliberate and strategic action will be critical for the discipline of family medicine and for the achievement of the quadruple aims of health that are the cornerstone of our health care systems.

Finally, each of these organizations has mechanisms in place to respond to member input. Individuals who are members of these organizations can serve in volunteer or elected positions to influence initiatives or can raise issues to the organizational leadership or boards via traditional governance frameworks. Thus, the members of the US family medicine organizations have the power to use their voices to directly influence family medicine research capacity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the key informants who gave their time to be interviewed for this work; the staff of CFAR, including Mal O’Connor, Ashleigh Reeves, and Christian Carman; Cory Lutgen for his help with creation of Figure 1; and Elizabeth Staton for valuable feedback during preparation of the manuscript.

Financial Support: This work was funded by Family Medicine for America’s Health.

References

- Cullison S. Health is primary—right? Family medicine is certainly for America’s health. Fam Med. 2015;47(1):64-65.

- Fani Marvasti F, Stafford RS. From sick care to health care—reengineering prevention into the U.S. system. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(10):889-891. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1206230

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

- Lucan SC, Barg FK, Bazemore AW, Phillips RL Jr. Family medicine, the NIH, and the medical-research roadmap: perspectives from inside the NIH. Fam Med. 2009;41(3):188-196.

- Lucan SC, Bazemore AW, Phillips RL Jr, Xierali I, Petterson SM, Teevan B. Greater family medicine presence at NIH can improve research relevance and reach. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(10):1213.

- Lucan SC, Phillips RL Jr, Bazemore AW. Off the roadmap? Family medicine’s grant funding and committee representation at NIH. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(6):534-542. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.911

- Green LA, Fryer GEJ Jr, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):2021-2025. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200106283442611

- Bowman MA, Lucan SC, Rosenthal TC, Mainous AG III, James PA. Family Medicine Research in the United States From the late 1960s Into the Future. Fam Med. 2017;49(4):289-295.

- Green LA. The research domain of family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 2):S23-S29. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.147

- Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al; Future of Family Medicine Project Leadership Committee. The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S3-S32. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.130

- Family Medicine for America’s Health. 2017; https://fmahealth.org. Accessed March 30, 2018.

- Phillips RL Jr, Pugno PA, Saultz JW, et al. Health is primary: family medicine for America’s health. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(suppl 1):S1-S12. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1699

- Stream G. Family Medicine’s Agenda to Make Health Primary. Fam Med. 2015;47(8):595-597.

- Addison R. A grounded hermeneutic editing approach. In: BF Crabtree WM, ed. Doing qualitative research, second edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999:145-161.

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

There are no comments for this article.