In 2014, Family Medicine for America’s Health (FMAHealth) began implementing a specialty-wide strategic plan. The FMAHealth Board of Directors created an Engagement Tactic Team and charged the team with two major objectives: (1) to engage patients as partners in transforming primary care, and (2) to strengthen working alliances with other primary care professions and key stakeholders to speak with a unified voice for primary care. The team’s first objective sought to engage patients as partners to achieve the triple aim. The second objective required the team to explore how best to collaborate with others to align on core values of high-functioning primary care.

When it comes to realizing the promise of patient-centered care, aspirational strategic objectives are often easier to declare than to implement. As the team grappled with its charge, it discovered that the approach to achieving each objective became as important as the actions required to accomplish them. The team recognized the value of taking ample time to build an approach to delivering patient-centered care that could be sustained and scaled over time to achieve the two objectives.

The team ultimately settled on three projects that leveraged collaborative partnerships with organizations inside and outside the specialty to better understand and advance patient-centered care at three levels: practice transformation, organizational governance, and policy making.

When it comes to improving delivery of patient-centered care and promoting patient engagement, aspirational strategic objectives are often easier to declare than to implement. Indeed, a key lesson learned by many providers—particularly providers of primary care—is the value of taking the time needed to build an approach to delivering patient-centered care that can be sustained and scaled over time.

Early in its formation, the FMAHealth Board recognized the importance of including a patient advocate voice on the board to inform policy decisions. The board thought that a patient advocate would offer knowledge and understanding in at least two dimensions: (1) in engaging patients and patient advocacy organizations, and (2) in representing a wide variety of whole-person patient experiences rather than a singular disease focus. Inclusion of patients’ perspectives through the patient advocate role was a central part of the board’s commitment to learning what it means to be patient-centered and to make decisions accordingly.

In addition to adding a patient representative to the board and in pursuit of obtaining a greater understanding of how best to approach transformation of primary care delivery to promote patient-centeredness, the board also created and charged an Engagement Tactic Team with two primary objectives1:

- To engage patients as partners in transforming primary care practices and the health care system at large in order to enhance the patient experience, improve community health, and reduce costs; and

- To strengthen working alliances with other primary care professions and other stakeholders in order help all speak with a unified voice for primary care.

Achieving one of these objectives alone is an enormous task. Each requires an understanding of the work already taking place in order to build on prior successes and to learn from prior failures. Thus, the team’s first objective sought to engage patients as partners to achieve the triple aim with respect to primary care delivery. The second objective required FMAHealth to explore how best to collaborate with others who have a stake in primary care in ways that create one voice out of a cacophony of interests. In this context, how to approach achieving each objective became as important as the actions required to accomplish them.

The board assembled a diverse team to determine how best to approach the objectives assigned to it, drawing on the policy, organizational, research, and practical knowledge and experience of its team members. The initial team included two practicing family physicians, an academic family physician with expertise in patient engagement, a family physician researcher, a nurse practitioner, a patient advocate, the leader of an organization focused on patient-centered care, and the executive director of a state academy of family physicians.

As the team began its work, its leader and members quickly realized how difficult it would be to achieve the objectives. Should the team focus internally on family medicine community stakeholders or externally? Was the team going to engage frontline family physicians and patients to help their practices become more patient-centered? How could the team make a tangible impact in a relatively short period of time with such ambitious objectives?

Out of these early conversations, a set of criteria emerged by which to determine a concrete focus for the team. The team decided that the projects they selected would need to:

- Be designed to spread in order to achieve national impact over time,

- Offer maximum leverage (ie, a relatively small amount of effort to yield large gains over time),

- Exhibit a consistent and replicable application of a patient-centered framework,

- Lead to measurable outcomes, and

- Contribute to a solid foundation on which others can continue the work after FMAHealth winds down.

The team met monthly for a year, wrestled with the differing perspectives of its members, conducted exploratory research,2-6 and generated several ideas. However, the team ultimately realized that none of the contemplated project ideas met the above criteria.

Forced to start again from the beginning, the team returned to key literature and began to closely consider the patient and family engagement framework laid out by Kristin Carman, et al, in Health Affairs.7

Carman, et al, use the Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM]) definition of patient- and family-centered care:

A partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families (when appropriate) to ensure that decisions respect patients’ wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care.7

Carman and her team further define patient engagement as:

patients, families, their representatives, and health professionals working in active partnership at various levels across the health care system— direct care, organizational design and governance, and policy making—to improve health and health care.7-8

Close assessment of the Carman framework helped to clarify for the team the definition of patient-centered care and the central role that patient engagement plays in designing and delivering patient-centered care. The team agreed with the core premise of the framework: that all three levels of patient engagement are ideally needed to achieve patient-centered care. In short, the framework and its component definitions aligned with how the team wished to pursue achieving its assigned objectives.

As literature reviews established that a great deal of work had already been underway to engage patients at the direct care level (including, but not limited to, shared decision making, patient activation tools, and other strategies) the team decided to devote its focus to the second and third levels of the Carman framework, as referenced above.

The team hypothesized that practices including patients at levels two and three (the organizational design and governance and policy-making levels) would be more difficult to identify because it meant engaging patients as partners in the design and delivery of care. While patient and family advisory councils (PFACs) were spreading widely at the time, they were often, in team members’ experiences, used primarily for obtaining feedback and not for inviting input on how practices should transform the design and delivery of care (eg, changing the ways in which care teams interact with and care for patients and families). Thus, the team refocused its efforts on identifying a small number of projects that (a) aligned with the Carman framework, and (b) met the aforementioned selection criteria.

The Work and Its Outcomes

Using the Carman framework and the selection criteria to screen and select ideas, the team decided to pursue three projects:

- Project #1: Engaging patients as partners systemically in the design and delivery of care. This project emphasized interviewing practices around the country that are currently engaging patients in the design and delivery of care.

- Project #2: Encouraging family medicine organizations to include a patient or public member on their boards of directors. This project focused on partnering with peer family medicine organizations to encourage them to include a patient-centered voice on their boards of directors.

- To promote greater patient engagement at the policy-making level, the team decided to launch Project #3: the development of a set of shared principles of patient-centered, team-based primary care in collaboration with other organizations that have a stake in the discipline.

Project #1: Engaging Patients as Partners Systemically in the Design and Delivery of Care

Project #1

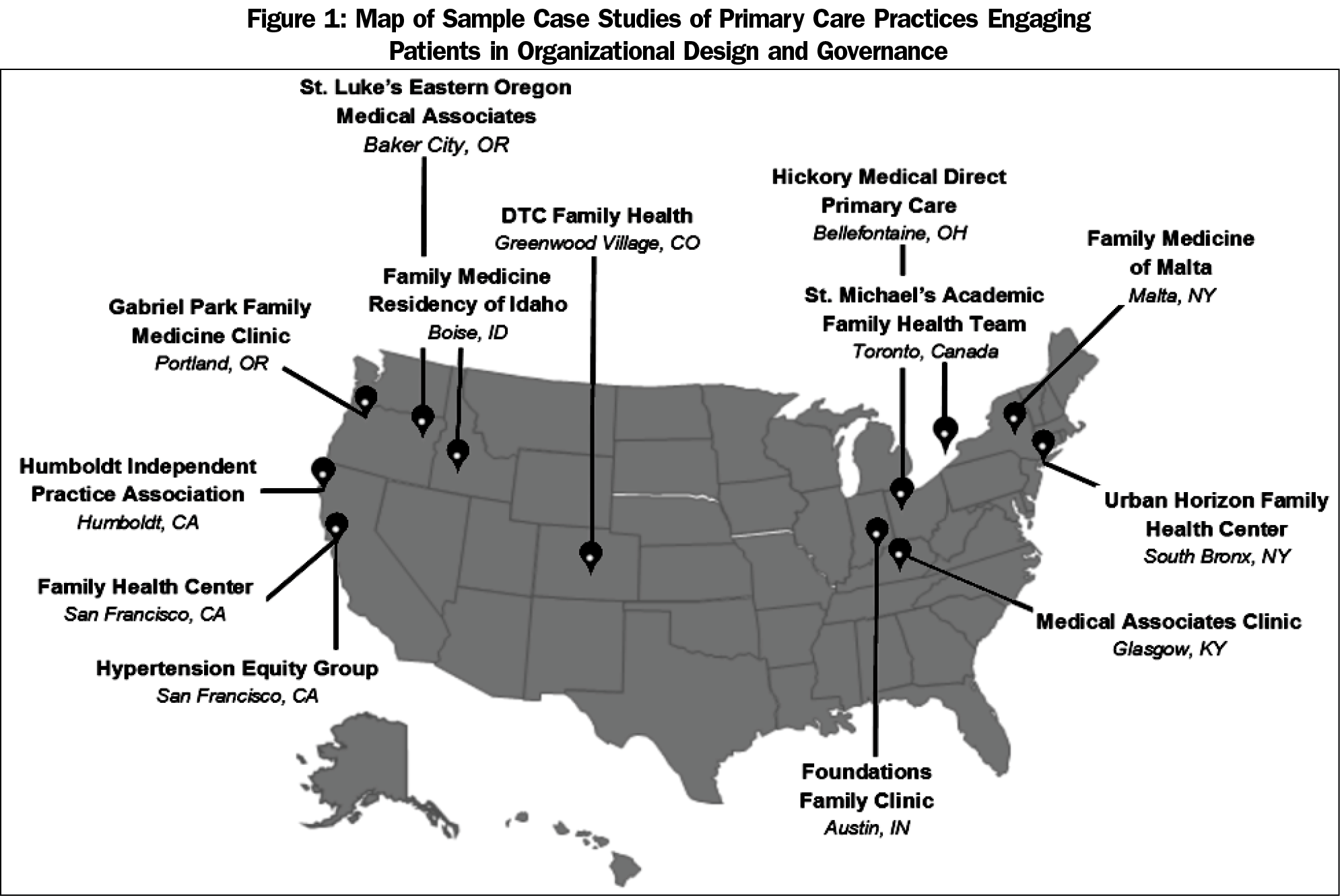

The team, in collaboration with the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Center for Excellence in Primary Care, worked with primary care practices around the country to learn about how they meaningfully engaged patients. After interviewing almost 30 practices, the team identified a dozen that were systemically engaging patients in the design and delivery of care. These practices go beyond asking patients for feedback and invite them to help shape the ways in which teams care for patients, from patient flow to clinician-patient interactions, to codesigning the values and culture of a practice. At the Gabriel Park practice in Portland, Oregon, clinicians and patients work together to decide what the practice culturally aspired to be and the standards that the practice would be accountable to. As Gabriel Park clinicians told the interview team, engaging patients at the front end instead of waiting until later is more efficient and increases the likelihood of implementing patient-oriented initiatives.

At the Urban Horizons Family Health Center in South Bronx, New York, peer educators are empowered to build trust with patients in the community and invite them to participate in patient advisory boards that tackle many important issues. For example, one advisory board worked on a quality improvement project team to address the issue of unrepressed HIV viral load and helped transform the scheduling system from one based on staff availability to one focused on continuity. The same group went on to change the intake process for patients with HIV to decrease stigma and increase confidentiality. Collectively, the case studies reveal that engaging patients is not only a way to improve organizations, but is also a better way to meet the needs of the local community. For more information and additional case studies, see Figure 1 and visit: http://cepc.ucsf.edu/patient-engagement-case-studies.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians (ACOFP), in collaboration with UCSF’s Center for Excellence in Primary Care, will distribute these case studies to share the many practical ideas they contain. Throughout 2019, UCSF will hold webinars and present at conferences to discuss patient engagement and patient-centered care and how to implement the case study strategies.

Project #2: Encouraging Family Medicine Organizations to Include a Patient or Public Member on Their Boards of Directors

As part of the agreement to establish the FMAHealth, LLC, the board was required to appoint a patient or patient advocate member. Including that perspective on the board helped it learn a great deal about what it means to be patient centered in its deliberations and decisions. The board’s experience is consistent with research that demonstrates the value of patient engagement.9-11

The team posited that before it encouraged organizations outside family medicine to include the voice of patients and patient advocates in their governance structures, it first needed to gauge the readiness of the leading family medicine organizations to set an example. The team proposed that each of the eight national family medicine organizations include a patient or a patient advocate on its board—an individual who could effectively bring an unfiltered patient perspective to board deliberations, a perspective not influenced by medical training or deep knowledge of health care systems and delivery.

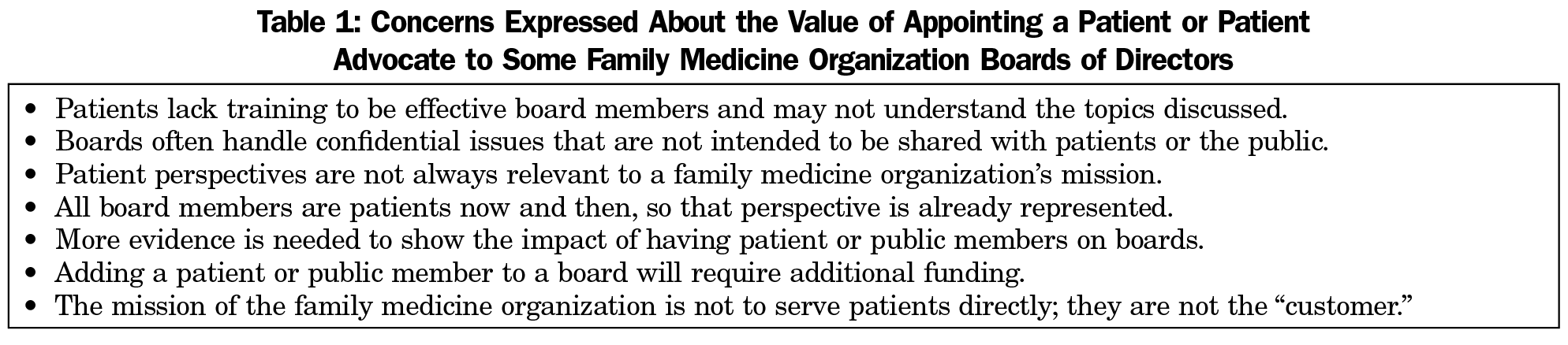

When the team began its work on this project, three family medicine organizations already had at least one patient or patient advocate member on their boards: the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM); the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation; and the North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG). The team’s first task was to learn from their experience. In early 2016, the team introduced a discussion about the value of patients on boards at a biannual gathering of leaders of the eight family medicine organizations. The team discovered a universal commitment to delivering patient-centered care as a policy intent but not necessarily a universal commitment to inviting patients or patient advocates onto their boards of directors simply because some of their peers had elected to do so and found real value in the process. The team and the board learned a great deal from that first discussion and those that followed. Some family medicine organizations expressed hesitancy, and their reasons are detailed in Table 1.

Such concerns are genuine, important to address, and not unique to family medicine. Over the ensuing couple of years, the team met with many of the organizations that expressed initial reservations. Two have developed approaches to test the waters in ways that work for them. The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM), for example, invited team members to its board meeting in 2016 to discuss the value of including a patient or patient advocate on its board. The discussion touched on many of the concerns listed above. The STFM, whose members are primarily those who teach and train future family physicians, determined that it was not ready to appoint such a member to its board. They decided, however, to recruit patients and patient advocates to join STFM committees where they could address issues more directly related to patient-centered care.

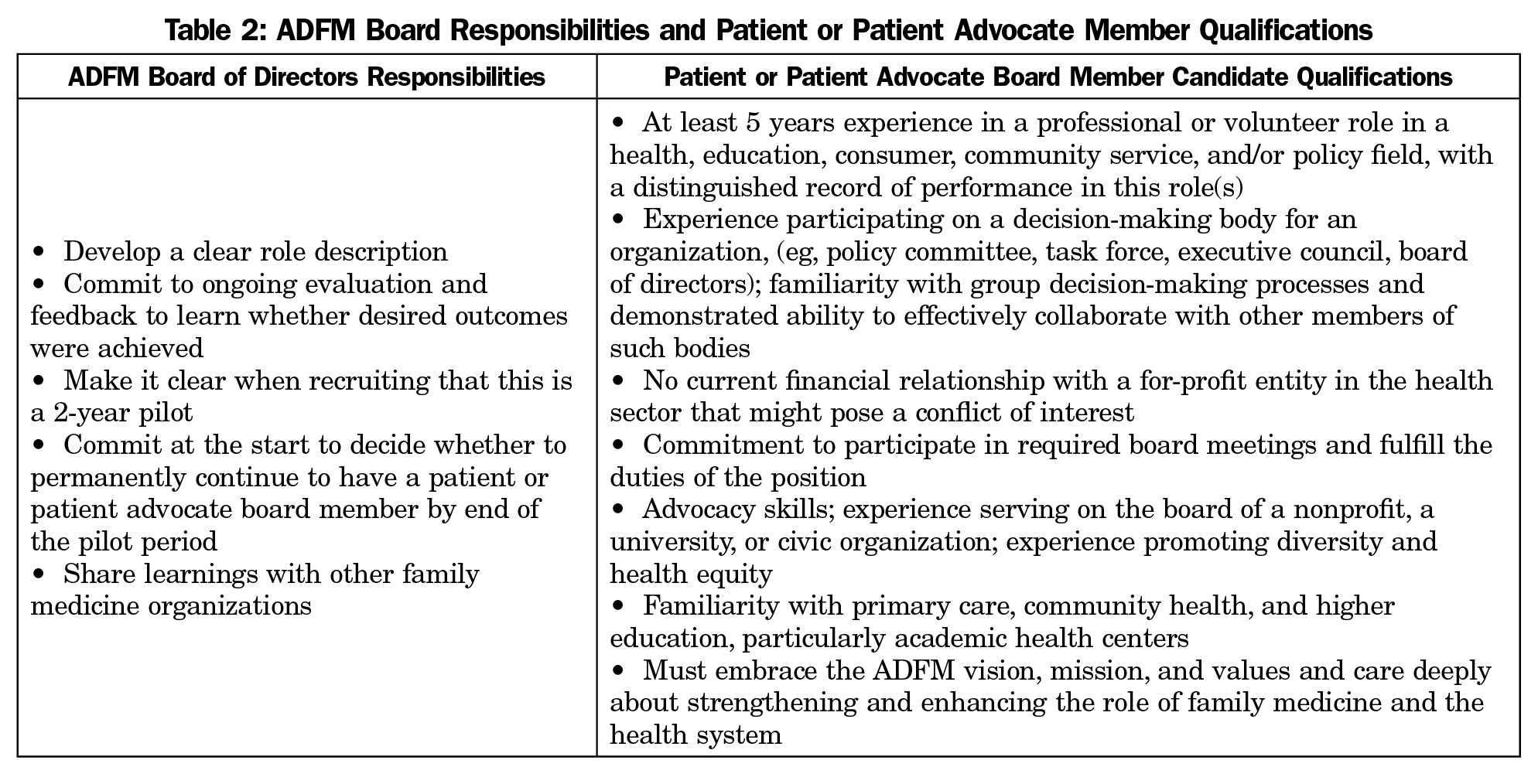

The Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM) had two major concerns about adding a patient or patient advocate member to its board: (1) how to determine the value of patient engagement at the governance level, and (2) how to manage the expense of a new board member over time. ADFM’s board of directors asked the team to help them address both.

Together the team and ADFM created a two-year pilot designed to mitigate their concerns.12 Building upon lessons learned by ABFM and NAPCRG, ADFM worked with the team to outline responsibilities and desired qualifications for a patient or patient advocate member whom ADFM believed could provide the greatest insight. These qualifications helped shape the role and target the recruitment effort. Table 2 outlines the ADFM’s responsibilities and the qualifications of an ideal patient or patient advocate candidate.

After a competitive search process, ADFM appointed its new board member in early 2018. Results of ADFM’s work with its public member, as well as lessons learned, will be shared with peer family medicine organizations to continue to inform their thought process.

Project #3: Developing a Set of Shared Principles of Patient- Centered, Team-Based Primary Care

The specialty of family medicine cannot change primary care policy and practice alone. In collaboration with partners in other clinical disciplines, employers, social service organizations, insurers, and others, major impact in primary care is achievable. Taking a first step in this direction, the team, in collaboration with the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC), formed a multistakeholder steering committee in 2016.13 The team partnered with the PCPCC because the organization counts among its members over 1,000 organizations committed to primary care, including patient advocacy organizations, primary care physician and nursing organizations, behavioral health groups, employers, payers, and others. Collaborating with the PCPCC helped ensure that this effort to create shared principles of patient-centered, team-based primary care would not be solely physician driven.

The committee began by researching previous sets of shared principles, including the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home, the Starfield principles, and those developed by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), the National Partnership for Women and Families, and the World Health Organization (WHO).14-17

Building on that research, the committee worked iteratively, seeking continuous feedback on drafts of the shared principles through public surveys of the aforementioned stakeholder groups. The committee then convened a Shared Principles Summit in December, 2016 in Washington, DC, to review and improve the draft principles. Representatives from over 100 organizations attended, including patients and patient advocates. The result, a set of seven shared principles (Figure 2), has been signed onto and supported by over 300 organizations to date.19

The team decided to engage as many stakeholders as possible to develop the shared principles to lay the foundation on which those with a stake in primary care can align on critical issues facing the field in the future. In November 2018, the board collaborated with the PCPCC to convene the first national workshop of state and national legislators and policy makers, payers, employers, patients, and health care providers to create a 2-year action plan for increasing investment in primary care. The foundation has been laid. It is now up to stakeholders to utilize these shared principles in strategic ways.

Discussion and Conclusion

Key groundwork has been laid to promote meaningful and effective patient engagement at the organizational design and governance and policy-making levels. During this specialty-wide strategic initiative, the FMAHealth board and Engagement Tactic Team accomplished the following:

- The UCSF Center for Excellence in Primary Care led the development of case studies illustrating how practices are systemically engaging patients in the design and delivery of care. These case studies will be disseminated by the American Academy of Family Physicians and American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians. Increasing numbers of practices nationwide are discovering practical ways to engage patients and learning that doing so improves health outcomes and patient satisfaction.

- As of June 2018, four of the eight national family medicine organizations have one or two patient or patient advocate members on their boards of directors, and four do not. The STFM and the ADFM are exploring this idea by engaging public members on various committees and conducting a 2-year public board member pilot, respectively. What the ADFM learns during its pilot will yield insight to inform this ongoing dialogue. For the four organizations without public members on their boards of directors, their concerns are important to acknowledge and continue to address.

- As of October 2018, more than 300 organizations have signed on in support of the shared principles. The PCPCC has made these principles a central part of its strategic plan and is taking a leadership role to increase investment in primary care in as many states as possible over the next 2 years.

To truly advance this work and to sustain and scale patient-centered care and policies, much more time than the duration of FMAHealth is needed. The board and team believe that organizations with a vested interest in primary care should take advantage of the opportunity to learn from practices that are successfully engaging patients and apply those lessons to enhance operations and the patient experience; to continue to explore whether including patient or patient advocate members in governance aligns with organizational mission, vision, and values; and to sign on to the shared principles and utilize them to guide strategic decisions and partnerships. Together, in collaboration with key stakeholders inside and outside of family medicine, we can achieve the two objectives originally envisioned in the FMAHealth strategic plan.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the eight national family medicine organizations for working to ensure that health and health care become truly patient-centered. They also thank those working in practices and state societies who are committed to including patients as partners at the practice, organization, and policy levels. The authors thank the president of the FMAHealth Board, Glen Stream, MD, MBI, and the Engagement Tactic Team chair, Ted Epperly, MD, for their guidance, as well as CFAR, Inc. for its support. Finally, the authors give great thanks to members of the Engagement Tactic Team: Carolyn Gaughan, CAE; Ann Greiner, MA; Kevin Grumbach, MD; Susan Hogeland, CAE; Marci Nielsen, PhD, MPH; Fatema Salam, MPH; Lisa Stewart, MA; Jack Westfall, MD, MPH; Eric Wiser, MD; Diane Stollenwerk, MPP; and Lauren S. Hughes, MD, MPH, MSc.

References

- Family Medicine for America’s Health. About Us. https://fmahealth.org/about-us/. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- American Institutes for Research. Placing Patients at the Center of Health Care. https://www.air.org/resource/placing-patients-center-health-care. Accessed June 10, 2018.

- Healthcare Information and Manaement Systems Society. HIMSS Patient Engagement Framework. https://www.himss.org/himss-patient-engagement-framework. Accessed June 10, 2018..

- James J. Patient engagement. Health Aff. February 14, 2013. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20130214.898775/full/. Accessed November 29, 2018.

- American Institutes for Research. Innovative Patient Engagement Strategies. https://www.air.org/project/innovative-patient-engagement-strategies. Accessed June 10, 2018.

- Athena Health. Patient Engagement Knowledge Hub. https://www.athenahealth.com/knowledge-hub/patient-engagement/framework. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):223-231. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133

- Hurtado M, Swift E, Corrigan J, eds. Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

- Summers L, deLisle K, Ness D, et al. The Impact of Accountable Care: How Accountable Care Impacts the Way Consumers Receive Care. Washington, DC: National Partnership for Women and Families; 2015.

- Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD, Gronseth GS, Gagliardi AR. Impact of patient involvement on clinical practice guideline development: a parallel group study. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0745-6

- Laurance J, Henderson S, Howitt PJ, et al. Patient engagement: four case studies that highlight the potential for improved health outcomes and reduced costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1627-1634. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0375

- Grumbach K, Gilchrist V, Davis A, et al. ADFM and FMAHealth boards’ engagement around a public member pilot study. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(2):182-183. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2212

- The Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. https://www.pcpcc.org. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Starfield B. Primary care: Concept, evaluation, and policy. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1992.

- Epperly T, Roberts R, Rawaf S, et al. Person-centered primary health care: now more than ever. Int J Pers Cent Med. 2015;5(2):53-59.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. The medical home. http://www.aafp.org/practice-management/transformation/pcmh.html. Accessed October 27, 2018.

- National Partnership for Women and Families. Principles for patient- and family-centered care: the medical home from the consumer perspective. http://go.nationalpartnership.org/site/DocServer/Advocate_Toolkit-Consumer_Principles_3-30-09.pdf?docID=4821. Accessed October 27, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Global expert consultation on the WHO framework on patient and family engagement. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/patients_for_patient/news/global-consultation-report.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2018.

- Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Shared Principles of Primary Care. https://www.pcpcc.org/about/shared-principles. Accessed October 31, 2018.

There are no comments for this article.