When the Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) Workforce Education and Development Tactic Team (WEDTT) began its work in December 2014, one of its charges from the FMAHealth Board was to increase family physician production to achieve the diverse primary care workforce the United States needs. The WEDTT created a multilevel interfunctional team to work on this priority initiative that included a focus on student, resident, and early-career physician involvement and leadership development. One major outcome was the adoption of a shared aim, known as 25 x 2030. Through a collaboration of the WEDTT and the eight leading family medicine sponsoring organizations, the 25 x 2030 aim is to increase the percentage of US allopathic and osteopathic medical students choosing family medicine from 12% to 25% by the year 2030. The WEDTT developed a package of change ideas based on its theory of what will drive the achievement of 25 x 2030, which led to specific projects completed by the WEDTT and key collaborators. The WEDTT offered recommendations for the future based on its 3-year effort, including policy efforts to improve the social accountability of US medical schools, strategy centered around younger generations’ desires rather than past experiences, active involvement by students and residents, engagement of early-career physicians as role models, focus on simultaneously building and diversifying the family medicine workforce, and security of the scope future family physicians want to practice. The 25 x 2030 initiative, carried forward by the family medicine organizations, will use collective impact to adopt a truly collaborative approach toward achieving this much needed goal for family medicine.

In 2014, the Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) Board created the Workforce and Education Development Tactic Team (WEDTT) as one of six original core groups to achieve FMAHealth’s strategic plan, to demonstrate the true value of primary care and identify necessary changes in the health care system. The WEDTT addressed the following assigned tactics1:

- Improve the evaluation of the full continuum of family medicine education to include and meet the standards of the Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs).2

- Increase medical student choice of family medicine (FM) through multiple strategies, including enhanced resident and faculty mentoring, with a specific emphasis on building a diverse workforce that addresses health disparities.

- Increase the strength, impact, and prosperity of family medicine departments and residency programs through recruitment, development, and retention of faculty and preceptors, and provide support to enhance their value in their communities and their institutions.

The majority of the WEDTT’s work centered on student choice of family medicine, since family physician production is vital to meet the health care needs of patients and communities in the United States.3 Primary care physicians should represent at least 40% of the physician workforce, yet this measure is currently approximately 32% and falling.4 In 2016, only 12% of US allopathic and osteopathic medical school graduates entered an ACGME-accredited family medicine residency program.5 This article focuses on how the WEDTT addressed the charge to sufficiently produce a diverse family medicine workforce.

Method of Addressing the Charge

Structure

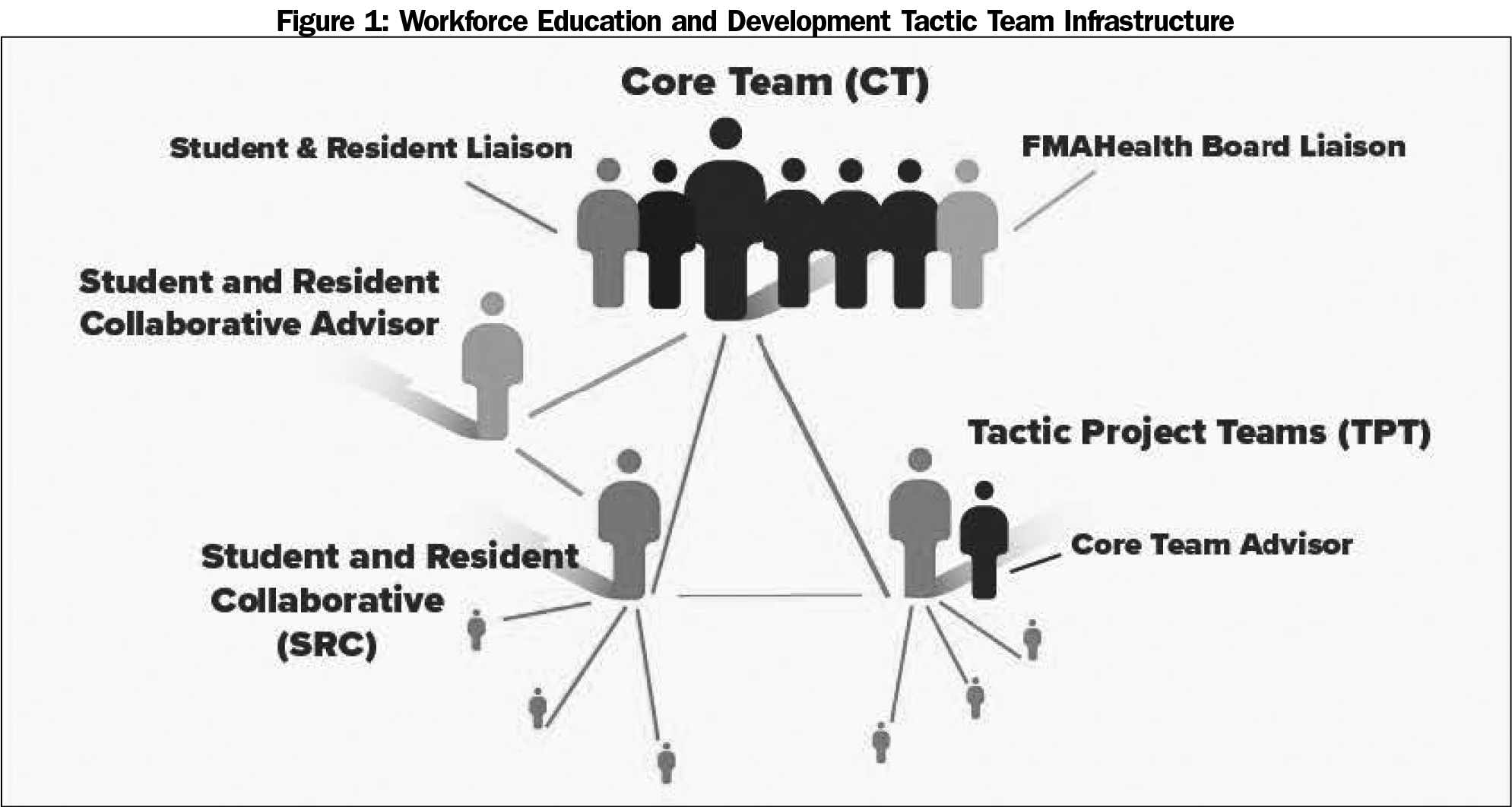

The WEDTT’s infrastructure included a Core Team (CT), five Tactic Project Teams (TPTs), and a Student and Resident Collaborative (SRC) to accomplish its work between December 2014 through December 2017 (Figure 1).

The FMAHealth Board-appointed CT provided macro-level leadership, developed vision and strategy for the team’s work, used outcome-oriented methods to carry out activities, and communicated regularly with other team members.

The TPTs provided micro-level leadership as well as project plan development and implementation. The five TPTs included (1) Education Evaluation and Curriculum Development, (2) Student Choice of Family Medicine, (3) Wellness, (4) Workforce Diversity, and (5) Advocacy, Health Policy and Research. Each team was led by a family physician and had a CT member who acted as an advisor and support for outside organizations and trainees.

The CT created an SRC to utilize medical student and resident viewpoints as a source of inspiration, incorporate trainees’ perspectives into the team’s work, and provide leadership development opportunities for our future workforce. The SRC included five parallel teams and a liaison position on the CT to relay information and viewpoints. SRC teams, led by and comprised of students and residents, were given space to develop projects that fed their passions and related to FM workforce development. An inclusive leadership model was used—any student or resident could participate in the SRC and specific roles were determined by their leadership goals, specific interests, and availability. Over 2 years, approximately 45 students and residents participated in the SRC and contributed to WEDTT work.6 An early-career physician advised and provided professional development for the SRC team leaders.

All teams completed their work through e-mail and videoconference calls, and the CT additionally attended biannual in-person meetings. FMAHealth contracted with CFAR consulting firm to provide project management support for all tactic teams.

Process

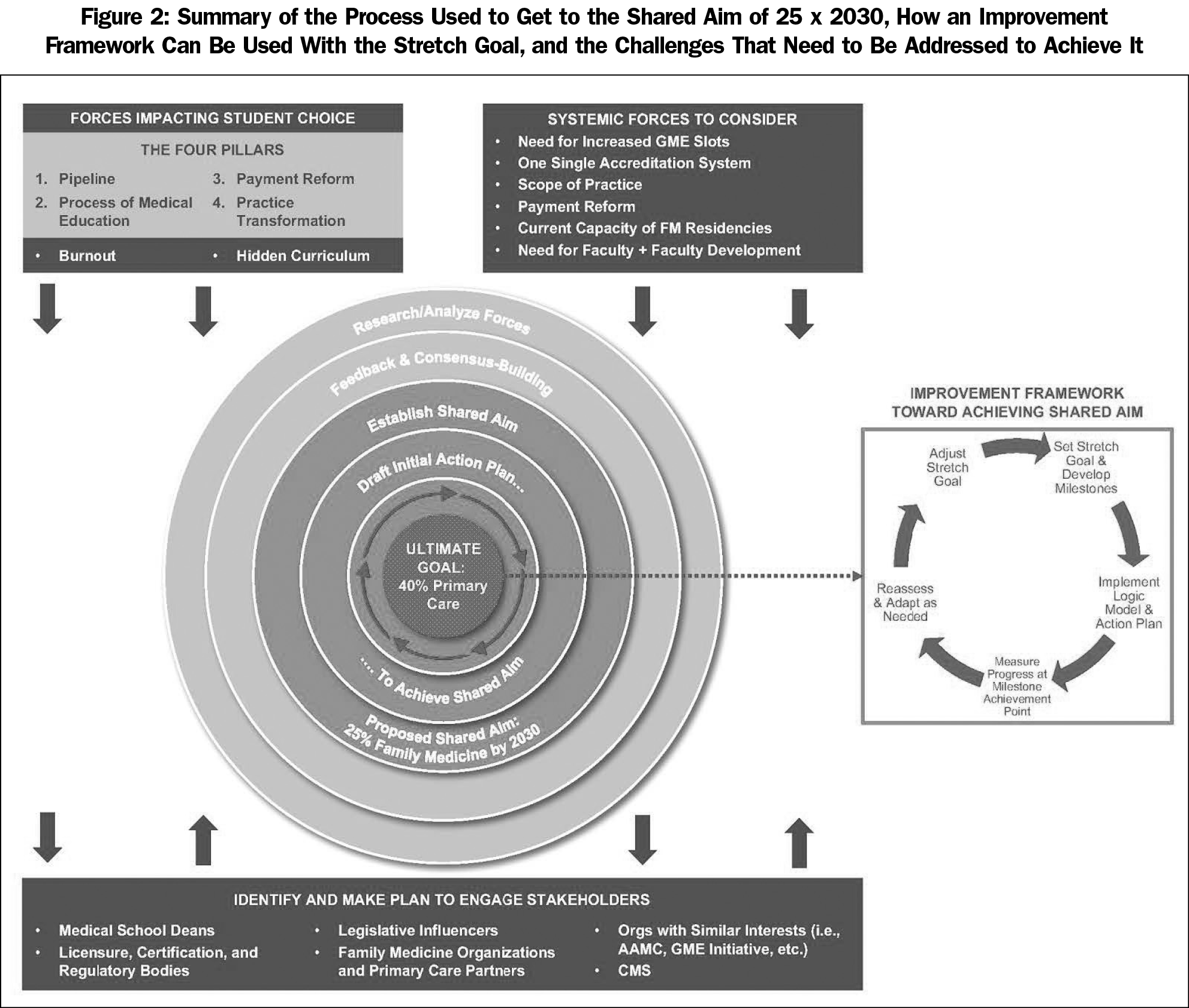

The CT’s strategy to create a work plan included the following key steps: (1) understand current work being done on primary care workforce issues; (2) identify evidence-based areas of impact; and (3) build collaborations with key stakeholders within and outside FM to align efforts, promote inclusion, and develop sustainable solutions. The details of this process are outlined in Table 1.

The WEDTT work effort had originally been planned to span 5 years from December 2014 through 2019. The timeline was accelerated in February 2017 by the family medicine sponsoring organizations (FMSOs) for many of the tactic teams, including the WEDTT, with work to sunset in December 2017. This timeline change shifted the WEDTT’s focus to the most impactful and strategic efforts to increase student choice of FM that could be achieved in the remaining time allotted, rather than completing the entire WEDTT work plan.

A second change included the addition of a CT member. To better understand the priorities, viewpoints, and capabilities of the FMSOs, an organizational staff member was appointed to the CT in January 2016 and funded by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). This member brought a vital perspective to the team’s work and served as a liaison to the FMSOs.

One of the major outcomes of the WEDTT is a shared aim for student choice of family medicine that all FMSO boards agreed to, namely to increase the percentage of US allopathic and osteopathic medical students choosing family medicine from 12% to 25% by 2030 (25 x 2030). The organizations agreed that although the goal is lofty and unattainable without significant reform, it is necessary that the specialty take on this workforce reform to provide the care patients and communities depend on from family physicians. Having a clear, collective aim allows for alignment of current efforts, but more importantly, truly collective and collaborative efforts developed for the future.

There is a need for increased social accountability of US medical schools to produce the workforce to provide adequate health care for the nation.19-22 This requires a strong foundation in primary care.3,7,8 As family physicians provide the majority of primary care throughout the nation, especially in rural and underserved communities, medical schools must produce more family physicians.45 After a literature review of future primary care workforce predictions, factors impacting medical student specialty choice, the culture of diversity and inclusion in medical education, and trends of physician production by specialty at medical institutions (Table 1), the CT proposed a model whereby all FMSOs would share one goal to aspire toward in increasing student choice of FM. With agreement of all eight FMSOs, FM could assertively speak with one consistent voice for one measurable goal, align strategies, and allocate resources to achieve an agreed-upon outcome.

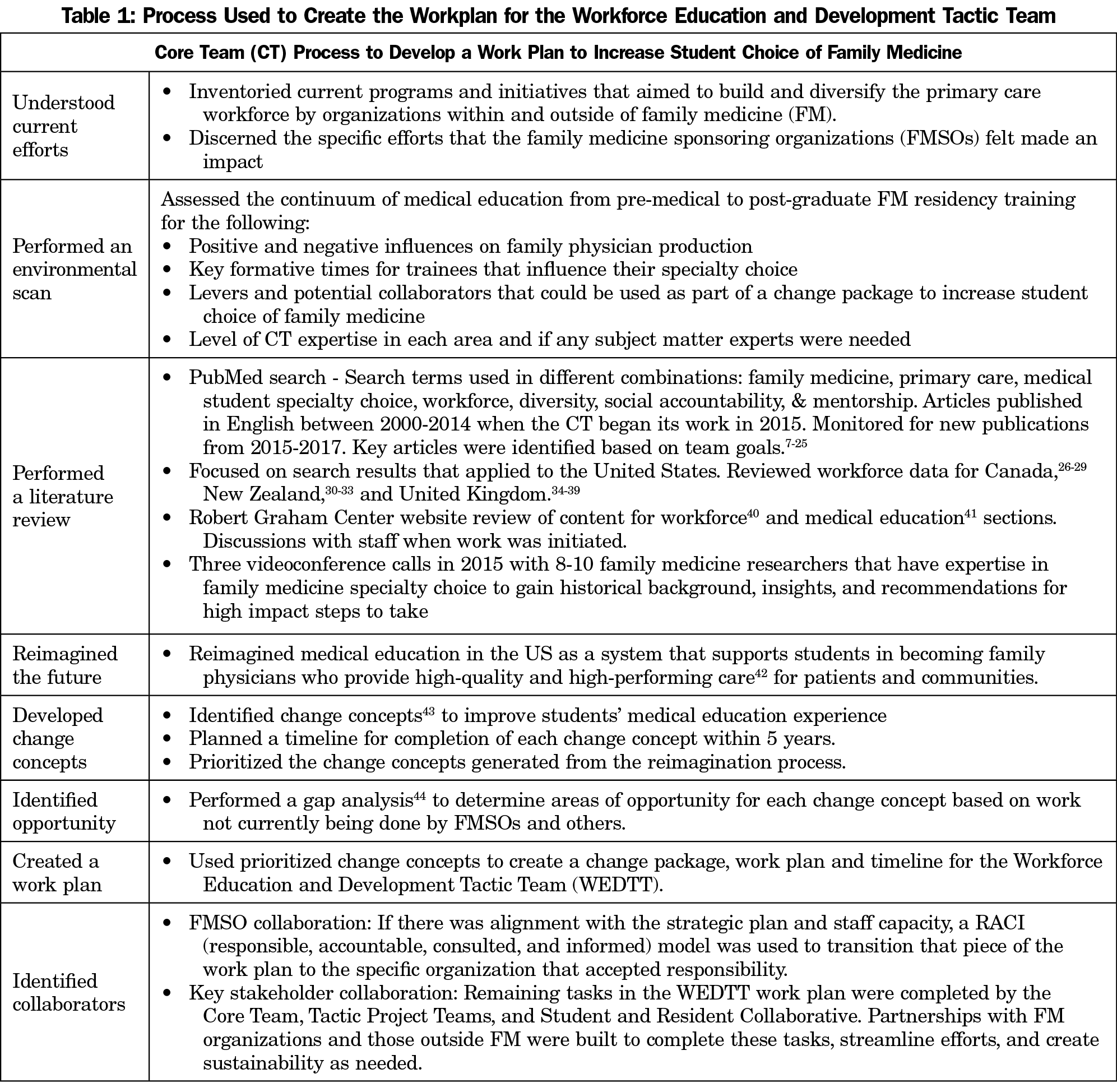

Achieving systemic and cultural change takes time and a shared vision for the future. With the ultimate goal of a physician workforce comprised of 40% primary care in mind,4 the CT proposed the 25 x 2030 as a stretch goal,46 which is a target reached for over a certain time through innovative change. The stretch goal could be supported by an improvement framework that includes milestones, an action plan, a logic model that illustrates how the plan will impact the drivers of change, measurement of outcomes against expected results, and goal adjustment as needed.

To determine a reasonable stretch goal, the CT studied how Canada addressed similar specialty choice challenges, determined how lessons from their success could be applied to the United States, and ascertained a timeframe to achieve it. The number of Canadian medical graduates choosing family medicine as their first choice increased by 52.2% in 9 years—from 23% in 2003 to 35% in 2012 with an overall family medicine fill rate of 40%.27,28

The CT estimated that it would likely take longer for the United States to have a similar gross increase because of the need to influence a greater number of medical schools, shift the undergraduate medical education (UME) system towards social accountability and promotion of family medicine, reform graduate medical education (GME) policy on state and national levels, build collaborations that lead to FM support by other specialties and regulatory bodies, and evaluate the distribution of residency slots across the country by specialty.

The CT further supported the 25 x 2030 goal by looking at workforce data for other countries that declared a need to increase their family physician workforce and achieved success. In New Zealand for example, the number of active general practice (GP) doctors increased by 135% between 2005 and 2016 due to a multipronged effort—Health Workforce New Zealand—that included expansion of medical school training slots and retention efforts.31 And in the United Kingdom, a stretch goal was set in 2015 to generate 5,000 additional GPs in practice by 2020, doubling the rate of growth in primary care in that 5-year period.34-36 As part of a larger initiative to produce and retain a physician workforce that is 50% general practice, GP training slots were expanded in 2016 and filled in 2017 at the highest number ever recruited.35,37

The CT recognizes that there are many challenges to achieving 25 x 2030, including need for payment reform; current capacity and expansion of FM residency programs; faculty recruitment, development, and retention; the potential implications of moving to a single GME accreditation system; and scope of practice issues, among others. To reach 25 x 2030 and overcome these challenges, key stakeholders need to be engaged (Figure 2) and collaboration is essential.

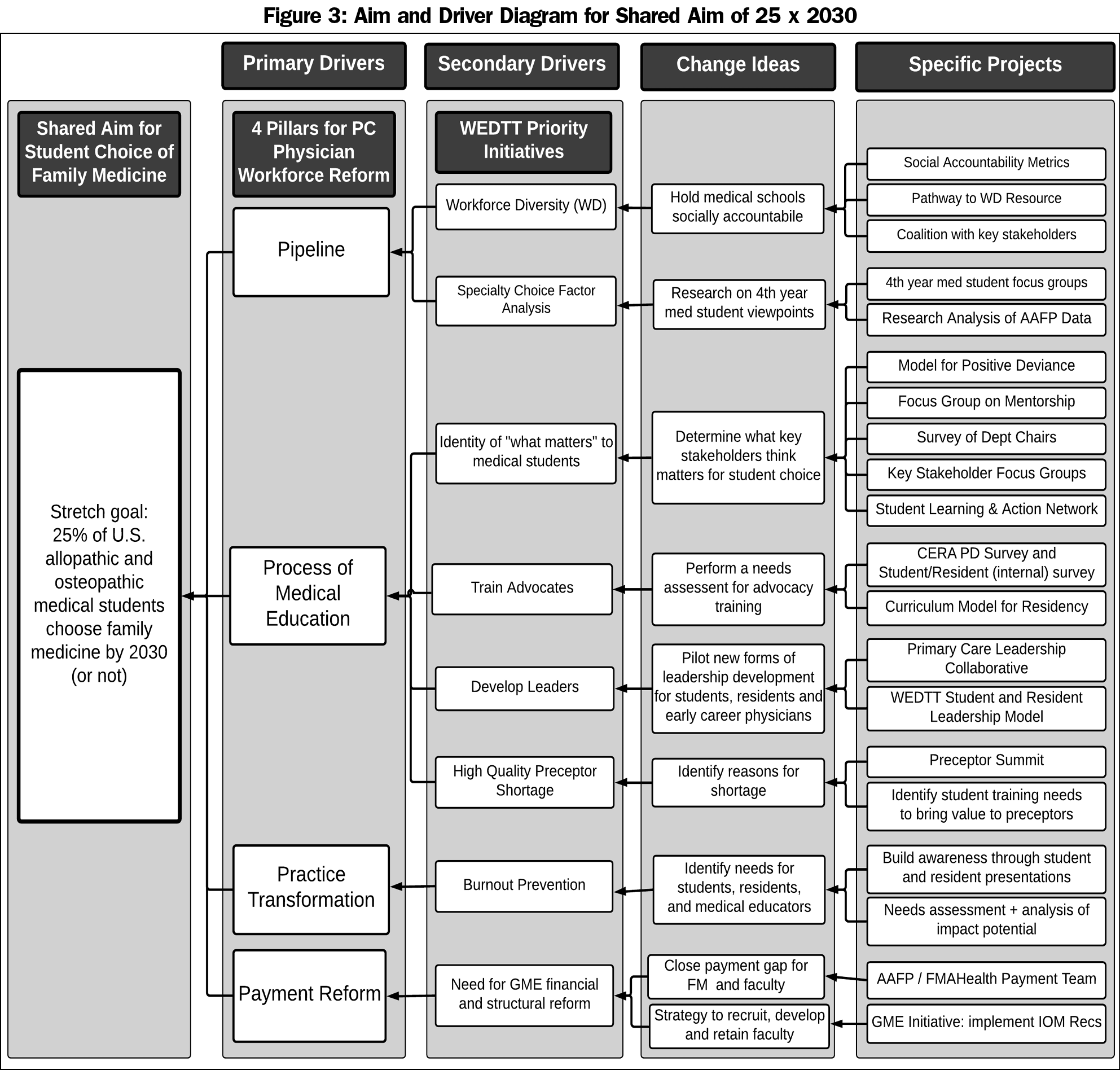

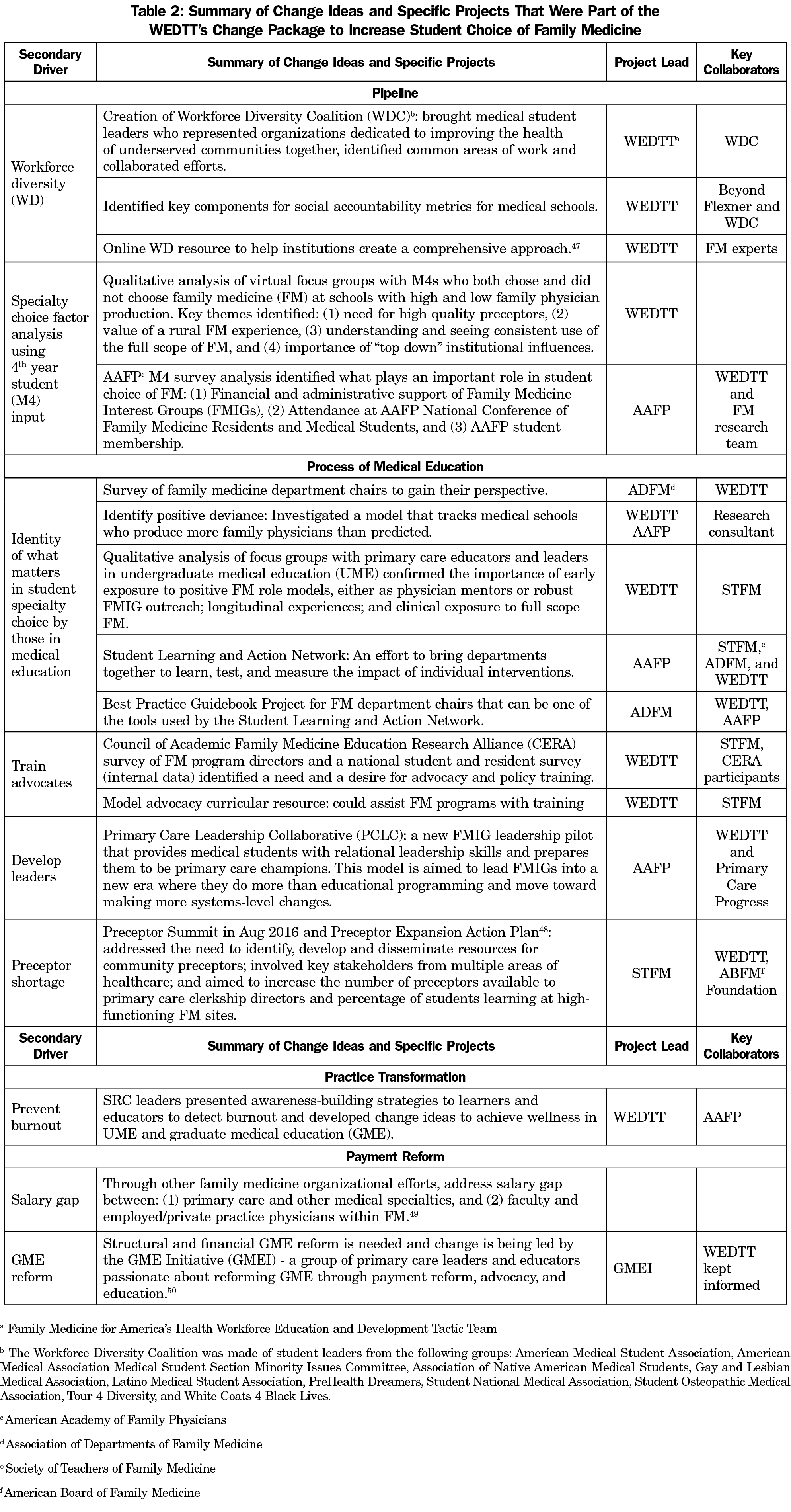

The CT developed a change package based on its theory of what will drive the achievement of 25 x 2030, represented by the aim and driver diagram in Figure 3.43 The four pillars for primary care workforce reform, developed by the Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM),13 were used as the key drivers that influence primary care workforce development, and therefore the foci for interventions to be developed. A set of prioritized secondary drivers led to change ideas and specific projects worked on by the WEDTT, FM organization partners, and key collaborators. Highlights of concepts and specific projects included in the change package are described in Table 2.

The CT’s theory of change, change package, and specific projects that aimed to increase student choice of FM are unique in the following ways: (1) dialogue about 25 x 2030 contributed to the movement from student interest in family medicine to student choice; (2) efforts to build and diversify the family medicine workforce were focused on simultaneously; (3) partnerships with key stakeholders outside of family medicine served as a model for future collaboration.

The responsibility of 25 x 2030 was transitioned to the AAFP in August 2018 during a kickoff event that marked the beginning of a long-term FMSO collaborative to work hand-in-hand to more than double the rate of US medical students choosing family medicine by 2030. Participants of the 2-day meeting included thought leaders and staff of the FMSOs who have a sense of urgency and common purpose.

The meeting agenda utilized a structured effort known as “collective impact” to frame presentations, discussions, and group work.51 This approach is materially different than what has been done in the past to coordinate some efforts across organizations. Collective impact has five conditions: common agenda, shared measurement, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and backbone support.51 Organizations using this approach achieve greater progress than any one isolated organization could accomplish due to the collaborative approach.

Using CAFM’s four pillars for primary care workforce reform13 as the foundation, participants were invited to imagine the possibilities that could be high impact, highly feasible activities to initiate in the context of building on the existing student choice interventions that each FMSO was already engaged in during 2018-2019. Key themes discussed were:

- Impact student experience before medical school. Identify how to support a diverse group that is representative of our communities long before they apply for medical school.

- Impact medical school admissions. Transform it into a holistic system that has specific goals for recruitment and admission of first-generation and underrepresented-in-medicine applicants.

- Impact medical school curriculum and role modeling. Revise the focus of the UME curriculum to one that is patient-centered, community-centered, and primary care-focused and equip enthusiastic FM role models at all levels.

- Impact health system funding and leadership. Enhance FM leadership in medical schools and health systems, foster allyship with patients, and reduce the payment gap between family physicians and subspecialties.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

The FMAHealth Board charged the WEDTT with tactics from the strategic plan that were broad and likely difficult to achieve within the initial 5-year timeline. Since the CT was not part of the initial FMAHealth conversations regarding tactic development, it was challenging to fully understand the background, rationale, and priority level for each tactic. Including the CT in these discussions would have improved the efficiency of developing SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and timely) goals, defined outcomes, and detailed strategies, work plan, timeline, and evaluation for each tactic. Overall, increasing student choice of family medicine was not addressed as well as it could have been due to the WEDTT’s earlier sunset date and the team’s charge to achieve multiple broad tactics.

Because of the decision to accelerate tactic team timelines, the WEDTT had to prioritize tactics and change the charge from three tactics to one tactic that focused on student choice of family medicine. The two remaining tactics were left unfinished, but they are important initiatives that should be addressed through future work.

Questions about responsibility and authority challenges were occasionally posed during the CT discussions and those of other tactic teams. Although CTs were responsible for developing work plans that accomplished the tactics assigned by the FMAHealth Board, the authority, resources, and ability to accomplish this work often needed support from pertinent FMSOs. The FMAHealth Board acting as an interface, while helpful, at times did not provide clarity on what was expected from the FMSO in transitioning the work from CTs back to them. CTs worked closely with pertinent FMSOs because accomplishing the tactic goals required administrative and financial resources not provided by FMAHealth. FMSOs have varied capacities and resources, so responsiveness to requests or transition of work depended on the individual FMSO.

The project management support for the WEDTT consisted of dedicated, hard-working and talented people; however, the capacity to provide support was exceeded by the needs of all seven tactic teams. If similarly structured teams are utilized for the next “future of family medicine” initiatives, the purpose of the teams should be carefully considered. It should be clear whether the purpose is to: (1) generate, develop, and propose new, innovative ideas that are then sent to the FMSOs for consideration, or (2) complete projects themselves based on those ideas. The need for administrative and project management support would depend on the teams’ roles.

- To achieve 25 x 2030, increasing student choice of FM will require moving outside of the influence of family medicine departments and educators and toward a multilayered strategy involving multiple factors, including the social accountability of US medical schools, payment reform, relief of administrative burden, and transformation of practice models.

- To make impactful change, collaboration and clear communication among the family medicine organizations is needed to allow our specialty to speak with one voice and engage key stakeholders inside and outside of family medicine.

- An adaptive approach that centers around and is responsive to the needs and desires of younger generations is paramount to moving the needle on the number of students choosing FM.

- Students, residents, and early-career physicians have an important voice when discussing the future of family medicine. Future initiatives should find unique and sustainable ways to incorporate multiple, diverse voices.

- The plan to achieve 25 x 2030 must prioritize diversity to produce a family medicine workforce as diverse as the US population.

- The full scope of family medicine needs to be preserved. For medical students who choose FM to provide inpatient, maternity, and procedural care that many communities currently lack access to, those must be viable options for them when they graduate from residency and enter practice. Otherwise, family medicine has failed them and the communities they want to serve.

- Identifying new partnerships within and outside of family medicine, including patients, community organizations, patient advocacy groups, and health professional colleagues can help overcome hurdles in medical education redesign, GME reform, and pipeline strategy.

- Future initiatives should focus on creating a diverse group of leaders in order to bring rich discussion, foresee challenges, and agree on solutions most likely to impact change.

- Primary care workforce discussions can easily broaden in scope, which can make it challenging to initiate change. A process that provides a continual checkpoint on whether work is leading toward the shared aim will help reach 25 x 2030.

- Throughout FMAHealth, “family medicine” and “primary care” were terms used interchangeably. This unclear terminology can cause confusion in creating a message for key stakeholders outside of primary care. Although family physicians provide the majority of care within the United States,45 our specialty and leaders must be mindful of the additional health professionals who encompass primary care and the roles of each specialty and profession in provision of this care.

- There are many health professional leaders and organizational staff who are committed and passionate about increasing student choice of family medicine and producing the diverse primary care workforce our nation needs. Their tenacity and hard work were appreciated by the WEDTT during its time, and they are sure to make the shared aim of 25 x 2030 a success.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Support was provided by Family Medicine for America’s Health.

Presentations: Content from this article was presented under various titles at these conferences:

STFM Annual Spring Conference, May 2018, Washington, DC:

- “Primary Care Leadership Collaborative: FMIGs Taking Action to Advance Primary Care”

- “A Need for Formal Advocacy Curricula in Family Medicine”

STFM Conference on Medical Student Education, February 2018, Austin, TX:

- “Characteristics Associated with Advocacy Training in Family Medicine Residency Programs.”

- “Student Choice of Family Medicine: What Impact do FMIGs Have?”

North American Primary Care Research Group, November 2017, Montreal, Canada:

- “Characteristics Associated with Advocacy Training in Family Medicine Residency Programs”

- “Student Choice of Family Medicine: What Impact do FMIGs Have?”

AAFP National Conference, July 2017, Kansas City, MO:

- “Building the Diverse Workforce America Needs”

- “Moving the Needle on Students Choosing Family Medicine: How to Make an Impact”

STFM Annual Spring Conference, May 2017, San Diego, CA:

- “Family Medicine Departments Collaborating to Impact Student Choice”

- “Healing the Healer to Achieve the Quadruple Aim: Reaching Wellness”

- “Student Choice of Family Medicine – What Influence do Family Medicine Interest Groups Have?”

- “Advocacy in Primary Care to Achieve the Triple Aim: What to Do”

AAFP Residency Education Symposium, Residency Program Solutions, March 2017, Kansas City, MO:

- “Physician Advocacy: What Is It and How Do We Train for It?”

- “Student Choice of Family Medicine: What Do Fourth-Year Medical Students Say About It?”

- “How to Incorporate Resident Burnout Prevention into the Residency Curriculum”

STFM Conference on Medical Student Education, February 2017, Anaheim, CA:

- “Family Medicine Interest Groups: What We Know and What We Want to Know”

- “Closing the Leadership Gap in Health Care Through Student and Resident”

- “Development and Involvement: Lessons Learned From Family Medicine for America’s Health”

STFM Conference on Practice Improvement, December 2016, Newport Beach, CA:

- “Producing More Primary Care Physicians to Care for America: How Can We All Better Understand and Help Foster Social Accountability in Our Training Programs and Our Practices?”

AAFP National Conference of Family Medicine Residents and Medical Students, July 2016, Kansas City, MO:

- “Healing the Healer: Achieving Wellness in Medical Education”

- “Family Medicine for America’s Health: Working to Meet the Quadruple Aim and Reduce Health Disparities”

STFM Annual Spring Conference, May 2016, Minneapolis, MN

- “Achieving the Quadruple Aim in Medical Education: Models to Use at Your Institution and for the Future of Family Medicine”

STFM Conference on Medical Student Education, January 2016, Phoenix, AZ:

- “Help Build America’s Workforce and Make Health Primary”

- “Increasing Medical Student Choice of Family Medicine: How Did Canada Do It?”

- Medical Schools that Produce Family Physicians–What Makes the Difference?”

STFM Conference on Practice Improvement: December 2015, Dallas, TX:

- “Partnering to Develop the Family Medicine Workforce We Need”

AAFP National Conference, July 2015, Kansas City, MO:

- “Help Build America’s Family Physician Workforce and Make Health Primary”

References

- Family Medicine for America’s Health. Family Medicine for America’s Health Tactics for the Workforce Education and Development Tactic Team. https://fmahealth.org/workforce-education-development-tactic-team/. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. Family Medicine Entrustable Professional Activities. http://www.afmrd.org/page/epaAccessed October 11, 2018.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

- Council on Graduate Medical Education Twentieth Report, Advancing Primary Care, Dec 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/cogme/Reports/twentiethreport.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Kozakowski S, Travis A, Marcinek J, Bentley A, Fetter G. Results of the 2017 National Resident Matching Program and the American Osteopathic Association Intern/Resident Registration Program: an examination of family medicine and primary care. Fam Med. 2017;49(9):686-692.

- Family Medicine for America’s Health. Student and Resident Leaders on the FMAHealth Workforce Team. https://fmahealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Workforce-Students-Residents.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37(1):111-126. https://doi.org/10.2190/3431-G6T7-37M8-P224

- Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994;344(8930):1129-1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90634-3

- Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970-1998. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):831-865. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.00149

- Grover A, Orlowski JM, Erikson CE. The Nation’s Physician Workforce and Future Challenges. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351(1):11-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2015.10.009

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503-509. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1431

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand, Projections from 2014-2025. AAMC Final Report, Apr 2016.

- Hepworth J, Davis A, Harris A, et al. The four pillars for primary care physician workforce reform: a blueprint for future activity. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(1):83-87. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1608

- Josiah Macy Foundation. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student and resident choices? New York: Josiah Macy Foundation; 2009.

- Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(6):502-512. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502

- Erikson CE, Danish S, Jones KC, Sandberg SF, Carle AC. The role of medical school culture in primary care career choice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1919-1926. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000038

- Jeffe DB, Whelan AJ, Andriole DA. Primary care specialty choices of United States medical graduates, 1997-2006. Acad Med. 2010;85(6):947-958. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dbe77d

- Shipman SA, Jones KC, Erikson CE, Sandberg SF. Exploring the workforce implications of a decade of medical school expansion: variations in medical school growth and changes in student characteristics and career plans. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1904-1912. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000040

- Boelen, Charles, Heck, Jeffery E, World Health Organization. Division of Development of Human Resources for Health. (1995). Defining and measuring the social accountability of medical schools. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/59441 Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Reddy AT, Lazreg SA, Phillips RL Jr, Bazemore AW, Lucan SC. Toward defining and measuring social accountability in graduate medical education: a stakeholder study. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):439-445. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-12-00274.1

- Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, Kolsky G, Spagnola M. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(12):804-811. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00009

- Kruse J. Social accountability across the continuum of medical education: a call for common missions for professional, accreditation, certification, and licensure organizations. Fam Med. 2013;45(3):208-211.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Aligning resources, increasing accountability, and delivering a primary care physician workforce for America. 2014. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/advocacy/workforce/gme/FullGME-090914.pdfAccessed October 11, 2018.

- Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools Dec 2010 http://healthsocialaccountability.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2011/06/11-06-07-GCSA-English-pdf-style.pdf Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Hughes LS, Tuggy M, Pugno PA, et al. Transforming Training to Build the Family Physician Workforce Our Country Needs. Fam Med. 2015;47(8):620-627.

- The College of Family Physicians of Canada. Primary Care and Family Medicine in Canada: A Prescription for Renewal, Position Statement from the College of Family Physicians of Canada, October 2000. https://www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Resources/Resource_Items/Health_Professionals/PRIMARY%20CARE%20AND%20FM%20IN%20CANADA%202000(1).pdf Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS). R-1 Main Residency Match report for the first iteration of entry level postgraduate training positions from 2003-2012. https://www.carms.ca/data-reports/r1-data-reportsAccessed October 11, 2018.

- Canadian Post-MD Education Registry Reports. Individual Specialty Reports. https://caper.ca/en/post-graduate-medical-education/individual-specialty-reports/. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Health Canada. Social Accountability - A Vision for Canadian Medical Schools. White Paper from Health Canada, 2002. https://afmc.ca/pdf/pdf_sa_vision_canadian_medical_schools_en.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Gorman DF, Brooks PM. On solutions to the shortage of doctors in Australia and New Zealand. Med J Aust. 2009;190(3):152-156.

- Medical Council of New Zealand. Workforce Surveys 2001-2016. https://www.mcnz.org.nz/news-and-publications/workforce-statistics/. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Health Workforce New Zealand. The Role of Health Workforce New Zealand https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/role-of-health-workforce-new-zealand-nov14-v2_0.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- New Zealand Ministry of Health. Foundations of Excellence: Building Infrastructure for Medical Education and Training. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/mtb-foundations-of-excellence-aug09.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- National Health Service England and Health Education England. Building the Workforce – The New Deal for General Practice Jan 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/01/building-the-workforce-new-deal-gp.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- National Health Service England. General Practice Forward Review April 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/gpfv.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Health Education England. Report – By Choice Not by Chance. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/By%20choice%20-%20not%20by%20chance.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- National Health Service England, Health Education England. General Practice Forward Review Update April 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/general-practice-forward-view-progress-update-april-2018.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, et al. A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Forum report, third global forum on human resources for health, Recife, Brazil. Geneva: GlobalHealth Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization; 2013, http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/hrhreport2013/. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- OECD. Health Workforce Policies in OECD Countries: Right Jobs, Right Skills, Right Places. Paris, OECD Publishing; 2016. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-workforce-policies-in-oecd-countries_9789264239517-en#page1Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Robert Graham Center. Workforce. https://www.graham-center.org/rgc/publications-reports/browse-by-topic/workforce.html. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Robert Graham Center. Medical Education. https://www.graham-center.org/rgc/publications-reports/browse-by-topic/medical-education.html. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166-171. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1616

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Using Change Concepts for Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Changes/UsingChangeConceptsforImprovement.aspx. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Improvement Toolkit – How to Do a Gap Analysis. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/systems/hospital/qitoolkit/combined/d5_combo_gapanalysis.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Distribution of the U.S. Primary Care Workforce. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/primary/pcwork3/index.html. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Science of Improvement: Tips for Setting Aims http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementTipsforSettingAims.aspx. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Family Medicine for America’s Health. Workforce Diversity Resource. https://fmahealth.org/resources/diversity-resource/Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. STFM Preceptor Expansion Initiative. http://www.stfm.org/Resources/ResourcesforMedicalSchools/PreceptorExpansionInitiative. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Matson C, Davis A, Epling J, et al; rest of the ADFM Education Transformation Committee. Influencing student specialty choice: the 4 pillars for primary care physician workforce development. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(5):494-495. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1859

- The GME Initiative. https://www.gmeinitiative.org/. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Hanleybrown F, Kania J, Kramer M. Channeling Change: Making Collective Impact Work. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/pdf/Channeling_Change_PDF.pdf. Published January, 2012. Accessed October 11, 2018.

There are no comments for this article.